The Naming Game: the Politics of Place Names As Tools for Urban Regenerative Practice?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Tracking List Edition January 2021

AN ISENTIA COMPANY Australia Media Tracking List Edition January 2021 The coverage listed in this document is correct at the time of printing. Slice Media reserves the right to change coverage monitored at any time without notification. National National AFR Weekend Australian Financial Review The Australian The Saturday Paper Weekend Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 2/89 2021 Capital City Daily ACT Canberra Times Sunday Canberra Times NSW Daily Telegraph Sun-Herald(Sydney) Sunday Telegraph (Sydney) Sydney Morning Herald NT Northern Territory News Sunday Territorian (Darwin) QLD Courier Mail Sunday Mail (Brisbane) SA Advertiser (Adelaide) Sunday Mail (Adel) 1st ed. TAS Mercury (Hobart) Sunday Tasmanian VIC Age Herald Sun (Melbourne) Sunday Age Sunday Herald Sun (Melbourne) The Saturday Age WA Sunday Times (Perth) The Weekend West West Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 3/89 2021 Suburban National Messenger ACT Canberra City News Northside Chronicle (Canberra) NSW Auburn Review Pictorial Bankstown - Canterbury Torch Blacktown Advocate Camden Advertiser Campbelltown-Macarthur Advertiser Canterbury-Bankstown Express CENTRAL Central Coast Express - Gosford City Hub District Reporter Camden Eastern Suburbs Spectator Emu & Leonay Gazette Fairfield Advance Fairfield City Champion Galston & District Community News Glenmore Gazette Hills District Independent Hills Shire Times Hills to Hawkesbury Hornsby Advocate Inner West Courier Inner West Independent Inner West Times Jordan Springs Gazette Liverpool -

Annual Report FY14

RENEW ADELAIDE ANNUAL REPORT (FY / 14) A LETTER FROM CHAIRPERSON STEVE MARAS & GENERAL MANAGER LILY JACOBS Put simply, it has been an incredible year for The challenges we took on and successes we Renew Adelaide. In fact, it has been a had over the last year are huge. tremendous journey for Renew overall. I I was excited to see so many projects get off am enormously proud of everyone who has the ground, to see the amazing ideas that worked to bring the organisation to where it people have and the energy they bring. And is today – the volunteer board, our opera- such diversity – studio, retail, theatre , small tions team and all the pro bono and volun- bars and galleries; all unique ideas that teer supporters. contribute to the personalised and boutique This last financial year saw the superb experience that defines interesting places. outcomes of all the hard and great work There were many amazing examples. It took that’s been put in - the activation results us 9 months to get through some of the tripled fom the previous year and we regulatory and building issues to bring worked with 30 different projects across the Ancient World to life – and it has now CBD and Port Adelaide. We witnessed 11 become an amazing new small bar and new property owners become involved with cultural destination. We worked with the the program as they saw the benefits of Central Markets on some creative produce innovative ways in reducing vacancy. retailers, and saw the cultural reinvention of The entrepreneurial and creative spirit is the former Trims building through That well and truly alive in our city. -

Business Source Corporate Plus

Business Source Corporate Plus Other Sources 1 May 2015 (Book / Monograph, Case Study, Conference Papers Collection, Conference Proceedings Collection, Country Report, Financial Report, Government Document, Grey Literature, Industry Report, Law, Market Research Report, Newspaper, Newspaper Column, Newswire, Pamphlet, Report, SWOT Analysis, TV & Radio News Transcript, Working Paper, etc.) Newswires from Associated Press (AP) are also available via Business Source Corporate Plus. All AP newswires are updated several times each day with each story available for accessing for 30 days. *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN / ISBN Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Start Full Text Stop Availability* Abstracting Start Abstracting Stop Newspaper -

Heritage, History and Heartache in the Redevelopment of the Port Adelaide Waterfront, South Australia

15th INTERNATIONAL PLANNING HISTORY SOCIETY CONFERE N C E ‘OUR HARBOUR... THEIR DREAM’: HERITAGE, HISTORY AND HEARTACHE IN THE REDEVELOPMENT OF THE PORT ADELAIDE WATERFRONT, SOUTH AUSTRALIA. DR GERTRUDE E SZILI* DR MATTHEW W ROFE Address: *School of the Environment Flinders University GPO Box 2100, Adelaide 5001 South Australia Australia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Following the demise of the industrial economy, many western cities and their industrial precincts have become synonymous with social, economic and environmental malaise. As a result, recent trends in urban policy have revealed an explicit emphasis on the redevelopment and revitalisation of these underutilised industrial landscapes. Indicative of these landscapes are ports and other neglected waterfront sites. The redevelopment of the Port Adelaide waterfront in South Australia serves as an exemplar of such a post-industrial transformation. Dominated by entrepreneurial governance arrangements, powerful public and private sectors have coalesced to reinvigorate the decaying landscape through physical restructuring and discursive tactics aligned with city marketing and place making campaigns (Szili & Rofe 2007; 2010; 2011;Rofe & Szili 2009). In doing so, images of growth and cosmopolitan vitality supplant the stigmatised images associated with deindustrialisation, portraying the region as once again economically vital and socially progressive. Central to this reimaging is an explicit recognition and engagement with the Port’s maritime history and heritage. Drawing on the successful post-industrial transformation of other waterfronts such as the Melbourne and London docklands (see for example Butler 2007; Dovey 2005; Marshall 2001), the incorporation of heritage-sensitive design in Port Adelaide was not dissimilar to other ports globally. -

South Australia, and Falls Under the City of Port Adelaide Enfield

North Haven South Australia Introducing North Haven 1 | www.capitalwealth.net.au North Haven Table of Contents Welcome to North Haven………..…………..……..3 Map……………………………………………………..4 Demographics……………………………...…………5 Growth……………………………………...……...…..11 Infrastructure…………...……………………...……...13 In the News…………………………………………....19 Education……………..………………….………..….26 Entertainment…………………………..………….....28 2 | North Haven Welcome to North Haven – you will feel you are on holidays every day! North Haven is a north-western suburb of Adelaide, 20 km from the CBD, in the state of South Australia, and falls under the City of Port Adelaide Enfield. It is adjacent to Osborne and Outer Harbor. North Haven has everything for you and for your family. The suburb is served with numerous schools, great restaurants and parks. It is the best spot to exercise in open air: you can enjoy a walk along the beach or stroll around the marina. The marina, lined with exclusive and desirable houses, is protected by two artificial breakwaters. Attached to that is the Cruising Yacht Club of South Australia, one of Adelaide's largest yacht clubs, whilst around the entrance to the Port River lies the Royal South Australian Yacht Squadron. There is also a retirement village on Lady Gowrie Road, and a small shopping Centre on Osborne Road. It is impossible not to love North Haven! 3 | North Haven 4 | North Haven Demographics 5 | North Haven Key Facts: In the 2011 Census, there were 14,058 people in North Haven (Statistical Area Level 2) of these 48.7% were male and 51.3% were female. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people made up 2.8% of the population. -

2310De27bb274909a63468057

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 16 NOVEMBER NSW QLD VIC SA WA EVENT DAY #SnapSydney #SnapBrisbane #SnapMelbourne #SnapAdelaide #SnapPerth START START START START START #SnapAustralia 4,657* 1,729 1,552 910 1,607 Hashtag use END END END END END 8,389* 3,670 4,954 1,667 2,708 % growth 80% 112% 219% 83% 69% (+3,732) (+1,941) (+3,402) (+757) (+1,101) TOTAL NATIONAL POSTS UP 86%, TOTAL POSTS ON THE DAY 10,933 Followers START START START START START (for each state 1,586 343 409 102 288 Snap Instagram page) END END END END END 1,887 590 744 197 352 % growth 19% 72% 82% 93% 19% (+301) (+247) (+335) (+95) (+64) TOTAL NATIONAL FOLLOWERS UP 29%, TOTAL FOLLOWERS ON THE DAY 1,042 *NSW figures based only on 2016. as at 17 Nov. ^TOTAL @SnapSydney followers 1,887 87 TITLES 20 TITLES 26 TITLES 14 TITLES 10 TITLES 17 TITLES NSW VIC QLD SA WA • Blacktown Advocate • Bayside Leader • Albert & Logan News • City North Messenger • Advocate • Canterbury/Bankstown • Caulfield Leader • Caboolture Shire Herald • Coast City Weekly • Canning Times Express • Cranbourne Leader • City North News • East Torrens Messenger • Comment News • Central Coast Express • Diamond Valley Leader • City South News • Eastern Courier Messenger • Eastern Reporter • Central Courier • Frankston Leader • North-West News • Leader Messenger • Fremantle/Cockburn Gazette • Fairfield Advance • Greater Dandenong Leader • Northside Chronicle • Northern Messenger • Guardian Express • Hill Shire Times • Heidleberg Leader • Pine Rivers Press/ North • Portside Messenger • Hills Gazette • Hornsby -

Pontificia Universidad Católica Del Ecuador Facultad De Comunicación Lingüística Y Literatura Escuela Multilingüe De Negocios Y Relaciones Internacionales

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DEL ECUADOR FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIÓN LINGÜÍSTICA Y LITERATURA ESCUELA MULTILINGÜE DE NEGOCIOS Y RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES DISERTACIÓN PREVIA A LA OBTENCIÓN DEL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADO MULTINGÜE EN NEGOCIOS Y RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES ESTADO DEL PODER HEGEMÓNICO DURO Y BLANDO DE ESTADOS UNIDOS EN EL SIGLO XXI STALIN XAVIER TAYUPANTA CÁRDENAS ENERO, 2014 QUITO – ECUADOR A mi familia AGRADECIMIENTOS A mi padre y a mi madre por el infinito amor, apoyo incondicional, comprensión y especialmente tolerancia que me han brindado durante toda la vida y en mi camino hacia la autosuficiencia en este mundo egoísta y competitivo. Ellos serán siempre mi apoyo y mi pilar fundamental para todas las decisiones que emprenda para mi futuro. A mi hermano por su apoyo y sus lecciones tanto académicas como de vida; es muy fácil darse cuenta que tiene un amplio talento ¡Seguramente será un gran economista! A mi directora, Paola Lozada quién hace tres años despertó en mí la vocación de las relaciones internacionales y ahora me ha brindado la oportunidad de dirigir acertadamente esta Disertación de Grado. A mis jefas y amigas, Wendy Barreno y Gabriela Gallegos, por brindarme su apoyo, protección y compartirme su experiencia durante mi aprendizaje y desenvolvimiento en el entorno laboral. Y finalmente, a todos mis amigos y amigas por todas las vivencias inolvidables que hemos pasado juntos durante estos últimos cuatro años. Ahora podemos mirar hacia atrás y darnos cuenta de cuánto hemos madurado y aprendido en esta etapa que culmina pero que no implica el fin de nuestra amistad. ÍNDICE GENERAL 1. TEMA 1 2. -

Australian Press Council Member Publications November 2018

Australian Press Council Member Publications November 2018 The following titles are published by, or are members of, the constituent body under which they are listed. They are subject to the Press Council’s jurisdiction in relation to standards of practice and adjudication of complaints. Australian Rural Publishers Association Agriculture Today ALFA Lot Feeding Australian Cotton and Grain Outlook Australian Dairyfarmer Australian Farm Journal Australian Horticulture Farm Weekly Farming Small Areas Good Fruit and Vegetables GrapeGrowers and Vignerons Horse Deals Irrigation and Water Resources North Queensland Register Northern Dairy Farmer Queensland Country Life Ripe Smart Farmer Stock and Land Stock Journal The Grower The Land Turfcraft International Bauer Media Group 4 x 4 Australia OK Magazine Aus Gourmet Traveller Magazine Owner Driver Magazine Aust Bus and Coach People Magazine Australian Geographic Picture Magazine Australian House & Garden Magazine AWW Puzzle Book Australian Transport News Real Living Magazine Australian Women's Weekly Street Machine Belle (excluding Band-ons) Take 5 Deals On Wheels Take 5 Pocket Puzzler Earth Movers & Excavators Magazine Take 5 Mega Puzzler Elle TV Week Empire Magazine Unique Cars Magazine Farms & Farm Machinery Wheels Good Health Magazine Woman's Day Harper’s Bazaar Woman’s Day Super Puzzler Money Magazine 100% Home Girls Motor NW Community Newspapers Australia Adelaide Matters Dandenong Journal Advocate Diamond Valley Leader Albert and Logan News East Torrens Messenger Auburn Review Pictorial -

Risk Assessment of Threats to Water Quality in Gulf St Vincent

ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION AUTHORITY A RISK ASSESSMENT OF THREATS TO WATER QUALITY IN GULF ST VINCENT APRIL 2009 A risk assessment of threats to water quality in Gulf St Vincent A risk assessment of threats to water quality in Gulf St Vincent Author: Sam Gaylard For further information please contact: Information Officer Environment Protection Authority GPO Box 2607 Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone: (08) 8204 2004 Facsimile: (08) 8124 4670 Free call (country): 1800 623 445 Website: <www.epa.sa.gov.au> Email: <[email protected]> ISBN 978-1-921125-90-X April 2009 This publication is a guide only and does not necessarily provide adequate information in relation to every situation. This publication seeks to explain your possible obligations in a helpful and accessible way. In doing so, however, some detail may not be captured. It is important, therefore, that you seek information from the EPA itself regarding your possible obligations and, where appropriate, that you seek your own legal advice. © Environment Protection Authority This document may be reproduced in whole or part for the purpose of study or training, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source and to it not being used for commercial purposes or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires the prior written permission of the Environment Protection Authority. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................1 GENERAL SUMMARY......................................................................................3 -

Representation Review Report

Representation Review Report Prepared in accordance with Section 12(8a) of the Local Government Act 1999 October 2016 Prepared for the City of Port Adelaide Enfield by C L Rowe and Associates Pty Ltd, September 2016 (Version 1) Disclaimer The information, opinions and estimates presented herein or otherwise in relation hereto are made by C L Rowe and Associates Pty Ltd in their best judgment, in good faith and as far as possible based on data or sources which are believed to be reliable. With the exception of the party to whom this document is specifically addressed, C L Rowe and Associates Pty Ltd, its directors, employees and agents expressly disclaim any liability and responsibility to any person whether a reader of this document or not in respect of anything and of the consequences of anything done or omitted to be done by any such person in reliance whether wholly or partially upon the whole or any part of the contents of this document. All information contained within this document is confidential. Copyright No part of this document may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the City of Port Adelaide Enfield or C L Rowe and Associates Pty Ltd. Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Background 2 3. Initial Public Consultation 3 4. Proposal 5 5. Proposal Rationale 8 5.1 Principal Member 5.2 Wards/No Wards 5.3 Area Councillors (in addition to ward Councillors) 5.4 Ward Names 5.5 Number of Councillors 6. Legislative Requirements 13 6.1 Quota 6.2 Communities of Interest and Population 6.3 Topography 6.4 Feasibility of Communication 6.5 Demographic Trends 6.6 Adequate and Fair Representation 6.7 Section 26, Local Government Act 1999 7. -

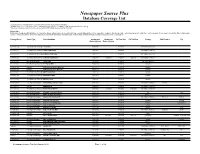

Newspaper Source Plus

Newspaper Source Plus Database Coverage List "Cover-to-Cover" coverage refers to sources where content is provided in its entirety "All Staff Articles" refers to sources where only articles written by the newspaper’s staff are provided in their entirety "Selective" coverage refers to sources where certain staff articles are selected for inclusion Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Coverage Policy Source Type Publication Name Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Start Full Text Stop Country State/Province City Abstracting Start Abstracting Stop Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News Transcript 20/20 (ABC) 01/01/2006 01/01/2006 United States of America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News Transcript 48 Hours (CBS News) 12/01/2000 12/01/2000 United States of America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News Transcript 60 Minutes (CBS News) 11/26/2000 11/26/2000 United States of America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News Transcript 60 Minutes II (CBS News) 11/28/2000 06/29/2005 11/28/2000 06/29/2005 United States of America Cover-to-Cover International Newspaper 7 Days (UAE) 11/15/2010 11/15/2010 United Arab Emirates Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News Transcript 7.30 Report (ABC) 11/28/2002 11/28/2002 Australia Cover-to-Cover Newswire AAP Australian National News Wire 09/13/2003 09/13/2003 Australia Cover-to-Cover Newswire AAP Australian Sports News Wire 10/25/2000 10/25/2000 Australia Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News Transcript ABC Premium News 01/29/2003 01/29/2003 Australia Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News Transcript ABC Regional News 01/07/2003 01/07/2003 Australia Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News Transcript ABC Rural News 12/02/2002 12/02/2002 Australia All Staff Articles U.S. -

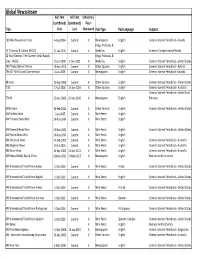

April 2019 Proquest Title List.Xlsx

Global Newsstream Full Text Full Text Scholarly / (combined) (combined) Peer‐ Title First Last Reviewed Pub Type Pub Language Subjects 100 Mile House Free Press 4‐Aug‐2004 Current N Newspapers English General Interest Periodicals‐‐Canada Blogs, Podcasts, & 13.7 Cosmos & Culture [BLOG] 21‐Jan‐2016 Current N Websites English Sciences: Comprehensive Works 24‐Hour Dorman [The Gazette, Cedar Rapids, Blogs, Podcasts, & Iowa ‐ BLOG] 21‐Jul‐2009 1‐Dec‐2011 N Websites English General Interest Periodicals‐‐United States 24X7 News Bahrain Online 19‐Dec‐2010 Current N Other Sources English General Interest Periodicals‐‐Bahrain The 40 ‐ Mile County Commentator 6‐Jan‐2009 Current N Newspapers English General Interest Periodicals‐‐Canada 48 hours 15‐Aug‐2009 Current N Other Sources English General Interest Periodicals‐‐United States 7.30 17‐Jul‐2003 11‐Apr‐2019 N Other Sources English General Interest Periodicals‐‐Australia General Interest Periodicals‐‐United Arab 7DAYS 25‐Dec‐2006 22‐Dec‐2016 N Newspapers English Emirates @This Hour 10‐Feb‐2014 Current N Other Sources English General Interest Periodicals‐‐United States AAP Bulletin Wire 1‐Jan‐2005 Current N Wire Feeds English AAP Finance News Wire 24‐Nov‐2004 Current N Wire Feeds English AAP General News Wire 24‐Nov‐2004 Current N Wire Feeds English General Interest Periodicals‐‐United States AAP Sports News Wire 24‐Nov‐2004 Current N Wire Feeds English ABC Premium News 24‐Feb‐2003 Current N Wire Feeds English General Interest Periodicals‐‐Australia ABC Regional News 10‐Jul‐2003 Current N Wire Feeds