Jeremy Dibble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Generazione Dell'ottanta and the Italian Sound

LA GENERAZIONE DELL’OTTANTA AND THE ITALIAN SOUND A DISSERTATION IN Trumpet Performance Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS by ALBERTO RACANATI M.M., Western Illinois University, 2016 B.A., Conservatorio Piccinni, 2010 Kansas City, Missouri 2021 LA GENERAZIONE DELL’OTTANTA AND THE ITALIAN SOUND Alberto Racanati, Candidate for the Doctor of Musical Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2021 ABSTRACT . La Generazione dell’Ottanta (The Generation of the Eighties) is a generation of Italian composers born in the 1880s, all of whom reached their artistic maturity between the two World Wars and who made it a point to part ways musically from the preceding generations that were rooted in operatic music, especially in the Verismo tradition. The names commonly associated with the Generazione are Alfredo Casella (1883-1947), Gian Francesco Malipiero (1882-1973), Ildebrando Pizzetti (1880-1968), and Ottorino Respighi (1879- 1936). In their efforts to create a new music that sounded unmistakingly Italian and fueled by the musical nationalism rampant throughout Europe at the time, the four composers took inspiration from the pre-Romantic music of their country. Individually and collectively, they embarked on a journey to bring back what they considered the golden age of Italian music, with each one yielding a different result. iii Through the creation of artistic associations facilitated by the fascist government, the musicians from the Generazione established themselves on the international scene and were involved with performances of their works around the world. -

Concert Program

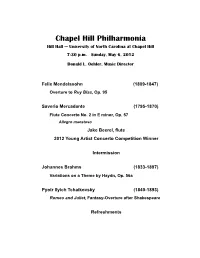

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Hill Hall — University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 6, 2012 Donald L. Oehler, Music Director Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Overture to Ruy Blas, Op. 95 Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870) Flute Concerto No. 2 in E minor, Op. 57 Allegro maestoso Jake Beerel, flute 2012 Young Artist Concerto Competition Winner Intermission Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) Romeo and Juliet, Fantasy-Overture after Shakespeare Refreshments Inspirations William Shakespeare conveyed the overwhelming impact of Julius Caesar in imperial Rome: “Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world like a Colussus.” So might 19th century composers have viewed the figure of Ludwig van Beethoven. With his Symphony No. 3, known as Eroica, composed in 1803, Beethoven radically altered the evolution of symphonic music. The work was inspired by Napoléon Bonaparte’s republican ideals while rejecting that ‘hero’s’ assumption of an imperial mantle. Beethoven broke precedent by employing his art “as a vehicle to convey beliefs,” expanding beyond compositional technique to add the “dimension of meaning and interpretation. All the more remarkable…the high priest of absolute music, effected this change.” (composer W.A. DeWitt) Beethoven, in a word, brought Romanticism to the concert hall, “replac[ing] the Enlightenment cult of reason with a cult of instinct, passion, and the creative genius as virtual demigod. The Romantics seized upon Beethoven’s emotionalism, his sense of the individual as hero.” (composer/writer Jan Swafford) The expression of this new sensibility took many forms, ranging from intensified expression within classical forms, exemplified by Felix Mendelssohn or Johannes Brahms, to the unbridled fervor of Piyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the revolutionary virtuosity and structural innovations of Franz Liszt, the hallucinatory visions of Hector Berlioz, and the megalomania of Richard Wagner. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

Eric Mandat's Chips Off the Ol' Block

California State University, Northridge FLUTTER, SWING, AND SQUAWK: ERIC MANDAT’S CHIPS OFF THE OL’ BLOCK A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Music in Performance By Nicole Irene Moran December 2012 Thesis of Nicole Irene Moran is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Lawrence Stoffel Date ___________________________________ ___________________ Professor Mary Schliff Date ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Julia Heinen, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Dedicated to: Robert Paul Moran (12/13/39- 8/6/11) iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ii Dedication iii Abstract v FLUTTER, SWING, AND SQUAWK: ERIC MANDAT’S CHIPS OFF THE OL’ BLOCK 1 Recital Program 26 Bibliography 27 iv ABSTRACT FLUTTER, SWING, AND SQUAWK: ERIC MANDAT’S CHIPS OFF THE OL’ BLOCK By Nicole Irene Moran Master of Music in Performance The bass clarinet first appeared in the music world as a supportive instrument in orchestras, wind ensembles and military bands, but thanks to Giuseppe Saverio Raffaele Mercadante’s opera Emma d'Antiochia (1834), the bass clarinet began to embody the role of a soloist. Important passages in orchestral works such as Strauss’ Don Quixote (1898) and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring (1913) further advanced the perception of the bass clarinet as a solo instrument, and beginning in the 1970’s, composers such as Harry Sparnaay and Brian Ferneyhough began writing solo works for unaccompanied bass clarinet. In the twenty-first century, clarinet virtuoso and composer Eric Mandat experiments with the capabilities of the bass clarinet in his piece Chips Off the Ol’ Block, utilizing enormous registral leaps, techniques such as multiphonics and quarter-tone fingerings, as well as incorporating jazz-inspired rhythms into the music. -

Saverio MERCADANTE

SAVERIOMERCADANTE Flute Concertos Nos. 1, 2 and 4 Patrick Gallois, Flute and Conductor Sinfonia Finlandia Jyväskylä Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870): here, not only in the Largo, but also at various points in the which the soloist plays from the start, in the first of no fewer faster movements either side of it, providing an effective than five entries, one of which (the second) introduces a new Flute Concertos Nos. 1, 2 and 4 contrast to the more acrobatic writing and brighter rhythms. In theme and another (the fourth) sees a modulation to the Saverio Mercadante was born in 1795 in the southern Italian 18) and a trio for flute, violin and guitar (1816). The young the Allegro maestoso, the most demanding of the movements minor. These five sections alternate with four brief orchestral town of Altamura. Between 1808 and 1819 he studied the composer’s interest in the flute, an instrument which at that from a formal point of view, orchestral interludes separate interludes, reduced in both scale and significance. violin, cello, bassoon, clarinet and flute, as well as composition time had yet to be fully technically developed, stemmed three substantial passages in which the soloist is called on The title-page of the Flute Concerto No. 1, Op. 49, (under Giovanni Furno, Giacomo Tritto and Nicola Zingarelli), from his everyday life at the conservatory, where he was to play all kinds of embellishments, high-speed passages gives both its date of composition, 1813, and the name of its at the conservatory of Naples, then known as the Royal mixing with virtuoso teachers and fellow students – the best (including octave leaps, extended chromatic passages, dedicatee, Mercadante’s fellow student Pasquale Buongiorno, College of Music. -

MWV Saverio Mercadante

MWV Saverio Mercadante - Systematisches Verzeichis seiner Werke vorgelegt von Michael Wittmann Berlin MW-Musikverlag Berlin 2020 „...dem Andenken meiner Mutter“ November 2020 © MW- Musikverlag © Michael Wittmann Alle Rechte vorbehalten, insbesondere die des Nachdruckes und der Übersetzung. !hne schriftliche Genehmigung des $erlages ist es auch nicht gestattet, dieses urheberrechtlich geschützte Werk oder &eile daraus in einem fototechnischen oder sonstige Reproduktionverfahren zu verviel"(ltigen oder zu verbreiten. Musikverlag Michael Wittmann #rainauerstraße 16 ,-10 777 Berlin /hone +049-30-21*-222 Mail4 m5 musikverlag@gmail com Vorwort In diesem 8ahr gedenkt die Musikwelt des hundertfünzigsten &odestages 9averio Merca- dantes ,er Autor dieser :eilen nimmt dies zum Anlaß, ein Systematisches Verzeichnis der Wer- ke Saverio Mercdantes vorzulegen, nachdem er vor einigen 8ahren schon ein summarisches Werkverzeichnis veröffentlicht hat <Artikel Saverio Mercadante in: The New Groves ictionary of Musik 2000 und erweitert in: Neue MGG 2008). ?s verbindet sich damit die @offnung, die 5eitere musikwissenschaftliche ?rforschung dieses Aomponisten zu befördern und auf eine solide philologische Grundlage zu stellen. $orliegendes $erzeichnis beruht auf einer Aus5ertung aller derzeit zugänglichen biblio- graphischen Bindmittel ?in Anspruch auf $ollst(ndigkeit 5(re vermessen bei einem Aom- ponisten 5ie 9averio Mercadante, der zu den scha"fensfreudigsten Meistern des *2 8ahrhunderts gehört hat Auch in :ukunft ist damit zu rechnen, da) 5eiter Abschriften oder bislang unbekannte Werke im Antiquariatshandel auftauchen oder im :uge der fortschreitenden Aata- logisierung kleinerer Bibliotheken aufgefunden 5erden. #leichwohl dürfte (mit Ausnahme des nicht vollst(ndig überlieferten Brüh5erks> mit dem Detzigen Borschungsstand der größte &eil seiner Werk greifbar sein. ,ie Begründung dieser Annahme ergibt sich aus den spezi"ischen #egebenheiten der Mercadante-Überlieferung4 abgesehen von der frühen Aonservatoriumszeit ist Mercdante sehr sorgfältig mit seinen Manuskripten umgegangen. -

Schiller and Music COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Schiller and Music COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Schiller and Music r.m. longyear UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 54 Copyright © 1966 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Longyear, R. M. Schiller and Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469657820_Longyear Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Longyear, R. M. Title: Schiller and music / by R. M. Longyear. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 54. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1966] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 66064498 | isbn 978-1-4696-5781-3 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5782-0 (ebook) Subjects: Schiller, Friedrich, 1759-1805 — Criticism and interpretation. -

La Nuova Musica (1896-1919)

La Nuova Musica (1896-1919) The music periodical La Nuova musica [NMU] was first published on 31 January 1896 by its founder, the pianist and composer Edgardo Del Valle de Paz (1861- 1920), a professor of piano at the Istituto Musicale in Florence, who directed and administered the journal without interruption until its final issue. NMU was published monthly from 1896 to 1907, fortnightly from 1908 to 1910, bimonthly during 1911 and fortnightly from 1912 to its cessation. Throughout the publication pages measuring 34 x 25 cm. are printed in three column format and are numbered beginning with number 1 for successive years. La Nuova musica documents Florentine music history and bridges a gap existing in Italian music periodical literature since 1882, when the earlier Florentine periodical Boccherini (1862-1882) ceased publication. The aim of the periodical is to diffuse by print the most notable music, to raise the musical level of the public by making it aware of the most excellent works of our masters, to give our young composers an opportunity to publicize in print their first compositions, [and] to express openly their opinions. Each issue of NMU contains two sections: testo, features articles about music events and music criticism, and constitutes the main six or eight page section of the periodical; and, musica, a supplement of eight pages consisting of two or three compositions for piano or for voice and piano. This two-fold structure is suspended beginning with the first issue of 1909. The first pages of each issue are generally reserved for a critical essay concerning contemporary topics, followed by an article of historical interest. -

550533-34 Bk Mahler EU

CASELLA Divertimento for Fulvia Donatoni Music for Chamber Orchestra Ghedini Concerto grosso Malipiero Imaginary Orient Orchestra della Svizzera italiana Damian Iorio Alfredo Casella (1883-1947): Alfredo Casella (1883-1947) • Franco Donatoni (1927-2000) Divertimento per Fulvia (Divertimento for Fulvia), Op. 64 (1940) 15:21 Giorgio Federico Ghedini (1892-1965) • Gian Francesco Malipiero (1882-1973) 1 I. Sinfonia (Overture). Allegro vivace e spiritoso, alla marcia 2:05 2 II. Allegretto. Allegretto moderato ed innocente 1:42 ‘A crucial figure: few modern musicians in any country can advised Casella’s parents that to find tuition that would do 3 II. Valzer diatonico (Diatonic Waltz). Vivacissimo 1:43 compare with him for sheer energy, enlightenment and justice to his talent, they would need to send him abroad. persistence in his many-sided activities as leader, 1896 was a watershed in Casella’s life: his father died, 4 VI. Siciliana. Molto dolce e espressivo, come una melodia popolare (Very sweet and expressive, like a folk melody) 2:25 organiser, conductor, pianist, teacher and propagandist – after a long illness; and he moved to Paris with his mother one marvels that he had any time left for composing.’ The to study at the Conservatoire. Casella was to remain in 5 V. Giga (Jig). Tempo di giga inglese (English jig time) (Allegro vivo) 1:54 musician thus acclaimed by the English expert on Italian Paris for almost twenty years, cutting his teeth in the most 6 VI. Carillon. Allegramente 1:05 music John C.G. Waterhouse was Alfredo Casella – who dynamic artistic milieu of the time as pianist, composer, 7 VII. -

Giuseppe Martucci (Geb. Capua, 6. Januar 1856 — Gest. Neapel, 1

Giuseppe Martucci (geb. Capua, 6. Januar 1856 — gest. Neapel, 1. Juni 1909) La Canzone dei Ricordi (1886-87/orch. 1899) Poemetto lirico di Rocco E. Pagliara I Svaniti, non sono i sogni. Andantino p. 1 II Cantava’l ruscello la gaia canzone. Allegretto con moto p. 10 III Fior di ginestra. Andantino – Allegretto giusto – Tempo I p. 35 IV Sul mar la navicella. Allegretto con moto p. 53 V Un vago mormorio mi giunge. Andante p. 66 VI Al folto bosco, placida ombria. Andantino con moto – Allegro agitato – Tempo I p. 83 VII No, svaniti non sono i sogni. Andantino p. 117 Vorwort Als der Pionier der Wiederbelebung der italienischen Instrumentalmusik in einer Zeit, die fast ausschließlich auf die Oper konzentriert war, ist der Römer Giovanni Sgambati (1841-1914) anzusehen, Günstling Liszts und Wagners, exzellenter Pianist, Dirigent und Komponist. Ihm folgte Giuseppe Martucci, Sohn eines Trompeters und Kapellmeisters und ebenfalls als Pianist (von Liszt und Anton Rubinstein bewundert), Dirigent und Komponist eine herausragende, noch weit markantere und schöpferisch fruchtbarere Persönlichkeit. Der Dirigent Martucci setzte in Italien nicht nur Richard Wagners Musik durch (italienische Erstaufführung von Tristan und Isolde am 2. Juni 1888 im Teatro Comunale zu Bologna), sondern setzte sich auch nachdrücklich für Johannes Brahms, Carl Goldmark (1830-1915), Richard Strauss, Edouard Lalo (1823-92), Claude Debussy, Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900), Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) u. a. ein. Siebenjährig trat Martucci erstmals öffentlich als Pianist auf, mit elf Jahren begann er sein Studium am Conservatorio di San Pietro a Majella zu Neapel, wo der Mercadante-Schüler Paolo Serrao (1830-1907) sein Kompositionslehrer war. -

De Lane, by the Author and Sold by All Booksellers, [C

vis04njf Section name Library Special Collections Service Baron Collection Handlist 2 GREAT BRITAIN Catalogue: ordered alphabetically 1 BAGSHAWE, Rev. C. F. Ambrosden : ‘There shall be no night there’ Rev.XXI.25. / Words from Hymns A & M. No 23 ; Music by Rev. C. F. Bagshawe. MA. – Ambrosden : [s.n.], Nov. 1866. – Single leaf printed on one side ; 280 x 225 mm. 2 BEULER, Jacob. The figity man, comic song, / by J. Beuler. – London : Published by J. Beuler, 42, Bemerton Strt, Caledonian Road, King’s Cross ; Sold by Purday…Keith & Prowse… Monro & May, *c. 1845+. – 5 + [1] p. ; 346 x 244 mm. 3 BLOCKLEY, John. The Arab’s farewell, to his favorite steed, / written by the Honble Mrs Norton, / composed by John Blockley. – London : Addison & Hodson, 210, Regent Street… and 47, King Street, [c. 1844-48]. – 7 + [1] p. ; 348 x 255 mm. 4 A child’s hymn, / set to music by a blind girl for the benefit of an aged man who is blind and destitute. – [Exeter] : W. Spreat, Lith, [c. 1850]. – Single leaf printed on one side ; 343 x 248 mm. 5 Detail of the exercise of Light Infantry and the bugle sounds of the Royal Sappers & Miners. – Second edition. – Chatham : Lithographed at the Establishment for Field Instruction Royal Engineer Department, 1823. – [4], 20 p. ; 215 x 130 mm. 6 The Englishwoman’s quadrilles / dedicated by the composer to the subscribers of the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine. – London : Vincent Brooks, Lith, [c. 1860]. – 4 p. ; 344 x 255 mm. 7 GILLESPIE, Maria. The ‘Adieu polka’, / composed by Miss Maria Gillespie, and dedicated to Mrs Fitzgibbon, Sidney House. -

Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Masters Applied Arts 2018 Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930. David Scott Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appamas Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Scott, D. (2018) Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930.. Masters thesis, DIT, 2018. This Theses, Masters is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900–1930 David Scott, B.Mus. Thesis submitted for the award of M.Phil. to the Dublin Institute of Technology College of Arts and Tourism Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama February 2018 i ABSTRACT Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, arrangements of Irish airs were popularly performed in Victorian drawing rooms and concert venues in both London and Dublin, the most notable publications being Thomas Moore’s collections of Irish Melodies with harmonisations by John Stephenson. Performances of Irish ballads remained popular with English audiences but the publication of Stanford’s song collection An Irish Idyll in Six Miniatures in 1901 by Boosey and Hawkes in London marks a shift to a different type of Irish song.