P"M^Pd Ul Bbisy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

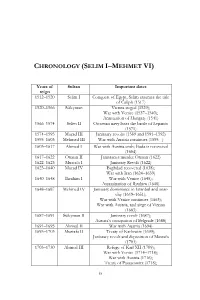

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

1 the Turks and Europe by Gaston Gaillard London: Thomas Murby & Co

THE TURKS AND EUROPE BY GASTON GAILLARD LONDON: THOMAS MURBY & CO. 1 FLEET LANE, E.C. 1921 1 vi CONTENTS PAGES VI. THE TREATY WITH TURKEY: Mustafa Kemal’s Protest—Protests of Ahmed Riza and Galib Kemaly— Protest of the Indian Caliphate Delegation—Survey of the Treaty—The Turkish Press and the Treaty—Jafar Tayar at Adrianople—Operations of the Government Forces against the Nationalists—French Armistice in Cilicia—Mustafa Kemal’s Operations—Greek Operations in Asia Minor— The Ottoman Delegation’s Observations at the Peace Conference—The Allies’ Answer—Greek Operations in Thrace—The Ottoman Government decides to sign the Treaty—Italo-Greek Incident, and Protests of Armenia, Yugo-Slavia, and King Hussein—Signature of the Treaty – 169—271 VII. THE DISMEMBERMENT OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE: 1. The Turco-Armenian Question - 274—304 2. The Pan-Turanian and Pan-Arabian Movements: Origin of Pan-Turanism—The Turks and the Arabs—The Hejaz—The Emir Feisal—The Question of Syria—French Operations in Syria— Restoration of Greater Lebanon—The Arabian World and the Caliphate—The Part played by Islam - 304—356 VIII. THE MOSLEMS OF THE FORMER RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND TURKEY: The Republic of Northern Caucasus—Georgia and Azerbaïjan—The Bolshevists in the Republics of Caucasus and of the Transcaspian Isthmus—Armenians and Moslems - 357—369 IX. TURKEY AND THE SLAVS: Slavs versus Turks—Constantinople and Russia - 370—408 2 THE TURKS AND EUROPE I THE TURKS The peoples who speak the various Turkish dialects and who bear the generic name of Turcomans, or Turco-Tatars, are distributed over huge territories occupying nearly half of Asia and an important part of Eastern Europe. -

The Islamic Question in British Politics

T HE I SLAMIC Q UESTION IN B RITISH P OLITICS AND PRESS DURING THE GREAT WAR. By Shchestyuk Tetyana Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Nadia al-Bagdadi Second Reader: Professor Miklos Lojko CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2013 Abstract The thesis analyzes the role of the Islamic question in British politics and press during the Great War. The connection between British Muslim subjects and the Caliph is defined as the essence of the Islamic question. In the present work the question is considered as a wide- spread idea in British politics, which was referred to as a common point. It is suggested that the Islamic question resulted in two separate developments during the Great War: refuting the Sultan’s call to jihad, and promoting the transfer of the Caliphate to Arabia. The strategies of refuting the Sultan’s call to jihad are analyzed and the stages of the consideration of the idea of the Arab Caliphate in British policy are suggested. Special attention is paid to the year 1917, which witnessed a lack of interest for the Islamic question in the British press, but not in the governmental papers. CEU eTD Collection i Table of Contents List of Illustrations................................................................................................................... iii Introduction................................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Historiographical and Historical Background of the Islamic Question in British Politics......................................................................................................................................11 1.1. Historiographic background of the research.................................................................11 1.1.1. Historiography on the question of Caliphate and pan-Islamism............................11 1.1.2. Islam in relations between Great Britain and Indian Muslims. -

The Influence of Ottoman Empire on the Conservation of the Architectural Heritage in Jerusalem

Indonesian Journal of Islam and Muslim Societies Vol. 10, no. 1 (2020), pp. 127-151, doi : 10.18326/ijims.v10i1. 127-151 The Influence of Ottoman Empire on the conservation of the architectural heritage in Jerusalem Ziad M. Shehada University of Malaya E-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.18326/ijims.v10i1.127-151 Abstract Jerusalem is one of the oldest cities in the world. It was built by the Canaanites in 3000 B.C., became the first Qibla of Muslims and is the third holiest shrine after Mecca and Medina. It is believed to be the only sacred city in the world that is considered historically and spiritually significant to Muslims, Christians, and Jews alike. Since its establishment, the city has been subjected to a series of changes as a result of political, economic and social developments that affected the architectural formation through successive periods from the beginning leading up to the Ottoman Era, which then achieved relative stability. The research aims to examine and review the conservation mechanisms of the architectural buildings during the Ottoman rule in Jerusalem for more than 400 years, and how the Ottoman Sultans contributed to revitalizing and protecting the city from loss and extinction. The researcher followed the historical interpretive method using descriptive analysis based on a literature review and preliminary study to determine Ottoman practices in conserving the historical and the architectural heritage of Jerusalem. The research found that the Ottoman efforts towards conserving the architectural heritage in Jerusalem fell into four categories (Renovation, Restoration, Reconstruction, and Rehabilitation). The Ottomans 127 IJIMS: Indonesian Journal of Islam and Muslim Societies, Volume 10, Number 1, June 2020:127-151 focused on the conservation of the existing buildings rather than new construction because of their respect for the local traditions and holy places. -

Legitimizing the Ottoman Sultanate: a Framework for Historical Analysis

LEGITIMIZING THE OTTOMAN SULTANATE: A FRAMEWORK FOR HISTORICAL ANALYSIS Hakan T. K Harvard University Why Ruled by Them? “Why and how,” asks Norbert Elias, introducing his study on the 18th-century French court, “does the right to exercise broad powers, to make decisions about the lives of millions of people, come to reside for years in the hands of one person, and why do those same people persist in their willingness to abide by the decisions made on their behalf?” Given that it is possible to get rid of monarchs by assassination and, in extreme cases, by a change of dynasty, he goes on to wonder why it never occurred to anyone that it might be possible to abandon the existing form of government, namely the monarchy, entirely.1 The answers to Elias’s questions, which pertain to an era when the state’s absolutism was at its peak, can only be found by exposing the relationship between the ruling authority and its subjects. How the subjects came to accept this situation, and why they continued to accede to its existence, are, in essence, the basic questions to be addressed here with respect to the Ottoman state. One could argue that until the 19th century political consciousness had not yet gone through the necessary secularization process in many parts of the world. This is certainly true, but regarding the Ottoman population there is something else to ponder. The Ottoman state was ruled for Most of the ideas I express here are to be found in the introduction to my doc- toral dissertation (Bamberg, 1997) in considering Ottoman state ceremonies in the 19th century. -

Beylerbeyi Palace

ENGLISH History Beylerbeyi means Grand Seigneur or The present Beylerbeyi Palace was designed Abdülhamid II and Beylerbeyi Palace Governor; the palace and the village were and built under the auspices of the Abdülhamid (1842-1918) ruled the expected from the Western powers named after Beylerbeyi Mehmet Pasha, architects Sarkis Balyan and Agop Balyan BEYLERBeyİ Governor of Rumeli in the reign of Sultan between 1861 and 1865 on the orders of Ottoman Empire from 1876 to without their intrusion into Murad III in the late 16th century. Mehmet Sultan Abdülaziz. 1909. Under his autocratic Ottoman affairs. Subsequently, Pasha built a mansion on this site at that rule, the reform movement he dismissed the Parliament Today Beylerbeyi Palace serves as a palace time, and though it eventually vanished, the of Tanzimat (Reorganization) and suspended the constitution. PALACE museum linked to the National Palaces. name Beylerbeyi lived on. reached its climax and he For the next 30 years, he ruled Located on the Asian shore of the Bosphorus, this splendid adopted a policy of pan- from his seclusion at summer palace is a reflection of the sultan’s interest in The first Beylerbeyi Palace was wooden Islamism in opposition to Yıldız Palace. and was built for Sultan Mahmud II in early western styles of architecture. 19th century. Later the original palace was Western intervention in In 1909, he was deposed shortly abandoned following a fire in the reign of Ottoman affairs. after the Young Turk Revolution, Sultan Abdülaziz built this beautiful 19th of Austria, Shah Nasireddin of Persia, Reza Sultan Abdülmecid. He promulgated the first Ottoman and his brother Mehmed V was century palace on the Asian shore of the Shah Pahlavi, Tsar Nicholas II, and King constitution in 1876, primarily to ward proclaimed as sultan. -

Islam and the Great War in the Middle East, 1914–1918

Journal of the British Academy, 4, 1–20. DOI 10.5871/jba/004.001 Posted 19 January 2016. © The British Academy 2016 Rival jihads: Islam and the Great War in the Middle East, 1914–1918 Elie Kedourie Memorial Lecture read 8 July 2014 EUGENE ROGAN Abstract: The Ottoman Empire, under pressure from its ally Germany, declared a jihad shortly after entering the First World War. The move was calculated to rouse Muslims in the British, French and Russian empires to rebellion. Dismissed at the time and since as a ‘jihad made in Germany’, the Ottoman attempt to turn the Great War into a holy war failed to provoke mass revolt in any part of the Muslim world. Yet, as German Orientalists predicted, the mere threat of such a rebellion, particularly in British India, was enough to force Britain and its allies to divert scarce manpower and materiel away from the main theatre of operations in the Western Front to the Ottoman front. The deepening of Britain’s engagement in the Middle Eastern theatre of war across the four years of World War I can be attributed in large part to combating the threat of jihad. Keywords: Ottoman Empire, Great War, jihad, WWI, Middle East. The Ottoman entry into the First World War should have provoked little or no concern in European capitals. For decades, the West had dismissed the Ottoman Empire as Europe’s sick man.1 Since the late 1870s, the European powers had carved out whole swathes of Ottoman territory for their empires with impunity. The Russians annexed the Caucasian provinces of Kars, Ardahan and Batum in 1878. -

Osmanli Sultani V. Mehmed Reşad'in Vefatinin Ikdam

Uluslararası Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi / The Journal of International Social Research Cilt: 12 Sayı: 65 Ağustos 2019 Volume: 12 Issue: 65 August 2019 www.sosyalarastirmalar.com Issn: 1307 - 9581 Doi Number: http://dx.doi.org/10.17719/jisr.2019.3447 OSMANLI SULTANI V. MEHMED REŞAD'IN VEFATININ İKDAM, SABAH, TANİN VE VAKİT GAZETELERİ'NE YANSIMALARI THE REFLECTI ON OF DEATH OF OTTOMAN SULTAN MEHMED V REŞAD IN THE NEWSPAPERS OF IKDAM, SABAH, TANIN AND VAKI T Nevim TÜZÜN * * Öz Sultan Abdülmecid'in oğlu olan V. Mehmed Reşad, 2 Kasım 1844 tarihinde İstanbul'da dünyaya gelmiştir. Reşad, Ağabeyi II. Abdülhamid'in tahttan indirilmesiyle, 27 Nisan 1909 'da 65 yaşında iken Osmanlı Devleti'nin otuzbeşinci padişahı olarak tahtta çıkmıştır. Padişahlığı sırasında devletin yönetimi kendisinden ziyade İttihat ve Terakki yönetiminin elinde olmuştur. Padişah V. Mehmed Reşad dönemi Osmanlı Devleti'nde büyük buhran ve savaşların yaşandığı bir dönem olmuştur. Zira devletin yıkılışında önemli bir etkiye sahip olan Trablusgarp, Balkan Savaşları ve Birinci Dünya Savaşı onun saltanatı sürecinde cereyan etmiştir. Sultan V. Mehmed Reş ad, Birinci Dünya Savaşı'nın son demlerinin yaşandığı sırada 3 Temmuz 1918 tarihinde şeker hastalığından dolayı 74 yaşında vefat etmiştir. Padişahın vefatı basında da geniş yer bulmuştur. Zira araştırmamıza kaynaklık eden dönemin önde gelen gazetelerinden olan İkdam, Sabah, Tanin ve Vakit Gazeteleri'nin padişahın vefatına geniş yer verdikleri görülmektedir. Mezkûr gazeteler merhum padişahın vefat haberini ilk sayfadan okurları ile paylaşmış, cenaze töreninin her safhasına yer vermişlerdi r. Bununla birlikte incelenen gazetelerden padişahın vefatının sadece Türk basınında değil, müttefik devletlerin basınında da geniş yer bulduğu v e aynı zamanda müttefik devletlerin taziye telgrafları gönderdikleri anlaşılmaktadır. -

Leer Artículo Completo

REAL ACADEMIA MATRITENSE DE HERÁLDICA Y GENEALOGÍA La Casa de Osmán. La sucesión de los Sultanes Otomanos tras la caída del Imperio. Por José María de Francisco Olmos Académico de Número MADRID MMIX José María de Francisco Olmos A raíz de la reciente muerte en Estambul el 23 de septiembre pasado (2009) de Ertugrul Osman V, jefe de la Casa de Osmán o de la Casa Imperial de los Otomanos, parece apropiado hacer unos comentarios sobre esta dinastía turca y musulmana que fue sin duda una de las grandes potencias del mundo moderno. Sus orígenes son medievales y se encuentran en una tribu turca (los ughuz de Kayi) que emigró desde las tierras del Turquestán hacia occidente durante el siglo XII. Su líder, Suleyman, los llevó hasta Anatolia hacia 1225, y su hijo Ertugrul (m.1288) pasó a servir a los gobernantes seljúcidas de la zona, recibiendo a cambio las tierras de Senyud (en Frigia), entrando así en contacto directo con los bizantinos. Osmán, hijo de Ertugrul, fue nombrado Emir por Alaeddin III, sultán seljúcida de Icconium (Konya) y cuando el poder de los seljúcidas de Rum desapareció (1299), Osmán se convirtió en soberano independiente iniciando así la dinastía otomana, o de los turcos osmanlíes. Osmán (m. 1326) y sus descendientes no hicieron sino aumentar su territorio y consolidar su poder en Anatolia. Su hijo Orján (m.1359) conquistó Brussa, a la que convirtió en su capital, organizó la administración, creó moneda propia y reorganizó al ejército (creó el famoso cuerpo de jenízaros), en Brussa construyó un palacio cuya puerta principal se denominaba la Sublime Puerta, nombre que luego se dio al poder imperial otomano hasta su desaparición. -

Teach Ottoman Empire

CMES: Teach Ottoman Empire Grade: 10th&11th Subject: World History (AP) Prepared By: Abbey R. McNair Grade Overview & Purpose Education Standards Addressed The purpose of this unit is to Nebraska state standards: give the world history student an overview of the Ottoman 12.2.2 Students will analyze the patterns of social, economic, political change, Empire. and cultural achievement in the late medieval period. 12.2.7 Students will analyze the scientific, political, and economic changes of the 16th, 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. 12.2.11 Students will demonstrate historical research and geographical skills. APWH (1450-1750): . Changes in trade, technology, and global interactions . Knowledge of major empires and other political units and social systems o Aztec, Inca, Ottoman, China, Portugal, Spain, Russia, France, Britain, Tokugawa, Mughal o Gender and empire (including the role of women in households and in politics) . Slave systems and slave trade . Demographic and environmental changes: diseases, animals, new crops, and comparative population trends . Cultural and intellectual developments Summary of the Ottoman Empire Student prior knowledge: . “Islamic civilization was the third major tradition to evolve after the collapse of the . Byzantine Empire and the Roman Empire in the fourth and fifth centuries. From the seventh through geography of the city of fifteenth centuries, it was arguably the most dynamic and expansive culture in the Constantinople world. Indeed, some scholars have described it as the world's first truly global . Islam as a religion and civilization. Islamic society borrowed much from the Greek, Roman, Persian, and governmental structure Indian traditions and spread them as it extended its reach.”* . -

The Musical Relationship Between England and the Ottoman Empire, Rast Musicology Journal, 7(1), S.1959-1978

RAST MÜZİKOLOJİ DERGİSİ | Yaz Sayısı 2019, 7 (1) Original Research Toker, H. (2019), The musical relationship between England and the Ottoman Empire, Rast Musicology Journal, 7(1), s.1959-1978. Doi:https://doi.org/10.12975/pp1959-1978 The musical relationship between England and the Ottoman Empire* Hikmet Toker Corresponding author: Lecturer of Istanbul University State Conservatory, Musicology Department, İstanbul / Türkiye, [email protected] Abstract This article based on the research project that I conducted at Kings’ College London between 2015-2016. It is titled, The Musical Relationship Between England and the Ottoman Empire. The data that I obtained from the Ottoman and National archives was presented after the analysing process. In this article, the role of music in the relationship between the states and societies is analysed from the time of first diplomatic relationship to the time of the collapse of Ottoman Empire. Additionally, we examined the phenomenon of the use of music as a diplomatic and politic instrument between these countries by specific examples.The main sources of this article were predominantly obtained in the Ottoman Archive, National Archive and British Library. The catalogue numbers of some of them were presented in conclusion, with the thought that they can be used in the future project. Keywords music and politics, ottoman music, musical westernisation, music and diplomacy İngiltere - Osmanlı musiki münasebetleri Özet Bu çalışma 2015-2016 yılları arasında King’s College London’da yürüttüğüm, İngiltere-Osmanlı Müzik Münasebetleri adlı doktora sonrası araştırma projesine dayanmaktadır. Belirtilen sürede Türkiyede ve İngiltere’de yaptığım araştırmalar neticesinde elde edilen bulgular analiz edilerek metin içinde sunulmuştur. -

Freemasonry in Turkey

Extract from World of Freemasonry (2 vols) Bob Nairn FREEMASONRY IN TURKEY Introduction The history of Freemasonry in Turkey is interwoven with its turbulent political history and the gradual decline of the Ottoman Empire, which was a world power during the 18th and 19th centuries and the spiritual and legal centre of the Muslim world. See Appendix A. The decline of the Ottoman Empire was an integral cause of an on-going debate in the Islamic world regarding the role of Muslim law, and, as Muslim Freemasons were directly involved in the political fortunes of the Ottoman Empire, this history is important to an understanding of various Muslim attitudes towards the Craft. Political Change in the Ottoman Empire – 1299-1923 The Ottoman Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries included Anatolia, the Middle East, parts of North Africa, and much of south-eastern Europe to the Caucasus. Constantinople (Istanbul) became the capital of the Ottoman Empire following its capture from the Byzantine Empire in 1453. For a list of the Caliphs of the Ottoman Empire see appendix B. During this period, the Ottoman Empire was among the world's most powerful political entities, with Eastern Europe constantly wary of its steady expansion through the Balkans and the southern part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Its navy was also a powerful force in the Mediterranean. On several occasions, the Ottoman army invaded central Europe, laying siege to Vienna in 1529 and again in 1683, and was only finally repulsed by great coalitions of European powers at sea and on land. It was the only non- European power to seriously challenge the rising power of the West between the 15th and 20th centuries, to such an extent that it became an integral part of European balance-of-power politics.