37<? /Vg/J No,3O9<?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concert Program

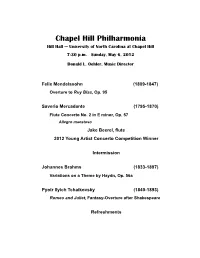

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Hill Hall — University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 6, 2012 Donald L. Oehler, Music Director Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Overture to Ruy Blas, Op. 95 Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870) Flute Concerto No. 2 in E minor, Op. 57 Allegro maestoso Jake Beerel, flute 2012 Young Artist Concerto Competition Winner Intermission Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) Romeo and Juliet, Fantasy-Overture after Shakespeare Refreshments Inspirations William Shakespeare conveyed the overwhelming impact of Julius Caesar in imperial Rome: “Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world like a Colussus.” So might 19th century composers have viewed the figure of Ludwig van Beethoven. With his Symphony No. 3, known as Eroica, composed in 1803, Beethoven radically altered the evolution of symphonic music. The work was inspired by Napoléon Bonaparte’s republican ideals while rejecting that ‘hero’s’ assumption of an imperial mantle. Beethoven broke precedent by employing his art “as a vehicle to convey beliefs,” expanding beyond compositional technique to add the “dimension of meaning and interpretation. All the more remarkable…the high priest of absolute music, effected this change.” (composer W.A. DeWitt) Beethoven, in a word, brought Romanticism to the concert hall, “replac[ing] the Enlightenment cult of reason with a cult of instinct, passion, and the creative genius as virtual demigod. The Romantics seized upon Beethoven’s emotionalism, his sense of the individual as hero.” (composer/writer Jan Swafford) The expression of this new sensibility took many forms, ranging from intensified expression within classical forms, exemplified by Felix Mendelssohn or Johannes Brahms, to the unbridled fervor of Piyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the revolutionary virtuosity and structural innovations of Franz Liszt, the hallucinatory visions of Hector Berlioz, and the megalomania of Richard Wagner. -

Eric Mandat's Chips Off the Ol' Block

California State University, Northridge FLUTTER, SWING, AND SQUAWK: ERIC MANDAT’S CHIPS OFF THE OL’ BLOCK A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Music in Performance By Nicole Irene Moran December 2012 Thesis of Nicole Irene Moran is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Lawrence Stoffel Date ___________________________________ ___________________ Professor Mary Schliff Date ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Julia Heinen, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Dedicated to: Robert Paul Moran (12/13/39- 8/6/11) iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ii Dedication iii Abstract v FLUTTER, SWING, AND SQUAWK: ERIC MANDAT’S CHIPS OFF THE OL’ BLOCK 1 Recital Program 26 Bibliography 27 iv ABSTRACT FLUTTER, SWING, AND SQUAWK: ERIC MANDAT’S CHIPS OFF THE OL’ BLOCK By Nicole Irene Moran Master of Music in Performance The bass clarinet first appeared in the music world as a supportive instrument in orchestras, wind ensembles and military bands, but thanks to Giuseppe Saverio Raffaele Mercadante’s opera Emma d'Antiochia (1834), the bass clarinet began to embody the role of a soloist. Important passages in orchestral works such as Strauss’ Don Quixote (1898) and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring (1913) further advanced the perception of the bass clarinet as a solo instrument, and beginning in the 1970’s, composers such as Harry Sparnaay and Brian Ferneyhough began writing solo works for unaccompanied bass clarinet. In the twenty-first century, clarinet virtuoso and composer Eric Mandat experiments with the capabilities of the bass clarinet in his piece Chips Off the Ol’ Block, utilizing enormous registral leaps, techniques such as multiphonics and quarter-tone fingerings, as well as incorporating jazz-inspired rhythms into the music. -

Saverio MERCADANTE

SAVERIOMERCADANTE Flute Concertos Nos. 1, 2 and 4 Patrick Gallois, Flute and Conductor Sinfonia Finlandia Jyväskylä Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870): here, not only in the Largo, but also at various points in the which the soloist plays from the start, in the first of no fewer faster movements either side of it, providing an effective than five entries, one of which (the second) introduces a new Flute Concertos Nos. 1, 2 and 4 contrast to the more acrobatic writing and brighter rhythms. In theme and another (the fourth) sees a modulation to the Saverio Mercadante was born in 1795 in the southern Italian 18) and a trio for flute, violin and guitar (1816). The young the Allegro maestoso, the most demanding of the movements minor. These five sections alternate with four brief orchestral town of Altamura. Between 1808 and 1819 he studied the composer’s interest in the flute, an instrument which at that from a formal point of view, orchestral interludes separate interludes, reduced in both scale and significance. violin, cello, bassoon, clarinet and flute, as well as composition time had yet to be fully technically developed, stemmed three substantial passages in which the soloist is called on The title-page of the Flute Concerto No. 1, Op. 49, (under Giovanni Furno, Giacomo Tritto and Nicola Zingarelli), from his everyday life at the conservatory, where he was to play all kinds of embellishments, high-speed passages gives both its date of composition, 1813, and the name of its at the conservatory of Naples, then known as the Royal mixing with virtuoso teachers and fellow students – the best (including octave leaps, extended chromatic passages, dedicatee, Mercadante’s fellow student Pasquale Buongiorno, College of Music. -

MWV Saverio Mercadante

MWV Saverio Mercadante - Systematisches Verzeichis seiner Werke vorgelegt von Michael Wittmann Berlin MW-Musikverlag Berlin 2020 „...dem Andenken meiner Mutter“ November 2020 © MW- Musikverlag © Michael Wittmann Alle Rechte vorbehalten, insbesondere die des Nachdruckes und der Übersetzung. !hne schriftliche Genehmigung des $erlages ist es auch nicht gestattet, dieses urheberrechtlich geschützte Werk oder &eile daraus in einem fototechnischen oder sonstige Reproduktionverfahren zu verviel"(ltigen oder zu verbreiten. Musikverlag Michael Wittmann #rainauerstraße 16 ,-10 777 Berlin /hone +049-30-21*-222 Mail4 m5 musikverlag@gmail com Vorwort In diesem 8ahr gedenkt die Musikwelt des hundertfünzigsten &odestages 9averio Merca- dantes ,er Autor dieser :eilen nimmt dies zum Anlaß, ein Systematisches Verzeichnis der Wer- ke Saverio Mercdantes vorzulegen, nachdem er vor einigen 8ahren schon ein summarisches Werkverzeichnis veröffentlicht hat <Artikel Saverio Mercadante in: The New Groves ictionary of Musik 2000 und erweitert in: Neue MGG 2008). ?s verbindet sich damit die @offnung, die 5eitere musikwissenschaftliche ?rforschung dieses Aomponisten zu befördern und auf eine solide philologische Grundlage zu stellen. $orliegendes $erzeichnis beruht auf einer Aus5ertung aller derzeit zugänglichen biblio- graphischen Bindmittel ?in Anspruch auf $ollst(ndigkeit 5(re vermessen bei einem Aom- ponisten 5ie 9averio Mercadante, der zu den scha"fensfreudigsten Meistern des *2 8ahrhunderts gehört hat Auch in :ukunft ist damit zu rechnen, da) 5eiter Abschriften oder bislang unbekannte Werke im Antiquariatshandel auftauchen oder im :uge der fortschreitenden Aata- logisierung kleinerer Bibliotheken aufgefunden 5erden. #leichwohl dürfte (mit Ausnahme des nicht vollst(ndig überlieferten Brüh5erks> mit dem Detzigen Borschungsstand der größte &eil seiner Werk greifbar sein. ,ie Begründung dieser Annahme ergibt sich aus den spezi"ischen #egebenheiten der Mercadante-Überlieferung4 abgesehen von der frühen Aonservatoriumszeit ist Mercdante sehr sorgfältig mit seinen Manuskripten umgegangen. -

Schiller and Music COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Schiller and Music COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Schiller and Music r.m. longyear UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 54 Copyright © 1966 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Longyear, R. M. Schiller and Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469657820_Longyear Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Longyear, R. M. Title: Schiller and music / by R. M. Longyear. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 54. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1966] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 66064498 | isbn 978-1-4696-5781-3 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5782-0 (ebook) Subjects: Schiller, Friedrich, 1759-1805 — Criticism and interpretation. -

De Lane, by the Author and Sold by All Booksellers, [C

vis04njf Section name Library Special Collections Service Baron Collection Handlist 2 GREAT BRITAIN Catalogue: ordered alphabetically 1 BAGSHAWE, Rev. C. F. Ambrosden : ‘There shall be no night there’ Rev.XXI.25. / Words from Hymns A & M. No 23 ; Music by Rev. C. F. Bagshawe. MA. – Ambrosden : [s.n.], Nov. 1866. – Single leaf printed on one side ; 280 x 225 mm. 2 BEULER, Jacob. The figity man, comic song, / by J. Beuler. – London : Published by J. Beuler, 42, Bemerton Strt, Caledonian Road, King’s Cross ; Sold by Purday…Keith & Prowse… Monro & May, *c. 1845+. – 5 + [1] p. ; 346 x 244 mm. 3 BLOCKLEY, John. The Arab’s farewell, to his favorite steed, / written by the Honble Mrs Norton, / composed by John Blockley. – London : Addison & Hodson, 210, Regent Street… and 47, King Street, [c. 1844-48]. – 7 + [1] p. ; 348 x 255 mm. 4 A child’s hymn, / set to music by a blind girl for the benefit of an aged man who is blind and destitute. – [Exeter] : W. Spreat, Lith, [c. 1850]. – Single leaf printed on one side ; 343 x 248 mm. 5 Detail of the exercise of Light Infantry and the bugle sounds of the Royal Sappers & Miners. – Second edition. – Chatham : Lithographed at the Establishment for Field Instruction Royal Engineer Department, 1823. – [4], 20 p. ; 215 x 130 mm. 6 The Englishwoman’s quadrilles / dedicated by the composer to the subscribers of the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine. – London : Vincent Brooks, Lith, [c. 1860]. – 4 p. ; 344 x 255 mm. 7 GILLESPIE, Maria. The ‘Adieu polka’, / composed by Miss Maria Gillespie, and dedicated to Mrs Fitzgibbon, Sidney House. -

New on Naxos | November 2013

NEWThe World’s O LeadingN ClassicalNAX MusicOS Label NOVEMBER 2013 This Month’s Other Highlights © 2013 Naxos Rights US, Inc. • Contact Us: [email protected] www.naxos.com • www.classicsonline.com • www.naxosmusiclibrary.com • blog.naxos.com NEW ON NAXOS | NOVEMBER 2013 Leonard Slatkin Maurice RAVEL (1875–1937) Orchestral Works, Volume 2 Orchestre National de Lyon • Leonard Slatkin Valses nobles et sentimentales Gaspard de la nuit (orch. Marius Constant) Le tombeau de Couperin • La valse Maurice Ravel’s Valses nobles et sentimentales present a vivid mixture of atmospheric impressionism, intense expression and modernist wit, his fascination with the waltz further explored in La valse, a mysterious evocation of a vanished imperial epoch. Heard here in an orchestration by Marius Constant, Gaspard de la nuit is Ravel’s response to the other-worldly poems of Aloysius Bertrand, and the dance suite Le tombeau de Couperin is a tribute to friends who fell in the war of 1914-18 as well as a great 18th century musical forbear. ‘It is a delightful and assorted collection… presented in splendid performances by the Orchestre National de Lyon led by their music director, the venerable American conductor Leonard Slatkin.’ (Classical.net / Volume 1, 8.572887) Volume 1 of this series of Ravel’s orchestral music (8.572887 and NBD0030) has proved an immediate hit and has been warmly received by the press. Gramophone admired Leonard Slatkin’s ‘affinity with [Ravel’s] particular world of sound’, and of the Orchestre National de Lyon, stated that ‘it augurs well as a companion to the orchestra’s Debussy set 8.572888 Playing Time: 66:39 under Jun Märkl.’ The Blu-ray version provides a spectacular alternative to CD, ‘the orchestral colors… are beautifully realized by Slatkin and his forces, and well-preserved in either hi-res format’ (Audiophile Audition 7 47313 28887 8 5-star review). -

Departmental Programs

Prairie View A&M University Henry Music Library 3/29/2017 Departmental Programs Spring 2016 Senior Recital Najee Bell, bassoon Dr. Vicki Seldon, piano January 14, 2016 Trk. 1 Concerto in B-flat Major for Bassoon and Orchestra K 191 (W.A. Mozart) Trk. 2 Berceuse (Igor Stravinsky) (from Firebird Suite) Trk. 3 Concerto in e minor for Bassoon and Orchestra RV 484 (Antonio Vivaldi) Allegro Poco Andante Allegro Trk. 4 Sonata for Bassoon and Piano (Paul Hindemith) Leicht bewegt Langsam. Marsch. Pastorale Seminar February 25, 2016 Trk. 1 Rend’il sereno al ciglio (G. F. Handel) Daphne Webb, mezzo-soprano (from Sosarme) Trk. 2 Morceau de Concours (Gabriel Fauré) DeAndre Smith, flute Trk. 3 Batti, batti, o bel Massetto (Mozart) Jasmine Currie, soprano (from Don Giovanni) Trk. 4 Gavotte (Francois-Joseph Gossec) Wendell Harris, trombone Trk. 5 Lascia ch’io pianga (G.F. Handel) Ashley Scott, soprano Sonata for Flute and Piano (Francis Poulenc) Allen Theodore, flute Trk. 6 Allegro malinconico Trk. 7 Cantilena Trk. 8 Presto giocoso PVAMU Orchestra Wendy I. Bergin, director March 29, 2016 Don Quixote Suite (G. P. Telemann) Trk. 1 2. Le réveil de Quichotte Trk. 2 3. Son attaque des moulins à vent Trk. 3 4. Ses soupirs amoureux après la Princesse Dulcinée Trk. 4 5. Sanche Panse berné Trk. 5 6. Le galope de Rosinante 7. Celui d’ane de Sanche Trk. 6 8. Le couché de Quichotte Trk. 7 Chester Chorale (William Billings) Chester Variations (Billings/arr. Vaclav Nehlybel) Trk. 8 Tuscaloosa Tango (Daniel Leo Simpson) Seminar March 31, 2016 Trk. -

The Offical History of The

1965 © The Birmingham News THE OFFICAL HISTORY OF THE 1921-1955: Beginnings 1949-50 season with Dorsey Whittington, the orchestra’s first conductor, appearing as soloist in the fourth concert, The Alabama Symphony Orchestra can trace its beginnings playing Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto. to 1921, when on Friday, April 29, fifty-two volunteer musicians joined to perform at the Birmingham Music Festival at In 1951, the orchestra began its long association with the Old Jefferson Theater. It was not until 1933, however, the Festival of Arts. There were several support groups that the orchestra gave its first “formal” concert when the formed in these early years. The Vanguards, a group Birmingham Music Club presented the orchestra, under the mostly of young couples, produced its own magazine and direction of Dorsey Whittington, at Phillips High School. published the concert programs. Another support group, the Symphonettes, was organized in October 1954. It later On October 23, 1933, the Birmingham Symphony Association changed its name to the Symphony League. was officially formed and J.J. Steiner was installed as president. With a budget of $7,000, four concerts were planned for its first season. By the 1935-36 season, the 1956-1979: Early Growth orchestra had as many as eighty players, and a budget of In 1956, the orchestra changed its name to the Birmingham $410,000. A full rehearsal cost $100 and guest artists’ fees Symphony Orchestra and became fully professional. Up were low by today’s standards- the renowned composer- until that time some of its musicians had been paid weekly pianist, Percy Grainger, was paid $350 for his appearance salaries, some by the rehearsal or concert, and some with the orchestra in October 1939. -

A Letter by the Composer About "Giovanni D'arco" and Some Remarks on the Division of Musical Direction in Verdi's Day Martin Chusid

Performance Practice Review Volume 3 Article 10 Number 1 Spring A Letter by the Composer about "Giovanni d'Arco" and Some Remarks on the Division of Musical Direction in Verdi's Day Martin Chusid Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Chusid, Martin (1990) "A Letter by the Composer about "Giovanni d'Arco" and Some Remarks on the Division of Musical Direction in Verdi's Day," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 3: No. 1, Article 10. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199003.01.10 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol3/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tempo and Conducting in 19th-century Opera A Letter by the Composer about Giovanna d'Arco and Some Remarks on the Division of Musical Direction in Verdi's Day Martin Chusid Vcnezia 28 Marzo 1845 Venice 28 March 1845 Carissimo Romani My very dear Romani Ti ringrazio dei saluti mandalimi dalla Thank you for conveying Mme Bortolotti.1 Tu vuoi che t'accenni aleune Bortolotti's greetings. You want me cose sul la Giovanna? Tu non ne to point out some things about abbisogni, e sai bene inlerpretare da te; Giovanna? You don't need them, and ma se ti fa piacere che te ne dica are well able to interpret by yourself; qualcosa; cccomi a saziarti [?]. -

From the Glicibarifono to the Bass Clarinet.Pdf

From the Glicibarifono to the Bass Clarinet: A Chapter in the History of Orchestration in Italy* Fabrizio Della Seta From the very beginnings of opera, the work of the theatre composer was carried out in close contact with, if not founded upon, the performer. At least until half-way through the nineteenth century, a composer would be judged in large part on his ability to make best use of the vocal resources of the singers for whom he was writing in a given season, to model his music on their individual qualities in the same way as (in terms of an often- repeated image) a tailor models the suit to the contours of his client's body, or (to use a more noble comparison) as a sculptor exploits the particular material characteristics of a block of marble. Even Verdi at the time of his greatest prestige, when he was in a position to impose his dramatic ideas in an almost dictatorial manner, drew inspiration from the abilities of respected performers, e.g. from Teresa Stolz for Aida or Giuseppina Pasqua for Falstaff. To a less decisive extent, but according to a concept similar in every respect, the same principle had been applied to the instrumental aspect of opera since the early decades of the eighteenth century, when the orchestra began to assume growing importance in the structure of a work. Often the presence in the theatre orchestra of a gifted instrumentalist would lead the composer to assign to him a prominent solo, almost always as if competing with voice as an obbligato part, and there were cases in which instrumentalist and composer coincided, as happened in certain operas by Handel. -

Saverio MERCADANTE

SAVERIOMERCADANTE Concerto for Two Flutes Flute Concerto No. 6 • 20 Capricci Patrick Gallois, Flute and Conductor Kazunori Seo, Flute Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice Saverio 20 Capricci for flute (c. 1811–14) .................................................................................................29:19 ¡ I. Largo .................................................................................................................................................... 2:03 ™ II. Allegro ................................................................................................................................................ 1:12 MERCADANTE £ (1795–1870) III. Andante ............................................................................................................................................. 2:23 ¢ IV. Allegro ............................................................................................................................................... 1:05 – V. Allegro ................................................................................................................................................ 1:18 Flute Concertos, Volume 2 · 20 Capricci § VI. Allegro ............................................................................................................................................... 1:27 ¶ VII. Largo ................................................................................................................................................ 1:47 • VIII. Allegro ............................................................................................................................................