Current Status and Distribution of Birds of Prey in the Canary Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Documento Archipiélago Chinijo

Archipiélago Chinijo Situación, amenazas y medidas de conservación Archipiélago Chinijo Situación, amenazas y medidas de conservación © WWF España Gran Vía de San Francisco, 8-D 28005 Madrid Tel.: 91 354 05 78 Fax: 91 365 63 36 [email protected] www.wwf.es © Canarias por una Costa Viva Mediateca Guiniguada Camino de Salvago, s/n (frente Urb. Zurbarán) Campus Universitario de Rafira 35017 Las Palmas de Gran Canaria Tel. 928 45 74 55/56 Fax. 928 45 74 57 [email protected] www.canariasporunacostaviva.org Texto: Juan Alexis Rivera Coordinación: José A. Trujillo y José Luis García Varas Fotos portada: WWF/Juan Alexis Rivera Edición: Jorge Bartolomé Diseño: Amalia Maroto 1ª edición Mayo 2004 Última actualización Junio 2010 “Canarias, por una costa viva” es un proyecto que integra programas de investigación, sensibilización, educación y conservación del litoral canario promovido por La Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria y WWF España y financiado por La Dirección General de Costas del Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Medio Rural y Marino Índice Introducción 1. Valores naturales 1.1. Geología 1.2. Biodiversidad taxonómica terrestre 1.3. Biodiversidad taxonómica marina 2. Sistema socioeconómico 2.1. Población 2.2. Actividades económicas, usos y aprovechamientos de los recursos 2.3. Régimen administrativo y propiedad del espacio 2.4. Valores culturales 3. Figuras de protección 3.1. Antecedentes 3.2. Parque Natural del Archipiélago Chinijo 3.3. Reserva Natural Integral de los Islotes 3.4. Reserva Marina 3.5. Zonas Especiales de Protección para las Aves (ZEPAs) 3.6. Zonas Especiales de Conservación (ZEC) 3.7. Reserva de Biosfera de la Isla de Lanzarote 4. -

( 7)-Revista Ac. Nº 84

Ardeol a 67(2), 2020, 449 -494 DOI: 10.13157/arla.67.2.2020.on NOTICIARIO ORNITOLÓGICO ORNITHOLOGICAL NEWS 1 2 3 Blas MOLIN A , Javier PRIET A , Juan Antonio LORENZ O (Canarias) 4 y Carlos LÓPEZ -JURAD O (Baleares) RESUMEN .— En este informe se muestra información sobre 149 especies que se reparten por toda la geografía nacional. Entre ellas, se incluyen 28 especies que aparecen de forma escasa para las que se muestra su distribución espacio-temporal en 2019 mediante mapas y gráficas (véase De Juana y Garcia, 2015; Gil-Velasco et al ., 2018; Rouco et al ., 2018). Para contabilizar el número de citas para cada espe- cie escasa se revisaron las observaciones disponibles en diferentes plataformas de recogida de datos, especialmente en eBird ( eBird , 2020; Observado , 2020; Reservoir Birds , 2020 y Ornitho , 2020), des - cartando aquellas que aparentemente correspondieran a las mismas citas hechas por diferentes observa - dores con el objeto de contar con muestras de datos lo suficientemente homogéneas. Para el archipiélago canario, se incorpora un buen número de citas correspondientes al episodio de calima que se produjo a finales de febrero de 2020. Dichas circunstancias meteorológicas provocaron la arribada de muchas aves accidentales procedentes del noroeste africano de las que dará cuenta el correspondiente informe del Comité de Rarezas de SEO/BirdLife, junto con muchas otras especies de paso que se pudieron observar en las islas con mayor frecuencia y en números más altos de lo habitual, y de las que se sinte- tiza en el presente informe aquellas observaciones más relevantes. Se sigue la secuencia taxonómica de acuerdo con la nueva lista patrón de las aves de España (Rouco et al ., 2019). -

CANARY ISLANDS at the SPANISH PAVILION 30Th MAY to 5Nd JUNE

CANARY ISLANDS AT THE SPANISH PAVILION 30th MAY to 5nd JUNE 2005 From the 30th of May until the 5th of June, the Spanish Pavilion will celebrate the CANARY ISLANDS region week. On the 4th of June, the Canary Islands will be celebrating its official day. For this special occasion the Spanish Pavilion is honoured to receive the Official Delegation from this region headed by their President Adan Martín. Spain is divided into seventeen autonomous regions, each of them with its own government. During EXPO Aichi 2005 the Spanish Pavilion will have the participation of its regional governments and autonomous cities to show Spain’s natural diversity and cultural pluralism. Each Spanish autonomic region will have the use of the Pavilion for an entire week in order to display its cultural roots as well as the most outstanding features of its land and peoples, through dance, musicians, theater, exhibitions, and an audiovisual projection in the Plaza. Spain’s regions will use this opportunity to show typical products and objects of their cuisine, customs, and craft traditions. The flag of each region will fly alongside the Spanish, Japanese and European flags over the main gate for a week. During its featured week, each region will have a special day. The Canary Islands, a paradisiac group of islands with a preferred climate and constant temperature through out the year, and splendid beaches of fine sand, consists of 7 large islands (Gran Canaria, Fuerteventura, Lanzarote, Tenerife, La Palma, Gomera, Hierro) and a few smaller ones (Alegranza, Graciosa, Montaña Clara, Roque del Este, Roque del Oeste and Lobos). -

Seabirds in the Northern Islets of Lanzarote, Canary Islands

2003 Breeding seabirds in Lanzarote 41 Status and distribution of breeding seabirds in the northern islets of Lanzarote, Canary Islands Beneharo Rodríguez Leandro de León Aurelio Martín Jesús Alonso & ManuelNogales Rodriguez B., de León L., Martin A., Alonso J. & Nogales M. 2003. Status and distribution of breeding seabirds in the northern islets of Lanzarote, Canary Islands. Atlantic We describe the results Seabirds 5(2): 41-56. ofa survey ofbreeding seabirds carried out between 2000 and 2002 in the northern islets of Lanzarote, Canary Islands, with particular emphasis on their status and distribution. For White-faced Storm- petrel Pelagodroma marina, Madeiran Storm-petrel Oceanodroma Castro, Lesser Black- backed Gull Larus [fuscus] graellsii and Yellow-leggedGull Larus cachinnans atlantis, some new colonies were discovered on different islets. All species have maintained their numbers the last 15 with the the which over years, exception of Yellow-leggedGull, has undergonea in well-documented increase; 1987, about 400 breedingpairs were estimated but during the present study, almost 1000 pairs were counted. In addition, some comments on threats to these seabird populations are presented. On La Graciosa, feral cats are a majorpredator of the European Storm-petrelpopulation, killing more than 50 birds duringthis study alone. Departamento de Biologia Animal (Zoologia), Universidad de La Laguna, 38206 Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The most important sites for seabirds in the Canarian archipelago are small uninhabitedrocks where introduced or islets, generally no predators are present, such as Roques de Salmor (El Hierro), Roques de Anaga (Tenerife), Isla de Lobos (Fuerteventura) and especially the northem islets of Lanzarote (known as the Chinijo Archipelago; Martin & Hemandez 1985; Martin & Nogales 1993; Martin & Lorenzo 2001). -

European Red List of Birds

European Red List of Birds Compiled by BirdLife International Published by the European Commission. opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Commission or BirdLife International concerning the legal status of any country, Citation: Publications of the European Communities. Design and layout by: Imre Sebestyén jr. / UNITgraphics.com Printed by: Pannónia Nyomda Picture credits on cover page: Fratercula arctica to continue into the future. © Ondrej Pelánek All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder (see individual captions for details). Photographs should not be reproduced or used in other contexts without written permission from the copyright holder. Available from: to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed Published by the European Commission. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. ISBN: 978-92-79-47450-7 DOI: 10.2779/975810 © European Union, 2015 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Printed in Hungary. European Red List of Birds Consortium iii Table of contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................................1 Executive summary ...................................................................................................................................................5 1. -

![Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, Coraciiformes, and Passeriformes.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0282/ciconiiformes-charadriiformes-coraciiformes-and-passeriformes-1100282.webp)

Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, Coraciiformes, and Passeriformes.]

Die Vogelwarte 39, 1997: 131-140 Clues to the Migratory Routes of the Eastern Fly way of the Western Palearctics - Ringing Recoveries at Eilat, Israel [I - Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, Coraciiformes, and Passeriformes.] By Reuven Yosef Abstract: R euven , Y. (1997): Clues to the Migratory Routes of the Eastern Fly way of the Western Palearctics - Ringing Recoveries at Eilat, Israel [I - Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, Coraciiformes, and Passeriformes.] Vogelwarte 39: 131-140. Eilat, located in front of (in autumn) or behind (in spring) the Sinai and Sahara desert crossings, is central to the biannual migration of Eurasian birds. A total of 113 birds of 21 species ringed in Europe were recovered either at Eilat (44 birds of 12 species) or were ringed in Eilat and recovered outside Israel (69 birds of 16 spe cies). The most common species recovered are Lesser Whitethroat {Sylvia curruca), White Stork (Ciconia cico- nia), Chiffchaff (Phylloscopus collybita), Swallow {Hirundo rustica) Blackcap (S. atricapilla), Pied Wagtail {Motacilla alba) and Sand Martin {Riparia riparia). The importance of Eilat as a central point on the migratory route is substantiated by the fact that although the number of ringing stations in eastern Europe and Africa are limited, and non-existent in Asia, several tens of birds have been recovered in the past four decades. This also stresses the importance of taking a continental perspective to future conservation efforts. Key words: ringing, recoveries, Eilat, Eurasia, Africa. Address: International Bird Center, P. O. Box 774, Eilat 88106, Israel. 1. Introduction Israel is the only land brigde between three continents and a junction for birds migrating south be tween Europe and Asia to Africa in autumn and north to their breeding grounds in spring (Yom-Tov 1988). -

Lanzarote | Fuerteventura | Gran Canaria | Tenerife | La Gomera | La Palma | El Hierro2 Canary Islands, the Smart Filming

LANZAROTE | FUERTEVENTURA | GRAN CANARIA | TENERIFE | LA GOMERA | LA PALMA | EL HIERRO2 CANARY ISLANDS, THE SMART FILMING Their mild climate year-round and unique In addition, the Canary Islands offer a wide range landscapes attract millions of tourists to the of incredibly beautiful and diverse locations Canary Islands every year. But the islands have within a few kilometres from one another. The also seen how a rising number of both Spanish Archipelago meets all the requirements as a and foreign production companies have chosen natural set thanks to its mild climate and its these Spanish archipelago as the location to more than 3,000 hours of sunlight per year. As a shoot their films. leading tourist destination, the islands have top hotel infrastructure and excellent air and sea Why is there so much interest in shooting in the connections, besides something that is currently Canaries? Undoubtedly, their extraordinary tax most appreciated: safety. incentives (40% tax rebate for foreign productions and up to 45% for national productions). As an Shooting in the Canary Islands is easy: seasoned outermost region of the European Union, the professionals with experience in all kind of Canaries have a specific economic and fiscal productions plus the local film commissions, regime, which means deductions for investment which are always ready to help. And to cap it all, if benefit from 20 extra points; 80% higher than in you decide to set up your business here, you’ll pay the rest of Spain. a reduced corporate income tax rate of only 4%. Why not join the Smart Filming? 2 WHY FILM IN THE CANARY ISLANDS? 1 TAX INCENTIVES * TAX REBATE FOR FOREIGN CORPORATE INCOME TAX RATE IGIC 40% PRODUCTIONS 4% ZEC Canary Islands Special Zone 0% (REGIONAL VAT) Basic requirements: The audiovisual companies based on the A zero rate is applied to the production - A million euros spent in the Canary Islands islands can benefit from a reduced Corporate of feature films, drama, animation or - Minimum production budget 2 million euros Income Tax rate of 4% as ZEC entities documentary series. -

Molina-Et-Al.-Canary-Island-FH-FEM

Forest Ecology and Management 382 (2016) 184–192 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Fire history and management of Pinuscanariensis forests on the western Canary Islands Archipelago, Spain ⇑ Domingo M. Molina-Terrén a, , Danny L. Fry b, Federico F. Grillo c, Adrián Cardil a, Scott L. Stephens b a Department of Crops and Forest Sciences, University of Lleida, Av. Rovira Roure 191, 25198 Lleida, Spain b Division of Ecosystem Science, Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, 130 Mulford Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3114, USA c Department of the Environment, Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Av. Rovira Roure 191, 25198 Gran Canaria, Spain article info abstract Article history: Many studies report the history of fire in pine dominated forests but almost none have occurred on Received 24 May 2016 islands. The endemic Canary Islands pine (Pinuscanariensis C.Sm.), the main forest species of the island Received in revised form 27 September chain, possesses several fire resistant traits, but its historical fire patterns have not been studied. To 2016 understand the historical fire regimes we examined partial cross sections collected from fire-scarred Accepted 2 October 2016 Pinuscanariensis stands on three western islands. Using dendrochronological methods, the fire return interval (ca. 1850–2007) and fire seasonality were summarized. Fire-climate relationships, comparing years with high fire occurrence with tree-ring reconstructed indices of regional climate were also Keywords: explored. Fire was once very frequent early in the tree-ring record, ranging from 2.5 to 4 years between Fire management Fire suppression fires, and because of the low incidence of lightning, this pattern was associated with human land use. -

Canary Islands

CANARY ISLANDS EXP CAT PORT CODE TOUR DESCRIPTIVE Duration Discover Agadir from the Kasbah, an ancient fortress that defended this fantastic city, devastated on two occasions by two earthquakes Today, modern architecture dominates this port city. The vibrant centre is filled with Learn Culture AGADIR AGADIR01 FASCINATING AGADIR restaurants, shops and cafes that will entice you to spend a beautiful day in 4h this eclectic city. Check out sights including the central post office, the new council and the court of justice. During the tour make sure to check out the 'Fantasy' show, a highlight of the Berber lifestyle. This tour takes us to the city of Taroudant, a town noted for the pink-red hue of its earthen walls and embankments. We'll head over by coach from Agadir, seeing the lush citrus groves Sous Valley and discovering the different souks Discover Culture AGADIR AGADIR02 SENSATIONS OF TAROUDANT scattered about the city. Once you have reached the centre of Taroudant, do 5h not miss the Place Alaouine ex Assarag, a perfect place to learn more about the culture of the city and enjoy a splendid afternoon picking up lifelong mementos in their stores. Discover the city of Marrakech through its most emblematic corners, such as the Mosque of Kutubia, where we will make a short stop for photos. Our next stop is the Bahia Palace, in the Andalusian style, which was the residence of the chief vizier of the sultan Moulay El Hassan Ba Ahmed. There we will observe some of his masterpieces representing the Moroccan art. With our Feel Culture AGADIR AGADIR03 WONDERS OF MARRAKECH guides we will have an occasion to know the argan oil - an internationally 11h known and indigenous product of Morocco. -

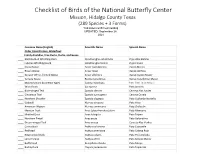

Bird Checklist

Checklist of Birds of the National Butterfly Center Mission, Hidalgo County Texas (289 Species + 3 Forms) *indicates confirmed nesting UPDATED: September 28, 2021 Common Name (English) Scientific Name Spanish Name Order Anseriformes, Waterfowl Family Anatidae, Tree Ducks, Ducks, and Geese Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Pijije Alas Blancas Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Pijije Canelo Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Ganso Blanco Ross's Goose Anser rossii Ganso de Ross Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons Ganso Careto Mayor Canada Goose Branta canadensis Ganso Canadiense Mayor Muscovy Duck (Domestic type) Cairina moschata Pato Real (doméstico) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Pato Arcoíris Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Cerceta Alas Azules Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cerceta Canela Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Pato Cucharón Norteño Gadwall Mareca strepera Pato Friso American Wigeon Mareca americana Pato Chalcuán Mexican Duck Anas (platyrhynchos) diazi Pato Mexicano Mottled Duck Anas fulvigula Pato Tejano Northern Pintail Anas acuta Pato Golondrino Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Cerceta Alas Verdes Canvasback Aythya valisineria Pato Coacoxtle Redhead Aythya americana Pato Cabeza Roja Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Pato Pico Anillado Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Pato Boludo Menor Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Pato Monja Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis Pato Tepalcate Order Galliformes, Upland Game Birds Family Cracidae, Guans and Chachalacas Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula Chachalaca Norteña Family Odontophoridae, -

La Vegetación De La Graciosa Como Sigue

MONOGRAPHIAZ BlOLOGIC/E CAiVARlEiVSl-S N.0 2 La Vegelaciún de La Graciosa y notas sobre Alegranza, Montaña Clara y el Roque de2 Inji.erno (Con 2 mapas y 10 fotografías) por G. Kunkel Excmo. Cabildo Insular de Gran Canaria Las Palmas, Diciembre de 1971 Monogr. Biol. Canar. 2; 1971 I Dirección de la Redaccidn: Finca “Llano de la Piedra” Santa Lucía de Tirajana Gran Canaria, ‘España Depósito Legal: GC - 79-1970 Edición 400 ejempIares Precio de este número: Ptas. 120,- Imp. Pfkez Galdós, calle Buenos Aires, 38 Las Palmas de Gran Canaria - 4- Indice Agradecimientos ................. 6 Introducción ................... 7 El caracter geográfico y geológico de las Isletas ..... 9 La vegetación de las Isletas ............. 15 La Graciosa .................. 18 Notas sobre la vegetación de Montaña Clara ...... 45 Roque del Infierno o del Oeste ........... 49 La vegetación de la Isla de Alegranza ........ 49 Discusiones y comparaciones ............. 56 Rcsumcn .................... 59 Sumario ................... 60 Literatura citada ................. 61 Apéndices .................... 63 Sobre el futuro probable de las Islas Menores ..... 63 Musgos de La Graciosa .............. 65 Registro (Enumeración de La Graciosa) ......... 66 -5- Agradecimientos El autor quiere agradecer a todas las instituciones y per- sonas particulares que han ayudado en cuanto a los viajes y la identificación de plantas colectadas. Se agradece al EXcino. Cabildo Insular de Gran Canaria (Las Palmas), la beca donada y los mapas militares del área estudiada: al Iltmo. Sr. Delegado Provincial del Ministerio de Informa- ción y Turismo (Las Palmas), su carta de introducción y su interés en el trabajo; RI Tltmo. Ayuntamiento de Arrecife (Lanzarote), SII inestima- ble cooperación y al Museo Canario, de Las Palmas, la literatura facilitada. -

Introducción Y Memoria Informativa

Plan Rector de Uso y Gestión Plan Especial Prot. Paisajística Normas de Conservación Plan Especial de Protección Paisajística Color reserva natural especial [en pantone machine system PANTONE 347 CV] Plan Director Color para parques naturales [ PANTONE 116 CV ] Color gris de fondo [Modelo RGB: R - 229,G - 229, B - 229] N IÓ AC RM CA O LI NF B I PÚ Plan Rector de Uso y Gestión OO AAJJ AABB TTRR NN Parque Natural IIÓÓ del CC Archipiélago Chinijo AA CCEE BB AANN OO AAVV PPRR AA Parque Rural Parque Natural AA Reserva Natural Integral IIVV Reserva Natural Especial IITT Sendero IINN Paisaje Protegido FF Monumento Natural DDEE Sitio de Interés Científico Introducción y Memoria Informativa La Comisión de Ordenación del Territorio y Medio Ambiente de Canarias, en sesión de fecha: 10-JULIO-2006 acordó la APROBACIÓN DEFINITIVA del presente expediente: Las Palmas de G.C. 11-AGOSTO-2006 1 6 200 L ORIA RIO IT tiva i O R N fin e Ó RRIT ión D ÓN TER I Uso y Gestión C robac NA AS ctor de ÓN DEL TE I e ARI C N mento Ap NA Plan R Docu TE Y ORDE 2006 DEL O DE CA ORDE E ÉLAGO CHINIJO D RN L AMBIEN A GOBIE DEL PARQUE NATURAL GENER ARCHIPI N DE MEDIO IÓ A C PLAN RECTOR DE USO Y GESTI GO CHINIJO DIREC NSEJERÍ CO Parque Natural del ARCHIPIÉLA DOCUMENTO INFORMATIVO Parque Natural del Plan Rector de Uso y Gestión 2006 ARCHIPIÉLAGO CHINIJO Documento Aprobación Definitiva L e ac de L a a x Co s C o p r e P a dó d mi a narias, i l e m l s n a i a t ó e s A n : P d d R e e e O n G Or B s .