Delicate Urbanism in Context: Settlement Nucleation in Pre-Roman Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressemitteilung Als

MINISTERIUM FÜR WISSENSCHAFT, FORSCHUNG UND KUNST PRESSE- UND ÖFFENTLICHKEITSARBEIT PRESSEMITTEILUNG 10. Juli 2020 Nr. 078/2020 Meilensteine für Keltenkonzeption Baden-Württemberg Kunststaatssekretärin Petra Olschowski: „Wir wollen spannende Geschichten erzählen von einer längst vergangenen Zeit, deren oft geheimnisvolle Spuren im ganzen Land zu entdecken sind.“ Die ersten fünf Hotspots stehen jetzt fest – Trichtinger Silberring ist Symbol und Logo des Keltenlandes Das Keltenland Baden-Württemberg wächst zusammen – es gibt weitere Meilen- steine zu feiern: Das Ministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kunst fördert drei zentrale Fundstätten im Land und der Trichtinger Silberring wird zum Symbol und Logo der Marketingkampagne des „Keltenlandes Baden-Württemberg“. Zu- dem wird das Landesmuseum Württemberg das Schaufenster des Keltenlandes in der Landeshauptstadt. „Das spannende keltische Erbe kann nicht nur an eini- gen zentralen Fundstätten und Museen studiert werden, sondern prägt flächen- übergreifend das ganze Land“, betone Kunststaatssekretärin Petra Olschowski am Freitag (10. Juli) im Landesmuseum Württemberg in Stuttgart. Nach einem Beschluss der Landesregierung von 2019 will das Ministerium in den nächsten Jahren insgesamt 10 Millionen Euro in die Keltenkonzeption des Landes investie- ren. Das Land fördert mit dem Heidengraben, dem Ipf und dem Keltenmuseum Hoch- dorf drei zentrale Keltenstätten mit insgesamt 3 Millionen Euro. Zusammen mit der Heuneburg, einer der bedeutendsten keltischen Fundplätze Europas, und Königstraße 46, 70173 Stuttgart, Telefon 0711 279-3005, Fax 0711 279-3081 E-Mail: [email protected], Internet: http://www.mwk.baden-wuerttemberg.de Seite 2 von 4 dem Landesmuseum Württemberg stehen damit die ersten fünf Hotspots der Kel- tenkonzeption fest. Weitere Förderungen, insbesondere auch im badischen Lan- desteil, sollen folgen. Keltenkonzeption Ein Herzstück des Keltenlandes, die oberhalb der Donau gelegene Heuneburg bei Sigmaringen, wird in den nächsten Jahren zu einer Kelten- und Naturerlebnis- welt ausgebaut. -

Collections MUSEUM of the UNIVERSITY of TÜBINGEN MUT

Collections MUSEUM OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TÜBINGEN MUT www.unimuseum.de Collections OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TÜBINGEN The University of Tübingen, founded in 1477, holds a wealth of outstanding items in its research, teaching and exhibition collections. The treasures of the 65 collections are not merely distinguished because of their age and universal diversity, but also because one can find outstanding single pieces of world- wide importance in this multi-subject university collection, one of the largest in all of Europe. Opportunities emerge from this rich heritage, but also obliga- tions for the university. These include organizing for the care of the collected pieces in a responsible manner. They should be available for research, preserved for generations to come, and last but not least be at the disposal of the University for teaching purposes. The Museum of the University of Tübingen MUT is committed to making the collections more accessible to the general public. While some collections have been maintained and cared for for many years by museum curators, others have often been neglected and nearly forgotten. As a consequence, the Uni- versity founded the MUT as the umbrella organization for all the collections in 2006 and thus created the framework for systematically cataloguing and exhibiting its collections. Since 2010, project seminars of the MUT have also contributed to taking stock of and exhibiting neglected collections. Finally in 2016 a master profile class “Museums + Collections” was established. With this brochure, the University wishes to inform its mem- bers as well as the general public of the enormous diversity of the collections. -

“Celtic” Oppida

“Celtic” Oppida John Collis (Respondent: Greg Woolf) I will start by stating that I do not believe the sites our discussion. So, what sorts of archaeological feat which I am defiling with qualify as “city-states”; ures might we expect for our “city” and “tribal” indeed, in the past I have drawn a contrast between the states? city-states of the Mediterranean littoral and the inland The area with which I am dealing lies mainly “tribal states” of central and northern Gaul. However, within central and northern France, Switzerland, and their inclusion within the ambit of this symposium is Germany west of the Rhine (Collis [1984a-b], [1995a- useful for two reasons. Firstly, if a class of “city-state” bl). This is the area conquered by Julius Caesar in is to be defined, it is necessary to define the character 58-51 B.C.. In his Commentaries he refers on istics with reference to what is, or is not, shared with numerous occasions to “oppida”, sites often of urban similar types of simple state or quasi-state formations. character, and apparently all with some form of Secondly, the written documentary sources are some defences. Some of the sites he mentions are readily what thin, or even non-existent, for these sites; there recognisable as predecessors to Roman and modern fore archaeology must produce much of the data for towns (Fig. 1) - Vesontio (Besançon), Lutetia (Paris), Fig. 1. Sites mentioned by Caesar in the De Bello Galileo. 230 John Collis Durocortorum (Reims), and Avaricum (Bourges) - large size with the Gallic and central European sites while others have been deserted, or failed to develop - (Ulaca is about 80ha). -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-14740-9 — Eurasia at the Dawn of History Edited by Manuel Fernández-Götz , Dirk Krausse Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-14740-9 — Eurasia at the Dawn of History Edited by Manuel Fernández-Götz , Dirk Krausse Index More Information INDEX Abel-Rémusat, J.-P., 183 Egypt in the Axial Age, 183–196 Achaemenid period, 206, 208 elite burials in First Millennium BC China, Achilles, 284 211–222 action theory,10 Near Eastern civilization, 198–209 Aedui,340 tumuli and, 225–237 Aegean ancient economies, 139–146 collapse of royal palaces in, 201 embedded economies, 139–140 Neolithic transition of, 71–72 Mesoamerican, prehispanic highland, Aetolia, 287 141–145 Agade, 100 modern economies and, inaccurate notions of, Agamemnon, 284 141 agathois, 286 substantivist-formalist (primitivist-modernist) debate age of enclosure, 15 on, 140–141 Age of Enlightenment, 195 ancient societies, 158 agency theory,243–244 Andalusia, 76, 77 agents, 250–251 Andes, 165 agglo-control. See social agglomeration-control Angkor, 82, 100 agglomeration, 106–109 Ano Mazaraki-Rakita, 287 agglomérations secondaires,272 Anquetil-Duperron, H., 183 Agios Petros, 282 anthropomorphic igurines, 115 Agni, 341–342 Antiquity,194, 336–337 agora, 281, 286 Apennines, 291, 295 agriculture Apolianka, 117 emergence of, 132 Apollo, 337–338 in Near Eastern civilization, 200 Apollo Daphnephoros, 286 population increase and, 110 Apulia, 295 pre-domestic, 68 Aquitania, 395 Akkadian dynasty,100 Arachaeminid system, 201 Akkadian language, 185, 186 Arcadia, 287 Alaça Höyük, 75 archaeological theory,251 Albegna valley,313–314. See also Etruria Arene Candide, Liguria, 72 Alesia, 345 Argenomagus,339 -

Regionales Entwicklungskonzept

Regionales Entwicklungskonzept LEADER-Bewerbung der Region Mittlere Alb im Förderzeitraum 2014-2020 verabschiedet am 24. September 2014 aktualisiert am 01. Mai 2019 vorgelegt durch Lokale Aktionsgruppe Mittlere Alb Koordination und Redaktion Landratsamt Reutlingen, Kreisamt für nachhaltige Entwicklung mit Unterstützung durch Dagmar B. Schmidt (Prozess-Begleitung) Karima Daniel (Geografin) Regionales Entwicklungskonzept LEADER Seite I Region Mittlere Alb Ansprechpartner für das Regionale Entwicklungskonzept Verein LEADER Mittlere Alb e.V. Vorsitzender: Landrat Thomas Reumann Geschäftsstelle Hauptstraße 41 72525 Münsingen www.leader-alb.de Regionalmanagement Hannes Bartholl Telefon: 07381/402 97-01 Email: [email protected] Elisabeth Markwardt Telefon: 07381/402 97-02 Email: [email protected] Im Text wird bei der Bezeichnung von Personen aus Gründen der besseren Lesbarkeit die männli- che Form verwendet. Gleichwohl sind selbstverständlich beide Geschlechter gleichermaßen ge- meint. Regionales Entwicklungskonzept LEADER Seite II Region Mittlere Alb Inhaltsverzeichnis I. Informationen zur regionalen Partnerschaft im LEADER-Gebiet .................................. 1 I.1 Abgrenzung und Lage des Aktionsgebiets ...................................................................... 1 I.2 Zusammensetzung der Aktionsgruppe und Organisationsstruktur der regionalen Partnerschaft .................................................................................................................. 3 I.3 Einrichtung und Betrieb einer Geschäftsstelle -

(Swabian Alb) Biosphere Reserve

A Case in Point eco.mont - Volume 5, Number 1, June 2013 ISSN 2073-106X print version 43 ISSN 2073-1558 online version: http://epub.oeaw.ac.at/eco.mont Schwäbische Alb (Swabian Alb) Biosphere Reserve Rüdiger Jooß Abstract Profile On 22 March 2008, the Schwäbische Alb Biosphere Reserve (BR) was founded and Protected area designated by UNESCO in May 2009. It was the 15th BR in Germany and the first of its kind in the Land of Baden-Württemberg. UNESCO BR Schwäbische Alb After a brief preparatory process of just three years, there are now 29 towns and municipalities, three administrative districts, two government regions, as well as Mountain range the federal republic of Germany (Bundesanstalt für Immobilienaufgaben) as owner of the former army training ground in Münsingen involved in the BR, which covers Low mountain range 850 km2 and has a population of ca. 150 000. Country Germany Location The low mountain range of the Swabian Alb be- longs to one of the largest karst areas in Germany. In the northeast it continues in the Franconian Alb and towards the southwest in the Swiss Jura. In Baden- Württemberg the Swabian Alb is a characteristic major landscape. For around 100 km, a steep escarpment of the Swabian Alb, the so-called Albtrauf, rises 300 – 400 metres above the foothills in the north. The Albtrauf links into the plateau of the Swabian Alb, which pre- sents a highly varied, crested relief in the north, while mild undulations dominate in the southern part. The Swabian Alb forms the European watershed between Rhine and Danube. -

Downloaded Gung

Kelten-Erlebnis-Pfad Unsere Geschichte neu erleben r 730 730 e Legende l Der Kelten-Erlebnis-Pfad740 i e w s t S Startpunkt S | Start Kelten-Erlebnis-Pfad h c Ausschließlich hier besteht die Möglichkeit, die App e r zu starten. An allen weiteren Stationen ist ein Start b HW1 HW1 der App nicht mehr möglich. G n u e s 720 t k a r A 720 v E Alternativer Start A | Barrierearme Inhalte 730 Albsteig Albsteig - S g t Da die Stationen 4, 5 und 7 nicht barrierearm720 zu rö n h 720 h u erreichen sind, werden die Inhalte an dieser Station m m t h 740 f f nochmals gedoppelt. e e c i l l d d R - - W W 720 730 1 Station 1 | Frühkeltisches Gräberfeld e Aussichtsturm 710 g 700 650 2 Station 2 | Wasser auf der Schwäbischen Alb (geplant) 600 3 Station 3 | Ackerbau und Viehhaltung 4 Station 4 | Siedlung und Gehöft t t l l 720 e e Start d d L 1250 L Informationspavillon 5 e e 710Station 5 | Tor zur Stadt i i s s 710 h Wanderparkplatz h 6 e e LegendeStation700 6 | Handel und Handwerk P Die Brille P "Hochholz" S g 7 Station 7 | Der Weg nach Osten r Hülben c h Richtung Grabenstetten 690 em eg ho 8 iumspazierw Station 8 | WanderwegeMauern und Tore Gasthof 1 ä w bi Fernwanderwege Burrenhof h sc Legende 8 c he LegendeKelten-Erlebnis-Pfad S A Legende lb Fernradwege HW1 710 3 -R Kelten-Erlebnis-PfadWanderwege barrierearm a LegendeWanderwege dw A Wanderwege eg Fernwanderwege 2 Fernwanderwege WanderwegeWanderwegeFernradwege Wander- Albsteig Fernradwege parkplatz 4 FernwanderwegeFernwanderwege Heidengrabenzentrum Aussichtspunkt S FernradwegeFernradwege (geplant) chw -

Heidengraben Grossdenkmal.Pdf

Landesamt für Denkmalpflege im Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart Befund – Rekonstruktion – Touristische Nutzung Keltische Denkmale als Standortfaktoren Herausgegeben von Jörg Bofinger und Stephan M. Heidenreich Archäologische Informationen aus Baden-Württemberg Heft In Erinnerung an Jörg Biel (–), Ausgräber am Heidengraben Inhalt Vorwort Jörg Bonger Sehnsucht nach Rekonstruktion und archäologische Realität – einige Gedanken zur „wiederaufgebauten Vergangenheit“ Ines Balzer „Macht hoch die Tür…“. Zugänge und Torbauten in der keltischen Eisenzeit Gerd Stegmaier/ Der Heidengraben – Ein Großdenkmal Frieder Klein auf der Schwäbischen Alb Ines Balzer In die Zange genommen. Das Tor G des Oppidums Heidengraben auf der Schwäbischen Alb Andrea Zeeb-Lanz Tore, Mauern, Wallprofile. Möglichkeiten der Rekonstruktion keltischer Oppidum-Architektur am Beispiel des Donnersberges (Nordpfalz) Thomas Fritsch Forschung – Natur – Tourismus. Zur Nutzungsstrategie von Denkmal und Keltenpark am Ringwall von Otzenhausen, Krs. St. Wendel, Saarland ¡ Michael M. Rind Archäologiepark Altmühltal: Konzept – Befund – Rekonstruktion – Touristische Inwertsetzung ¡¡ Vera Rupp Die Keltenwelt am Glauberg – Vom rekonstruierten Grabhügel zum Archäologischen Park und Museum ¡ Wolfgang F. A. Lobisser Vergangenheit zum „Begreifen“: Die experimental- archäologische Errichtung von latènezeitlichen Hausmodellen und archäologische Großveran- staltungen in der spätkeltischen Siedlung am Burgberg in Schwarzenbach in Niederösterreich ¡¦ Manfred Waßner Das Biosphärengebiet Schwäbische -

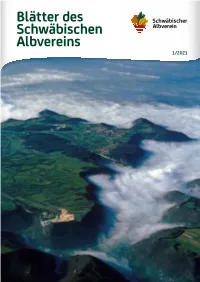

1/2021 Klaus-Peter Kappest

Blätter des Schwäbischen Albvereins 1/2021 Klaus-Peter Kappest Spendenaufruf! Der Schwäbische Albverein als Solidargemeinschaft Die Corona-Pandemie stellt uns alle vor große Herausforde- Wir müssen alle zusammenstehen – WIR, der Schwäbische rungen. Gastronomie und Hotellerie sind erneut geschlossen, Albverein, als große Solidargemeinschaft. Veranstaltungen abgesagt, Kontakte auf ein Minimum reduziert. Das WIR ist jetzt das was zählt! Auch unsere Wanderheime und Türme sind davon betroffen. Damit der Schwäbische Albverein die Wanderheime und Türme Einnahmen für Pächter, Ortsgruppen und Betreuungsvereine sind weiterhin für Gäste offen und attraktiv halten kann, brauchen wir weggebrochen. Mit viel Phantasie und großer Mühe wurde nach Ihre Mithilfe! Einkommensmöglichkeiten gesucht, etwa Essen zum Mitnehmen Es stehen verschiedene Baumaßnahmen an: So müssen unter angeboten. Dennoch sind die Verluste groß. Der Schwäbische anderem die Fassaden des Schönbergturms in Pfullingen und Albverein tut alles, um seinen Pächtern entgegenzukommen, hat der Hohen Warte in St. Johann saniert werden. An der Bolberg- Pachten gestundet und sucht nach weiteren Möglichkeiten zu hel- schutzhütte in Willmandingen gibt es einiges zu reparieren. Im fen. Doch auch wir als Schwäbischer Albverein e. V. mit über 130 Franz-Keller-Haus muss der Eingangsbereich saniert werden und Jahren Bestand haben durch die Krise große finanzielle Einbußen. im Pfannentalhaus wird eine neue Heizung benötigt. Das Roß- Auch gehen die Mitgliederzahlen weiter zurück. In dieser schwe- berghaus erhält außerdem eine Komplettsanierung (Innenraum, ren Zeit heißt es zusammenrücken, sich gegenseitig helfen und Kühltheke etc.), damit noch in diesem Jahr ein neuer Pächter unterstützen. starten kann. Helfen Sie mit, unsere Wanderheime und Türme in Schuss zu halten! Unterstützen Sie uns jetzt mit Ihrer Spende unter dem Stichwort: »SAV als Solidargemeinschaft«. -

LCSH Section H

H (The sound) H.P. 15 (Bomber) Giha (African people) [P235.5] USE Handley Page V/1500 (Bomber) Ikiha (African people) BT Consonants H.P. 42 (Transport plane) Kiha (African people) Phonetics USE Handley Page H.P. 42 (Transport plane) Waha (African people) H-2 locus H.P. 80 (Jet bomber) BT Ethnology—Tanzania UF H-2 system USE Victor (Jet bomber) Hāʾ (The Arabic letter) BT Immunogenetics H.P. 115 (Supersonic plane) BT Arabic alphabet H 2 regions (Astrophysics) USE Handley Page 115 (Supersonic plane) HA 132 Site (Niederzier, Germany) USE H II regions (Astrophysics) H.P.11 (Bomber) USE Hambach 132 Site (Niederzier, Germany) H-2 system USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) HA 500 Site (Niederzier, Germany) USE H-2 locus H.P.12 (Bomber) USE Hambach 500 Site (Niederzier, Germany) H-8 (Computer) USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) HA 512 Site (Niederzier, Germany) USE Heathkit H-8 (Computer) H.P.50 (Bomber) USE Hambach 512 Site (Niederzier, Germany) H-19 (Military transport helicopter) USE Handley Page Heyford (Bomber) HA 516 Site (Niederzier, Germany) USE Chickasaw (Military transport helicopter) H.P. Sutton House (McCook, Neb.) USE Hambach 516 Site (Niederzier, Germany) H-34 Choctaw (Military transport helicopter) USE Sutton House (McCook, Neb.) Ha-erh-pin chih Tʻung-chiang kung lu (China) USE Choctaw (Military transport helicopter) H.R. 10 plans USE Ha Tʻung kung lu (China) H-43 (Military transport helicopter) (Not Subd Geog) USE Keogh plans Ha family (Not Subd Geog) UF Huskie (Military transport helicopter) H.R.D. motorcycle Ha ʻIvri (The Hebrew word) Kaman H-43 Huskie (Military transport USE Vincent H.R.D. -

Urbanization in Iron Age Europe: Trajectories, Patterns, and Social Dynamics

J Archaeol Res DOI 10.1007/s10814-017-9107-1 Urbanization in Iron Age Europe: Trajectories, Patterns, and Social Dynamics Manuel Ferna´ndez-Go¨tz1 Ó The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract The development of the first urban centers is one of the most fundamental phenomena in the history of temperate Europe. New research demonstrates that the earliest cities developed north of the Alps between the sixth and fifth centuries BC as a consequence of processes of demographic growth, hierarchization, and cen- tralization that have their roots in the immediately preceding period. However, this was an ephemeral urban phenomenon, which was followed by a period of crisis characterized by the abandonment of major centers and the return to more decen- tralized settlement patterns. A new trend toward urbanization occurred in the third and second centuries BC with the appearance of supra-local sanctuaries, open agglomerations, and finally the fortified oppida. Late Iron Age settlement patterns and urban trajectories were much more complex than traditionally thought and included manifold interrelations between open and fortified sites. Political and religious aspects played a key role in the development of central places, and in many cases the oppida were established on locations that already had a sacred character as places for rituals and assemblies. The Roman conquest largely brought to an end Iron Age urbanization processes, but with heterogeneous results of both abandon- ment and disruption and also continuity and integration. Keywords Urbanization Á Temperate Europe Á Iron Age Á Fu¨rstensitze Á Open settlements Á Oppida & Manuel Ferna´ndez-Go¨tz [email protected] 1 School of History, Classics and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh, William Robertson Wing, Old Medical School, Teviot Place, Edinburgh EH8 9AG, UK 123 J Archaeol Res Introduction The first millennium BC was a time of urbanization across Eurasia (Ferna´ndez-Go¨tz and Krausse 2016). -

1 M. Rösch, A. Kleinmann, J. Lechterbeck, M. Sillmann, L. Wick

Prof. Dr. Manfred Rösch Labor für Archäobotanik Landesamt für Denkmalpflege im Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart Fischersteig 9 78343 Hemmenhofen Tel. 07735/93777151 Fax 160 e-mail: [email protected] Schriftenverzeichnis Stand: Januar 2010 Im Druck befindlichen Arbeiten sind nicht aufgeführt. Monographien 2008 (191) M. Rösch, M. Heumüller, Vom Korn der frühen Jahre – Sieben Jahrtausende Ackerbau und Kulturlandschaft. Arch. Inf. Bad.-Württ. 55, Esslingen 2008 (102 S.). 1993 (54) M. Rösch, Botanische Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der Kulturlandschaft am Bodensee. Habilitationsschrift, Innsbruck. 1983 (1) M. Rösch, Geschichte der Nussbaumer Seen (Kt.Thurgau) und ihrer Umgebung seit dem Ausgang der letzten Eiszeit aufgrund quartärbotanischer, stratigraphischer und sedimentologischer Untersuchungen. Mitt. Thurgau. Naturf. Ges. 45, 110 S., Frauenfeld 1983. Beiträge 2010 (216) M. Rösch, A. Kleinmann, J. Lechterbeck, M. Sillmann, L. Wick, A Bell Beaker Site with Wet Preservation from Hegau, South-West Germany: Macrofossil and Pollen Evidence for Land Use. In: 15th Conference of the International Work Group for Palaeoethnobotany Wilhelmshaven 2010, Programme and Abstracts, Terra Nostra 2010/2, 2010, 74. 1 (214) M. Rösch, Zur pflanzlichen Ernährung auf mittelalterlichen Burgen – Die Löffelstelz im südwestdeutschen Kontext. In: Stadtarchiv Mühlacker (Hrsg.), Bettelarm und abgebrannt. Von der Burg Löffelstelz und dem Mittelalter in Mühlacker, Beitr. Zur Geschichte der Stadt Mühlacker 7 (Heidelberg u.a. 2010), 255-263. 2009 (213) M. Rösch, G. Gassmann, G. Wieland, Keltische Montanindustrie im Schwarzwald – eine Spurensuche. In: Kelten am Rhein, Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Congress of Celtic Studies, erster Teil, Archäologie, Ethizität und Romanisierung, Beihefte Bonner Jahrbücher 58,1, 2009, 263-278. (212) M. Rösch, Zur vorgeschichtlichen Besiedlung und Landnutzung im nördlichen schwarzwald aufgrund vegetationsgeschichtlicher Untersuchungen in zwei Karseen.