Soldiers & Colonists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dominion Road Project Overview 2013 05 17.Indd

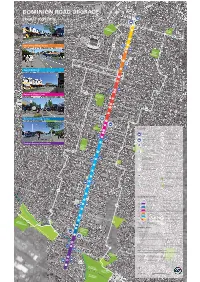

Bond Street DOMINION ROAD UPGRADE PROJECT OVERVIEW VERSION 1 / REVISION 3 ͳ 22ND MAY 2013 Monkey Hill Reserve George Street View Road KOWHAI INTERMEDIATE FICINO Esplanade Road z SCHOOL Onslow Road Lisnoe Avenue Bellevue Road Mt Eden Road Eden Park Walters Road Carrick Place Eden Valley Village Centre Valley Road MOUNT Bellwood Avenue EDEN NORMAL I.T.S Ewington Avenue Burnley Terrace Typical Midblock King Edward Street Prospect Terrace Paice Avenue Grange Road Elizabeth Street Milton Road Saint Albans Avenue KOHIA SCHOOL Balmoral Village Centre BALMORAL Herbert Road SCHOOL Mont Le Grand Road AUCKLAND NORMAL Mount Pleasant Road Brixton Road Dexter Avenue Dunbar Road Balmoral Road Paddinton Green Reserve Mount Roskill Village Center Wiremu street EDENDALE SCHOOL Balmoral Road Balmoral SDA LEGEND Tennyson Street Rocklands Avenue Bus Stops Parallel Cycle Routes Halston Road Carmen Avenue Neighbourhood Bus Cycleway - Greenways Queens Avenue Interchanges Denbigh Avenue Intersection Telford Avenue Dedicated Cycle Lane MAUNGAWHAU New Parking Facili es GOOD SCHOOL SHEPHERD Kensington Avenue SCHOOL Local Area Traffi c Halesowen Avenue I.T.S ITS Parking Trial (May - Management Features Marsden Avenue June) Widened Shared Path Centennial Park Calgary Street Raised Medians and Pedestrian Crossings Mini Round-a-bout Peary Road Wembly Road Pedestrian Controlled Signalised Crossing Lane Realignment Shackleton Road Lambeth Road Signalised Intersec on Right Turn Bay Invermay Avenue Relocate Dairy Sandringham Road Parks Aff ected by Cycleway Hazel Avenue Landscape -

Portrayals of the Moriori People

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. i Portrayals of the Moriori People Historical, Ethnographical, Anthropological and Popular sources, c. 1791- 1989 By Read Wheeler A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History, Massey University, 2016 ii Abstract Michael King’s 1989 book, Moriori: A People Rediscovered, still stands as the definitive work on the Moriori, the Native people of the Chatham Islands. King wrote, ‘Nobody in New Zealand – and few elsewhere in the world- has been subjected to group slander as intense and as damaging as that heaped upon the Moriori.’ Since its publication, historians have denigrated earlier works dealing with the Moriori, arguing that the way in which they portrayed Moriori was almost entirely unfavourable. This thesis tests this conclusion. It explores the perspectives of European visitors to the Chatham Islands from 1791 to 1989, when King published Moriori. It does this through an examination of newspapers, Native Land Court minutes, and the writings of missionaries, settlers, and ethnographers. The thesis asks whether or not historians have been selective in their approach to the sources, or if, perhaps, they have ignored the intricacies that may have informed the views of early observers. The thesis argues that during the nineteenth century both Maori and European perspectives influenced the way in which Moriori were portrayed in European narrative. -

Te Awamutu Courier

Te Awamutu Ph (07) 871-5069 email: [email protected] Your community newspaper for over 100 years Thursday, August 8, 2019 410 Bond Road, Te Awamutu C A/H 021 503 404 Rocking out Agencies on move at Bandquest The Waikato round of this year’s Rockshop Bandquest is in Hamilton on Monday, August 12. Young bands from the region will take to the stage at Clarence St Theatre from 6.30pm. Among the bands performing are Te Awamutu Intermediate bands Waxy Thursday and 6 minute noodle and Te Pahu¯School bands Freeze Point and Five Savages. They will be among 200 intermediate and primary school bands taking part in the competition in towns from Auckland to Dunedin. Get support The next La Leche League breastfeeding support meeting is on Wednesday, August 14 at the Kindergarten Room, Presbyterian Church, Mutu Street from 10am to midday. Meetings are held every second Wednesday of the month. Zone scheme Te Awamutu Intermediate is planning to implement an enrolment zone scheme for 2020, due to growth in the Blank canvas at 204 Sloane St that will be a dual home for Government agencies Work and Income and Oranga Tamariki. Photo / Dean Taylor district. The community is invited to a consultation meeting on Landmark building demolished to make room for site Wednesday, August 14 in the library/hub. There are also forms BY DEAN TAYLOR building has been demolished begin preparations for the co- available at the school office. and the site cleared for the new location.” A landmark building in facility. The new site will Oranga Tamariki — Ministry -

ROBERT a Mcclean R

ROBERT A McCLEAN R. A. McClean Matakana Island Sewerage Outfall Report VOLUMES ONE AND TWO: MAIN REPORT AND APPENDIX Wai 228/215 January 1998 Robert A McClean Any conclusions drawn or opinions expressed are those of the author. Waitangi Tribunal Research 2 R. A. McClean Matakana Island Sewerage Outfall Report THE AUTHOR My name is Robert McClean. I was born in Wellington and educated at Viard College, Porirua. After spending five years in the Plumbing industry, I attended Massey University between 1991 and 1996. I graduated with a Bachelor in Resource and Environmental Planning with first class honours and a MPhil in historical Geography with distinction. My thesis explored the cartographic history of the Porirua reserve lands. Between 1995 and 1997, I completed a report for the Porirua City Council concerning the the management. of Maori historical sites in the Porirua district. I began working for the Waitangi Tribunal in May 1997 as a research officer and I have produced a report concerning foreshores and reclamations within Te Whanganui-a Tara (Wellington Harbour, Wai 145). I am married to Kathrin and we have four children; Antonia, Mattea, Josef and Stefan. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to all those persons who have helped me research this claim. Especially Dr Johanna Rosier (Massey University), Andy Bruere, Rachel Dadson, Betty Martin (Environment B.O.P), Graeme Jelly, Alison McNabb (Western Bay of Plenty District Council), Bob Drey (MAF), David Phizacklea (DOC), Erica Rolleston (Secretary of Tauranga Moana District Maori Council), Christine Taiawa Kuka, Hauata Palmer (Matakana Island), Rachael Willan, Anita Miles and Morrie Love (Waitangi Tribunal). -

New Zealand Wars Sources at the Hocken Collections Part 2 – 1860S and 1870S

Reference Guide New Zealand Wars Sources at the Hocken Collections Part 2 – 1860s and 1870s Henry Jame Warre. Camp at Poutoko (1863). Watercolour on paper: 254 x 353mm. Accession no.: 8,610. Hocken Collections/Te Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago Library Nau Mai Haere Mai ki Te Uare Taoka o Hākena: Welcome to the Hocken Collections He mihi nui tēnei ki a koutou kā uri o kā hau e whā arā, kā mātāwaka o te motu, o te ao whānui hoki. Nau mai, haere mai ki te taumata. As you arrive We seek to preserve all the taoka we hold for future generations. So that all taoka are properly protected, we ask that you: place your bags (including computer bags and sleeves) in the lockers provided leave all food and drink including water bottles in the lockers (we have a researcher lounge off the foyer which everyone is welcome to use) bring any materials you need for research and some ID in with you sign the Readers’ Register each day enquire at the reference desk first if you wish to take digital photographs Beginning your research This guide gives examples of the types of material relating to the New Zealand Wars in the 1860s and 1870s held at the Hocken. All items must be used within the library. As the collection is large and constantly growing not every item is listed here, but you can search for other material on our Online Public Access Catalogues: for books, theses, journals, magazines, newspapers, maps, and audiovisual material, use Library Search|Ketu. -

The New Zealand Wars: 19Th Century Views and Accounts

W E L C O M E T O T H E H O C K E N 50c Friends of the Hocken Collections B U L L E T I N N U M B E R 12 : June 1995 The New Zealand Wars: 19th Century Views and Accounts HIS listing notes only those writings which reflect 19th century views and accounts of the New Zealand wars. Only a few, therefore, are dated post-1900, and these are reprints of 19th Tcentury manuscripts. During the Victorian era the wars in this country were named both the New Zealand Wars and the Maori Wars. There was not universal agreement among pakehas that the Maoris were in the wrong, and a small number of writers, often clergymen, took the side of the latter. While books and pamphlets held in the Hocken are easily traced through the Library’s card and on-line catalogues, or by reference to the New Zealand National Bibliography, despatches in the N.Z. Government Gazette and articles in newspapers and periodicals held in the Hocken are generally unlisted in these sources. ABBREVIATIONS: AWN = Auckland Weekly News; MR = Monthly Review (Wellington); NZE = N.Z. Examiner (London); NZG = N.Z. Gazette; NZH = N.Z. Herald; OW = Otago Witness. [Aborigines Protection Soc.] The New-Zealand Macmillan’s Magazine, vol.20, 1869: p.417-424. Government and the Maori war of 1863–64 …, Photocopy. London, William Tweedie ptr, 1864. Brown, Albert J. ‘Saved as by Fire. An Adventure of — The New Zealand War of 1860; an Inquiry into Its the Maori War’, AWN, 19 May 1899: p.40. -

THE UNIVERSITY Heritage Trail

THE UNIVERSITY Heritage Trail Established by The University of Auckland Business School www.business.auckland.ac.nz ARCHITECTURAL AND HISTORIC ATTRACTIONS The University of Auckland Business School is proud to establish the University Heritage Trail through the Business History Project as our gift to the City of Auckland in 2005, our Centenary year. In line with our mission to be recognised as one of Asia-Pacific’s foremost research-led business schools, known for excellence and innovation in research, we support the aims of the Business History Project to identify, capture and celebrate the stories of key contributors to New Zealand and Auckland’s economy. The Business History Project aims to discover the history of Auckland’s entrepreneurs, traders, merchants, visionaries and industrialists who have left a legacy of inspiring stories and memorable landmarks. Their ideas, enthusiasm and determination have helped to build our nation’s economy and encourage talent for enterprise. The University of Auckland Business School believes it is time to comprehensively present the remarkable journey that has seen our city grow from a collection of small villages to the country’s commercial powerhouse. Capturing the history of the people and buildings of our own University through The University Heritage Trail will enable us to begin to understand the rich history at the doorstep of The University of Auckland. Special thanks to our Business History project sponsors: The David Levene Charitable Trust DB Breweries Limited Barfoot and Thompson And -

Immigration During the Crown Colony Period, 1840-1852

1 2: Immigration during the Crown Colony period, 1840-1852 Context In 1840 New Zealand became, formally, a part of the British Empire. The small and irregular inflow of British immigrants from the Australian Colonies – the ‘Old New Zealanders’ of the mission stations, whaling stations, timber depots, trader settlements, and small pastoral and agricultural outposts, mostly scattered along the coasts - abruptly gave way to the first of a number of waves of immigrants which flowed in from 1840.1 At least three streams arrived during the period 1840-1852, although ‘Old New Zealanders’ continued to arrive in small numbers during the 1840s. The first consisted of the government officials, merchants, pastoralists, and other independent arrivals, the second of the ‘colonists’ (or land purchasers) and the ‘emigrants’ (or assisted arrivals) of the New Zealand Company and its affiliates, and the third of the imperial soldiers (and some sailors) who began arriving in 1845. New Zealand’s European population grew rapidly, marked by the establishment of urban communities, the colonial capital of Auckland (1840), and the Company settlements of Wellington (1840), Petre (Wanganui, 1840), New Plymouth (1841), Nelson (1842), Otago (1848), and Canterbury (1850). Into Auckland flowed most of the independent and military streams, and into the company settlements those arriving directly from the United Kingdom. Thus A.S.Thomson observed that ‘The northern [Auckland] settlers were chiefly derived from Australia; those in the south from Great Britain. The former,’ he added, ‘were distinguished for colonial wisdom; the latter for education and good home connections …’2 Annexation occurred at a time when emigration from the United Kingdom was rising. -

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola. "South - the Endurance of the Old, the Shock of the New." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 60-75. Roger, W. "Six Months in Another Town." Auckland Metro 40 (1984): 155-70. ———. "West - in Struggle Country, Battlers Still Triumph." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 88-99. Young, C. "Newmarket." Auckland Metro 38 (1984): 118-27. 1 General works (21) "Auckland in the 80s." Metro 100 (1989): 106-211. "City of the Commonwealth: Auckland." New Commonwealth 46 (1968): 117-19. "In Suburbia: Objectively Speaking - and Subjectively - the Best Suburbs in Auckland - the Verdict." Metro 81 (1988): 60-75. "Joshua Thorp's Impressions of the Town of Auckland in 1857." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 35 (1979): 1-8. "Photogeography: The Growth of a City: Auckland 1840-1950." New Zealand Geographer 6, no. 2 (1950): 190-97. "What’s Really Going On." Metro 79 (1988): 61-95. Armstrong, Richard Warwick. "Auckland in 1896: An Urban Geography." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1958. Elphick, J. "Culture in a Colonial Setting: Auckland in the Early 1870s." New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 10 (1974): 1-14. Elphick, Judith Mary. "Auckland, 1870-74: A Social Portrait." M.A. thesis (History), University of Auckland, 1974. Fowlds, George M. "Historical Oddments." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 4 (1964): 35. Halstead, E.H. "Greater Auckland." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1934. Le Roy, A.E. "A Little Boy's Memory of Auckland, 1895 to Early 1900." Auckland-Waikato Historical Journal 51 (1987): 1-6. Morton, Harry. -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

(Open Agenda) 06.05.19 Council Room – Level 2 Clocktower, Princes Street 22, Auckland 4:00Pm Page

COUNCIL PART A OPEN AGENDA 06.05.19 - COUNCIL, 06.05.19 AGENDA PART A Council Agenda Part A (Open Agenda) 06.05.19 Council Room – Level 2 ClockTower, Princes Street 22, Auckland 4:00pm Page # The Chancellor moves that the apologies, if any, be noted. 1. APOLOGIES The Chancellor welcomes Ms Rachael Newsome to 2. WELCOME her first meeting as member of Council. The Chancellor moves that the disclosures, if any, be noted 3. DISCLOSURES OF The attention of Members is drawn to the Conflicts of and the action taken be endorsed. INTEREST BY Interest Policy and the need to disclose any interest MEMBERS in an item on the Agenda of the meeting as set out in s175 of the Education Act 1989. 8 4. COUNCIL MEETINGS 4.1 Council, Draft Minutes (Part A), 11.03.19 The Chancellor moves that the Minutes (Part A), 11.03.19 be taken as read and confirmed. 4.2 Matters arising from the Minutes (Part A), 11.03.19 not elsewhere on the Agenda 5. VICE-CHANCELLOR’S 15 The Chancellor moves that the Vice-Chancellor’s Report be REPORT noted. 6. REPORTS OF COUNCIL 6.1 CAPITAL EXPENDITURE COMMITTEE The Chancellor moves that the Capital Expenditure COMMITTEES Committee Minutes (Part A), 04.04.19 be received. 93 6.1.1 Minutes (Part A), 04.04.19 Council Agenda 06.05.19 Page 1 of 8 2 COUNCIL PART A OPEN AGENDA 06.05.19 - COUNCIL, 06.05.19 AGENDA PART A The Chancellor moves that the recommendations in Part A 95 7. -

Transactions Discovery Lodge of Research

Transactions of the Discovery Lodge of Research No. 971, United Grand Lodge of New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory direct descendant of the Research Lodge of New South Wales and the Sydney Lodge of Research The lodge generally meets in the Sydney Masonic Centre on the first Thursday of alternate months March (Installation), May, July, September & November, at 7 pm. Dress: lounge suit, lodge tie, regalia. Master WBro Ewart Stronach Secretary VWBro Neil Wynes Morse, KL PO Box 7077, Farrer, ACT 2607 ph. H (+61) (2) 6286 3482, M 0438 288 997 email: [email protected] website: http://www.discoverylodge.org/ Foundation member of the Australian & New Zealand Masonic Research Council website: http://anzmrc.org/ Volume 4 Number 1 March 2012 How the medieval way of life affected our Masonic rituals 20 September 2011 by RWBro Rodney Grosskopff, KL (South Africa) Religion Religion played an enormous part in the life of medieval society; however, it had none of the freedom we enjoy today. There was one established Church and you belonged to it, or died. It was as simple as that. Heresy Heretics were not tolerated; they were put to death in the most painful ways. That great sixteenth-century intellectual, Sir Thomas More, put the matter very clearly. He believed that heretics should be burned alive, that ‘Princes should punish them according to justice, by a most painful death’, both as a punishment for heresy and as a deterrent to others.1 In England, being burnt alive at the stake was considered a sufficient punishment for a heretic.2 Later Henry VIII thought being hung, drawn and quartered was more appropriate.