1 Carrots Or Maltesers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020

k Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020 For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk CONTENTS 5 USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS 5 EXPLANATION OF KASHRUT SYMBOLS 5 PROBLEMATIC E NUMBERS 6 BISCUITS 6 BREAD 7 CHOCOLATE & SWEET SPREADS 7 CONFECTIONERY 18 CRACKERS, RICE & CORN CAKES 18 CRISPS & SNACKS 20 DESSERTS 21 ENERGY & PROTEIN SNACKS 22 ENERGY DRINKS 23 FRUIT SNACKS 24 HOT CHOCOLATE & MALTED DRINKS 24 ICE CREAM CONES & WAFERS 25 ICE CREAMS, LOLLIES & SORBET 29 MILK SHAKES & MIXES 30 NUTS & SEEDS 31 PEANUT BUTTER & MARMITE 31 POPCORN 31 SNACK BARS 34 SOFT DRINKS 42 SUGAR FREE CONFECTIONERY 43 SYRUPS & TOPPINGS 43 YOGHURT DRINKS 44 YOGHURTS & DAIRY DESSERTS The information in this guide is only applicable to products made for the UK market. All details are correct at the time of going to press but are subject to change. For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk. Sign up for email alerts and updates on www.kosher.org.uk or join Facebook KLBD Kosher Direct. No assumptions should be made about the kosher status of products not listed, even if others in the range are approved or certified. It is preferable, whenever possible, to buy products made under Rabbinical supervision. WARNING: The designation ‘Parev’ does not guarantee that a product is suitable for those with dairy or lactose intolerance. WARNING: The ‘Nut Free’ symbol is displayed next to a product based on information from manufacturers. The KLBD takes no responsibility for this designation. You are advised to check the allergen information on each product. k GUESS WHAT'S IN YOUR FOOD k USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS Hi Noshers! PRODUCTS WHICH ARE KLBD CERTIFIED Even in these difficult times, and perhaps now more than ever, Like many kashrut authorities around the world, the KLBD uses the American we need our Nosh! kosher logo system. -

The Effects of Varying Levels of Object Change on Explicit And

THE EFFECTS OF VARYING LEVELS OF OBJECT CHANGE ON EXPLICIT AND IMPLICIT MEMORY FOR BRAND MESSAGES WITHIN ADVERGAMES A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By NICHOLAS D’ANDRADE Dr. Paul Bolls, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2007 © Copyright by Nicholas D’Andrade 2007 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE EFFECTS OF VARYING LEVELS OF OBJECT CHANGE ON EXPLICIT AND IMPLICIT MEMORY FOR BRAND MESSAGES WITHIN ADVERGAMES Presented by Nicholas D’Andrade, A candidate for the degree of Master of Arts And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance Jennifer Aubrey Professor Jennifer Aubrey Paul Bolls Professor Paul Bolls Glenn Leshner Professor Glenn Leshner Kevin Wise Professor Kevin Wise DEDICATION To Kim, whose support, friendship, patience and love help me through every single day. Thank You. To Taya, you weren’t here when I started this but you were the biggest reason that I wanted to finish. To Mom and Dad, for everything the two of you have given me, during my academic journey and otherwise. A little more of that painting is revealed... To Barb and Jim, for all your help, all your love, and for giving me a place to come home to. To TJ, for being the friend 2000 miles away who was LITERALLY always available for a late chat on the phone. To Paul and Val, who have provided unwavering support and hospitality to Kim, Taya and me. -

Know Your Emeritus Member... STAN KOPECKY

Know your Emeritus Member... STAN KOPECKY Stan founded his consulting practice, which specializes in the design, development, testing and commercialization of consumer products packaging following a distinguished career with several of the largest and most sophisticated consumer products companies in the world. He began his career as a Food Research Scientist with Armour and Company. Shortly thereafter he joined Northfield, IL-based Kraft Inc. where he progressed rapidly through positions as a Packaging Research Scientist, Assistant Packaging Manager and Packaging Manager. While at Kraft, he implemented a series of programs that generated $3-5 million per year in savings in the production of rigid and flexible packaging categories; spearheaded the development of the Company’s first Vendor Certification Program for packaging materials and developed and delivered a packaging awareness program that proved successful in improving product quality and safety. Most recently Stan served as a Senior Packaging Project Manager with Chicago, IL-based Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company, the world’s largest manufacturer and marketer of chewing gum and a leader in the confectionary field. While at Wrigley, he played a major role in the evolution of the company, going from a provider of relatively indistinguishable commodities to a consumer focused, product feature driven business. In that regard, he was instrumental in achieving the number one position in the sugarless gum category by designing the packaging for Orbit tab gum, which proved to be a powerful product differentiator and which was awarded both a U.S. patent and the Company’s Creativity Award. He supported the Company’s successful entry into the breath mint segment by designing the tin and carton packaging utilized for the introduction of the Eclipse and Excel products into the U.S. -

Unit 5 Space Exploration

TOPIC 8 People in Space There are many reasons why all types of technology are developed. In Unit 5, you’ve seen that some technology is developed out of curiosity. Galileo built his telescope because he was curious about the stars and planets. You’ve also learned that some technologies are built to help countries fight an enemy in war. The German V-2 rocket is one example of this. You may have learned in social stud- ies class about the cold war between the United States and the for- mer Soviet Union. There was no fighting with guns or bombs. However, these countries deeply mistrusted each other and became very competitive. They tried to outdo and intimidate each other. This competition thrust these countries into a space race, which was a race to be the first to put satellites and humans into space. Figure 5.57 Space shuttle Atlantis Topic 8 looks at how the desire to go into space drove people to blasts off in 1997 on its way to dock produce technologies that could make space travel a reality. with the Soviet space station Mir. Breaking Free of Earth’s Gravity Although space is only a hundred or so kilometres “up there,” it takes a huge amount of energy to go up and stay up there. The problem is gravity. Imagine throwing a ball as high as you can. Now imagine how hard it would be to throw the ball twice as high or to throw a ball twice as heavy. Gravity always pulls the ball back to Earth. -

Greenhouse Tomatoes Change the Dynamics of the North American Fresh Tomato Industry / ERR-2 Economic Research Service/USDA Contents

Electronic Report from the Economic Research Service United States Department www.ers.usda.gov of Agriculture Economic Research Report Greenhouse Tomatoes Number 2 Change the Dynamics of April 2005 the North American Fresh Tomato Industry Roberta Cook and Linda Calvin Abstract The rapid growth of the North American greenhouse tomato industry has changed the longstanding dynamics of the fresh tomato industry. During the 1990s, Canada emerged as the largest North American producer of green- house tomatoes, a prominence it never attained in the fresh field tomato industry. The United States and Mexico have also become important green- house tomato producers, consistent with their long dominance in North Amer- ican fresh field tomato production. Greenhouse tomatoes have changed the look of U.S. retail tomato sales, where they now account for 37 percent of the quantity sold of fresh tomatoes. While the primary U.S. fresh field tomato product, the mature green tomato, long dominated retail sales, its share has decreased significantly due to the growth of greenhouse tomatoes. The U.S. mature green tomato industry is now more dependent on the continuing growth of the foodservice market, which generally prefers its product. Keywords: Greenhouse tomatoes, field tomatoes, mature green tomatoes, United States, Canada, Mexico, market integration, product differentiation, seasonality in production. Acknowledgments The authors wish to thank the many growers, marketers, and fresh tomato industry representatives in the United States, Canada, and Mexico who generously contributed their time and expertise in helping us better our understanding of the greenhouse tomato industry and its impact on the field tomato industry. In addition, we turned to a small group of people repeat- edly for insight into the industry, and we would like to acknowledge their willingness to help us in this endeavor. -

Nielsen, Inds & Symbols, MAT WE 24.01.15 Countlines Category Market Rankings 51 - 100

Countlines Category Market Rankings 01 - 50 Value Sales Value ROS (Wtd) 1 CADBURY TWIRL £9,970,617 £4.88 2 SNICKERS DUO KINGSIZE BAR £8,169,690 £4.23 3 SNICKERS £8,095,552 £3.91 4 MARS £7,960,719 £3.85 5 KINDER BUENO CLASSIC £7,193,415 £3.94 6 CADBURY WISPA £6,808,004 £3.45 7 KIT KAT ORIGINAL 4 FINGER £5,896,238 £3.18 8 BOOST GLUCOSE £5,606,595 £2.93 9 CADBURY DOUBLE DECKER £5,596,071 £2.77 10 MARS DUO KINGSIZE BAR £5,532,976 £3.01 11 CADBURY CRUNCHIE £5,057,457 £2.56 12 BOUNTY MILK £4,966,953 £2.44 13 TWIX ORIGINAL £4,942,220 £2.61 14 MALTESERS £4,861,405 £2.41 15 CADBURY DAIRY MILK £4,707,792 £2.56 16 CADBURY PICNIC £4,536,570 £2.44 17 MALTESERS TEASERS BAR £4,477,822 £2.61 18 CADBURY STAR BAR £4,463,279 £2.42 19 TWIX XTRA £4,385,281 £3.17 20 MILKY WAY MAGIC STARS £4,371,408 £2.37 21 KINDER BUENO WHITE £4,361,366 £3.20 22 FRYS TURKISH DELIGHT £4,348,354 £2.50 23 CADBURY WISPA GOLD £4,339,120 £2.83 24 SMARTIES £4,323,495 £2.17 25 MILKYBAR £4,183,795 £2.31 26 GALAXY RIPPLE £4,178,822 £2.34 27 YORKIE MILK £4,167,169 £2.37 28 CADBURY FLAKE £4,165,797 £2.32 29 CADBURY DAIRY MILK FREDDO £3,860,895 £2.14 30 MILKY WAY £3,850,414 £2.35 31 AERO PEPPERMINT £3,751,891 £2.29 32 KIT KAT CHUNKY £3,696,204 £2.22 33 GALAXY MILK £3,613,268 £2.13 34 MUNCHIES ORIGINAL £3,330,351 £2.07 35 KIT KAT CHUNKY PEANUT BUTTER £3,328,803 £2.46 36 BOUNTY DARK £3,197,116 £1.99 37 DAIM £3,158,971 £2.10 38 MILKYBAR BUTTONS £3,082,719 £1.87 39 FRYS CHOCOLATE CREAM £3,039,479 £2.30 40 CADBURY DAIRY MILK CARAMEL £2,801,104 £1.87 41 TERRYS CHOCOLATE ORANGE MILK £2,767,264 -

Sweets and Chocolates for School

Sweets and Chocolates for school Thank you for taking time to read or reference this list. Allergies can be fatal, but they can be managed and risks reduced with help and consideration. Please always read the label. Red Light These sweets Cadbury's: Brunch Bar Peanut Protein; Chocolate coated – Do not CONTAIN peanuts; Little Robins Daim variety; Lion Peanut bar; Picnic; take to peanuts and/or Star Bar; Dairy Milk Bags/Bars: Big Taste Toffee / Classic school nuts and are Collection / Cookie Nut Crunch / Daim / Fruit & Nut, Big Taste DANGEROUS / Nutty Caramel / Toffee / Triple Chocolate Sensation / Peanut to pupils who Caramel Crisp / Whole Nut. are allergic to Others: All chewing/snacking nuts; Aero Bliss Mix; peanuts and Celebrations; Galaxy Darker with Hazelnut; Green & Blacks nuts. Almond & Hazelnut varieties; Jordan’s cereal bars – all kinds; Kinder – Happy hippo / Bueno (all, inc Bon bons); KitKat – chunky & bites Peanut Butter / Senses variety box / collection box; Lindt chocolate & hazelnut bar, M&M's – peanut, hazelnut and caramel varieties; Marzipan; Milka (all); Milk Tray; Nougat; Nutella; Nut flavoured treats; Quality Street; Ritter Sport; Reese’s (all); Roses; Snickers; Sugared Almonds; Toblerone (all); Thornton’s; Topic. Amber Light These sweets Bassett's: Cherry Drops; Everton Mints; Fruit Bon Bons; Mint – Okay to MAY CONTAIN Favourites; Murray Mints; Sherbet Lemons. take to traces of Cadbury's: Boost; Bourneville / Bourneville orange; Brunch school peanuts and/or Bars Raisin and Choc Chip; Double Decker; Little Robins; Lion nuts or be Heads Bag; Dairy Milk bags/bars: Caramel Nibbles / Choca- labelled they latte / Crunchie bits / Dairy Milk / Little bars / Marvellous are made in a creations Jelly Popping / Medley Biscuit and Fudge / Merry factory that Christmas / Oreo / Oreo Mint / Premier League / Premier Pitch uses peanuts / Raspberry Shortcake / Simply the Zest / Tiffin / Winter and/or nuts. -

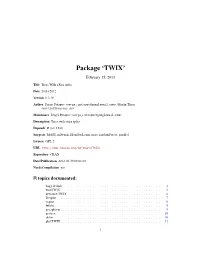

Package 'TWIX'

Package ‘TWIX’ February 15, 2013 Title Trees WIth eXtra splits Date 28.03.2012 Version 0.2.19 Author Sergej Potapov <[email protected]>, Martin Theus <[email protected]> Maintainer Sergej Potapov <[email protected]> Description Trees with extra splits Depends R (>= 1.8.0) Suggests MASS, mlbench, ElemStatLearn, rpart, randomForest, parallel License GPL-2 URL http://www.rosuda.org/software/TWIX/ Repository CRAN Date/Publication 2012-03-29 08:01:03 NeedsCompilation yes R topics documented: bagg.default . .2 bootTWIX . .3 deviance.TWIX . .6 Devplot . .7 export . .8 fullrks . .9 get.splitvar . .9 get.tree . 10 olives ............................................ 10 plot.TWIX . 11 1 2 bagg.default predict.TWIX . 12 print.id.tree . 13 print.single.tree . 14 print.TWIX . 15 scree.plot . 15 splitt . 16 splitt.padj . 17 summary.TWIX . 18 trace.plot . 18 tune.TWIX . 19 TWIX............................................ 21 Index 25 bagg.default Predictions from TWIX’s or Bagging Trees Description Prediction of a new observation based on multiple trees. Usage ## Default S3 method: bagg(object,newdata = NULL, sq=1:length(object$trees), aggregation = "weighted", type = "class", ...) ## S3 method for class ’TWIX’ bagg(object,...) ## S3 method for class ’bootTWIX’ bagg(object,...) Arguments object object of classes TWIX or bootTWIX. newdata a data frame of new observations. sq Integer vector indicating for which trees predictions are required. aggregation character string specifying how to aggregate. There are three ways to aggregate the TWIX trees. One of them is the class majority voting (aggregation="majority"), another method is the weighted aggregation (aggregation="weighted"). type character string indicating the type of predicted value returned. -

Top Challenges from the First Practical Online Controlled Experiments Summit

Appears in the June 2019 issue of SIGKDD Explorations Volume 21, Issue 1 https://bit.ly/OCESummit1 Top Challenges from the first Practical Online Controlled Experiments Summit Somit Gupta (Microsoft)1, Ronny Kohavi (Microsoft) 2, Diane Tang (Google) 3, Ya Xu (LinkedIn) 4, Reid Andersen (Airbnb), Eytan Bakshy (Facebook), Niall Cardin (Google), Sumitha Chandran (Lyft), Nanyu Chen (LinkedIn), Dominic Coey (Facebook), Mike Curtis (Google), Alex Deng (Microsoft), Weitao Duan (LinkedIn), Peter Forbes (Netflix), Brian Frasca (Microsoft), Tommy Guy (Microsoft), Guido W. Imbens (Stanford), Guillaume Saint Jacques (LinkedIn), Pranav Kantawala (Google), Ilya Katsev (Yandex), Moshe Katzwer (Uber), Mikael Konutgan (Facebook), Elena Kunakova (Yandex), Minyong Lee (Airbnb), MJ Lee (Lyft), Joseph Liu (Twitter), James McQueen (Amazon), Amir Najmi (Google), Brent Smith (Amazon), Vivek Trehan (Uber), Lukas Vermeer (Booking.com), Toby Walker (Microsoft), Jeffrey Wong (Netflix), Igor Yashkov (Yandex) ABSTRACT 1.1 First Practical Online Controlled Online controlled experiments (OCEs), also known as A/B tests, Experiments Summit, 2018 have become ubiquitous in evaluating the impact of changes made To understand the top practical challenges in running OCEs at to software products and services. While the concept of online scale, representatives with experience in large-scale controlled experiments is simple, there are many practical experimentation from thirteen different organizations (Airbnb, challenges in running OCEs at scale and encourage further Amazon, Booking.com, Facebook, Google, LinkedIn, Lyft, academic and industrial exploration. To understand the top Microsoft, Netflix, Twitter, Uber, Yandex, and Stanford practical challenges in running OCEs at scale, representatives with University) were invited to the first Practical Online Controlled experience in large-scale experimentation from thirteen different Experiments Summit. -

Sugar Content Guide

66 Station Road Petersfield Hampshire GU32 3ET Tel: 01730 263092 Sugar Content Guide Email: [email protected] Web: www.sixtysixdental.uk PRODUCT AMOUNT OF PRODUCT TEASPOONS OF SUGAR BISCUITS Chocolate Biscuits 2 Biscuits 1 ½ Chocolate Digestives 1 Biscuit 1 ½ Cream Crackers 1 Biscuit Trace Custard Cream 2 Biscuits 1 ½ Ginger Nuts 2 Biscuits 1 ½ Jaffa Cakes 1 Biscuit 1 ½ Rich Tea Biscuits 1 Biscuit ½ Ritz 5 Biscuits ¼ Shortcake 2 Biscuits 1 Wheatmeal Biscuits 1 Small Biscuit ½ CONFECTIONERY Aero 1 Bar 3 ½ Boiled sweets 1 Packet 24 Bournville 2 Pieces 3 ¾ Bubble gum 1 Packet 6 ½ Milk Chocolate 1 Small Bar 8 Plain Chocolate 1 Small Bar 3 ½ Crunchie 1 Small Bar 6 Dolly Mixtures 1 Packet 6 Double Decker 1 Bar 20 ½ Drifter 1 Bar 6 Fruit Gums 1 Tube 6 ½ Fruit Pastilles 1 Tube 3 Galaxy 1 Bar 6 ¼ Kit Kat 1 Bar 3 ¼ Liquorice allsorts 1 Small Box 3 ¼ Lion Bar 1 Bar 17 ¾ Maltesers 1 Packet 5 ½ Mars 1 Bar 2 ½ Milky Way 1 Bar 5 Picnic 1 Bar 1 ½ Polo Mints 1 Tube 5 Rolos 1 Tube 5 ½ Smarties 1 Tube 4 ¼ Snickers 1 Bar 3 ½ Toffees 1 4oz Bag 20 Topic 1 Bar 3 ¾ Twix 1 Bar 3 ½ Turkish Delight 1 Bar 7 ¼ Yorkie 1 Bar 5 ¾ SOFT DRINKS Blackcurrant cordial 1 Glass 5 Coca Cola 1 Can 7 Ginger Beer 1 Can 7 Lemonade 1 Glass 3 ½ Lucozade 1 Glass 7 ¼ Orange Squash 1 Glass 2 ½ Ribena 1 Glass 5 Slush Puppy 1 Small cup 6 ¼ Tizer 1 Glass 4 ¼ Tonic Water 1 Medium bottle 4 SPREADS Chocolate 2 Teaspoons 2 ¼ Honey 2 Teaspoons 2 ¼ Jam 2 Teaspoons 2 Lemon Curd 2 Teaspoons 2 Marmalade 2 Teaspoons 2 ¼ Mincemeat 2 Teaspoons 3 Peanut Butter 3 Teaspoons ¼ Golden Syrup 2 Teaspoons 2 ¼ BEVERAGES Bournvita 3 Teaspoons 2 Camp Coffee 3 Teaspoons 1 Drinking Chocolate 3 Teaspoons 2 ½ Horlicks 3 Teaspoons 1 Ovaltine 3 Teaspoons 1 SAUCES PICKLES ETC. -

Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Mars 2020 Mission

Availability of the Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Mars 2020 Mission NASA will maintain a website that provides the public with the most up-to-date project information, including electronic copies of the EIS, as they are made available. The website may be accessed at http://www.nasa.gov/agency/nepa/mars2020eis Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Mars 2020 Mission FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT FOR THE MARS 2020 MISSION ABSTRACT LEAD AGENCY: National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, DC 20546 COOPERATING AGENCY: U.S. Department of Energy Washington, DC 20585 POINT OF CONTACT George Tahu FOR INFORMATION: Planetary Science Division Science Mission Directorate NASA Headquarters Washington, DC 20546 (202) 358-4800 DATE: November 2014 This Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) has been prepared by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969, as amended, to assist in the decision-making process for the proposed Mars 2020 mission. This Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) is a tiered document (Tier 2 EIS) under NASA’s Programmatic EIS for the Mars Exploration Program. The Proposed Action addressed in this FEIS is to continue preparations for and implementation of the Mars 2020 mission. The Mars 2020 spacecraft would be launched on an expendable launch vehicle during a launch opportunity from July through August 2020. The Mars 2020 spacecraft would deliver a large, mobile science laboratory (rover) with advanced instrumentation to a scientifically interesting location on the surface of Mars early in 2021. The design of the Mars 2020 spacecraft and rover would be based upon and similar to that used in the 2011 Mars Science Laboratory Mission, including the use of a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator. -

Traveling with People and Animal Power Introduction Big Ideas

Topic of Study – Traveling with People and Animal Power To introduce a series of topics of study related to travel, we begin by learning about traveling with people and animal power. People power includes walking, jogging and running, and pedaling, pushing and pulling wheeled vehicles. Animal power includes riding animals such as horses, camels and donkeys. Animals can also pull wagons and carts. Donkeys can carry things on their backs. Children can easily relate to all of these means of travel and will enjoy learning about traveling with people and animal power. Introduction Here are four big ideas about traveling with people and animal power you can help children explore: We can travel on foot (walking, running, jogging, skipping) We can travel by pushing, pulling and pedaling Wheels make it easy for us to travel Big Ideas Animals help us travel • Pictures that include people walking, running, jogging, riding unicycles, bicycles, tricycles, roller skating, ice skating, rollerblading, water and snow skiing, pulling wagons, pushing wheelbarrows, riding horses, camels and donkeys. Note: Consider searching Microsoft Clip Art or Google Images for pictures. • Pictures of bicycles, tricycles, roller skates, ice skates, rollerblades, wagons, wheelbarrows, skies, horses, camels and donkeys • Children’s books about traveling with people and animal power: Materials to On the Go by Ann Morris, photographs by Ken Heyman Collect and We’re Going on a Bear Hunt by Michael Rosen, illustrated by Helen Oxenbury Curious George Rides a Bike by H. A. Rey Make • Felt or Magnetic Board • Locate at A Story a Month on the Arkansas Better Beginnings website: Storytelling figures (felt or magnetic) for the book, We’re Going on a Bear Hunt Storytelling figures (felt or magnetic) for the book, Ask Mr.