Discourse on the Significance of Rituals in Religious Socialization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Devotional Literature of the Prophet Muhammad in South Asia

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 Devotional Literature of the Prophet Muhammad in South Asia Zahra F. Syed The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3785 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] DEVOTIONAL LITERATURE OF THE PROPHET MUHAMMAD IN SOUTH ASIA by ZAHRA SYED A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in [program] in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 ZAHRA SYED All Rights Reserved ii Devotional Literature of the Prophet Muhammad in South Asia by Zahra Syed This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Middle Eastern Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. _______________ _________________________________________________ Date Kristina Richardson Thesis Advisor ______________ ________________________________________________ Date Simon Davis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Devotional Literature of the Prophet Muhammad in South Asia by Zahra Syed Advisor: Kristina Richardson Many Sufi poets are known for their literary masterpieces that combine the tropes of love, religion, and the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). In a thorough analysis of these works, readers find that not only were these prominent authors drawing from Sufi ideals to venerate the Prophet, but also outputting significant propositions and arguments that helped maintain the preservation of Islamic values, and rebuild Muslim culture in a South Asian subcontinent that had been in a state of colonization for centuries. -

Persian Manuscripts

A HAND LIST OF PERSIAN MANUSCRIPTS By Sahibzadah Muhammad Abdul Moid Khan Director Rajasthan Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Arabic Persian Research Institute, Tonk RAJASTHAN MAULANA ABUL KALAM AZAD ARABIC PERSIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE RAJASTHAN, TONK 2012 2 RAJASTHAN MAULANA ABUL KALAM AZAD ARABIC PERSIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE RAJASTHAN, TONK All Rights Reserved First Edition, 2012 Price Rs. Published by RAJASTHAN MAULANA ABUL KALAM AZAD ARABIC PERSIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE RAJASTHAN, TONK 304 001 Printed by Navjeevan Printers and Stationers on behalf of Director, MAAPRI, Tonk 3 PREFEACE Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Arabic Persian Research Institute, Rajasthan, Tonk is quenching the thirst of the researchers throughout the world like an oasis in the desert of Rajasthan.The beautiful building of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Arabic and Persian Research Institute Rajasthan, Tonk is situated in the valley of two historical hills of Rasiya and Annapoorna. The Institute is installed with district head quarters at Tonk state Rajasthan in India. The Institute is 100 kms. away at the southern side from the state capital Jaipur. The climate of the area is almost dry. Only bus service is available to approach to Tonk from Jaipur. The area of the Institute‟s premises is 1,26,000 Sq.Ft., main building 7,173 Sq.Ft., and Scholar‟s Guest House is 6,315 Sq.Ft. There are 8 well furnished rooms carrying kitchen, dining hall and visiting hall, available in the Scholar‟s Guest House. This Institute was established by the Government of Rajasthan, which has earned international repute -

Boctor of Pi)!Logopl)P

SOCIO-POLITICAL LIFE IN INDIA DURING 16 th _ 17 th CENTURIES AS REFLECTED IN THE SUFI LITERATURE THESIS ^ SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of pi)!logopl)p HISTORY F ^. BY •/ i KAMAL AKHTAR Under the Supervision of DR. IQBAL SABIR CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2008 ,.:<'M«'U::*^^»>"'S fJtr HI 4.1" '"• Muslim OS^.'-- a V',N^ 2013 •S 'r to^ €i/9eeniA (Dr. IqSaCSaSir Sr. Lecturer CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY Department of History Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh-202002, U.P., India Phone: 0571-2703146(0) Mobile: 09411488564 Dated: 25.11.2008 Certificate This is to certify that Mr. Kamal Akhtar has completed his research work under my supervision. The thesis prepared by him on "Socio political life in India during 16*''-17*'' centuries as reflected in the sufl literature" is his original research work and I consider it suitable for submission for the award of the Degree of Ph.D. in History. (Dr. Iqbal Sabir) Supervisor PREFACE-CUM-ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Sufism has played significant rote in sodat, cuCturaC and even in political' development in India during the medievaC period. H^a^ng aSode in different regions of the country, the MusRm saints, ie. Sufis, attracted people of all sections to their fold. VndouStedCy the motto of Sufis was to develop the feelings of communaC harmony. Cove for human Beings and service ofman^nd. They also left impact on medievaC podticaC Rfe. <But at the same time Sufis and their foCCowers aCso greatCy contriSuted in the fieCd of kaming and schoCarship. -

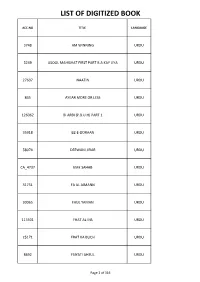

List of Digitized Book

LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK ACC.NO TITLE LANGUAGE 3748 AM WINNING URDU 5249 ASOOL MAHISHAT FIRST PART B.A KAY LIYA URDU 27607 NAATIN URDU 845 AYEAR MORE OR LESS URDU 126062 BI ARBI (P.B.U.H) PART 1 URDU 35918 BZ-E-DORAAN URDU 58074 DEEWANI JIRAR URDU CA_4737 EME SAHAB URDU 31751 FA AL AIMANN URDU 30065 FAUL YAMAN URDU 113501 FHAT AL INS URDU 25171 FRAT KA BUCH URDU 8692 FSIYATI AHSUL URDU Page 1 of 316 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 30138 FSIYAT-I-AFFA URDU 34069 FTAHUL YAMAN URDU 1907 FTAHUL YAMAN BATASHYAT URDU 24124 GAMA-I-TIBISHAZAD URDU 58190 GAMAT UL ASRAR URDU 3509 GD SAKHN URDU 64958 GMA SARMAD URDU 114806 GMAH JAVEED URDU 30328 GMAY ZAR URDU 180689 GSH FIRQAADI URDU 126188 HBZ HAYAT URDU 23817 I AUR PURANI TALEEM URDU 38514 IR G KHAYAL URDU 63302 JANGI AZADI ATHARA SO SATAWAN URDU Page 2 of 316 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 27796 KASH WA KASH URDU 24338 L DAMNIYATI URDU 57853 LAH TASLEEM URDU 5328 MEYATI KEMEYA KI DARSI KITAB URDU 36585 MOD-E-ZINDAGI URDU 113646 MU GAZAL FARSI URDU 1983 PAD MA SHEIKH FARIDIN ATTAR URDU ASL101 PARISIAN GRAMMER URDU 109279 QASH-I-AKHIR URDU 36043 QOOSH MAANI URDU 7085 QOOSHA RANGA RANG URDU 59166 QSH JAWOODAH URDU 38510 QSH WA NIGAAR URDU 23839 RA ZIKIR HUSSAIN(AS) URDU Page 3 of 316 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 456791 SAB ZELI RIYAZI URDU 5374 SEEBIYAT URDU 55986 SHRIYATI MAJID FIRST PART URDU 56652 SIRUL SHQEEN WA GAZLIYAT WA QASAYID URDU 47249 TAIEJ ALZAHAN WAFIZAN AL FIKAR URDU 11195 TAK KHATHA URDU ASL124 TIYA KALAM URDU 109468 VEEN BHARAT URDU CA_4731 WA-E-SHAIDA URDU ASL_286 YA HISAAB URDU 39350 ZAM HIYA HIYA URDU -

Ethnohistory of the Qizilbash in Kabul: Migration, State, and a Shi'a Minority

ETHNOHISTORY OF THE QIZILBASH IN KABUL: MIGRATION, STATE, AND A SHI’A MINORITY Solaiman M. Fazel Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology Indiana University May 2017 i Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Raymond J. DeMallie, PhD __________________________________________ Anya Peterson Royce, PhD __________________________________________ Daniel Suslak, PhD __________________________________________ Devin DeWeese, PhD __________________________________________ Ron Sela, PhD Date of Defense ii For my love Megan for the light of my eyes Tamanah and Sohrab and for my esteemed professors who inspired me iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This historical ethnography of Qizilbash communities in Kabul is the result of a painstaking process of multi-sited archival research, in-person interviews, and collection of empirical data from archival sources, memoirs, and memories of the people who once live/lived and experienced the affects of state-formation in Afghanistan. The origin of my study extends beyond the moment I had to pick a research topic for completion of my doctoral dissertation in the Department of Anthropology, Indiana University. This study grapples with some questions that have occupied my mind since a young age when my parents decided to migrate from Kabul to Los Angeles because of the Soviet-Afghan War of 1980s. I undertook sections of this topic while finishing my Senior Project at UC Santa Barbara and my Master’s thesis at California State University, Fullerton. I can only hope that the questions and analysis offered here reflects my intellectual progress. -

Coke Studio Pakistan: an Ode to Eastern Music with a Western Touch

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Coke Studio Pakistan: An Ode to Eastern Music with a Western Touch SHAHWAR KIBRIA Shahwar Kibria ([email protected]) is a research scholar at the School of Arts and Aesthetics at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Vol. 55, Issue No. 12, 21 Mar, 2020 Since it was first aired in 2008, Coke Studio Pakistan has emerged as an unprecedented musical movement in South Asia. It has revitalised traditional and Eastern classical music of South Asia by incorporating contemporary Western music instrumentation and new-age production elements. Under the religious nationalism of military dictator Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, the production and dissemination of creative arts were curtailed in Pakistan between 1977 and 1988. Incidentally, the censure against artistic and creative practice also coincided with the transnational movement of qawwali art form as prominent qawwals began carrying it outside Pakistan. American audiences were first exposed to qawwali in 1978 when Gulam Farid Sabri and Maqbool Ahmed Sabri performed at New York’s iconic Carnegie Hall. The performance was referred to as the “aural equivalent of the dancing dervishes” in the New York Times (Rockwell 1979). However, it was not until Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s performance at the popular World of Music, Arts and Dance (WOMAD) festival in 1985 in Colchester, England, following his collaboration with Peter Gabriel, that qawwali became evident in the global music cultures. Khan pioneered the fusion of Eastern vocals and Western instrumentation, and such a coming together of different musical elements was witnessed in several albums he worked for subsequently. Some of them include "Mustt Mustt" in 1990 ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 and "Night Song" in 1996 with Canadian musician Michael Brook, the music score for the film The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) and a soundtrack album for the film Dead Man Walking (1996) with Peter Gabriel, and a collaborative project with Eddie Vedder of the rock band Pearl Jam. -

Sufism and Mysticism in Aurangzeb Alamgir's Era Abstract

Global Social Sciences Review (GSSR) Vol. IV, No. II (Spring 2019) | Pages: 378 – 383 49 Sufism and Mysticism in Aurangzeb Alamgir’s Era II). - Faleeha Zehra Kazmi H.O.D, Persian Department, LCWU, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. Assistant Professor, Department of Urdu, GCU, Lahore, Punjab, Farzana Riaz Pakistan. Email: [email protected] Syeda Hira Gilani PhD. Scholar, Persian Department, LCWU, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. Mysticism is defined as a search of God, Spiritual truth and ultimate reality. It is a practice of Abstract religious ideologies, myths, ethics and ecstasies. The Christian mysticism is the practise or theory which is within Christianity. The Jewish mysticism is theosophical, meditative and practical. A school of practice that emphasizes the search for Allah is defined as Islamic mysticism. It is believed that the earliest figure of Sufism is Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). Different Sufis and their writings have http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gssr.2019(IV played an important role in guidance and counselling of people and Key Words: peaceful co-existence in the society. Mughal era was an important period Sufism, Mystic poetry, regarding Sufism in the subcontinent. The Mughal kings were devotees of URL: Mughal dynasty, different Sufi orders and promoted Sufism and Sufi literature. It is said that | Aurangzeb Alamgir was against Sufism, but a lot of Mystic prose and Aurangzeb Alamgir, poetic work can be seen during Aurangzeb Alamgir’s era. In this article, 49 Habib Ullah Hashmi. ). we will discuss Mystic Poetry and Prose of Aurangzeb’s period. I I - Introduction Mysticism or Sufism can be defined as search of God, spiritual truth and ultimate reality. -

Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

All Rights Reserved Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh Book Name: Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh Author: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro Year of Publication: 2018 Layout: Imtiaz Ali Ansari Publisher: Culture and Tourism Department, Government of Sindh, Karachi Printer: New Indus Printing Press Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro Price: Rs.400/- ISBN: 978-969-8100-40-2 Can be had from Culture, Tourism, and Antiquities Department Book shop opposite MPA Hostel Sir Ghulam Hussain Hidaytullah Road Culture and Tourism Department, Karachi-74400 Government of Sindh, Karachi Phone 021-99206073 Dedicated to my mother, Sahib Khatoon (1935-1980) Contents Preface and Acknowledgements 7 Publisher’s Note 9 Introduction 11 1 Prehistoric Circular Tombs in Mol 15 Valley, Sindh-Kohistan 2 Megaliths in Karachi 21 3 Human and Environmental Threats to 33 Chaukhandi tombs and Role of Civil Society 4 Jat Culture 41 5 Camel Art 65 6 Role of Holy Shrines and Spiritual Arts 83 in People’s Education about Mahdism 7 Depiction of Imam Mahdi in Sindhi 97 poetry of Sindh 8 Between Marhi and Math: The Temple 115 of Veer Nath at Rato Kot 9 One Deity, Three Temples: A Typology 129 of Sacred Spaces in Hariyar Village, Tharparkar Illustrations 145 Index 189 8 | Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh | 7 book could not have been possible without the help of many close acquaintances. First of all, I am indebted to Mr. Abdul Hamid Akhund of Endowment Fund Trust for Preservation of the Heritage who provided timely financial support to restore and conduct research on Preface and Acknowledgements megaliths of Thohar Kanarao. -

Asif Ali Khan Qawwali Ensemble

�������������������������� ������� ������ ������������������������ ������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ��������������������������������������� ����������������� ������ �� �� ����� �� �������������� ������������������������������������������������ ������������������������ ���������������������������������������� �������� ���������������������������������������� ������������������������������������� ��������������������������� �������������������� �������������������������� ���������������� ������������������������������� ������������������������������� �����For tickets call toll-free ����������������1–888–CMA–0033 or online at ���������������������������clevelandart.org/performingarts Programs��������� are subject to change. ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������� ������������������������������� ������������������������������� ����������������������������������� ������ ������������������������������������������������ ��������������������� �������������������������� �������������������������������������������� �������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������Asif Ali Khan ��������������������������������������������������������������Qawwali Ensemble Wednesday, March 19, 2014 • 7:30 p.m. ��������������������� ������������������ Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Welcome�������������������������� to the Cleveland -

Knapczyk. Phd Dissertation. Final Draft. 8.20.14

Copyright by Peter Andrew Knapczyk 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Peter Andrew Knapczyk certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Crafting the Cosmopolitan Elegy in North India: Poets, Patrons, and the Urdu Mars̤ iyah , 1707-1857 Committee: Syed Akbar Hyder, Supervisor Rupert Snell Gail Minault Patrick Olivelle Martha Selby Afsar Mohammad Crafting the Cosmopolitan Elegy in North India: Poets, Patrons, and the Urdu Mars̤ iyah , 1707-1857 by Peter Andrew Knapczyk, B.A.; M.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2014 For Kusum Acknowledgements In the course of researching and writing this dissertation, I have incurred innumerable debts of kindness and generosity that I cannot begin to repay, but which I am honored to acknowledge here. To begin, I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Syed Akbar Hyder, whose courses in Urdu literature at UT captivated me early on, and whose unwavering patience and enthusiasm have sustained me to the completion of this project. I am grateful that my time in Austin overlapped with Rupert Snell, whose inspiration and guidance are reflected in the pages of this work. I thank Gail Minault and Patrick Olivelle who have often shared their wisdom with me over the years; their teaching and scholarship are models of excellence to which I aspire. I am also grateful to Martha Selby and Afsar Mohammad for their advice and encouragement. -

Garcin De Tassy the Authors of Hindustani and Their Works

garcin de tassy The Authors of Hindustani and Their Works* [The Biographies] Sanskrit, the language of ancient Aryans, was never the popular language of India, the land of seven rivers, sapta sindhu, as called by the Vedas.1 In plays, this language is placed in the mouths of high-class characters only, while women and the plebeians speak the variants of a dialect called Prakrit (ill-formed) as opposed to Sanskrit (well-formed).2 As the Indians assure us,3 Prakrit, which was always commonly used in Delhi and was * Garcin de Tassyís Les Auteurs Hindoustanis et Leurs Ouvrages díAprès les Biographies Originales (The Hindustani Authors and Their Works, as Described in the Primary Biographies), translated here, mentions a number of individuals by last name only, and several works by abridged titles, making the references unclear at times. The Dictionary of Indian Biography (Buckland 1906) has been very useful in identifying some of the individuals mentioned, especially the European scholars. Similarly, the Catalogue of the Arabic, Persian, and Hindustany Manuscripts (Sprenger 1854) and the History of Hindi Literature (Keay 1920) have been of service in identifying or disambiguating several persons and works cited by de Tassy. Iíve added a subtitle to the opening section as the original appears without one. óTr. (1) Regarding dates, where two years are separated by a slash (/), the first refers to the Islamic calendar and the second to the Common Era, for example: 1221/ 1806–07; where the year stands alone, it is followed by ah or ce, except that ce is not given for years after the thirteenth century ce. -

History Dlsc

Dr. Lakshmaiah IAS Study Circle H. No: 1-10-233, Ashok Nagar, Hyderabad - 500 020. Delhi, Dehradun, Amaravati, Guntur, Tirupati, Vishakhapatnam Ph no:040-27671427/8500 21 8036 HISTORY DLSC Dr. Lakshmaiah IAS Study Circle H. No: 1-10-233, Ashok Nagar, Hyderabad - 500 020. Delhi, Dehradun, Amaravati, Guntur, Tirupati, Vishakhapatnam Ph no:040-27671427/8500 21 8036 CONTENTS CARNATIC MUSIC CLASSICAL DANCE FORMS III. DRAMA, PAINTING AND VISUAL ART IV. Circle HINDUSTANI MUSIC V. IMPORTANT INSTITUTIONS VI. INDIAN ARCHITECTURE VII. INDIAN FAIRS AND FESTIVALSStudy VIII. INDIAN MUSIC IX. LANGUAGES OF INDIA IAS LITERATURE OF INDIA XI. MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS OF INDIA XII. PAINTINGS OF INDIA XIII. PERFORMING ARTS-DRAMA XIV. PUPPET FORMS OF INDIA XV. REGIONAL FOLKS DANCES XVI. RELIGIOUS ISSUES ASSOCIATED WITH CULTURE XVII. SANGAM SOCIETY AND OTHER STUFF Lakshmaiah Dr. 1 . CARNATIC MUSIC The Tamil classic of the 2nd Century AD titled the Silappadhikaram contains a vivid description of the music of that period. The Tolkappiyam, Kalladam & the contributions of the Shaivite and the Vaishnavite saints of the 7th & the 8th Centuries A.D. were also serve as resource material for studying musical history. It is said that South Indian Music, as known today, flourished in Deogiri the capital city of the Yadavas in the middle ages, and after the invasion & the plunder of the city by the Muslims, the entire cultural life of the city took shelter in the Carnatic Empire of Vijaynagar under the reign of Krishnadevaraya. Thereafter, the music of South India came to be known as Carnatic Music. In the field of practical music, South India had a succession of briliant & prolific composers who enriched the art with thousands of compositions.