English/Law/Crc.Htm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conferencia De Desarme

CONFERENCIA DE DESARME CD/1850 9 de septiembre de 2008 ESPAÑOL Original: INGLÉS CARTA DE FECHA 26 DE AGOSTO DE 2008 DIRIGIDA AL SECRETARIO GENERAL DE LA CONFERENCIA DE DESARME POR EL REPRESENTANTE PERMANENTE DE GEORGIA POR LA QUE TRANSMITE EL TEXTO DE UNA DECLARACIÓN EN QUE ACTUALIZA LA INFORMACIÓN SOBRE LA SITUACIÓN REINANTE EN GEORGIA Tengo el honor de transmitir adjunto el texto de la declaración formulada por la delegación de Georgia en la 1115ª sesión plenaria* de la Conferencia de Desarme, celebrada el 26 de agosto de 2008, sobre la agresión militar de la Federación de Rusia contra el territorio de Georgia, junto con otros documentos conexos. Le agradecería que tuviera a bien hacer distribuir la presente carta, la declaración anexa y los documentos adjuntos como documento oficial de la Conferencia de Desarme. (Firmado): Giorgi Gorgiladze Embajador Representante Permanente de Georgia * El texto de la declaración, tal como fue pronunciada, figura en el documento CD/PV.1115. GE.08-63124 (S) 190908 220908 CD/1850 página 2 El Representante Permanente de Georgia, Embajador Giorgi Gorgiladze, aprovecha la oportunidad para actualizar la información de la Conferencia de Desarme sobre la situación actual en Georgia, que fue objeto de debate en la sesión de la semana pasada. En términos jurídicos, Georgia ha sido sometida a una agresión militar en gran escala por la Federación de Rusia, en violación de los principios y las normas de la Carta de las Naciones Unidas, incluida la prohibición del uso de la fuerza entre los Estados y el respeto de la soberanía y la integridad territorial de Georgia. -

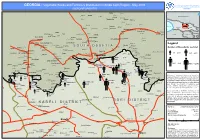

Map Sub-Title

Vegetable Seeds and FertilizersM Distributionap Sub-T init Shidale Kartli Region - May 2009 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations GEORGIA - MAP TITLE - Emergency Rehabilitation Coordination Unit Da(OSRO/GEO/803/ITA)te (dd mmm yyyy) GEORGIA ! Tsia!ra ! !Klarsi Klarsi Andaisi Kintsia ! ! ! Zalda ! RUSSIAN FEDERATION Mipareti ! Maraleti ! Sveri ! ! ! Tskaltsminda Sheleuri !Saboloke !Gvria Marmazeti Eltura ! ! !Kemerti ! Didkhevi Black Sea ! Ortevi ! GEORGIA Tbilisi Kekhvi Tliakana ! ! \ ! Dzartsemi Guchmasta ! ! Marmazeti Khoshuri ! Satskheneti ! ! ! ! Beloti Jojiani Khaduriantkari ! Zemo Zoknari Rustavi ! ! Kurta Snekvi AZERBAIJAN ! Vaneti ! Chachinagi Dzari Zemo Monasteri ! TURKEY ! ! ! Kvemo Zoknari Mamita ! ARMENIA Brili ! ! Brili Zemo Kornisi ! Zemo Tsorbisi ! ! Mebrune ! !Zemo Achabeti ! ! Dmenisi Snekvi Kokhati ! ! Zemo Dodoti Dampaleti Zemo Sarabuk!i Tsorbisi ! ! ! ! Charebi Kvemo Achabeti ! Vakhtana ! Kheiti ! Kverneti ! Didi Tsitskhiata! Patara TsikhiataBekmeri Kvemo Dodoti ! ! ! ! Satakhari ! Legend Bekmari Zemo Ambreti Didi Tsikhiata ! ! !Dmenisi ! Kvasatal!i Naniauri ! ! Eredvi ! Lisa Zemo Ambreti SS OO UU TT HH OO SS SS EE TT II AA ! ! ! Ksuisi assisted Khodabula ! Number of Households !Mukhauri ! !Nagutni Zardiantkari ! Berula ! !Kusireti !Malda !Tibilaani !Argvitsi Teregvani !Galaunta ! !Khelchua Zem! o Prisi Zemo D!zagina Kvemo Nanadakevi ! Disevi ! ! Pichvigvina Zemo Dzagvina ! ! 01 - 250 ! ! Kroz! a Akhalsheni ! Tbeti Arbo ! 251 - 500 ! Arkneti ! Tamarasheni ! Mereti Kulbiti Sadjvare ! ! ! Koshka Beridjvari -

Pdf | 406.42 Kb

! GEORGIA: Newly installed cattle water troughs in Shida Kartli region ! ! Geri ! !Tsiara Klarsi ! Klarsi Andaisi Kintsia ! ! ! Zalda RUSSIAN FEDERATION ! !Mipareti Maraleti Sveri ! I ! Tskaltsminda ! Sheleuri ! Saboloke V ! H Gvria K ! A AG Marmazeti Eltura I M Didkhevi ! ! L Kemerti ! O ! A SA Didkhevi V ! Ortevi R L ! A E Kekhvi Tliakana T Black Sea T'bilisi ! Dzartsemi ! Guchmasta A T ! ! Marmazeti Khoshuri ! ! ! P ! Beloti F ! Tsilori Satskheneti Atsriskhevi ! !\ R Jojiani ! ! ! O Rustavi ! Zemo Zoknari ! N Kurta Snekvi Chachinagi Dzari Zemo Monasteri ! Vaneti ! ! ! ! ! Kvemo Zoknari E Brili Mamita ! ! ! Isroliskhevi AZERBAIJAN !Kvemo Monasteri ! !Brili Zemo Tsorbisi !Zemo Kornisi ! ARMENIA ! Mebrune Zemo Achabeti Kornisi ! ! ! ! Snekvi ! Zemo Dodoti Dampaleti Zemo SarabukiKokhat!i ! Tsorbisi ! ! ! ! TURKEY ! Charebi ! Akhalisa Vakhtana ! Kheiti Benderi ! ! Kverneti ! ! Zemo Vilda P! atara TsikhiataBekmeri Kvemo Dodoti ! NA ! ! ! ! Satakhari REB ULA ! Bekmari Zemo Ambreti Kverne!ti ! Sabatsminda Kvemo Vilda Didi Tsikhiata! ! ! Dmenisi ! ! Kvasatali!Grubela Grubela ! ! ! ! Eredvi ! !Lisa Tormanauli ! ! Ksuisi Legend Khodabula ! Zemo Ambreti ! ! ! ! Berula !Zardiantkari Kusireti ! ! Chaliasubani Malda Tibilaani Arkinareti ! Elevation ! ! Argvitsi ! Teregvani ! Galaunta ! Khelchua ! Zemo Prisi ! ! ! Pirsi Kvemo Nanadakevi Tbeti ! Disevi ! ! ! ! Water trough location m ! ! Zemo Mokhisi ! ! ! Kroza Tbeti Arbo ! !Akhalsheni Arkneti ! Tamarasheni ! ! Mereti ! Sadjvare ! ! ! K ! Khodi Beridjvari Koshka ! -27 - 0 Chrdileti Tskhinvali ! ! -

GEORGIA: UN Security Phases 23 Dec 2008

South Ossetia & Area Adjacent to South Ossetia GEORGIA: UN Security Phases 23 Dec 2008 K K N U Gveleti N ! U ShoviCHAN Glola ! CH ! AK HI LEGEND Tsdo NARI ! I N O International Boundary I R O U HD NI NK MIK MA Resi ! Setepi ! Kazbegi RUSSIANSOUTH OSSETIA FEDERATION ZAKA Phase VI ! Phase III (Area Adjacent to South Ossetia - AA to SO) TE Pansheti R ! G NK ! I Suatisi U ! Toti ! ! ! Tsotsilta Karatkau ! Achkhoti GaiboteniArsha! ! ! S H! City N O Tkarsheti ST ! Mna U ! Garbani S ! ! K A N A GARUL K Sioni L Abano ! I ! ! Sno ! Pkh!elshe Vardisubani Khurtisi ! ! Village Ketrisi ! ! Kvadja U ! N Kanobi ! K ! Shua Kozi Zemo Okrokana ! ! ! Shua Sba Sevardeni ! ! ! Road Network Kvemo Kozi ! Kvemo Okrokana ! !Kvemo Jomaga Nogkau Zemo Roka ! ! Zemo Jomaga Kvemo Sba ! Shua Roka ! Railway Kvedi ! Artkhmo ! Kobi ! Cheliata ! ! Almasiani Ukhati ! ! Leti ! Non-seasonal river Zgubiri Skhanari Kvemo Roka ! ! Kevselta ! Vezuri ! ! A Kabuzta OR Edisa ! Khodzi J ! ! Tsedisi Tamagini JE ! ! ! Bzita Lakes ! Zaseta Kiro!vi ! Nadarbazevi! Chasavali ! Nakreba ! Kvaisi ! Kobeti Akhsagrina ! ! ! Britata Iri ! Sagilzazi ! ! Sheubani ! ! Kvemo Ermani ! Shua Ermani ! PHASE I Shembuli ! Zemo Bakarta Khadisari ! ! Batra Martgajina Kvemo Bakarta ! ! Duodonastro ! ! Litsi Tlia ! Kasagini ! ! Nogkau ! A Zamtareti S Lesora ! Kvemo Machkhara T ! ! A Tlia P ! Tskere Tsarita Palagkau ! ! ! Keshelta !Gudauri Kola ! Mugure Khugata ! !Bajigata ! ! Chagata Shiboita ! Saritata ! ! Kvemo Koshka Benian-Begoni ! ! Biteta !Tsona Vaneli ! ! Samkhret Chifrani Korogo Iukho !Soncho U Muldarta -

GEORGIA: Ethnic Cleansing of Ossetians 1989-1992

Regional Non-Governmental Organisation for the protection and development of national culture and identity of the people of the Republic of North Ossetia and the Republic of South Ossetia «VOZROZHDENIE» - «SANDIDZAN» Profsoyuznaya str., 75-3-174, 117342, Moscow, Russia теl.: +7 (495) 642-3553, e-mail: [email protected] , www.sandidzan.org СОВЕЩАНИЕ 2011 ГОДА ПО ЧЕЛОВЕЧЕСКОМУ ИЗМЕРЕНИЮ В ВАРШАВЕ РАБОЧЕЕ ЗАСЕДАНИЕ 11 Беженцы и перемещенные лица. GEORGIA: Ethnic Cleansing of Ossetians 1989-1992 Inga Kochieva, Alexi Margiev First published in Russia in 2005 by Europe Publishing House as GEORGIA: Ethnic Cleansing of Ossetians ISBN: 5-9739-0030-4 Table of Contents [Main Text] ................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical Index ................................................................................................... 74 Toponymical Reference Table for South Ossetia ...................................................... 78 Introduction As a result of the armed conflict between Georgia and South Ossetia in 1989-1992, a huge part of the Ossetian population in South Ossetia and in Georgia, became refugees, or forcibly displaced people. Significant numbers were forced to resettle in North Ossetia, while the remainder dispersed in Tskhinval and the Ossetian villages of South Ossetia. Since then a plethora of government agencies and non-governmental organisations have wrestled with the refugee problem, but what they have achieved is incommensurate with the -

Mikhail Barabanov, Anton Lavrov, Vyacheslav Tseluyko

Mikhail Barabanov, Anton Lavrov, Vyacheslav Tseluyko The Tanks of August Collected Articles Center for the Analysis of Strategies and Technologies Moscow, 2009 UDK З55.4 BBK 66.4(0) The Tanks of August/М.S. Barabanov, А.V. Lavrov, V.А. Tseluyko; ed. М.S. Barabanov. - М., 2009. - 144 pp. A compendium of articles prepared for the first anniversary of the armed conflict between Russia and Georgia that took place from 8-12 August 2008. The first article is devoted to Georgia's efforts under President Saakashvili to build up its military forces, and it contains a complex description of the basic trends in Georgia's preparations for war. A detailed chronology of military operations is the second and essentially the central body of material. Various sources are drawn upon in its organization and writing - from official chronicles and statements by top ranking figures, to memoirs and the testimony of participants on both sides of the conflict, materials on the Internet. The chronicle provides a detailed review of all the significant combat operations and episodes. The third article in the compendium deals with military development in Georgia in the period after August 2008 and what constitutes the military situation and balance of forces in the Transcaucasus at the present time. The other three articles examine several special aspects of the Five-Day War - losses suffered by Georgian forces in the course of military operations, the losses of Russian aviation in the war; the task of setting up Russian military bases in the territory of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which Russia recognized as independent states. -

Population of the Occupied Territory of Samachablo in the Middle Ages

Karadeniz Uluslararası Bilimsel Dergi Volume: 50, Summer-2021, p. (333-357) ISSN: 1308-6200 DOI Number: https://doi.org/10.17498/kdeniz.947480 Research Article Received: May 3, 2021 | Accepted: June 6, 2021 This article was checked by turnitin. POPULATION OF THE OCCUPIED TERRITORY OF SAMACHABLO IN THE MIDDLE AGES НАСЕЛЕНИЕ ОККУПИРОВАННОЙ ТЕРРИТОРИИ САМАЧАБЛО В СРЕДНЕВЕКОВЬЕ İŞGAL EDİLEN SAMACABLO'NUN ORTAÇAĞDAKİ NÜFUSU ÜZERİNE Giorgi SOSIASHVILI ABSTRACT The significant part of Shida Kartli – Georgia`s historical region has been occupied since the Russo-Georgian August War of 2008. The territory, which was inhabited by the Georgian population from the ancient times and was an integral part of the Georgian area, was turned into South Ossetian Republic by the efforts of the so-called Ossetian separatists and Russian support. The current occupied territories of Didi Liakhvi Gorge were part of Samachablo in the Middle Ages. Samachablo was the feudal land of the representatives of one of the ancient Georgian noble family – the Machabeli. The present work shows the life of Georgians throughout centuries in Samachablo.Traces of population in the Big Liakhvi Gorge can be seen from ancient times, however, there is a lack of statistical data on the exact number of population until the XVIII century. Thus, a comparative analysis of the census ledgers and other documentary material reveal that both, in Tskhinvali and in the villages of the Big Liakhvi Gorge, where the peasants of the Georgian royal family, various noble families and, for the most part, the Machabel feudal house lived, were predominantly Georgians. The Ossetians settled from the North Caucasus in the XVII-XVIII centuries lived only in the mountainous area of Shida Kartli (including the upper part of the Big Liakhvi Gorge). -

Thesis Adviserrecommendation Letter

THESIS ADVISERRECOMMENDATION LETTER This thesis entitled “SOUTH OSSETIA WAR: RUSSIAN FEDERATION DEFENSE POLICY IMPLEMENTATION ON GEORGIA AS RESPONDS TO SOUTH OSSETIA WAR 2008-2009” prepared and submitted by Jonathan Panaluan Damanik in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Art in International Relations in the Faculty of Humanities has been reviewed and found to have satisfied the requirements for a thesis fit to be examined. I therefore recommend this thesis for Oral Defense. Cikarang, Indonesia Recommended and Acknowledged by, Hendra Manurung, SIP., MA. Thesis Adviser i DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that this thesis, entitled “SOUTH OSSETIA WAR: RUSSIAN FEDERATION DEFENSE POLICY IMPLEMENTATION ON GEORGIA AS RESPONDS TO SOUTH OSSETIA WAR 2008-2009” is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, an original piece of work that has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, to another university to obtain a degree. Cikarang, Indonesia, Jonathan Panaluan Damanik ii PANEL OF EXAMINER APPROVAL SHEET The Panel of Examiners declare that the thesis entitled “SOUTH OSSETIA WAR: RUSSIAN FEDERATION DEFENSE POLICY IMPLEMENTATION ON GEORGIA AS RESPONDS TO SOUTH OSSETIA WAR 2008-2009” that was submitted by Jonathan Panaluan Damanik majoring in International Relations from the School of Humanities was assessed and approved to have passed the Oral Examinations on 10 February 2016. Prof. Anak Agung Banyu Perwita, Ph.D. Chair – Panel of Examiners Drs. Teuku Rezasyah, M.A., Ph.D. Examiner Hendra Manurung, SIP., MA. Thesis Adviser iii ABSTRACT South Ossetia War: Russian Federation Defense Policy Implementation on Georgia as Responds to South Ossetia War 2008-2009 2008 was a dark period for South Ossetia. -

The Russian Military and the Georgia War: Lessons and Implications

Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. STRATEGIC STUDIES INSTITUTE The Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) is part of the U.S. Army War College and is the strategic-level study agent for issues related to national security and military strategy with emphasis on geostrate- gic analysis. The mission of SSI is to use independent analysis to conduct strategic studies that develop policy recommendations on: • Strategy, planning, and policy for joint and combined employment of military forces; • Regional strategic appraisals; • The nature of land warfare; • Matters affecting the Army’s future; • The concepts, philosophy, and theory of strategy; and • Other issues of importance to the leadership of the Army. Studies produced by civilian and military analysts concern topics having strategic implications for the Army, the Department of De- fense, and the larger national security community. In addition to its studies, SSI publishes special reports on topics of special or immediate interest. These include edited proceedings of conferences and topically-oriented roundtables, expanded trip re- ports, and quick-reaction responses to senior Army leaders. The Institute provides a valuable analytical capability within the Army to address strategic and other issues in support of Army par- ticipation in national security policy formulation. ERAP Monograph THE RUSSIAN MILITARY AND THE GEORGIA WAR: LESSONS AND IMPLICATIONS Ariel Cohen Robert E. Hamilton June 2011 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the -De partment of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. -

SHIDA KARTLI REGION Reference

SHIDA KARTLI REGION Reference Map 26 March 2009 ! ! ! ! ! ! PA Gviega TS !Barsi! !Jria C Zemo Karzmani ! A Otatikau H ! Nogkau Geri U ILA Kodibina Kulukhta! ! TA ! VIR Kvemo Karzmani Patsa! ! K Tsia!ra Klarsi ! ! Legend ! Patara Gufta ! Klarsi Andaisi Kintsia ! D ! ! Zalda ID ! I L Mipareti H! City/Town I ! Maraleti A ! Itrafisi K ! H !Sveri Tskaltsminda !Sheleuri V ! Saboloke I ! ! Village !Gvria Marmazeti Eltura Kemerti Didkhevi ! ! ! ! Road Network !Didkhevi !Ortevi Kekhvi Tliakana ! ! Dzartsemi ! Guchmasta ! ! Marmazeti ! ! Khoshuri ! ! Beloti ! Tsilori Railway Satskheneti Atsriskhevi ! Ashtauri Jojiani ! ! A ! Zemo Zoknari RUL Rustavi ! ZI ! D !Kurta !Snekvi Chachinagi Dzari Zemo Monasteri !Vaneti ! ! ! !Kvemo Zoknari Non-seasonal river !Mamita !Brili Isroliskhevi Brili !Kvemo Monasteri ! Zemo Kornisi ! Dvaliantkari Zemo Tsorbisi ! ! ! Mebrune Zemo Achabeti Kornisi ! ! ! Ardisi SH ! Dmenisi !Snekvi ! U Zemo Dodoti Dampaleti Zemo SarabukiKokhati! Lakes A Tsorbisi ! ! ! ! F ! R O Charebi N ! Akhalisa E Vakhtana ! Kheiti Benderi ! ! Kverneti ! ! Zemo Vilda ! Bekmeri Kvemo Dodoti ! ! District boundary Didi Tsitskhiata Pata! ra Tsikhiata! ! !Satakhari Bekmari Zemo Ambreti Kvernet!i !Sabatsminda Kvemo Vilda Didi Tsikhiata! ! ! !Dmenisi ! ! Kvasatal!iGrubela Grubela Naniauri ! ! ! Eredvi ! Lisa Tormanauli ! Ksuisi South Ossetia boundary Mukhauri ! Khodabula ! !Zemo Ambreti ! Nagutni ! ! ! Berula Zardiantkari Kusireti ! ! ! Chaliasubani !Koloti Malda Tibilaani Arkinareti ! ! Argvitsi A Teregvani ! Galaunta ! ! ! ! ! Zemo Prisi !Khelchua -

ﻣﺆﲤﺮ ﻧﺰﻉ ﺍﻟﺴﻼﺡ September 2008 15 ARABIC Original: ENGLISH

CD/1850 ﻣﺆﲤﺮ ﻧﺰﻉ ﺍﻟﺴﻼﺡ September 2008 15 ARABIC Original: ENGLISH ﺭﺳﺎﻟﺔ ﻣﺆﺭﺧﺔ ٢٦ ﺁﺏ/ﺃﻏﺴﻄﺲ ٢٠٠٨ ﻣﻮﺟﻬﺔ ﺇﱃ ﺍﻷﻣﲔ ﺍﻟﻌﺎﻡ ﳌﺆﲤﺮ ﻧـﺰﻉ ﺍﻟﺴـﻼﺡ ﻣﻦ ﺍﳌﻤﺜﻞ ﺍﻟﺪﺍﺋﻢ ﳉﻮﺭﺟﻴﺎ ﳛﻴﻞ ﻓﻴﻬﺎ ﻧﺺ ﺍﻟﺘﺤﺪﻳﺚ ﺍﳌﺘﻌﻠﻖ ﺑﺎﳊﺎﻟﺔ ﺍﻟﺮﺍﻫﻨﺔ ﰲ ﺟﻮﺭﺟﻴﺎ ﻳﺸﺮﻓﲏ ﺃﻥ ﺃﺣﻴﻞ ﺇﻟﻴﻜﻢ ﻧﺺ ﺍﻟﺒﻴﺎﻥ ﺍﻟﺬﻱ ﺃﺩﱃ ﺑﻪ ﻭﻓﺪ ﺟﻮﺭﺟﻴﺎ ﰲ ٢٦ ﺁﺏ /ﺃﻏﺴﻄﺲ ٢٠٠٨ ﰲ ﺍﳉﻠـﺴﺔ ﺍﻟﻌﺎﻣﺔ ١١١٥* ﳌﺆﲤﺮ ﻧﺰﻉ ﺍﻟﺴﻼﺡ ﺑﺸﺄﻥ ﺍﻟﻌﺪﻭﺍﻥ ﺍﻟﻌﺴﻜﺮﻱ ﻟﻼﲢﺎﺩ ﺍﻟﺮﻭﺳﻲ ﻋﻠﻰ ﺃﺭﺍﺿﻲ ﺟﻮﺭﺟﻴﺎ، ﺑﺎﻹﺿﺎﻓﺔ ﺇﱃ ﺍﻟﻮﺭﻗﺎﺕ ﺍﳌﺮﻓﻘﺔ ﻃﻴﻪ. ﻭﺃﻛﻮﻥ ﳑﺘﻨﺎﹰ ﻟﻮ ﺃﻣﻜﻨﻜﻢ ﺍﲣﺎﺫ ﺍﻟﺘﺮﺗﻴﺒﺎﺕ ﻹﺻﺪﺍﺭ ﻭ ﺗﻌﻤﻴﻢ ﻧﺺ ﻫﺬﻩ ﺍﻟﺮﺳﺎﻟﺔ، ﺑﺎﻹﺿﺎﻓﺔ ﺇﱃ ﺍﻟﺒﻴـﺎﻥ ﺍﳌﺮﻓـﻖ ﻭﺍﻟﻮﺭﻗﺎﺕ ﺍﳌﺮﻓﻘﺔ ﻃﻴﻪ، ﻛﻮﺛﻴﻘﺔ ﺭﲰﻴﺔ ﻣﻦ ﻭﺛﺎﺋﻖ ﻣﺆﲤﺮ ﻧﺰﻉ ﺍﻟﺴﻼﺡ. (ﺍﻟﺘﻮﻗﻴﻊ): ﺟﻮﺭﺟﻲ ﻏﻮﺭﺟﻴﻼﺩﺯﻩ ﺍﻟﺴﻔﲑ ﺍﳌﻤﺜﻞ ﺍﻟﺪﺍﺋﻢ * ﺍﻧﻈﺮ CD/PV.1115 ﻟﻼﻃﻼﻉ ﻋﻠﻰ ﺍﻟﺒﻴﺎﻥ ﺍﻟﺬﻱ ﺃﺩﱄ ﺑﻪ. (A) GE.08-63119 220908 230908 CD/1850 Page 2 ﻳﻮﺩ ﺍﳌﻤﺜﻞ ﺍﻟﺪﺍﺋﻢ ﳉﻮﺭﺟﻴﺎ، ﺍﻟﺴﻔﲑ ﺟﻮﺭﺟﻲ ﻏﻮﺭﺟﻴﻼﺩﺯﻩ ﺃﻥ ﻳﻨﺘﻬﺰ ﻫﺬﻩ ﺍﳌﻨﺎﺳﺒﺔ ﻹﻃـﻼﻉ ﻣـﺆﲤﺮ ﻧـﺰ ﻉ ﺍﻟﺴﻼﺡ ﺍﳌﻮﻗﺮ ﻋﻠﻰ ﻣﺴﺘﺠﺪﺍﺕ ﺍﳊﺎﻟﺔ ﺍﻟﺮﺍﻫﻨﺔ ﰲ ﺟﻮﺭﺟﻴﺎ، ﻭﻫﻲ ﺍﳊﺎﻟﺔ ﺍﻟﱵ ﺟﺮﻯ ﲝﺜﻬﺎ ﰲ ﺟﻠﺴﺔ ﺍﻷﺳﺒﻮﻉ ﺍﳌﺎﺿﻲ. ﻣﻦ ﺍﻟﻨﺎﺣﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻘﺎﻧﻮﻧﻴﺔ، ﺗﻌﺮﺿﺖ ﺟﻮﺭﺟﻴﺎ ﻟﻌﺪﻭﺍﻥ ﻋﺴﻜﺮﻱ ﺷﺎﻣﻞ ﺷﻨﻪ ﺍﻻﲢﺎﺩ ﺍﻟﺮﻭﺳﻲ ﻣﻨﺘـﻬﻜﺎﹰ ﻣﺒـﺎﺩﺉ ﻭﻗﻮﺍﻋﺪ ﻣﻴﺜﺎﻕ ﺍﻷﻣﻢ ﺍﳌﺘﺤﺪﺓ، ﲟﺎ ﰲ ﺫﻟﻚ ﺣﻈﺮ ﺍﺳﺘﺨﺪﺍﻡ ﺍﻟﻘﻮﺓ ﻓﻴﻤﺎ ﺑﲔ ﺍﻟﺪﻭﻝ ﻭﺍﺣﺘﺮﺍﻡ ﺳﻴﺎﺩﺓ ﺟﻮﺭﺟﻴﺎ ﻭﺳـﻼﻣﺔ ﺃﺭﺍﺿﻴﻬﺎ. ﻭﻣﻦ ﺍﳌﺸﲔ ﺃﻥ ﻳﺴﺘﺨﺪﻡ ﺍﻻﲢﺎﺩ ﺍﻟﺮﻭﺳﻲ ﺍﻻﻧﺘﻬﺎﻙ ﺍﳌﺰﻋﻮﻡ ﳊﻘﻮﻕ ﺍﻷﻭﺳﻴﺘﻴﲔ ﰲ ﺟﻮﺭﺟﻴﺎ ﺫﺭﻳﻌﺔ ﻷﻋﻤﺎﻟﻪ ﻏﲑ ﺍﳌﺸﺮﻭﻋﺔ. ﻭﺟﻮﺭﺟﻴﺎ ﻟﻦ ﲣﻮﺽ ﰲ ﻧﻘﺎﺵ ﺑﺸﺄﻥ ﺍﻷﺳﺒﺎﺏ ﺍﻟﱵ ﺍﺳﺘﻨﺪ ﺇﻟﻴﻬﺎ ﺍﻻﲢﺎﺩ ﺍﻟﺮﻭﺳﻲ ﻟﺘﱪﻳﺮ ﻋﻤﻠﻪ ﺍﻟﻌﺪﻭﺍﱐ، ﻟﻜﻨﻬﺎ ﺗﻜﺘﻔﻲ ﺑ ﺎﻹﺷﺎﺭﺓ ﺇﱃ ﺃﻥ ﺍﺠﻤﻟﺘﻤﻊ ﺍﻟﺪﻭﱄ ﺑﺼﻮﺭﺓ ﻋﺎﻣﺔ ﻻ ﻳﻘﺮ ﺃﻱ ﳉﻮﺀ ﺇﱃ ﺍﺳﺘﺨﺪﺍﻡ ﺍﻟﻘـﻮﺓ ﺑـﺰﻋﻢ "ﲪﺎﻳـﺔ ﺍﳌﻮﺍﻃﻨﲔ/ﺍﻟﻮﻃﻨﻴﲔ ﰲ ﺍﳋﺎﺭﺝ " ﻷﻧﻪ ﻳﺘﻨﺎﰱ ﻣﻊ ﻣﺒﺎﺩﺉ ﻣﻴﺜﺎﻕ ﺍﻷﻣﻢ ﺍﳌﺘﺤﺪﺓ ﻭﻳﻔﺘﻘﺮ ﺇﱃ ﺍﻟﺸﺮﻋﻴﺔ ﺑـﺪﻭﻥ ﺇﺫﻥ ﳎﻠـﺲ ﺍﻷﻣﻦ. ﻭﻣﻦ ﺍﳌﻔﺎﺭﻗ ﺔ ﺃﻥ ﺍﻻﲢﺎﺩ ﺍﻟﺮﻭﺳﻲ ﱂ ﻳﻠﺠﺄ ﻗﻂ ﺇﱃ ﺃﻱ ﺁﻟﻴﺔ ﺩﻭﻟﻴﺔ ﻛﺴﺎﺣﺔ ﻣﻼﺋﻤﺔ ﳌﻨﺎﻗﺸﺔ ﺷﻮﺍﻏﻠﻪ ﺣـﱴ ﻟـﻮ ﺃﻣﻜﻦ ﺍﻟﺰﻋﻢ ﺑﻮﺟﻮﺩ ﻣﱪﺭ ﻣﺸﺮﻭﻉ ﺗﺴﺘﻨﺪ ﺇﻟﻴﻪ ﺣﺠﺔ ﺭﻭﺳﻴﺎ . -

Timeline of Russian Aggression in Georgia in Summer 2008

1. There have been various accounts of the chronology of the conflict in Augusts 2008. What is your understanding of the order in which events took place? Major Hostile Actions by the Russian Federation against Georgia in 2004-2007 GRU Sponsored Terrorist Act in Gori and Sabotage Acts in Shida Kartli Region In 2004-2005, under the cover of the Joint Peacekeeping Forces deployed in the Georgian- Ossetian conflict zone, the Russian special services gathered intelligence and organized subversive/terrorist acts against Georgia. On February 1, 2005, a white “VAZ-2101” type vehicle exploded in front of the building of Shida Kartli regional division of the Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs in Gori. The accident left three police officers dead, more than thirty people wounded, buildings and cars in the vicinity damaged. The investigation conducted by the Counter-Intelligence Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia found out that this terrorist act was prepared and carried out by employees of Russian special services (namely, GRU and FSB) acting under the cover of the Russian peacekeeping battalion of the JPKF and military advisers to the South Ossetian proxy regime: Anatoly Sisoev, GRU Colonel, Military adviser to the South Ossetian de facto president Eduard Kokoity; Mikheil Abramov, Deputy Commander of the Joint Peacekeeping Forces; Roman Boyko, Lieutenant Colonel of the Russian peacekeeping battalion of the JPKF. On October 23 2005, the MIA of Georgia arrested Roman Boyko and later, as a gesture of good will, handed him over to the Russian embassy in Georgia. In 2004, GRU Colonel Anatoly Ivanovich Sisoev was sent to Tskhinvali as an adviser to the de facto president of South Ossetia Eduard Kokoity, where he established a subversive-intelligence unit in the proxy regime’s Ministry of Defense, the so-called “Ossetian GRU,” consisting of up to 120 men, which were sent to North Ossetia and trained by Russian military instructors in subversive activities on the ground of the 58th Russian Army.