Tango Levels: the 22 Techniques of Tango

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventario De Seis Milongas De Buenos Aires: Experiencia Piloto De Participación Comunitaria Índice

INVENTARIO DE SEIS MILONGAS DE BUENOS AIRES: EXPERIENCIA PILOTO DE PARTICIPACIÓN COMUNITARIA ÍNDICE Prólogo 4 Introducción 6 Presentación 12 Asociación de Fomento Mariano Acosta (“La Tierrita”) 38 1. Presentación 39 2. Espacio 39 3. Elemento “Códigos sociales de pista” 40 4. Comunidad 43 5. Salvaguardia y transmisión 45 Club Atlético Milonguero (Huracán) 46 1. Presentación 47 2. Espacio 48 3. Elemento “Códigos sociales de pista” 48 4. Comunidad 51 5. Salvaguardia y transmisión 54 La Milonguita 55 1. Presentación 56 2. Espacio 57 3. Elemento “Códigos sociales de pista” 58 4. Comunidad 63 5. Salvaguardia y transmisión 66 Lo de Celia 67 1. Presentación 68 2. Espacio 69 3. Elemento “Códigos sociales de pista” 70 4. Comunidad 74 5. Salvaguardia y transmisión 75 Sin Rumbo 76 1. Presentación 77 2. Espacio 77 3. Elemento “Códigos sociales de pista” 79 4. Comunidad 81 5. Salvaguardia y transmisión 83 Sunderland Club (Milonga Malena) 84 1. Presentación 85 2. Espacio 86 3. Elemento “Códigos sociales de pista” 86 4. Comunidad 91 5. Salvaguardia y transmisión 93 Síntesis sobre las milongas inventariadas 94 Conclusiones 96 PRÓLOGO El ritmo extremadamente rápido con que se ha venido ratificando en el mundo entero la Convención para la Salvaguardia del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial (PCI) es un testimonio de la preocupación de la comunidad in- ternacional por el tema, especialmente en un momento de rápida transfor- mación social y globalización, donde el patrimonio vivo se enfrenta a graves riesgos de deterioro, desaparición y destrucción. Consciente de la necesidad de brindar herramientas a los Estados y en res- puesta a un contexto global que día a día presenta nuevos retos, la UNESCO ha puesto en marcha una estrategia global con vistas al fortalecimiento de las capacidades nacionales para la salvaguardia del PCI. -

The Jewish Influence on Tango”

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont 2014 Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Research Award Research Award 5-8-2014 The ewJ ish Influence on Tango Olivia Jane Zalesin Pomona College Recommended Citation Zalesin, Olivia Jane, "The eJ wish Influence on Tango" (2014). 2014 Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Research Award. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cclura_2014/2 This First-Year Award Winner is brought to you for free and open access by the Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Research Award at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2014 Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Research Award by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2014 Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Research Award First-Year Award Winner Olivia Zalesin Pomona College Reflective Essay Undergraduate Research Award Reflective Essay “Jewish Tango.” Seems like an odd yet intriguing combination of words--does it not? That’s what I thought back in September as I sat in my dorm room brainstorming potential paper topics for my ID1 Seminar, “Tripping the Light Fantastic: A History of Social and Ballroom Dance.” Tango was an obvious choice to respond to a prompt, which read, “Write about any dance form you find interesting.” I’d been fascinated with the tango ever since I’d learned about the dance’s history in a high-school seminar on Modern Latin America and subsequently tried the dance myself in one of Buenos Aires’ famous dance halls. The Jewish element was, however, my attempt to add some personal element and to answer my own curiosity about a question that had been nagging at me ever since I heard my first tango music. -

The Queer Tango Book Ideas, Images and Inspiration in the 21St Century

1 Colophon and Copyright Statement Selection and editorial matter © 2015 Birthe Havmoeller, Ray Batchelor and Olaya Aramo Written materials © 2015 the individual authors All images and artworks © 2015 the individual artists and photographers. This publication is protected by copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private research, criticism or reviews, no part of this text may be reproduced, decompiled, stored in or introduced into any website, or online information storage, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without written permission by the publisher. This publication is Free and Non Commercial. When you download this e-book, you have been granted the non-exclusive right to access and read the book using any kind of e-book reader software and hardware or via personal text-to-speech computer systems. You may also share/distribute it for free as long as you give appropriate credit to the editors and do not modify the book. You may not use the materials of this book for commercial purposes. If you remix, transform, or build upon the materials you may NOT distribute the modified material without permission by the individual copyright holders. ISBN 978-87-998024-0-1 (HTML) ISBN 978-87-998024-1-8 (PDF) Published: 2015 by Birthe Havmoeller / Queertangobook.org E-book and cover design © Birthe Havmoeller Text on the cover is designed with 'MISO', a free font made by Mårten Nettelbladt. 2 The Queer Tango Book Ideas, Images and Inspiration in the 21st Century Edited by Birthe Havmoeller, Ray Batchelor and Olaya Aramo In the memory of Ekatarina 'Kot' Khomenko We dedicate this work to the dancers who came before us and to those who will come after. -

Spring Summer Autumn Winter This Guide Is a Publication of Modern Tango World Magazine It Is Part of a Series of Publica- Tions Proguced by the Magazine

Wodern Tango World Festival Guide 2016 Spring Summer Autumn Winter This guide is a publication of Modern Tango World magazine It is part of a series of publica- tions proguced by the magazine. Printed copies are available for 20€ on the the magazines website - http://www.moderntangoworld.com Modern Tango World also maintains several Facebook groups. Among them are : Modern Tango World https://www.facebook.com/groups/moderntangoworld/ Modern Tango Dance — This group specializes in examples of modern tango dancing. The group promotes and distributes information about danc- ing to 21st Century tango music. https://www.facebook.com/groups/milonguerrillas/ Modern Tango Fashion — This group specializes in modern tango fashion, the dresses, the trousers, the jewelry and of course, the shoes from mod- ern designers around the world. https://www.facebook.com/groups/moderntangofashion/ Modern Tango Art & Photography — This group specializes in visual arts related to the modern tango, and presents the work of painters, sculptors, illustrators and photographers. https://www.facebook.com/groups/1652601954955310/ Modern Tango Motion Pictures & Books — This group specializes in literary and storytelling about modern tango. Both new and old films and books are presented for review. https://www.facebook.com/groups/889051234488857/ Spring Argentina Leyendas Tango Festival Buenos Aires Myrna Gil Quintero https://www.facebook.com/Leyendas-Tango-Festival-Tango-y-Cultura-Argenti- na-273989612764210/ Festival de Tango de Zárate Buenos Aires https://www.facebook.com/festivalzarate -

Tango DJ 101 Presentation

Tango DJ 101 "A Long Dark Night in Dabney Hall" guided by Homer G Ladas Through a reality based situation we will explore the good, better, not so good, and worst ways to tango DJ. Let Us Begin: ------------------------------ You are the guest DJ tonight at Dabney Hall! The milonga is about to start (class is ending) and you just arrived... As a 'mental DJ exercise' before set-up: While the teachers are wrapping up, you hear from a trusted source that they played only late 50's Carlos Di Sarli instrumentals for the entire class. What music do you start the evening with? A. Juan D'Arienzo early Instr &/or w/ Echague B. Carlos Di Sarli - instrumentals C. Tango Fusion - alternative set D. a Milonga or Vals tanda E. Edgardo Donato (mixed 30's & 40's) w/ lyrics F. Juan D'Arienzo with Maure You have about 3 minutes to decide... Time Out: Let's Briefly Talk DJ Equipment 1. Laptop(s), iPhone, etc, vs. CD's - What equipment to use? 2. Sound Cards & Cleaning Software - Do they make a difference? 3. Headphones (& thus previewing) - Does this help your DJing or not? 4. Any other questions? Tango DJ 101: Tandas What is a Tanda? Why do we use Tandas? (Listen to Examples) How Many Songs (2, 3, 4)? A-List vs B-List Songs? Power Songs - The What, Why, and When! & Jinx Songs... Exercise: Let's build two tanda's together... A. Traditional B. Alternative Back to Reality: The Initial Set-Up Some Questions to Ask Yourself include... 1. - Do you know your sound-system & environment? (amp quality, room/speaker layout & height rule, etc) 2. -

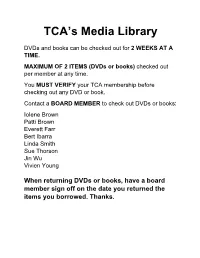

TCA's Media Library

TCA’s Media Library DVDs and books can be checked out for 2 WEEKS AT A TIME. MAXIMUM OF 2 ITEMS (DVDs or books) checked out per member at any time. You MUST VERIFY your TCA membership before checking out any DVD or book. Contact a BOARD MEMBER to check out DVDs or books: Iolene Brown Patti Brown Everett Farr Bert Ibarra Linda Smith Sue Thorson Jin Wu Vivien Young When returning DVDs or books, have a board member sign off on the date you returned the items you borrowed. Thanks. Tango Club of Albuquerque Video Rentals – Complete List V1 - El Tango Argentino - Vol 1 Eduardo and Gloria A famous dancing and teaching couple have developed a series of tapes designed to take a dancer from neophyte to accomplished intermediate in salon-style Tango. (This is not the club-style Tango Eduardo sometimes teaches in workshops.) The first tape covers the basics including the proper embrace and elementary steps. The video quality is high and so is the instruction. The voice over is a bit dramatic and sometimes slightly out of synch with the steps. The tapes are a somewhat expensive for the amount of material covered, but this is a good series for anyone just starting in Tango. V2 - El Tango Argentino - Vol 2 Eduardo and Gloria A famous dancing and teaching couple have developed a series of tapes designed to take a dancer from neophyte to accomplished intermediate in salon-style Tango. (This is not the club-style Tango Eduardo sometimes teaches in workshops.) The second and third videos cover additional steps including complex figures and embellishments. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Social Tango Dancing in the Age of Neoliberal Competition Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6fc7h18z Author Shafie, Radman Publication Date 2019 License CC BY 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Social Tango Dancing in the Age of Neoliberal Competition A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Radman Shafie June 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Anthea Kraut, Chairperson Dr. Marta Savigliano Dr. Jose Reynoso i Copyright by Radman Shafie 2019 ii The Dissertation of Radman Shafie is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside iii Acknowledgments I have deep gratitude for all the people who made this research possible. I would like to first thank Dr. Anthea Kraut, whose tireless and endless support carried me through the ups and downs of this journey. I am indebted to all the social tango dancers who inspired me, particularly in Buenos Aires, and to those who generously gave me their time and attention. I am grateful for my kind mother, Oranous, who always had my back. And lastly, but far from least, I thank my wife Oldřiška, who whenever I am stuck, magically has a solution. iv To all beings who strive to connect on multiple levels, and find words insufficient to express themselves. v ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Social Tango Dancing in the Age of Neoliberal Competition by Radman Shafie Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Critical Dance Studies University of California, Riverside, June 2019 Dr. -

December 2019 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wed

December 2019 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wed. Thursday Friday Saturday 1 TANGO 2 3 4 5 TANGO 6 TANGO 7 TANGO Studio for Rent Studio for Rent Studio for Rent Mimosas and Movement Studio for Rent 11:00-12:00 Tango 102 Week 5 8 am – 6 pm 8 am – 6:30 pm 6:30-7:30 ROLLOUT Volcadas/Colgadas 1-4 pm 8:00 am – 7:00 pm 12:00-1:00 Beginning Tango 2pm–6 pm, 8-10pm Paradise Practica 1:00-2:00 Interm/Adv Tango Blues Dancing Dance & Debauchery: 7:00-10:00 pm Class/Milonga at Hustle & West Coast 7:30-8:00 Intro Class Leading for Followers 2:00-3:00 Stretch & Balance 6:30-9:30 pm The 818 Project (not a Paradise Tango Medici’s 8:00-9:00 pm Practica 7:00-8:00 pm PRIVATE LESSONS event)) 6:30-10:30 pm (not a Paradise Tango Nuevo, Alternative, Zouk (not at Paradise Tango) event) Paradise Milonga 3:00 – 7:00 pm WCS and Hustle: 7-10 pm 8:00-11:00 8 TANGO 9 Studio for Rent 10 11 12 TANGO 13 TANGO 14 8 am – 7 pm Studio for Rent Private Event 1:00-2:00pm Studio for Rent 11:00-12:00 Tango 102 Week 6 Studio for Rent Women’s Technique with 8 am – 6:30 pm 6:30-7:30 ROLLOUT 8:00 am – 5:30 Private Event 3:00-4:00pm 12:00-1:00 Beginning Tango 2pm–6 pm, 8-10pm Olesya (not PT) Paradise Practica Studio for Rent 1:00-2:00 Interm/Adv Tango 6:00 -7:00 pm Class/Milonga at Hustle & West Coast 7:30-8:00 Intro Class WINE & TANGO Available 8-1:00 pm or 2:00-3:00 Stretch & Balance 6:30-9:30 pm Hustle & West Coast Medici’s 8:00-9:00 pm Practica 2:00-3:00 pm or 4-10 pm PRIVATE LESSONS 7:00-9:00 pm 6:30-10:30 pm (not a Paradise Tango Paradise Milonga (not at Paradise Tango) event) NO PRIVATE -

Redalyc.El Giro Patrimonial Del Tango: Políticas Oficiales, Turismo Y

Cuadernos de Antropología Social ISSN: 0327-3776 [email protected] Universidad de Buenos Aires Argentina Morel, Hernán El giro patrimonial del tango: políticas oficiales, turismo y campeonatos de baile en la ciudad de Buenos Aires Cuadernos de Antropología Social, núm. 30, 2009, pp. 155-172 Universidad de Buenos Aires Buenos Aires, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=180913916009 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Cuadernos de Antropología Social Nº 30, pp. 155–172, 2009 © FFyL – UBA – ISSN: 0327-3776 El giro patrimonial del tango: políticas oficiales, turismo y campeonatos de baile en la ciudad de Buenos Aires Hernán Morel* RESUMEN En este artículo nos proponemos analizar algunos aspectos del proceso de activación patri- monial del tango en base a la intervención del Estado local a fi nes de los años ’90. Luego de analizar ciertos aspectos que caracterizan y rigen los procesos de patrimonialización contem- poráneos, relevamos las principales normativas y actividades culturales instituidas en torno al tango. Posteriormente, nos concentramos en el desarrollo de una sucesión de políticas públicas y actividades vinculadas a festivales y campeonatos de baile en la ciudad de Buenos Aires. Asimismo, exploramos las construcciones y los sentidos de “autenticidad” en distintas dimensiones culturales. Por un lado, nos enfocamos en el “turismo cultural” vinculado al tango en la ciudad, mientras que, por otro lado, analizamos los sentidos otorgados a las performances de tango-danza de salón en el contexto de los campeonatos ofi ciales. -

Vortrag / Workshop – Edo Für Tänzer

argentango Zürich, September 2013 Dear organisers of Argentine tango, recently an interested organiser said that he is quite enthusiastic about Argentangos weekend on the Gran Orquestas of the Epoca de Oro, but has organised Joaquin Amenábar already. He could not imagine that it would make sense to schedule Argentango as well as Amenábar. Besides, since autumn 2012 there has been a book from Michael Lavocah on the market about the Gran Orquestas. We are sure that in short time we will hear that Argentangos lecture weekend does not make sense anymore, because now one can read Michael Lavocah’s book. This view of the topic is too one dimensional for Argentango. The workshop GOs of the EdO has as its key element dancing with the music instead of against it for 90% of dances. This is something that few can achieve in one or two weekend events and/or a book. Once introduced, this topic keeps dancers occupied for years, on different levels of knowledge – and in our opinion for the rest of the dancing life. It is not a coincidence that in Europe there now exists a chance on three different paths to introduce concepts which in most common classes are missed out. For two or three years now Europe has finally been ready for this central topic in Argentine tango, this catalyst in the development of dance. The different concepts and exercises, pictures and words from the three complementary paths will increase the prospects of dancers which use these offers together. That is why we from Argentango recommend warmly to organisers in every local scene, not to decide between Amenábar or Argentango, but to realise both offers and in parallel to recommend the book of Lavocah over and over again to their dancers and to have it always on stock for selling. -

MEET the INSTRUCTORS Alicia and Eduardo the Dancers Alicia And

MEET THE INSTRUCTORS Alicia and Eduardo The dancers Alicia and Eduardo Lazarowski grew up in Buenos Aires and moved to North Carolina in 1986 to pursue their careers in health sciences. Eduardo, a biochemist, is an associate professor at UNC Chapel Hill. Alicia is global marketing manager at a medical diagnostics company in Durham. And they love and dance tango, the music of their hometown. Alicia and Eduardo became members of the Raleigh- Durham-Chapel Hill (The Triangle) tango community since 2002 and both have served as President of Triangle Tango between 2008-2013. The Lazarowskis travel regularly to Buenos Aires and through the U.S. to train with world-renowned dancers and instructors, including Alicia Pons, Lorena Ermocida, Fernanda Japas & Alberto Sendra, Facundo Posadas, Oscar Casas, Marcela Duran, Luis Rojas, and Tomas Howlin. Alicia and Eduardo have been regular Argentine tango performers at the NC International Festival (Raleigh NC) since 2007, and have also performed at Duke University and NC Central University (Durham NC), Craven Community College (New Bern NC), and the Spoleto Tango Festival (Charleston SC). They have danced with Maestro bandoneonist Julian Hasse at Music at the Porch (UNC Chapel Hill) and the Diamante Latino festival (Raleigh) and with singer Lorena Guillan at the Triad Stage Theater in Greensboro (NC). Milonga organizers Alicia and Eduardo organized the Milonga del Ocho at Metro 8 (2010-2012) and Pichuqueando at Piazza Italia (2012-2013) in Durham. They currently organize Milonga La Durhamite in Triangle Dance Studio every 4th Friday of the month. DJs Alicia and Eduardo have been mentored and inspired in the art of musicalizing by Osvaldo Natucci (international DJ and lecturer), Lorena Bouzas (DJ at Club Gricel, Buenos Aires), and Carlos Rey (DJ at El Beso, Buenos Aires). -

Barrios, Calles Y Plazas De La Ciudad De Buenos Aires : Origen Y Razón De Sus Nombres

Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires Jefe de Gobierno Mauricio Macri Vicejefa de Gobierno Gabriela Michetti Ministro de Cultura Hernán Lombardi Subsecretaria de Cultura Josefina Delgado Directora General de Patrimonio e Instituto Histórico Liliana Barela Piñeiro, Alberto Gabriel Barrios, calles y plazas de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires : origen y razón de sus nombres . - 1a ed. - Buenos Aires : Dirección General Patrimonio e Instituto Histórico, 2008. 496 p. ; 20x14 cm. ISBN 978-987-24434-5-0 1. Historia de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. I. Título CDD 982.011 Fecha de catalogación: 26/8/2008 © 1983 1ª ed. Instituto Histórico de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. © 1997 2ª ed. Instituto Histórico de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. ISBN 978-987-24434-5-0 © 2008 Dirección General Patrimonio e Instituto Histórico Avda. Córdoba 1556, 1º Piso (1055) Buenos Aires, Argentina Tel. 54 11 4813-9370/5822 Correo electrónico: [email protected] Dirección editorial Liliana Barela Supevisión de la edición Lidia González Investigación Elsa Scalco Edición Rosa De Luca Corrección Marcela Barsamian Nora Manrique Diseño editorial Fabio Ares Hecho el depósito que marca la Ley 11.723. Libro de edición argentina. Impreso en la Argentina. No se permite la reproducción total o parcial, el almacenamiento, el alquiler, la transmisión o la transformación de este libro, en cualquier forma o por cualquier medio, sea electrónico o mecánico, mediante fotocopias, digitalización u otros métodos, sin el permiso previo y escrito del editor. Su infracción está penada por las leyes 11.723 y 25.446. BARRIOS, CALLES Y PLAZAS de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires Origen y razón de sus nombres Alberto Gabriel Piñeiro A BUENOS AYRES, MILKMAN (LECHERO EN BUENOS AIRES) Aguafuerte coloreada publicada en el periódico The Ilustrated London News del 5 de junio de 1858.