The Baltic States and Russia Autor(Es)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Please Download Issue 2 2012 Here

A quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. June 2012. Vol. V:2. 1 From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) Academic life in newly Södertörn University, Stockholm founded Baltic States BALTIC WORLDSbalticworlds.com LANGUAGE &GYÖR LITERATUREGY DALOS SOFI OKSANEN STEVE sem-SANDBERG AUGUST STRINDBERG GYÖRGY DALOS SOFI OKSANEN STEVE sem-SANDBERG AUGUST STRINDBERG also in this issue ILL. LARS RODVALDR SIBERIA-EXILES / SOUNDPOETRY / SREBRENICA / HISTORY-WRITING IN BULGARIA / HOMOSEXUAL RIGHTS / RUSSIAN ORPHANAGES articles2 editors’ column Person, myth, and memory. Turbulence The making of Raoul Wallenberg and normality IN auGusT, the 100-year anniversary of seek to explain what it The European spring of Raoul Wallenberg’s birth will be celebrated. is that makes someone 2012 has been turbulent The man with the mission of protect- ready to face extraordinary and far from “normal”, at ing the persecuted Jewish population in challenges; the culture- least when it comes to Hungary in final phases of World War II has theoretical analyzes of certain Western Euro- become one of the most famous Swedes myth, monuments, and pean exemplary states, of the 20th century. There seem to have heroes – here, the use of affected as they are by debt been two decisive factors in Wallenberg’s history and the need for crises, currency concerns, astonishing fame, and both came into play moral exemplars become extraordinary political around the same time, towards the end of themselves the core of the solutions, and growing the 1970s. The Holocaust had suddenly analysis. public support for extremist become the focus of interest for the mass Finally: the historical political parties. -

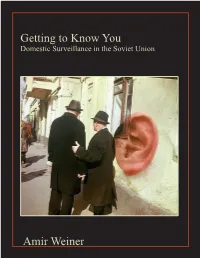

Getting to Know You. the Soviet Surveillance System, 1939-1957

Getting to Know You Domestic Surveillance in the Soviet Union Amir Weiner Forum: The Soviet Order at Home and Abroad, 1939–61 Getting to Know You The Soviet Surveillance System, 1939–57 AMIR WEINER AND AIGI RAHI-TAMM “Violence is the midwife of history,” observed Marx and Engels. One could add that for their Bolshevik pupils, surveillance was the midwife’s guiding hand. Never averse to violence, the Bolsheviks were brutes driven by an idea, and a grandiose one at that. Matched by an entrenched conspiratorial political culture, a Manichean worldview, and a pervasive sense of isolation and siege mentality from within and from without, the drive to mold a new kind of society and individuals through the institutional triad of a nonmarket economy, single-party dictatorship, and mass state terror required a vast information-gathering apparatus. Serving the two fundamental tasks of rooting out and integrating real and imagined enemies of the regime, and molding the population into a new socialist society, Soviet surveillance assumed from the outset a distinctly pervasive, interventionist, and active mode that was translated into myriad institutions, policies, and initiatives. Students of Soviet information systems have focused on two main features—denunciations and public mood reports—and for good reason. Soviet law criminalized the failure to report “treason and counterrevolutionary crimes,” and denunciation was celebrated as the ultimate civic act.1 Whether a “weapon of the weak” used by the otherwise silenced population, a tool by the regime -

The Folklore of Deported Lithuanians Essay by Vsevolod Bashkuev

dislocating literature 15 Illustration: Moa Thelander Moa Illustration: Songs from Siberia The folklore of deported Lithuanians essay by Vsevolod Bashkuev he deportation of populations in the Soviet Union oblast, and the Buryat-Mongolian Autonomous Soviet Social- accommodation-sharing program. Whatever the housing ar- during Stalin’s rule was a devious form of political ist Republic. A year later, in March, April, and May 1949, in rangements, the exiles were in permanent contact with the reprisal, combining retribution (punishment for the wake of Operation Priboi, another 9,633 families, 32,735 local population, working side by side with them at the facto- being disloyal to the regime), elements of social people, were deported from their homeland to remote parts ries and collective farms and engaging in barter; the children engineering (estrangement from the native cultural environ- of the Soviet Union.2 of both exiled and local residents went to the same schools ment and indoctrination in Soviet ideology), and geopolitical The deported Lithuanians were settled in remote regions and attended the same clubs and cultural events. Sometimes imperatives (relocation of disloyal populations away from of the USSR that were suffering from serious labor shortages. mixed marriages were contracted between the exiles and the vulnerable borders). The deportation operations were ac- Typically, applications to hire “new human resources” for local population. companied by the “special settlement” of sparsely populated their production facilities were -

The Commercial Deals Connected with Gazprom's Nord Stream 2

The commercial deals connected with Gazprom's Nord Stream 2 A review of strings and benefits attached to the controversial Russian pipelines Anke Schmidt-Felzmann, PhD Senior Researcher at the Research Centre of the General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania Abstract This paper reviews the multiple strings and benefits attached to the single most controversial gas pipeline project in Europe - the second Russian twin subsea pipeline that is currently under construction in the Baltic Sea. While much attention has been paid to the question of why and how the Russian state- controlled energy giant seeks to circumvent Ukraine as a transit country for its delivery of gas to Western Europe, hardly any attention has been paid to the benefits gained by the companies and political entities directly involved in the preparation and construction of Nord Stream 2. The paper seeks to fill this gap in the debate by taking a closer look at the business deals and commercial actors involved in the implementation of this second Russian natural gas pipeline project in the Baltic Sea. It highlights how local and national economic interests and European energy companies' motivations for participating in the project go beyond the volumes of Russian natural gas that Gazprom expects to deliver to European customers through its Baltic Sea pipelines from 2020. Keywords: Baltic Sea, Nord Stream, Gazprom, Russia, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Latvia. This analysis was produced within the Think Visegrad Non-V4 Fellowship programme. Think Visegrad – V4 Think Tank Platform is a network for structured dialog on issues of strategic regional importance. The network analyses key issues for the Visegrad Group, and provides recommendations to the governments of V4 countries, the annual presidencies of the group, and the International Visegrad Fund. -

The Baltic Sea Region the Baltic Sea Region

TTHEHE BBALALTTICIC SSEAEA RREGIONEGION Cultures,Cultures, Politics,Politics, SocietiesSocieties EditorEditor WitoldWitold MaciejewskiMaciejewski A Baltic University Publication A chronology of the history 7 of the Baltic Sea region Kristian Gerner 800-1250 Vikings; Early state formation and Christianization 800s-1000s Nordic Vikings dominate the Baltic Region 919-1024 The Saxon German Empire 966 Poland becomes Christianized under Mieszko I 988 Kiev Rus adopts Christianity 990s-1000s Denmark Christianized 999 The oldest record on existence of Gdańsk Cities and towns During the Middle Ages cities were small but they grew in number between 1200-1400 with increased trade, often in close proximity to feudal lords and bishops. Lübeck had some 20,000 inhabitants in the 14th and 15th centuries. In many cities around the Baltic Sea, German merchants became very influential. In Swedish cities tensions between Germans and Swedes were common. 1000s Sweden Christianized 1000s-1100s Finland Christianized. Swedish domination established 1025 Boleslaw I crowned King of Poland 1103-1104 A Nordic archbishopric founded in Lund 1143 Lübeck founded (rebuilt 1159 after a fire) 1150s-1220s Denmark dominates the Baltic Region 1161 Visby becomes a “free port” and develops into an important trade center 1100s Copenhagen founded (town charter 1254) 1100s-1200s German movement to the East 1200s Livonia under domination of the Teutonic Order 1200s Estonia and Livonia Christianized 1201 Riga founded by German bishop Albert 1219 Reval/Tallinn founded by Danes ca 1250 -

Leps A. Soviet Power Still Thrives in Estonia

Leps A. ♦ The Soviet power still thrives in Estonia Abstract: It is a historical fact that world powers rule on the fate of small countries. Under process of privatization in the wake of the newly regained independence of Estonia in 1991, a new Estonian elite emerged, who used to be managers of ministries, industries, collective farms and soviet farms. They were in a position to privatize the industrial and agricultural enterprises and they quite naturally became the crème de la crème of the Estonian people, having a lot of power and influence because they had money, knowledge, or special skills. They became capitalists, while the status of the Soviet-time salaried workers remained vastly unchanged: now they just had to report to the nouveaux riches, who instituted the principles of pre-voting (a run-up to the election proper) and electronic voting, to be able to consolidate their gains. However those principles are concepts, unknown to the basic law (Constitution) of the Republic of Estonia – hence the last elections of the 13th composition of the Parliament held in 2015 are null and void ab initio. Keywords: elite of the Republic of Estonia; deportation; „every kitchen maid can govern the state“; industry; agriculture; banking; privatisation; basic law of the Republic of Estonia (Constitution); pre-voting; electronic voting. How they did the Republic of Estonia in It is a very sad story in a nutshell, evolving from 1939, when events and changes started to happen in Europe, having important effects on Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania that couldn’t be stopped. Two major European powers - Germany and the Soviet Union reared their ugly heads and, as had invariably happened in the past, took to deciding on destiny of the small states. -

5G Development in the Baltic States

NATO cyber experts have called 5G the ‘digital four frequencies but has endured criticism from nervous system of the contemporary societies.’1 Elisa Eesti, Tele2 Eesti, and Telia Eesti, the three But with the increased connectivity offered by largest operators in Estonia who claim the 5G, however, comes an exponential rise in the reduced frequency bands are too small to number of potential targets for espionage. The support a stable 5G network.4 Baltic states have begun to heed the warnings of Latvia is one of the first countries to push out a their principal ally, the United States, who is 5G network, and ranks third in Europe for 5G calling to end cooperation with the Chinese readiness.5 Its largest operator Latvijas Mobilais telecom giant Huawei. The governments of the Telefons (LMT) established the first working 5G Baltic states are discovering that road to 5G base in Riga and, alongside Tele2 Latvija, has built development is becoming increasingly complex 5G base stations that offer mobile users access to and fraught with geopolitical and national the 5G network. Bite Latvija, Latvia’s third largest security considerations. operator, is still testing. Latvia hosted their first 5G frequency auction in December of 2017, at which the 3.4-3.8GHz frequencies were auctioned off to LMT. Both Tele2 and Bite have since also acquired spectrum frequencies and in The Baltic region has been dubbed a ‘poster child’ June of 2019, agreed to merge networks in Latvia for early cases of 5G use due to the region’s and Lithuania.6 recent history of technological innovation. -

The Deportation Operation “Priboi” in 1949

The deporTaTion operaTion “priboi” in 1949 Aigi RAhi-TAmm, AndRes KAhAR The operation known as the 1949 deportations materials from6 Russian archives have been of con- was the most massive violent undertaking carried siderable use. out by the Soviet authorities simultaneously in all three Baltic states. The planning of deporTaTions Deportations have been fairly1 thoroughly dealt with in Estonian historiography. It is not unequivocally clear even today when or 2 by whom the idea of a large deportations operation Lists of the deportees have been published; the in the Baltic states was first mentioned. The neces- timeline of events has been documented, as well sity of deportations had been mentioned both in as the individuals and institutions associated with the context of the sovietisation of agriculture and carrying them out; and3 several autobiographies suppression of the Forest Brothers movement. In have been published. The present study is mostly early 1948, Andrei Zhdanov, Secretary of the Central based on archive records available4 in Estonia and Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet papers published in Estonia. Also the works5 of Union (hereinafter the CPSU CC) received a report Russian, Latvian and Moldovan historians and from the officials who had inspected the situation 1 Aigi Rahi-Tamm, “Nõukogude repressioonide uurimisest Eestis” (On the Study of Soviet Repressions in Estonia) in Eesti NSV aastatel 1940–1953 : Sovetiseerimise mehhanismid ja tagajärjed Nõukogude Liidu ja Ida–Euroopa arengute kontekstis (Estonian SSR in 1940–1953 : the Mechanisms and Consequences of Sovietisation in the Context of Developments in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe), compiled by T. -

Migration and the New Austeriat: the Baltic Model and the Socioeconomic Costs of Neoliberal Austerity

Migration and the new austeriat: the Baltic model and the socioeconomic costs of neoliberal austerity Charles Woolfson (Linköping University, Sweden) Jeffrey Sommers (University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee) Arunas Juska (East Carolina University) W.I.R.E. Workshop on Immigration, Race, and Ethnicity Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at the Harvard Kennedy School 24 February 2015 Abstract The Great Economic Recession was experienced with particular severity in the peripheral newer European Union member states. Baltic governments in particular introduced programmes of harsh austerity known as ‘internal devaluation’. The paper argues that austerity measures have accelerated the fragmentation of the labour market into a differentially advantaged primary (largely public) sector, and an increasingly ‘informalized’ secondary (largely low-skill manufacturing and services) sector. It is suggested that the production of a segmented labour market has acted as a major stimulus towards creating, in both Latvia and Lithuania, among the highest levels of emigration in the European Union, especially during the years of the crisis from 2008 onwards. In the absence of effective state policy to address a gathering socio-demographic crisis in which this migration is a key component, so-called ‘free movement’ of labour raises troubling questions for wider societal sustainability in the European Union’s neoliberal semi- periphery in an era of protracted austerity. Keywords: Austerity, crisis, migration, Lithuania, labour market segmentation, neoliberalism, informalisation, European periphery Introduction The onset of the global economic crisis has led to a dramatic increase of emigration from a number of East European countries that have become members of the European Union (EU) (Galgóczi, Leschke, and Watt 2012). -

Sinteză Ştiri Presă Internaţională 1 August

Serviciul Comunicare și Relații Publice SINTEZĂ ŞTIRI PRESĂ INTERNAŢIONALĂ realizată cu sprijinul consilierilor economici din rețeaua externă 1 AUGUST 2019 COREEA 1. Yonhap News Agency (online): Titlu: Japan likely to pass bill striking S. Korea off export whitelist: ministry Rezumat: Japonia va adopta un proiect de lege săptămâna aceasta pentru a elimina Coreea din „lista sa albă” de parteneri comerciali de încredere. Este de asteptat ca proiectul de lege să fie aprobat în cadrul unei ședințe a Cabinetului și va fi supus procedurilor de rigoare înainte de a intra în vigoare la sfârșitul lunii august. Ministerul de externe a declarat că intenționează să transmită un mesaj către Tokyo subliniind nedreptatea mișcării sale de a exclude Seoulul din lista albă și de a-și exprima regretul profund, dacă aprobă proiectul de lege. Kang a mai spus că echipa ei lucrează pentru a organiza discuții bilaterale separate cu omologii săi din SUA și Japonia - Mike Pompeo și Taro Kono - pe marginea Forumului regional ASEAN care va avea loc în Thailanda la sfârșitul acestei săptămâni, și este foarte probabil ca întâlnirile să aibă loc. 2. Yonhap News Agency (online): Titlu: Gov't seeks labor law revisions for parliamentary ratification of key ILO conventions Rezumat: Guvernul a declarat marți, 30 iulie 2019, că intenționează să efectueze o revizuire a legilor muncii într-un mod care să consolideze dreptul sindical al lucrătorilor, urmărind ratificarea parlamentară a standardelor internaționale în domeniu. Ministerul Muncii a declarat anterior că va prezenta parlamentului o moțiune pentru a solicita aprobarea parlamentară a trei din cele patru convenții cheie ale Organizației Internaționale a Muncii (OIM), împreună cu eforturile de revizuire a legilor conexe. -

I ESCALATION in the BALTICS: an OVERVIEW of RUSSIAN INTENT Author-Joseph M. Hays Jr. United States Air Force Submitted in Fulfil

ESCALATION IN THE BALTICS: AN OVERVIEW OF RUSSIAN INTENT Author-Joseph M. Hays Jr. United States Air Force Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for AIR UNIVERSITY ADVANCED RESEARCH (NEXT GENERATION INTELLIGENCE, SURVEILLANCE, AND RECONNAISSANCE) in part of SQUADRON OFFICER SCHOOL VIRTUAL – IN RESIDENCE AIR UNIVERSITY MAXWELL AIR FORCE BASE December 2020 Advisor: Ronald Prince ISR 200 Course Director Curtis E. LeMay Center i THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK ii ABSTRACT Russia poses a significant threat to the Baltics. Through hybrid warfare means, Russia has set the stage for invasion and occupation in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. This paper begins with an exploration of the motivations and history Russia has for occupying the Baltics by primarily addressing the issues of energy dominance and the Baltics’ precedence for insurgency. The Baltic states have whole-of-nation defense strategies in conjunction with NATO interoperability which should most likely deter a full-scale invasion on the part of Russia, despite Russia possessing military superiority. However, Russia has a history of sewing dissent through information operations. This paper addresses how Russia could theoretically occupy an ethnically Russian city of a Baltic country and explores what measures Russia may take to hold onto that territory. Specifically as it pertains to a nuclear response, Russia may invoke an “escalate to de-escalate” strategy, threatening nuclear war with intermediate-range warheads. This escalation would take place through lose interpretation of Russian doctrine and policy that is supposedly designed to protect the very existence of the Russian state. This paper concludes by discussing ways forward with research, specifically addressing NATO’s full spectrum of response to Russia’s escalation through hybrid warfare. -

Dangerous Brinkmanship: Close Military Encounters Between Russia and the West in 2014

November 2014 Policy brief Dangerous Brinkmanship: Close Military Encounters Between Russia and the West in 2014 Thomas Frear Łukasz Kulesa Ian Kearns EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Since the Russian annexation of Crimea, the intensity and gravity of incidents involving Rus- sian and Western militaries and security agencies has visibly increased. This ELN Policy Brief provides details of almost 40 specific incidents that have occurred over the last eight months (an interactive map is available here). These events add up to a highly disturbing picture of violations of national airspace, emergency scrambles, narrowly avoided mid-air collisions, close encounters at sea, simulated attack runs and other dangerous actions hap- pening on a regular basis over a very wide geographical area. Apart from routine or near-routine encounters, the Brief identifies 11 serious incidents of a more aggressive or unusually provocative nature, bringing a higher level risk of escalation. These include harassment of reconnaissance planes, close overflights over warships, and Russian ‘mock bombing raid’ missions. It also singles out 3 high risk incidents which in our view carried a high probability of causing casualties or a direct military confrontation: a nar- rowly avoided collision between a civilian airliner and Russian surveillance plane, abduction of an Estonian intelligence officer, and a large-scale Swedish ‘submarine hunt’. Even though direct military confrontation has been avoided so far, the mix of more aggres- sive Russian posturing and the readiness of Western forces to show resolve increases the risk of unintended escalation and the danger of losing control over events. This Brief there- fore makes three main recommendations: 1.