Census of the Birds of Clipperton Island, 1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country of Citizenship Active Exchange Visitors in 2017

Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 Active Exchange Visitors Country of Citizenship in 2017 AFGHANISTAN 418 ALBANIA 460 ALGERIA 316 ANDORRA 16 ANGOLA 70 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 29 ARGENTINA 8,428 ARMENIA 325 ARUBA 1 ASHMORE AND CARTIER ISLANDS 1 AUSTRALIA 7,133 AUSTRIA 3,278 AZERBAIJAN 434 BAHAMAS, THE 87 BAHRAIN 135 BANGLADESH 514 BARBADOS 58 BASSAS DA INDIA 1 BELARUS 776 BELGIUM 1,938 BELIZE 55 BENIN 61 BERMUDA 14 BHUTAN 63 BOLIVIA 535 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 728 BOTSWANA 158 BRAZIL 19,231 BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS 3 BRUNEI 44 BULGARIA 4,996 BURKINA FASO 79 BURMA 348 BURUNDI 32 CAMBODIA 258 CAMEROON 263 CANADA 9,638 CAPE VERDE 16 CAYMAN ISLANDS 1 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 27 CHAD 32 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 CHILE 3,284 CHINA 70,240 CHRISTMAS ISLAND 2 CLIPPERTON ISLAND 1 COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS 3 COLOMBIA 9,749 COMOROS 7 CONGO (BRAZZAVILLE) 37 CONGO (KINSHASA) 95 COSTA RICA 1,424 COTE D'IVOIRE 142 CROATIA 1,119 CUBA 140 CYPRUS 175 CZECH REPUBLIC 4,048 DENMARK 3,707 DJIBOUTI 28 DOMINICA 23 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 4,170 ECUADOR 2,803 EGYPT 2,593 EL SALVADOR 463 EQUATORIAL GUINEA 9 ERITREA 10 ESTONIA 601 ETHIOPIA 395 FIJI 88 FINLAND 1,814 FRANCE 21,242 FRENCH GUIANA 1 FRENCH POLYNESIA 25 GABON 19 GAMBIA, THE 32 GAZA STRIP 104 GEORGIA 555 GERMANY 32,636 GHANA 686 GIBRALTAR 25 GREECE 1,295 GREENLAND 1 GRENADA 60 GUATEMALA 361 GUINEA 40 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 GUINEA‐BISSAU -

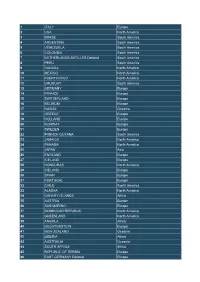

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania Prepared for the US Department of Defense’s Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance May 2020 Written by: Jonah Bhide Grace Frazor Charlotte Gorman Claire Huitt Christopher Zimmer Under the supervision of Dr. Joshua Busby 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 United States 8 Oceania 22 China 30 Australia 41 New Zealand 48 France 53 Japan 61 Policy Recommendations for US Government 66 3 Executive Summary Research Question The current strategic landscape in Oceania comprises a variety of complex and cross-cutting themes. The most salient of which is climate change and its impact on multilateral political networks, the security and resilience of governments, sustainable development, and geopolitical competition. These challenges pose both opportunities and threats to each regionally-invested government, including the United States — a power present in the region since the Second World War. This report sets out to answer the following questions: what are the current state of international affairs, complexities, risks, and potential opportunities regarding climate security issues and geostrategic competition in Oceania? And, what policy recommendations and approaches should the US government explore to improve its regional standing and secure its national interests? The report serves as a primer to explain and analyze the region’s state of affairs, and to discuss possible ways forward for the US government. Given that we conducted research from August 2019 through May 2020, the global health crisis caused by the novel coronavirus added additional challenges like cancelling fieldwork travel. However, the pandemic has factored into some of the analysis in this report to offer a first look at what new opportunities and perils the United States will face in this space. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

GENERAL AGREEMENT on ^ TARIFFS and TRADE *> *****1958

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON ^ TARIFFS AND TRADE *> *****1958 Limited Distribution APPLICATION OF THE GENERAL AGREEMENT Territories to which the Agreement is applied Annexed hereto is a list of the contracting parties and of the territories (according to information available to the secretariat) in respect of which the application of the Agreement has been made effective. This list is a revision of that which appeared in document G/5 under date of 17 March 1952. If there are any inaccuracies in this list, the contracting parties concerned are requested to notify the Executive Secretary not later than 1 October 1958 so that a revised list can be issued, if necessary, before the opening of the Thirteenth Session* L/843 Paee 2 Contracting parties to GATT and territories In respeot ot which the application of the Agreement has been made affective AUSTRALIA (Including Tasmania) AUSTRIA BELGIUM BELGIAN CONGO RUANDA-URUNDI (Trust Territory) BRAZIL (Including islands: Fernando de Noronha (including Rocks of Sao Pedro, Sao Paolo, Atoll das Rocas) Trinidad and Martim Vas) BURMA CANADA CEYLON CHILE (Including the islands of: Juan Fernandez group, Easter Islands, Sala y Gomez, San Feliz, San Ambrosio and western part of Tierra del Fuego) CUBA (Including Isle of Pines and some smaller islands) CZECHOSLOVAKIA DENMARK (Including Greenland and the Island of Disko, Faroe Islands, Islands of Zeeland, Funen, Holland, Falster, Bornholm and some 1700 small islands) DOMINICAN REPUBLIC (Including islands: Saona, Catalina, Beata and some smaller ones) FINLAND FRANCE (Including Corsica and Islands off the French Coast, the Saar and the principality of Monaco)! ALGERIA CAMEROONS (Trust Territory) FRENCH EQUATORIAL AFRICA FRENCH GUIANA (Including islands of St. -

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index A (General) Abeokuta: the Alake of Abram, Morris B.: see A (General) Abruzzi: Duke of Absher, Franklin Roosevelt: see A (General) Adams, C.E.: see A (General) Adams, Charles, Dr. D.F., C.E., Laura Franklin Delano, Gladys, Dorothy Adams, Fred: see A (General) Adams, Frederick B. and Mrs. (Eilen W. Delano) Adams, Frederick B., Jr. Adams, William Adult Education Program Advertisements, Sears: see A (General) Advertising: Exhibits re: bill (1944) against false advertising Advertising: Seagram Distilleries Corporation Agresta, Fred Jr.: see A (General) Agriculture Agriculture: Cotton Production: Mexican Cotton Pickers Agriculture: Department of (photos by) Agriculture: Department of: Weather Bureau Agriculture: Dutchess County Agriculture: Farm Training Program Agriculture: Guayule Cultivation Agriculture: Holmes Foundry Company- Farm Plan, 1933 Agriculture: Land Sale Agriculture: Pig Slaughter Agriculture: Soil Conservation Agriculture: Surplus Commodities (Consumers' Guide) Aircraft (2) Aircraft, 1907- 1914 (2) Aircraft: Presidential Aircraft: World War II: see World War II: Aircraft Airmail Akihito, Crown Prince of Japan: Visit to Hyde Park, NY Akin, David Akiyama, Kunia: see A (General) Alabama Alaska Alaska, Matanuska Valley Albemarle Island Albert, Medora: see A (General) Albright, Catherine Isabelle: see A (General) Albright, Edward (Minister to Finland) Albright, Ethel Marie: see A (General) Albright, Joe Emma: see A (General) Alcantara, Heitormelo: see A (General) Alderson, Wrae: see A (General) Aldine, Charles: see A (General) Aldrich, Richard and Mrs. Margaret Chanler Alexander (son of Charles and Belva Alexander): see A (General) Alexander, John H. Alexitch, Vladimir Joseph Alford, Bradford: see A (General) Allen, Mrs. Idella: see A (General) 2 Allen, Mrs. Mary E.: see A (General) Allen, R.C. -

Brachyura of the Pacific Coast of America Brachyrhyncha: Portunidae

n\oo ALLAN HANCOCK MONOGRAPHS IN MARINE BIOLOGY NUMBER 1 BRACHYURA OF THE PACIFIC COAST OF AMERICA BRACHYRHYNCHA: PORTUNIDAE BY JOHN S. GARTH AND W. STEPHENSON LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA PRINTED FOR THE ALLAN HANCOCK FOUNDATION UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 1966 Kff' ALLAN HANCOCK MONOGRAPHS IN MARINE BIOLOGY NUMBER 1 BRACHYURA OF THE PACIFIC COAST OF AMERICA BRACHYRHYNCHA: PORTUNIDAE BY JOHN S. GARTH Allan Hancock Foundation and Department of Biological Sciences University of Southern California Los Angeles, California AND W. STEPHENSON Department of Zoology Ij nivcrsity of Queensland Brisbane, Australia I .OS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA PRINTED FOR THE ALLAN HANCOCK FOUNDATION UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 1966 ALLAN HANCOCK MONOGRAPHS IN MARINE BIOLOGY NUMBER 1 ISSUED: APRIL 29, 1966 PRICE: $4.50 THE ALLAN HANCOCK FOUNDATION UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Los ANGELES, CALIFORNIA TABLE OF CONTENTS General Discussion 1 Introduction 1 Source of Materials 2 Acknowledgment 2 Systematic Discussion 3 Method of Treatment 3 Historical Review 3 Analogous Atlantic Species 4 Explanation of Terms 8 Color Notes 9 Abbreviations 9 Family Portunidae 9 Subfamily Macropipinae 12 Genus Ovalipes 12 Ovalipes punctatus (de Haan) 12 Subfamily Portuninae 14 Genus Portunus 15 Portunus acuminatus (Stimpson) 17 Portunus angustus Rathbun 19 Portunus asper (A. Milne Edwards) 19 Portunus brevimanus (Faxon) 23 Portunus iridescens (Rathbun) 26 Portunus guaymasensis n. sp 29 Portunus stanfordi Rathbun 31 Portunus xantusii (Stimpson) 31 Portunus xantusii xantusii (Stimpson) 32 Portunus xantusii minimus (Rathbun) 35 Portunus xantusii affinis (Faxon) 38 Portunus tuberculatus (Stimpson) 40 Genus Callinectes 42 Callinectes arcuatus Ordway 43 Callinectes bellicosus (Stimpson) 47 Callinectes toxotes Ordway 50 Genus Arenaeus 52 Arenaeus mexicanus (Gerstaecker) 53 Genus Cronius 56 Cronius ruber (Lamarck) 57 Subfamily Podophthalminae 62 Genus Euphylax 63 Euphylax dovii Stimpson 64 Euphylax robustus A. -

The Role of the French Military on Key Issues for Oceania

Asia Pacific Bulletin The Role of the French Military on Key Issues for Oceania BY HELENE GOIRAN On February 14, 2018, in a statement before the House Armed Services Commiee, Admiral Harry B. Harris Jr, Commander, U.S. Pacific Command — who had been to New Caledonia in October 2017 — reminded listeners that “France has significant equies in the Indo‐Pacific” and declared that he “welcome[d] France’s growing involvement in the region.” Helene Goiran, member of Eight thousand French defense personnel are permanently located throughout the Indo‐Asia‐Pacific: 4,500 in the Indian Ocean, 2,800 in the Pacific Ocean and 700 sailors on deployment. The French the Maison de la Melanesie military in the Pacific operates two surveillance frigates, four patrol vessels, two mul‐mission ships, research group, explains five marime surveillance aircra, four taccal transport aircra, and seven helicopters. These forces that “France has the second ensure the protecon and safety of French territories, as well as the surveillance of exclusive economic zones (EEZ), contribute to the France’s acon at sea, and are involved in a number of largest EEZ in the world defense diplomacy and cooperaon acvies. They also play a role on issues that are key for the located mainly in the Pacific islands, especially environmental security, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HA/DR), Pacific, and is responsible and marime security including counter‐trafficking. for protecting the fragile France is present in the Pacific through it territories New Caledonia, French Polynesia, Wallis‐et‐ maritime environment and Futuna, and Clipperton Island. This makes it a power of the Pacific, with a concomitant responsibility its extensive fishing, to defend its sovereignty and guarantee the security of its cizens. -

Global Regions Structure

Global Regions Model* LATIN AMERICA/ NORTH AFRICA ASIA EUROPE OCEANIA CARIBBEAN AMERICA Angola Azerbaijan Åland Anguilla Canada American Ascension Bangladesh Albania Antigua and Barbuda St Pierre and Samoa Bassa da India Bhutan Andorra Argentina Miquelon Ashmore and Benin British Indian Ocean Armenia Aruba Puerto Rico Cartier Islands Botswana Territory Austria Bahamas United States of Australia Bouvet Island Brunei Darussalam Belarus Barbados America Baker Island Burkina Faso Cambodia Belgium Belize Coral Sea Burundi China Bosnia-Herzegovina Bermuda Islands Cameroon Christmas Island Bulgaria British Virgin Islands Cook Islands Cape Verde Cocos (Keeling) Channel Islands Bolivia Fiji Central African Republic Islands Croatia Brazil French Chad Cyprus Czech Republic Netherlands Antilles Polynesia Comoros Akrotiri Denmark Cayman Islands Guam Congo, Dem. Rep. of Dhekelia Estonia Chile Howland Island (aka Zaire) Georgia Faeroe Islands Clipperton Island Jarvis Island Congo, Republic of Heard and McDonald Finland Colombia Johnston Atoll Cote d’Ivoire Islands France Costa Rica Kingman Reef Equatorial Guinea Hong Kong SAR Germany Cuba Kiribati Eritrea India Gibraltar Curacao _____________ Marshall Islands Ethiopia Indonesia Greece Dominica MIDDLE Micronesia, Europa Island Japan Greenland Dominican Republic EAST Federated French Southern and Kazakhstan Guernsey Ecuador States of Antarctic Lands Kyrgyzstan Holy See El Salvador Afghanistan Midway Islands Gabon Lao People’s Dem. (aka Vatican City) Falkland Islands Algeria Nauru Gambia Rep. Hungary Grenada Bahrain New Caledonia Ghana Macau SAR Iceland Guatemala Djibouti New Zealand Glorioso Islands Malaysia Ireland Guadeloupe Egypt Niue Guinea Maldives Israel French Guiana Iran, Islamic Norfolk Island Guinea-Bissau Mongolia Isle of Man Guyana Rep. of Northern Mariana Juan de Nova Island Myanmar Italy Haiti Iraq Islands Kenya Nepal Jan Mayen Island Honduras Jordan Palau Lesotho Dem. -

Some Algae from Clipperton Island and the Danger Islands

Some Algae from Clipperton Island and the Danger Islands Item Type article Authors Dawson, E. Yale Download date 25/09/2021 22:34:01 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/20635 SOME ALGAE FROM CLIPPERTON ISLAND AND THE DANGER ISLANDS By E. Yale Dawson Fig. 1. Rhizoclonium proftmdum sp. nov., from the type collection. A, Habit of a young plant attached to two filaments of older plants, shuwing rhizoids, altachment~ and branches, X 20. B, Detail of a single mature cell showing stratitied walls and reticu late chloroplast, X 75. SOME ALGAE FROM CLIPPERTON ISLAND AND THE DANGER ISLANDS By E. YALE DAwso:\, Through the cooperation of Dr. Carl L. Huhbs the writer has received through the Scripps Institution of Oceanography two interesting collection~ of tropical Paci fie benthic algae, one from remote Clipperton Island, the easternmost coral atoll in the Pacific, and one from a depth of about 200 feet at Pukapuka in the Danger Island~, l"nion Group, about 400 mile~ northea~t of Samoa. These are reported on helow in turn. I am grateful to Dr. Isabella Ahbott for reading and criticizing this paper. Clipperton Island The algal vegetation of this solitary atoll is known only from the papers of Taylor (1939) and Dawson (1957). These reports list only 17 entities, including 6 species of Cyanophyta and 3 unsatisfactorily identified species of other groups. The present collections, made principally hy Messrs. C. Limbaugh, T. Chess, A. Hambly and Miss M.·H. Sachet on the recent Scripps Institution Expedition (August.September, 1958), are more ample than any previously available, and permit us to add 30 marine species and 14 terrestrial and fresh water species, making a total of 61 known from the atoll. -

Second Supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-List of North American Birds

A O U Check-listSupplement The Auk 117(3):847-858, 2000 FORTY-SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION CHECK-LIST OF NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS This first Supplementsince publication of the 7th Icterusprosthemelas, Lonchura cantans, and L. atricap- edition (1998)of the AOU Check-listof North American illa); (3) four speciesare changed(Caracara cheriway, Birdssummarizes changes made by the Committee Glaucidiumcostaricanum, Myrmotherula pacifica, Pica on Classification and Nomenclature between its re- hudsonia)and one added (Caracaralutosa) by splits constitutionin late 1998 and 31 January2000. Be- from now-extralimital forms; (4) four scientific causethe makeupof the Committeehas changed sig- namesof speciesare changedbecause of genericre- nificantly since publication of the 7th edition, it allocation (Ibycter americanus,Stercorarius skua, S. seemsappropriate to outline the way in which the maccormicki,Molothrus oryzivorus); (5) one specific currentCommittee operates. The philosophyof the name is changedfor nomenclaturalreasons (Baeolo- Committeeis to retain the presenttaxonomic or dis- phusridgwayi); (6) the spellingof five speciesnames tributional statusunless substantial and convincing is changedto make them gramaticallycorrect rela- evidenceis publishedthat a changeshould be made. tive to the genericname (Jacameropsaureus, Poecile The Committee maintains an extensiveagenda of atricapilla,P. hudsonica,P. cincta,Buarremon brunnein- potential actionitems, includingpossible taxonomic ucha);(7) oneEnglish name is changedto conformto -

Pacific Climate Update Coral Bleaching Heat Stress Analysis and Seasonal Guidance Through August 2018

Pacific Climate Update Coral Bleaching Heat Stress Analysis and Seasonal Guidance through August 2018 (Released May 7, 2018) Current conditions: NOAA Coral Reef Watch’s (CRW) near-real-time satellite monitoring shows mildly above- average sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in much of the western tropical Pacific Ocean, especially surrounding the eastern Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) and the Marshall Islands (Figure 1). Below-average SSTs are predominantly in the central equatorial Pacific Ocean around the Phoenix Islands, Kiribati, reaching eastward to the Marquesas Islands. In the northern Pacific Ocean around the Hawaiian Archipelago, above-average SSTs are currently influencing the southern Main Hawaiian Islands, while bands of spatially alternating above- and below-average SSTs are affecting the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands along its axis (Figure 1). During March 2018, the La Niña weakened but was still reflected by below-average SST across the east-central and east equatorial Pacific. The NOAA National Centers for Environmental Prediction’s El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) Alert System, currently at a La Niña Advisory, predicts conditions to return to ENSO-neutral during April-May and continue through Northern Hemisphere summer 2018. Figure 1. NOAA Coral Reef Watch's Satellite Sea Surface Temperature Anomaly product for the Pacific region. In recent months, HotSpots rarely surpassed 1˚C in most of the Pacific Ocean, with the exception of Clipperton Island, France (Figure 2); as a result, the current bleaching status for much of the Pacific remains at a Bleaching Watch or No Stress (Figure 3). Figure 2. NOAA Coral Reef Watch's Satellite Coral Bleaching HotSpot product for the Pacific region.