"Magic City" Class, Community, and Reform in Roanoke, Virginia, 1882-1912 Paul R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virginia Board of Nursing

VIRGINIA BOARD OF NURSING Education Informal Conference Committee Agenda March 11, 2105 Department of Health Professions, 9960 Mayland Drive, Suite 300, Henrico, Virginia 23233 Board Room 3 9:00 A.M. Education Informal Conference Committee – Conference Center Suite 201 Committee Members: Jane Ingalls, RN, PhD., Chair Evelyn Lindsay, LPN Request for Full Approval Survey Visit • J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College, LPN to RN Weekend/Part Time Program, Richmond • George Mason University, BSN Program, Fairfax • Virginia Western Community College, ADN RN Program, Roanoke Request for Provisional Approval Survey Visit • Riverside College of Health Careers, ADN RN Program, Newport News Change of Program Status From Conditional to Full Approval • South University, BSN Program, Glen Allen Request for NCLEX Approval • Norfolk State University, ADN Program, Norfolk Request for Curriculum Change • Lord Fairfax Community College, PN Program, Middleton RN Programs Pass Rates Below 80% for Two Years • Centra College of Nursing, ADN Program, Lynchburg • Chamberlain College of Nursing, BSN Program, Arlington • Dabney S. Lancaster Community College, ADN Program, Clifton Forge • ECPI University – Newport News, ADN Program, Newport News • George Mason University, BSN Program, Fairfax • Hampton University, BSN Program, Hampton • Saint Michael College of Allied Health, ADN Alexandria • Stratford Falls Church, BSN Program, Falls Church • Virginia Western Community College, ADN Program, Roanoke PN Programs Pass Rates Below 80% for Two Years • Chester Career -

CONTENTS August 2021

CONTENTS August 2021 I. EXECUTIVE ORDERS JBE 21-12 Bond Allocation 2021 Ceiling ..................................................................................................................... 1078 II. EMERGENCY RULES Children and Family Services Economic Stability Section—TANF NRST Benefits and Post-FITAP Transitional Assistance (LAC 67:III.1229, 5329, 5551, and 5729) ................................................................................................... 1079 Licensing Section—Sanctions and Child Placing Supervisory Visits—Residential Homes (Type IV), and Child Placing Agencies (LAC 67:V.7109, 7111, 7311, 7313, and 7321) ..................................................... 1081 Governor Division of Administration, Office of Broadband Development and Connectivity—Granting Unserved Municipalities Broadband Opportunities (GUMBO) (LAC 4:XXI.Chapters 1-7) .......................................... 1082 Health Bureau of Health Services Financing—Programs and Services Amendments due to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Public Health Emergency—Home and Community-Based Services Waivers and Long-Term Personal Care Services....................................................................................... 1095 Office of Aging and Adult Services—Programs and Services Amendments due to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Public Health Emergency—Home and Community-Based Services Waivers and Long-Term Personal Care Services....................................................................................... 1095 Office -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Consolidated Version of the Sanpin 2.3.2.1078-01 on Food, Raw Material, and Foodstuff

Registered with the Ministry of Justice of the RF, March 22, 2002 No. 3326 MINISTRY OF HEALTH OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION CHIEF STATE SANITARY INSPECTOR OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION RESOLUTION No. 36 November 14, 2001 ON ENACTMENT OF SANITARY RULES (as amended by Amendments No.1, approved by Resolution No. 27 of Chief State Sanitary Inspector of the RF dated 20.08.2002, Amendments and Additions No. 2, approved by Resolution No. 41 of Chief State Sanitary Inspector of the RF dated15.04.2003, No. 5, approved by Resolution No. 42 of Chief State Sanitary Inspector of the RF dated 25.06.2007, No. 6, approved by Resolution No. 13 of Chief State Sanitary Inspector of the RF dated 18.02.2008, No. 7, approved by Resolution No. 17 of Chief State Sanitary Inspector of the RF dated 05.03.2008, No. 8, approved by Resolution No. 26 of Chief State Sanitary Inspector of the RF dated 21.04.2008, No. 9, approved by Resolution No. 30 of Chief State Sanitary Inspector of the RF dated 23.05.2008, No. 10, approved by Resolution No. 43 of Chief State Sanitary Inspector of the RF dated 16.07.2008, Amendments No.11, approved by Resolution No. 56 of Chief State Sanitary Inspector of the RF dated 01.10.2008, No. 12, approved by Resolution No. 58 of Chief State Sanitary Inspector of the RF dated 10.10.2008, Amendment No. 13, approved by Resolution No. 69 of Chief State Sanitary Inspector of the RF dated 11.12.2008, Amendments No.14, approved by Resolution No. -

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

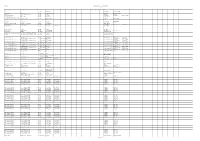

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

Alice in Southwest Virginia: a Financial Hardship Study

ALICE IN SOUTHWEST VIRGINIA: A FINANCIAL HARDSHIP STUDY 2020 SOUTHWEST VIRGINIA REPORT United Way of Southwest Virginia ALICE IN THE TIME OF COVID-19 The release of this ALICE Report for Southwest Virginia comes during an unprecedented crisis — the COVID-19 pandemic. While our world changed significantly in March 2020 with the impact of this global, dual health and economic crisis, ALICE remains central to the story in every U.S. county and state. The pandemic has exposed exactly the issues of economic fragility and widespread hardship that United For ALICE and the ALICE data work to reveal. That exposure makes the ALICE data and analysis more important than ever. The ALICE Report for Southwest Virginia presents the latest ALICE data available — a point-in-time snapshot of economic conditions across the region in 2018. By showing how many Southwest Virginia households were struggling then, the ALICE Research provides the backstory for why the COVID-19 crisis is having such a devastating economic impact. The ALICE data is especially important now to help stakeholders identify the most vulnerable in their communities and direct programming and resources to assist them throughout the pandemic and the recovery that follows. And as Southwest Virginia moves forward, this data can be used to estimate the impact of the crisis over time, providing an important baseline for changes to come. This crisis is fast-moving and quickly evolving. To stay abreast of the impact of COVID-19 on ALICE households and their communities, visit our website at UnitedForALICE.org/COVID19 for updates. ALICE REPORT, JULY 2020 1 SOUTHWEST VIRGINIA ALICE IN SOUTHWEST VIRGINIA INTRODUCTION In 2018, 115,460 households in Southwest Virginia — 51% — could not afford basic needs such as housing, child care, food, transportation, health care, and technology. -

Partnership for a LIVABLE ROANOKE VALLEY PLAN Promoting Economic Opportunity and Quality of Life in the Roanoke Valley

Partnership for a LIVABLE ROANOKE VALLEY PLAN Promoting Economic Opportunity and Quality of Life in the Roanoke Valley SUMMARY IO Final February 2014 REG NA HEALTH CARE REGIONAL A L TE P STRENGTHS EDUCATION LIVABILITY F BO TOUR A S O T IE CR R TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE T IES OF RO A N IT AN I T U C O G K O E F N COMMUNITY REGIONAL ARTS C A R N A LIVABLE E D N FUTURE VALUES INDUSTRY DATA S K R A ROANOKE L L I E N M S OUTDOORS ACADEMICS WELLNESS VALLEY R H O A PRIORITIES COLLABORATION I N P O K E RESOURCES ENVIRONMENT Cover image source: Kurt Konrad Photography Back cover image source: Roanoke Valley Convention and Visitors Bureau SUMMARY LIVABLE ROANOKE VALLEY PLAN My time as Chair of the Partnership for a Livable Roanoke Valley has been eye opening. We have learned detailed information about our region’s strengths and weaknesses. We have studied service organizations, businesses, and local, commonwealth, and federal programs to really understand what’s available in the Roanoke Region. We have asked “what does the future hold for the Roanoke Valley of Virginia” and “how can we ensure a strong quality of life in our communities?” The Partnership for a Livable Roanoke Valley is an initiative of seven local governments and more than 60 organizations in the Roanoke Valley. The initiative seeks to promote economic opportunity and a greater quality of life for all Roanoke Valley residents through the development of the area’s first regional plan for livability. -

Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook

USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Sixth Edition April 2005 U.S. ARMY MEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES FORT DETRICK FREDERICK, MARYLAND Emergency Response Numbers National Response Center: 1-800-424-8802 or (for chem/bio hazards & terrorist events) 1-202-267-2675 National Domestic Preparedness Office: 1-202-324-9025 (for civilian use) Domestic Preparedness Chem/Bio Helpline: 1-410-436-4484 or (Edgewood Ops Center – for military use) DSN 584-4484 USAMRIID’s Emergency Response Line: 1-888-872-7443 CDC'S Emergency Response Line: 1-770-488-7100 Handbook Download Site An Adobe Acrobat Reader (pdf file) version of this handbook can be downloaded from the internet at the following url: http://www.usamriid.army.mil USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Sixth Edition April 2005 Lead Editor Lt Col Jon B. Woods, MC, USAF Contributing Editors CAPT Robert G. Darling, MC, USN LTC Zygmunt F. Dembek, MS, USAR Lt Col Bridget K. Carr, MSC, USAF COL Ted J. Cieslak, MC, USA LCDR James V. Lawler, MC, USN MAJ Anthony C. Littrell, MC, USA LTC Mark G. Kortepeter, MC, USA LTC Nelson W. Rebert, MS, USA LTC Scott A. Stanek, MC, USA COL James W. Martin, MC, USA Comments and suggestions are appreciated and should be addressed to: Operational Medicine Department Attn: MCMR-UIM-O U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) Fort Detrick, Maryland 21702-5011 PREFACE TO THE SIXTH EDITION The Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook, which has become affectionately known as the "Blue Book," has been enormously successful - far beyond our expectations. -

JONESTOWN SURVIVOR Jonestown Survivor an Insider’S Look

JONESTOWN SURVIVOR Jonestown Survivor An Insider’s Look Laura Johnston Kohl iUniverse, Inc. New York Bloomington Jonestown Survivor An Insider’s Look Copyright © 2010 Laura Johnston Kohl All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. iUniverse books may be ordered through booksellers or by contacting: iUniverse 1663 Liberty Drive Bloomington, IN 47403 www.iuniverse.com 1-800-Authors (1-800-288-4677) Because of the dynamic nature of the Internet, any Web addresses or links contained in this book may have changed since publication and may no longer be valid. The views expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them. ISBN: 978-1-4502-2094-1 (pbk) ISBN: 978-1-4502-2096-5 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-4502-2095-8 (ebk) Printed in the United States of America iUniverse rev. date: 3/15/2010 I dedicate this book to my friends from Peoples Temple— those who did and those who did not survive. We united to help improve this world for all people. SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My “Rs”: my husband, Ron, and our son, Raul, have supported me endlessly and deeply to End peace with my past and continue my search for clarity. My mother, Virginia, a survivor, teacher, and author, inspired me and gave me strength to meet the challenges I have faced. -

Virginia's Blue Ridge Roanoke Valley

James River Water Trail public access 611 er iv R Craig 220 s Creek e m a J Arcadia James River43 635 Water Trail 614 630 public access Exit 167 J James River am Water Trail e s R public access iv er Buchanan 606 638 43 81 New Castle 600 11 George Washington Fincastle and Je?erson? National Forest 606 606 630 640 220 Parkway 11 Milepost 86 Peaks of Otter Bedford Reservoir 43 Greenfield 220 Botetourt Sports Complex ail Tr ian ppalach A y Troutville wa ark e P idg e R Blu VISITVABLUERIDGE.COM Daleville DOWNTOWN ROANOKE BLACK DOG SALVAGE 902 13th St. SW B2 21 Orange Ave. McAfee ac 6 DOWNTOWN Appal hian GREATER Roanoke, VA 24016 4 Area code is 540 unless otherwise noted. A Knob Trail B C t 460 xi 540.343.6200 BlackDogSalvage.com E n THINGS TO DO/RECREATION A Southwest Virginia’s Premier Destination p Exit 150 ROANOKE ROANOKE p see Virginia’s for Architectural Antiques & Home Décor. 17 Center in the Square 28 a Blue Ridge Map lac Madison Ave. centerinthesquare.org 342-5700 hi on reverse 902 13th St. SW Roanoke, VA 24016 4 an Trail Blue Ridge 311 Explore 40,000 square feet of Treasures 18 Downtown Roanoke Inc. Carvins Cove from Around the World. Reclaiming and VALLEY alt downtownroanoke.org 342-2028 Reservoir Renewing Salvage is our Passion! Antique Bedford Rec Site 2 Harris Wrought Iron, Stained Glass, Mantels, on Ave 19 Harrison Museum of African American Culture 220 t. 1 SALVAGE .com Garden Statuary, Doors, Vintage House S harrisonmuseum.com 857-4395 h Parts and much more. -

FEATHERS ADORN SOME of the MOST ATTRACTIVE HATS Ostrich Plumes Are Used Effectively, Hanging Over the Head to Suggest the Raglan the Fashionable

8 THE SUN, SUNDAY, OCTOBER 5, 1919. 4 FEATHERS ADORN SOME OF THE MOST ATTRACTIVE HATS Ostrich Plumes Are Used Effectively, Hanging Over the Head to Suggest the Raglan The Fashionable . Picture Hat Appears in Reduced Size and Is Worn for the Most Nicknacks Part in the Evening Veils Show Little Change For Women ning, lend T really looks as though the ostrich whllo older women chooso a themselves admirably for twad- Vnown ns "kitten's ear." the ""most When pockets In plush or vel dling dove-- such skirts arrive, plumo wag on Its way to tho hat black hat of chenille or or draping. Tho ovora, dolicato and silky of pinks. Tho off the fancy bag will to somo extent go vet, ornamented with plumes or jet. downs, duveteens, &c, look muclt color for blouses or four seasons ago I A fow of tho best hats of the year darker Is tho brown out qr style. Tho stylo of veil has not changed thicker than they are; Indeed all tho that la so favored In everything for THREE revived, and many were nro garnished with the feather and they since spring. A closo observer might talent has been pot on tho soft velvety tho street n. pheasant, the HANDBAGS AND PANS. fln nld Rhawln rnAtnrf.l aro very too. Tho plume declare that tho veil Is losing favor. surface, for those materials have not I'ocKots, pockets, and again pockets. successful of over There is less use for It now that the much body. The chiffon velvets, as Wo discovered them at the bocin- - from tho seclusion and darkness Is tho uncurled sort nnd hangs much In vogue as when they appeared F you would Judgo from what tho invisible hair net has been so gener nlng of the war when the British om-c- er some old chest or attlo to bo cut up the hoad In a manner to suggest tho years ago, somo, 01 best places aro displaying you ally' adopted.