The Right to the Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capacity Building Programme

Capacity Building Programme Volume - XI Graded List of Heritage Buildings Grade-I, Grade-IIA & Grade-IIB Premises as on 25. 2. 2009 Kolkata Municipal Corporation 5, S. N. Banerjee Road Kolkata -700 013 EPABX - 2286-1000 (22 Lines) www.kolkatamycity.com FOREWORD 1. The Government of West Bengal, by a resolution No. 5584-UD/O/M/SB/S-22/96 dated 6th October 1997, constituted a Committee known as “Expert Committee on Heritage Buildings” to identify the heritage buildings and sites in Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) area. The said Expert Committee submitted its final report to the State Government on 02.11.1998. The report was discussed in a meeting on 01.12.1998, which was presided over by the Hon’ble M.I.C., Home (Police) and I & CA Departments, and attended by, inter alia, the Hon’ble M.I.C., Urban Development Department and the Hon’ble Mayor of Kolkata; the Principal Secretary, Urban Development Department; the Secretary, Municipal Affairs Department; the Chief Executive Officer, KMDA etc. It was decided in the meeting that the list recommended by the Committee would be sent to KMC for the acceptance and for taking suitable actions towards the preservation and conservation of those heritage buildings/sites in terms of the KMC Act, 1980 (Amendment). The KMC accepted and adopted the report in principle. 2. Meanwhile, in 1997 the Chapter XXIIIA was inserted in the KMC Act 1980 for introducing a Chapter for preservation and conservation of the heritage buildings. The Chapter and the provisions therein are self-explanatory. 3. Thus, by 1998, KMC had two instrumentalities. -

Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata∗

Modern Asian Studies: page 1 of 39 C Cambridge University Press 2017 doi:10.1017/S0026749X16000913 REVIEW ARTICLE Goddess in the City: Durga pujas of contemporary Kolkata∗ MANAS RAY Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, India Email: [email protected] Tapati Guha-Thakurta, In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata (Primus Books, Delhi, 2015). The goddess can be recognized by her step. Virgil, The Aeneid,I,405. Introduction Durga puja, or the worship of goddess Durga, is the single most important festival in Bengal’s rich and diverse religious calendar. It is not just that her temples are strewn all over this part of the world. In fact, goddess Kali, with whom she shares a complementary history, is easily more popular in this regard. But as a one-off festivity, Durga puja outstrips anything that happens in Bengali life in terms of pomp, glamour, and popularity. And with huge diasporic populations spread across the world, she is now also a squarely international phenomenon, with her puja being celebrated wherever there are even a score or so of Hindu Bengali families in one place. This is one Bengali festival that has people participating across religions and languages. In that ∗ Acknowledgements: Apart from the two anonymous reviewers who made meticulous suggestions, I would like to thank the following: Sandhya Devesan Nambiar, Richa Gupta, Piya Srinivasan, Kamalika Mukherjee, Ian Hunter, John Frow, Peter Fitzpatrick, Sumanta Banjerjee, Uday Kumar, Regina Ganter, and Sharmila Ray. Thanks are also due to Friso Maecker, director, and Sharmistha Sarkar, programme officer, of the Goethe Institute/Max Mueller Bhavan, Kolkata, for arranging a conversation on the book between Tapati Guha-Thakurta and myself in September 2015. -

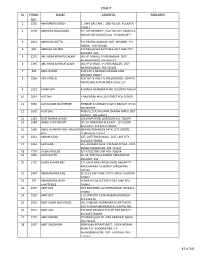

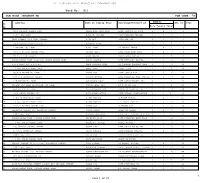

Sl Form No. Name Address Remarks

STARLIT SL FORM NAME ADDRESS REMARKS NO. 1 2235 ABHIMANYU SINGH 2, UMA DAS LANE , 2ND FLOOR , KOLKATA- 700013 2 1998 ABHISHEK MAJUMDER R.P. APPARTMENT , FLAT NO-303 PRAFULLA KANAN (W) KOLKATA-101 P.S-BAGUIATI 3 1922 ABHRANIL DUTTA P.O-PRAFULLANAGAR DIST-24PGS(N) , P.S- HABRA , PIN-743268 4 860 ABINASH HALDER 139 BELGACHIA EAST HB-6 SALT LAKE CITY KOLKATA -106 5 2271 ABU HENA MONIRUL ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI, P.S-REJINAGAR DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 6 1395 ABU HENA SAHINUR ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI , P.S-REGINAGAR , DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 7 446 ABUL HASAN B 32 1AH 3 MIAJAN OSTAGAR LANE KOLKATA 700017 8 3286 ADA AFREEN FLAT NO 9I PINES IV GREENWOOD SONATA NEWTOWN ACTION AREA II KOL 157 9 1623 ADHIR GIRI 8 DURGA CHANDRA ROAD KOLKATA 700014 10 2807 AJIT DAS 6 RAJENDRA MULLICK STREET KOL-700007 11 3650 AJIT KUMAR MUKHERJEE SHIBBARI K,S ROAD P.O &P.S NAIHATI DT 24 PGS NORTH 12 1602 AJOY DAS PO&VILL SOUTH GARIA CHARAK MATH DIST 24 PGS S PIN 743613 13 1261 AJOY KUMAR GHOSH 326 JAWPUR RD. DUMDUM KOL-700074 14 1584 AKASH CHOUDHURY DD-19, NARAYANTALA EAST , 1ST FLOOR BAGUIATI , KOLKATA-700059 15 2460 AKHIL CHANDRA ROY MNJUSRI 68 RANI RASHMONI PATH CITY CENTRE ROY DURGAPUR 713216 16 2311 AKRAM AZAD 227, DUTTABAD ROAD, SALT LAKE CITY , KOLKATA-700064 17 1441 ALIP JANA VILL-KHAMAR CHAK P.O-NILKUNTHIA , DIST- PURBA MIDNAPORE PIN-721627 18 2797 ALISHA BEGUM 5/2 B DOCTOR LANE KOL-700014 19 1956 ALOK DUTTA AC-64, PRAFULLA KANAN KRISHNAPUR KOLKATA -101 20 1719 ALOKE KUMAR DEY 271 SASHI BABU ROAD SAHID NAGAR PO KANCHAPARA PS BIZPUR 24PGSN PIN 743145 21 3447 -

BUS ROUTE-18-19 Updated Time.Xls LIST of DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS LIST of DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS

LIST OF DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS LIST OF DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS FOR THE SESSION 2018-19 FOR THE SESSION 2018-19 ESTIMATED TIMING MAY CHANGE SUBJECT ESTIMATED TIMING MAY CHANGE SUBJECT TO TO CONDITION OF THE ROAD CONDITION OF THE ROAD ROUTE NO - 1 ROUTE NO - 2 SL NO. LIST OF DROP STOPPAGES TIMINGS SL NO. LIST OF DROP STOPPAGES TIMINGS 1 DUMDUM CENTRAL JAIL 13.00 1 IDEAL RESIDENCY 13.05 2 CLIVE HOUSE, MALL ROAD 13.03 2 KANKURGACHI MORE 13.07 3 KAJI PARA 13.05 3 MANICKTALA RAIL BRIDGE 13.08 4 MOTI JEEL 13.07 4 BAGMARI BAZAR 13.10 5 PRIVATE ROAD 13.09 5 MANICKTALA P.S. 13.12 6 CHATAKAL DUMDUM ROAD 13.11 6 MANICKTALA DINENDRA STREET XING 13.14 7 HANUMAN MANDIR 13.13 7 MANICKTALA BLOOD BANK 13.15 8 DUMDUM PHARI 01:15 8 GIRISH PARK METRO STATION 13.20 9 DUMDUM STATION 01:17 9 SOVABAZAR METRO STATION 13.23 10 7 TANK, DUMDUM RD 01:20 10 B.K.PAUL AVENUE 13.25 11 AHIRITALA SITALA MANDIR 13.27 12 JORABAGAN PARK 13.28 13 MALAPARA 13.30 14 GANESH TALKIES 13.32 15 RAM MANDIR 13.34 16 MAHAJATI SADAN 13.37 17 CENTRAL AVENUE RABINDRA BHARATI 13.38 18 M.G.ROAD - C.R.AVENUE XING 13.40 19 MOHD.ALI PARK 13.42 20 MEDICAL COLLEGE 13.44 21 BOWBAZAR XING 13.46 22 INDIAN AIRLINES 13.48 23 HIND CINEMA XING 13.50 24 LEE MEMORIAL SCHOOL - LENIN SR. 13.51 ROUTE NO - 3 ROUTE NO - 04 SL NO. -

Ward No: 011 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 011 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 82/1 BIDHAN SARANI ROAD ABANINDRA NATH BOUR LATE SANTOSH KU BOUR 1 2 3 2 2 156/2 APC ROAD AJAY KR JAISWAL LAKHINARAYAN JAISWAL 1 2 3 5 3 GRAY STREET 72/1 GRAY STREET AJOY DAS JAGADISH DAS 2 3 5 6 4 28/C NALIN SARKAR ST,KOL-4 SADHANA KUNDU 3 2 5 7 5 1 MADHAB DAS LANE AJOY PATRA LT KARTIK PATRA 2 4 6 8 6 82/1/1 BIDHAN SARANI ROAD AKSHAY GIRI LATE PANCHANAN GIRI 1 2 3 9 7 77/1 BIDHAN SARANI ALOK MONDAL LAXMIKANTA MONDAL 4 2 6 11 8 MOHAN BAGAN LANE 3A/H/16/1 MOHAN BAGAN LANE AMALA NASKAR LATE EKADASHI NASKAR 1 2 3 13 9 A P C ROAD 156 A P C RD AMAR CHANDRA SAHA LT SANATAN CHANDRA SAHA 1 3 4 14 10 3 NO, MOHAN BAGAN LANE AMAR SHAW BIMAL SHAW 2 3 5 18 11 4C/H/4 MADHABDAS LANE AMIYA ROY LATE SATISH ROY 4 2 6 20 12 157/H/1 AROBINDA SARANI ANANTA MONDAL LATE NARENDRA NATH MONDAL 2 2 4 22 13 1/E MADHABDAS LANE ANGURBALA DASI LATE RABINDRANATH DAS 0 1 1 23 14 MADHAB DAS LANE 1E MADHAB DAS LANE ANGURI BALA DAS LT AJIT KR DAS 0 1 1 24 15 8/A MADHABDAS LANE ANIL CHANDRA DAS RABINDRA CHANDRA DAS 2 2 4 25 16 36/C NALIN SARKAR ST ANIL KUMAR MITRA LATE NIRMAL KUMAR MITRA 8 7 10+ 26 17 1/B/H/2 MADHABDAS LANE ANIMA MANDAL SUKUMAR MONDAL 4 2 6 27 18 3 NO, MOHAN BAGAN LANE ANIMA MONDAL LT SAMBHU MONDAL 2 2 4 28 19 82/1/1 BIDHAN SARANI ROAD ANIMA ROY SRIKANTA ROY 1 2 3 29 20 ARABINDA SARANI 110 ARABINDA SARANI ANITA PATRA PARITOSH PATRA 2 2 4 30 21 156/5 APC ROAD APARNA SADHUKHA LATE -

Kolkata Municipal Corporation )

We are Not the Best. But we are trying our Level Best NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE কলকাতা পুরসভার (Kolkata Municipal Corporation ) বাংলায় ‘লাকাল সল গভনেম’-এর থম মী সুেরনাথ ব2ানািজ হেলন ১৯২৩ ি()াে কলকাতা িমউিনিসপ2াল আইেনর .পিত/ এই সমেয়ই কাশীপুর, মািনকতলা, িচ3পুর এবং গােডনিরচ কলকাতার সে5 যু7 হল/ পরবতী কােল গােডনিরচেক কলকাতা থেক আলাদা করা হয়/ থম িনবািচত ময়র হেলন িচ9র:ন দাশ এবং সুভাষচ বসু হেলন িচফ এি=িকউিটভ অিফসার/ রাজ2 সরকার কেপােরশনেক অিধAহণ করার আেগ ১৯৪৮ ি()াের মাচ মাস অবিধ এই আইেন চলত শহর/ ১৯৫২ ি()াের ১ ম ‘কলকাতা িমউিনিসপ2াল অ2াF, ১৯৫১’ চালু হল/ ১৯৫৩ ি()াের ১ এিল টািলগ: কলকাতার সে5 যু7 হল/ ১৯৫১ ি()াের পৗর আইেন একজন িনবািচত ময়র, একজন ডপুিট ময়র এবং পাঁচ জন অIারম2ােনর পদ িনিদJ হল/ িতনিট সমKয়কারী কতৃ পM হল – কেপােরশন, )2ািOং কিমিট এবং কিমশনার/ ১৯৭২ ি()াে রাজ2 সরকার কেপােরশনেক অিধAহণ করেলন/ এর আেগ পযQ কাজ চলল ১৯৫১ ি()াের আইেন/ ১৯৮৪ ি()াের জানুয়াির মাস থেক কাযকর হল ‘ক2ালকাটা িমউিনিসপ2াল অ2াF, ১৯৮০’। ও আইন মাতােবক িতনিট কতৃ পMীয় Tর – কেপােরশন, ময়র পিরষদ এবং ময়র/ কলকাতা পুরসভার ময়র (Mayor of Kolkata Municipal Corporation ) নামনামনাম শপথ Aহেনর Name Oath date তািরখ ১ দশবVু িচ9 র:ন দাশ ১৬.০৪.১৯২৪ 1 Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das 16/04/1924 ২ দশিয় যতী মাহন সনZ[ ১৭.০৭.১৯২৫ 2 Deshapriya Jatindra Mohan Sengupta 17/07/1925 ৩ ] িবজয় কু মার বসু ০২.০৪.১৯২৮ 3 Sri Bijoy Kumar Basu 02/04/1928 ৪ দশিয় যতী মাহন সনZ[ ১০.০৪.১৯২৯ 4 Deshapriya Jatindra Mohan Sengupta 10/04/1929 ৫ নতািজ সুভাষ চ বসু ২২.০৮.১৯৩০ 5 Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose 22/08/1930 ৬ ডঃ িবধান চ রায় ১৫.০৪.১৯৩১ 6 Dr. -

32. West Bengal

Indian Economic Association Life Membership Profiles - WEST BENGAL WEST BENGAL Acharya, Dr. Rajat - WB-001 Deptt.of Economics,Jadavpur University,Kolkata-700032 (W.B.) Adhikari, Mr. Swapan Kumar - WB-002 Vill & P.O., Pusurah,Hooghly-712408 (W.B.) Agrawal, Mr. Dhanpat Ram - WB-003 AE-758, Salt Lake City,Kolkata-700 064 (W.B.) Agrawal, Ms. Sadhna - WB-004 AE-758, Salt Lake City,Sector-1, Kolkata-700 064, (W.B.) Ahmad, Dr. Fakruddin - WB-005 3, Nawab Sarajul Islam Lane, Kolkata-700016 (W.B.) Anand, Mr. Abhishek - WB-332 Director, Accede Technologies Pvt. Ltd., Second Floor, 110 Lake Town Block-A Kolkata- 700089 (W.B) Bagchi, Mr. Dhurjati Prasad - WB-006 79/1/1, N.N. Roy Street,P.O. Srirampur,Hooglhly-712201, (W.B.) Bagchi, Mr. Sayantani - WB-358 Paschim Das Para, Vidyasagar Sarani, P.O- Sonarpur, Kolkatta – 700150 (WB) Bagchi, Prof. (Dr.) Kanak Kanti - WB-007 Meghamathar Suryasen Pally, P.O. Kadamtala-734 011, Dist. Darjeeling (W.B.) Bandyopadhyay, Dr. D. Kumar - WB-008 A-2/8 Baitalik CooperativeHousing Society, Baga-Jatin, KMDA Complex (E.M. Bypass), Kolkata-700094 (W.B.) Bandyopadhyay, Ruby - WB-009 242/3B APC Road,Nandan Apartment, Maharaja Srischandra College, Kolkata-700004 (W.B.) IEA - Life Members - WEST BENGAL 1 Indian Economic Association Life Membership Profiles - WEST BENGAL Bandyopadhyay Dr. Subir - WB-010 3/6, Netajinagar,Post Office :-Regent Park,Kolkata-700040, (W.B.) Banerjee Mr. Basudeb - WB-012 RA-63, Sector 2B, S. S. Banerjee Sarani, Bidhan Nagar,Durgapur-713212 (W.B.) Banerjee, Dr. Dibyendu - WB-333 Assistant Professir in Economics, Amulya Kanan Housing Complex, (Phase 2), Flat No. -

Transforming Kolkata: a Partnership for a More Sustainable, Inclusive, and Resilient City

TRANSFORMING KOLKATA A PARTNERSHIP FOR A MORE SUSTAINABLE, INCLUSIVE, AND RESILIENT CITY Neeta Pokhrel MAY 2019 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK TRANSFORMING KOLKATA A PARTNERSHIP FOR A MORE SUSTAINABLE, INCLUSIVE, AND RESILIENT CITY Neeta Pokhrel MAY 2019 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2019 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2019. ISBN 978-92-9261-400-3 (print), 978-92-9261-401-0 (electronic) Publication Stock No. TCS189628-2 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS189628-2 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. -

Preface to the First Edition

Preface to the First Edition The” Treasury Rules, Bengal and the Subsidiary Rules made thereunder” were framed under section 135(1) of the Government of India Act, 1935, and brought into force as from lst April 1937. With the commencement of the Constitution of India, the rules framed under the Government of India Act, 1935, were continued in force, in so far as they were not inconsistent with the provisions of the Constitution, in the Finance Department notification-No. 3468F.B., dated the 31st March 1950, published in the Extraordinary Issue of the calcutta Gazette, dated 31st March 1950. 2. The rules referred to above, with necessary adaptation and corrections issued up to May 1952 were incorporated in the compilation of the “Treasury Rules, West Bengal and the Subsidiary Rules made thereunder” which was issued in the year 1952 under sub-clause (2) of Article 283 of the constitution of India. The present compilation supersedes the issue of the year 1952. All amendments issued up to 30th November 1965 have been incorporated in it. 3. This compilation, like the cone which it supersedes, comprises two volumes the first contains the text and the second contains the appendices and the forms. The first volume is divided into three parts- , Ø Part I contains Treasury Rules made by the Governor in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by subclause (2) of Article 283 of the Constitution of India. Ø Part II contains Subsidiary Rules which were framed by the Finance Minister in consultation with the Accountant –General of the Reserve Bank of India, as the case may be, m exercise of the power delegated to him under certain Treasury Rules. -

16‐06‐20 13 5 Seals Garden Lane Cossipore 700002 1 1

Affected Zone DAYS SINCE Date of reporting of REPORTING Sl No. Address Ward Borough Local area the case 13 5 SEALS GARDEN LANE The premises itself 1 1 1 Cossipore 16‐06‐20 COSSIPORE 700002 14 The affected flat/the 59 Kalicharan Ghosh Rd standalone house 2 kolkata ‐ 700050 West 2 1 Sinthi Bengal India 16‐06‐20 14 The premises itself 21/123 RAJA MANINDRA 3 31 Paikpara ROAD BELGACHIA 700037 16‐06‐20 14 14A BIRPARA LANE The premises itself 4 kolkata ‐ 700030 West 31 Belgachia 16‐06 ‐20 BBlIdiengal India 14 The flat itself A4 6 R D B RD Kolkata ‐ 5 41 Paikpara 700002 West Bengal India 16‐06‐20 14 110/1A COSSIPORE Road The premises itself 6 Kolkata ‐ 700002 West 6 1 Chitpur 16‐06‐20 Bengal India 14 Adjacent common passage of affected hut 14 3 GALIFF STREET 7 7 1 Bagbazar including toilet and BAGHBAZAR 700003 water source of the 16‐06‐20 slum 14 Adjacent common passage of affected hut 14 3 GALIFF STREET 8 7 1 Bagbazar including toilet and BAGHBAZAR 700003 water source of the 16‐06‐20 slum 14 Affected Zone DAYS SINCE Date of reporting of REPORTING Sl No. Address Ward Borough Local area the case 1 RAMKRISHNA LANE The premises itself 9 Kolkata ‐ 700003 West 7 1 Girish Mancha 16‐06‐20 Bengal India 14 The premises itself 4/2/1B KRISHNA RAM BOSE 10 STREET SHYAMPUKUR 10 2 Shyampukur KOLKATA 700004 16‐06‐20 14 T/1D Guru Charan Lane The premises itself 11 Kolkata ‐ 700004 West 10 2 Hatibagan 16‐06‐20 Bengal India 14 Adjacent common 47 1 SHYAMBAZAR STREET passage of affected hut 12 Kolk at a ‐ 700004 W est 10 2 Shyampu kur iilditiltdncluding toilet and -

Kolkata Train

Here is the complete history of Kolkata tram routes, from 1873 to 2020. HORSE TRAM ERA 1873 – Opening of horse tram as meter gauge, closure in the same year. 1880 – Final opening of horse tram as a permanent system. Calcutta Tramways Company was established. 1881 – Dalhousie Square – Lalbazar - Bowbazar – Lebutala - Sealdah Station. (Later route 14) Esplanade – Lalbazar – Pagyapatti – Companybagan - Shobhabazar - Kumortuli. (Later route 7 after extension) Dalhousie Square – Esplanade. (Later route 22, 24, 25 & 29) Esplanade – Planetarium - Hazra Park - Kalighat. (Later route 30) 1882 - Esplanade – Wellington Square – Bowbazar – Boipara - Hatibagan - Shyambazar Junction. (Later route 5) Wellington Square – Moula Ali - Sealdah Station. (Later route 12 after extension) Dalhousie Square – Metcalfe Hall - High Court. (Later route 14 extension) Metcalfe Hall – Howrah Bridge - Nimtala. (Later route 19). Steam tram service was thought. STEAM TRAM ERA 1883 - Esplanade – Racecourse - Wattganj - Khidirpur. (Later route 36) 1884 - Wellington Square – Park Street. (Later route 21 & 22 after extension) 1900 - Nimtala – Companybagan (non-revenue service only). Electrification & conversion to standard gauge was started. ELECTRIC TRAM ERA 1902 - Khidirpur & Kalighat routes were electrified. Shobhabazar – Hatibagan. (Later route 9 & 10) Nonapukur Workshop opened with Royd Street – Nonapukur (Later route 21 & 22 after re-extension). Royd Street – Park Street closed. 1903 – Shyambazar terminus opened with Shyambazar – Belgachhia. (Later route 1, 2, 3, 4 & 11) Kalighat – Tollyganj. (Later route 29 & 32) 1904 - Kumortuli – Bagbazar. Kumortuli terminus closed. (Later route 7 & 8) 1905 - Howrah Bridge – Pagyapatti – Boipara – Purabi Cinema - Sealdah Station (Later route 15). All remaining then-opened routes were electrified. 1907 - Moula Ali – Nonapukur. (Later route 20 & 26 after extension) Wattganj – Mominpur (via direct access through Ofphanganjbazar). -

Containment Zones in West Bengal

We have two Containment Zones as on 04.05.20 for Darjeeling District: 1. Ward No 47, Siliguri Municipal Corporation. 2.Shantiniketan Housing Complex, Shusrat Nagar, Matigara Block. Containment Zones in Hooghly District ZONE CODE ZONE DETAILS 1 Sarai-tinna GP Purushortampur Pandua, PANDUA,SADAR 2 W-12 Champdani Muni-Chandannagar, CHAMPDANI MUNICIPALITY,CHANDANNAGAR 3 W-12 Konnagar Muni-Srerampore-U, KONNAGAR MUNICIPALITY,SRIRAMPORE 4 W-19 Serampore M-Srerampore-U, SERAMPORE MUNICIPALITY,SRIRAMPORE 5 W-11 Dankuni M-Srerampore-U, DANKUNI MUNICIPALITY,SRIRAMPORE 6 Rishra GP Sansad No-1 Malik Para, Mollaber SU Block Serampore-R, SRIRAMPORE-UTTARPARA,SRIRAMPORE 7 W-17 Srerampore M-Srerampore-U, SERAMPORE MUNICIPALITY,SRIRAMPORE 8 W-8 CMC Chandannagar, CHANDANNAGAR MUNICIPALITY,CHANDANNAGAR 9 W-18 srerampore M-Srerampre-U, SERAMPORE MUNICIPALITY,SRIRAMPORE 10 Sugandhaya GP Sansad 15 Gotu-Madhya-Sadar, POLBA-DADPUR,SADAR 11 Kanaipur GP-SU Block Srerampore, SRIRAMPORE-UTTARPARA,SRIRAMPORE 12 Barjhati GP Chanditala II Bl Srerampore, CHANDITALA-II,SRIRAMPORE 13 W- 1 Rishra M, Masjid Para, Srerampore, RISHRA MUNICIPALITY,SRIRAMPORE 14 W-2, Gokhanan, RISHRA MUNICIPALITY,SRIRAMPORE 15 Tirole GP, Arambagh, ARAMBAGH,ARAMBAG 16 W 11- CMC -Urdi Bazar, CHANDANNAGAR MUNICIPALITY,CHANDANNAGAR 17 W 12- CMC -Urdi Bazar , CHANDANNAGAR MUNICIPALITY,CHANDANNAGAR 18 W -29 Srerampore M Prabhasnagar, SERAMPORE MUNICIPALITY,SRIRAMPORE We have the following Containment Zones as on 04.05.20 for Jalpaiguri District: 1.Ward No 40, 41,.42 and 43 under Siliguri Municipal