Why Fair Use Should Extend to Fan-Based Activities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'expérience De Création De Jeux Vidéo En Amateur Travailler Son

Université de Liège Faculté de Philosophie et Lettres Département Médias, Culture et Communication L’expérience de création de jeux vidéo en amateur Travailler son goût pour l’incertitude Thèse présentée par Pierre-Yves Hurel en vue de l’obtention du titre de Docteur en Information et Communication sous la direction de Christine Servais Année académique 2019-2020 À Anne-Lyse, à notre aventure, à nos traversées, à nos horizons. À Charlotte, à tes cris de l’oie, à tes sourires en coin, à tes découvertes. REMERCIEMENTS Écrire une thèse est un acte pétri d’incertitudes, que l’auteur cherche à maîtriser, cadrer et contrôler. J’ai eu le bonheur d’être particulièrement bien accompagné dans cette pratique du doute. Seul face à mon document, j’étais riche de toutes les discussions qui ont jalonné mes années de doctorat. Je souhaite particulièrement remercier mes interlocuteurs pour leur générosité : - Christine Servais, pour sa direction minutieuse, sa franchise, sa bienveillance, ses conseils et son écoute. - Les membres du jury pour avoir accepté de me livrer leur analyse du présent travail. - Tous les membres du Liège Game Lab pour leur intelligence dans leur participation à notre collectif de recherche, pour leur capacité à échanger de manière constructive et pour leur humour sans égal. Merci au Docteure Barnabé (chercheuse internationale et coauteure de cafés-thèse fondateurs), au Docteure Delbouille (brillante sitôt qu’on l’entend), au Docteur Dupont (titulaire d’un double doctorat en lettres modernes et en élégance), au Docteur Dozo (dont le sens du collectif a tant permis), au futur Docteur Krywicki (prolifique en tout domaine), au futur Docteur Houlmont (dont je ne connais qu’un défaut) et au futur Docteur Bashandy (dont le vécu et les travaux incitent à l’humilité). -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

The Origins of the Magical Girl Genre Note: This First Chapter Is an Almost

The origins of the magical girl genre Note: this first chapter is an almost verbatim copy of the excellent introduction from the BESM: Sailor Moon Role-Playing Game and Resource Book by Mark C. MacKinnon et al. I took the liberty of changing a few names according to official translations and contemporary transliterations. It focuses on the traditional magical girls “for girls”, and ignores very very early works like Go Nagai's Cutie Honey, which essentially created a market more oriented towards the male audience; we shall deal with such things in the next chapter. Once upon a time, an American live-action sitcom called Bewitched, came to the Land of the Rising Sun... The magical girl genre has a rather long and important history in Japan. The magical girls of manga and Japanese animation (or anime) are a rather unique group of characters. They defy easy classification, and yet contain elements from many of the best loved fairy tales and children's stories throughout the world. Many countries have imported these stories for their children to enjoy (most notably France, Italy and Spain) but the traditional format of this particular genre of manga and anime still remains mostly unknown to much of the English-speaking world. The very first magical girl seen on television was created about fifty years ago. Mahoutsukai Sally (or “Sally the Witch”) began airing on Japanese television in 1966, in black and white. The first season of the show proved to be so popular that it was renewed for a second year, moving into the era of color television in 1967. -

In the Matter of the February 6, 2021 Police-Involved Shooting in Gaithersburg, Maryland

In the matter of the February 6, 2021 police-involved shooting in Gaithersburg, Maryland. Pursuant to an agreement between our two offices, the Office of the State’s Attorney for Howard County is hereby providing this written memorandum detailing our investigation and the conclusions we reached regarding a police-involved shooting that occurred on February 6, 2021 in the 6000 block of Olney Laytonsville Road in Gaithersburg. Timeline of Investigation On the morning of Saturday, February 6, 2021, Howard County State’s Attorney Office received an email from Detective Eric Glass of the Montgomery County Police Department – Homicide Section. DSA Sandmann called Detective Glass on the phone and was informed by Glass that Montgomery County had a police-involved shooting in Gaithersburg, Maryland. Glass indicated that an off-duty sheriff deputy had shot and killed a person who had been running cars off the road with his vehicle. Upon locating the suspect, the deputy approached him. Glass indicated the suspect attacked the deputy with a bat or stick of some sort before being shot. The initial information revealed that several 911 calls came in at just after 8 a.m. The callers told the 911 dispatcher that a multiple vehicle accident (airbags deployed) had just occurred in the 6000 block of Olney Laytonsville Road in Gaithersburg. Police and paramedics were immediately dispatched to the scene. The callers went on to say a person driving a Volkswagen had caused one vehicle to swerve off the road into a pole before continuing on and hitting a second vehicle in a head-on collision. -

Piracy Or Productivity: Unlawful Practices in Anime Fansubbing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aaltodoc Publication Archive Aalto-yliopisto Teknillinen korkeakoulu Informaatio- ja luonnontieteiden tiedekunta Tietotekniikan tutkinto-/koulutusohjelma Teemu Mäntylä Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Diplomityö Espoo 3. kesäkuuta 2010 Valvoja: Professori Tapio Takala Ohjaaja: - 2 Abstract Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Over a short period of time, Japanese animation or anime has grown explosively in popularity worldwide. In the United States this growth has been based on copyright infringement, where fans have subtitled anime series and released them as fansubs. In the absence of official releases fansubs have created the current popularity of anime, which companies can now benefit from. From the beginning the companies have tolerated and even encouraged the fan activity, partly because the fans have followed their own rules, intended to stop the distribution of fansubs after official licensing. The work explores the history and current situation of fansubs, and seeks to explain how these practices adopted by fans have arisen, why both fans and companies accept them and act according to them, and whether the situation is sustainable. Keywords: Japanese animation, anime, fansub, copyright, piracy Tiivistelmä Piratismia vai tuottavuutta: laittomat toimintatavat animen fanikäännöksissä Japanilaisen animaation eli animen suosio maailmalla on lyhyessä ajassa kasvanut räjähdysmäisesti. Tämä kasvu on Yhdysvalloissa perustunut tekijänoikeuksien rikkomiseen, missä fanit ovat tekstittäneet animesarjoja itse ja julkaisseet ne fanikäännöksinä. Virallisten julkaisujen puutteessa fanikäännökset ovat luoneet animen nykyisen suosion, jota yhtiöt voivat nyt hyödyntää. Yhtiöt ovat alusta asti sietäneet ja jopa kannustaneet fanien toimia, osaksi koska fanit ovat noudattaneet omia sääntöjään, joiden on tarkoitus estää fanikäännösten levitys virallisen lisensoinnin jälkeen. -

Manga Book Club Handbook

MANGA BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for manga! STAFF COMIC Director’sBOOK LEGAL Note Charles Brownstein, Executive Director DEFENSE FUND Alex Cox, Deputy Director Everything is changing in 2016, yet the familiar challenges of the past continueBetsy to Gomez, Editorial Director reverberate with great force. This isn’t just true in the broader world, but in comics,Maren Williams, Contributing Editor Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor too. While the boundaries defining representation and content in free expression are protectingexpanding, wethe continue freedom to see to biasedread comics!or outmoded Our viewpoints work protects stifling those advances.Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- STAFF As you’ll see in this issue of CBLDF Defender, we are working on both ends of the Charles Brownstein, Executive Director torsspectrum who byface providing the threat vital educationof censorship. about the We people monitor whose worklegislation expanded free exBOARD- Alex OF Cox, DIRECTORS Deputy Director pression while simultaneously fighting all attempts to censor creative work in comics.Larry Marder,Betsy Gomez, President Editorial Director and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. Maren Williams, Contributing Editor In this issue, we work the former end of the spectrum with a pair of articles spotlightMilton- Griepp, Vice President We create resources that promote understanding of com- Jeff Abraham,Caitlin McCabe,Treasurer Contributing Editor ing the pioneers who advanced diverse content. On page 10, “Profiles in Black Cartoon- Dale Cendali,Robert SecretaryCorn-Revere, Legal Counsel icsing” and introduces the rights you toour some community of the cartoonists is guaranteed. -

Anime Expo Lite 2021 Sweepstakes Official Rules

ANIME EXPO LITE 2021 SWEEPSTAKES OFFICIAL RULES 1. Official Rules. The Anime Expo Lite 2021 Sweepstakes (the “Promotion”) is subject to these Official Rules, except as expressly stated otherwise. No purchase necessary. A purchase does not improve your chances of winning. Void where prohibited. The Sweepstakes is sponsored by Society for the Promotion of Japanese Animation, 1522 Brookhollow Dr. Suite 1, Santa Ana, CA 92705 (the “Sponsor”). 2. Eligibility. The Sweepstakes is open to legal residents of the United States (but excluding U.S. military installations in foreign countries and all other U.S. territories and possessions), who are 18 years of age or older at the start of the Promotion (“Entrant”). By participating in the Sweepstakes, Entrant agrees to be fully and unconditionally bound by these Official Rules and the decisions of Sponsor. 3. Privacy. The information you provide in your entry will be used for administering this Promotion and for marketing purposes in accordance with Sponsor’s privacy policy found here: http://www.anime-expo.org/plan/policies/. 4. Sweepstakes Period. The Sweepstakes begins at 12:00 p.m PDT on June 25, 2021 and ends at 12:00 p.m. PDT on July 16, 2021 (the "Promotion Period"). 1. How to Enter the Sweepstakes. During the Sweepstakes Period, you can enter the Sweepstakes through the following methods: a. Purchase: You may purchase an online pass for Anime Expo Lite 2021 from https://www.tixr.com/groups/animeexpolite/events/anime-expo-lite-2021- benefitting-hate-is-a-virus-23015 (“Website”); Note: All online passes purchased prior to the Sweepstakes Period are also eligible to enter. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

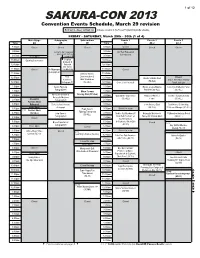

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture David Endresak [email protected]

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2006 Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture David Endresak [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Recommended Citation Endresak, David, "Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture" (2006). Senior Honors Theses. 322. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/322 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture Degree Type Open Access Senior Honors Thesis Department Women's and Gender Studies First Advisor Dr. Gary Evans Second Advisor Dr. Kate Mehuron Third Advisor Dr. Linda Schott This open access senior honors thesis is available at DigitalCommons@EMU: http://commons.emich.edu/honors/322 GIRL POWER: FEMININE MOTIFS IN JAPANESE POPULAR CULTURE By David Endresak A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Eastern Michigan University Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors in Women's and Gender Studies Approved at Ypsilanti, Michigan, on this date _______________________ Dr. Gary Evans___________________________ Supervising Instructor (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Kate Mehuron_________________________ Honors Advisor (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Linda Schott__________________________ Dennis Beagan__________________________ Department Head (Print Name and have signed) Department Head (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Heather L. S. Holmes___________________ Honors Director (Print Name and have signed) 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Printed Media.................................................................................................. -

Lexis Practice Advisor Intellectual Property & Technology Determining

Lexis Practice Advisor® is a comprehensive practical guidance resource for attorneys who handle transactional matters, including “how to” information, model forms and on point cases, codes and legal analysis. The Intellectual Property & Technology offering contains access to a unique collection of expertly authored content, continuously updated to help you stay up to speed on leading practice trends. The following is a practical guidance excerpt from the topic Copyright Ownership & Registration. Lexis Practice Advisor Intellectual Property & Technology Determining Copyright Ownership by Jeremy S. Goldman, Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz PC Jeremy S. Goldman is counsel in the Litigation Group of Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz PC, where he focuses on intellectual property, entertainment and privacy law for clients in the media, entertainment, advertising and technology spaces. Overview Copyright protection is given to authors of original and expressive works , including literary, musical, dramatic, sculptural, and certain other categories of works, which are fixed in a tangible medium. Although the author of a copyrighted work is generally also the creator of the work, there are exceptions to this, such as works made for hire and works jointly authored by more than one person. A copyright in a derivative work protects only the new and original elements added to preexisting work; the author of the derivative work has no ownership interest in the preexisting work. The ownership of a copyright may be transferred or assigned, in whole or in part. That is, each of the exclusive rights afforded a copyright owner under the Copyright Act may be owned and transferred separately. To the extent there are conflicting transfers, the prior transferee will have priority over any subsequent transferee so long as the transfer is recorded within one month of execution (for transfers made in the United States), or at any time prior to recordation of the transfer to a subsequent transferee. -

An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests Amanda Schreyer

Cybaris® Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 3 2015 An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests Amanda Schreyer Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cybaris Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Schreyer, Amanda (2015) "An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests," Cybaris®: Vol. 6: Iss. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cybaris/vol6/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cybaris® by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Schreyer: An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balanci Published by Mitchell Hamline Open Access, 2015 1 Cybaris®, Vol. 6, Iss. 1 [2015], Art. 3 AN OVERVIEW OF LEGAL PROTECTION FOR FICTIONAL CHARACTERS: BALANCING PUBLIC AND PRIVATE INTERESTS † AMANDA SCHREYER I. Fictional Characters and the Law .............................................. 52! II. Legal Basis for Protecting Characters ...................................... 53! III. Copyright Protection of Characters ........................................ 57! A. Literary Characters Versus Visual Characters ............... 60! B. Component Parts of Characters Can Be Separately Copyrightable ................................................................