The Birds of Clipperton Island, Eastern Pacific

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country of Citizenship Active Exchange Visitors in 2017

Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 Active Exchange Visitors Country of Citizenship in 2017 AFGHANISTAN 418 ALBANIA 460 ALGERIA 316 ANDORRA 16 ANGOLA 70 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 29 ARGENTINA 8,428 ARMENIA 325 ARUBA 1 ASHMORE AND CARTIER ISLANDS 1 AUSTRALIA 7,133 AUSTRIA 3,278 AZERBAIJAN 434 BAHAMAS, THE 87 BAHRAIN 135 BANGLADESH 514 BARBADOS 58 BASSAS DA INDIA 1 BELARUS 776 BELGIUM 1,938 BELIZE 55 BENIN 61 BERMUDA 14 BHUTAN 63 BOLIVIA 535 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 728 BOTSWANA 158 BRAZIL 19,231 BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS 3 BRUNEI 44 BULGARIA 4,996 BURKINA FASO 79 BURMA 348 BURUNDI 32 CAMBODIA 258 CAMEROON 263 CANADA 9,638 CAPE VERDE 16 CAYMAN ISLANDS 1 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 27 CHAD 32 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 CHILE 3,284 CHINA 70,240 CHRISTMAS ISLAND 2 CLIPPERTON ISLAND 1 COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS 3 COLOMBIA 9,749 COMOROS 7 CONGO (BRAZZAVILLE) 37 CONGO (KINSHASA) 95 COSTA RICA 1,424 COTE D'IVOIRE 142 CROATIA 1,119 CUBA 140 CYPRUS 175 CZECH REPUBLIC 4,048 DENMARK 3,707 DJIBOUTI 28 DOMINICA 23 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 4,170 ECUADOR 2,803 EGYPT 2,593 EL SALVADOR 463 EQUATORIAL GUINEA 9 ERITREA 10 ESTONIA 601 ETHIOPIA 395 FIJI 88 FINLAND 1,814 FRANCE 21,242 FRENCH GUIANA 1 FRENCH POLYNESIA 25 GABON 19 GAMBIA, THE 32 GAZA STRIP 104 GEORGIA 555 GERMANY 32,636 GHANA 686 GIBRALTAR 25 GREECE 1,295 GREENLAND 1 GRENADA 60 GUATEMALA 361 GUINEA 40 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 GUINEA‐BISSAU -

Teacher's Guide

The World Map / Selected Features of Political Geography Map No. 64 ISBN: 978-2-89157-186-9 PRODUCT NO.: 400 9288 Washable: We strongly recommend the use of Crayola water-soluble markers. Bands and hooks 122 cm × 94 cm / 48 in × 37 in Other markers may damage your maps. 120° 90° 60° T 9090° ° E S Bellingshausen E A 150° S Canada and the World W Sea SOUTH ANTARCTIC I A N F E D E R T ARCTIC SHETLAND ISLANDS S S A T I O R U N Amundsen AT Yenisei ALEXANDER L a 120° A N n Sea N e ISLAND T 30° L IC The Base Map L e n O a Tiksi C THURSTON E A ISLAND N 70° Khatanga N e n l Salekhard Weddell rc ia i 60° C rth L id c swo and Sea r ti Ob Ell e c Map No. 64 A r Laptev Ronne n im 180° N A t ta n A an Ice Shelf r E ri Sea c A e t C ib THE WORLD ic A • S Contours and outlines are O l C N a NEW SIBERIAN ISLANDS BERKNER i Pevek t a Kara 70° r C e c T I n p A e S [RUSSIAN FEDERATION] a l F ri Sea ISLAND e R I C O r C C selected features of political geography 150° la T 80° A scale: 1 / 40 000 000 scale: 1 / 40 000 000 o I P P Coats Land C WRANGEL 0° Be N O ring Str ISLAND N 0 1 000 km 0 1 000 km carefully stylized to capture ait O V C A A Y A M L Y 80 [RUSSIAN FEDERATION] Z E 90° 100° 110 ° 120° 130° 140° 150° 160° 170° 180° 170° 160° 150° 140° 130° 120° 110 ° 100° 90° 80° 70° 60° 50° 40° 30° 20° 10° 0° 10° 20° 30° 40° 50° 60° 70° 80° ° E Arkhangelsk Queen Maud A Land N ARCTIC OCEAN Chukchi Barents N Ross Amundsen-Scott azimuthal equidistant projection azimuthal equidistant projection A Sea Sea 80 E Sea [U.S.A.] ° C ALASKA 70° 80° O the essentials. -

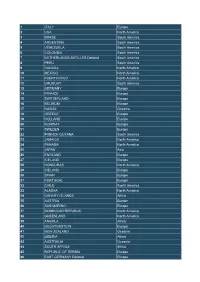

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania Prepared for the US Department of Defense’s Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance May 2020 Written by: Jonah Bhide Grace Frazor Charlotte Gorman Claire Huitt Christopher Zimmer Under the supervision of Dr. Joshua Busby 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 United States 8 Oceania 22 China 30 Australia 41 New Zealand 48 France 53 Japan 61 Policy Recommendations for US Government 66 3 Executive Summary Research Question The current strategic landscape in Oceania comprises a variety of complex and cross-cutting themes. The most salient of which is climate change and its impact on multilateral political networks, the security and resilience of governments, sustainable development, and geopolitical competition. These challenges pose both opportunities and threats to each regionally-invested government, including the United States — a power present in the region since the Second World War. This report sets out to answer the following questions: what are the current state of international affairs, complexities, risks, and potential opportunities regarding climate security issues and geostrategic competition in Oceania? And, what policy recommendations and approaches should the US government explore to improve its regional standing and secure its national interests? The report serves as a primer to explain and analyze the region’s state of affairs, and to discuss possible ways forward for the US government. Given that we conducted research from August 2019 through May 2020, the global health crisis caused by the novel coronavirus added additional challenges like cancelling fieldwork travel. However, the pandemic has factored into some of the analysis in this report to offer a first look at what new opportunities and perils the United States will face in this space. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

GENERAL AGREEMENT on ^ TARIFFS and TRADE *> *****1958

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON ^ TARIFFS AND TRADE *> *****1958 Limited Distribution APPLICATION OF THE GENERAL AGREEMENT Territories to which the Agreement is applied Annexed hereto is a list of the contracting parties and of the territories (according to information available to the secretariat) in respect of which the application of the Agreement has been made effective. This list is a revision of that which appeared in document G/5 under date of 17 March 1952. If there are any inaccuracies in this list, the contracting parties concerned are requested to notify the Executive Secretary not later than 1 October 1958 so that a revised list can be issued, if necessary, before the opening of the Thirteenth Session* L/843 Paee 2 Contracting parties to GATT and territories In respeot ot which the application of the Agreement has been made affective AUSTRALIA (Including Tasmania) AUSTRIA BELGIUM BELGIAN CONGO RUANDA-URUNDI (Trust Territory) BRAZIL (Including islands: Fernando de Noronha (including Rocks of Sao Pedro, Sao Paolo, Atoll das Rocas) Trinidad and Martim Vas) BURMA CANADA CEYLON CHILE (Including the islands of: Juan Fernandez group, Easter Islands, Sala y Gomez, San Feliz, San Ambrosio and western part of Tierra del Fuego) CUBA (Including Isle of Pines and some smaller islands) CZECHOSLOVAKIA DENMARK (Including Greenland and the Island of Disko, Faroe Islands, Islands of Zeeland, Funen, Holland, Falster, Bornholm and some 1700 small islands) DOMINICAN REPUBLIC (Including islands: Saona, Catalina, Beata and some smaller ones) FINLAND FRANCE (Including Corsica and Islands off the French Coast, the Saar and the principality of Monaco)! ALGERIA CAMEROONS (Trust Territory) FRENCH EQUATORIAL AFRICA FRENCH GUIANA (Including islands of St. -

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index A (General) Abeokuta: the Alake of Abram, Morris B.: see A (General) Abruzzi: Duke of Absher, Franklin Roosevelt: see A (General) Adams, C.E.: see A (General) Adams, Charles, Dr. D.F., C.E., Laura Franklin Delano, Gladys, Dorothy Adams, Fred: see A (General) Adams, Frederick B. and Mrs. (Eilen W. Delano) Adams, Frederick B., Jr. Adams, William Adult Education Program Advertisements, Sears: see A (General) Advertising: Exhibits re: bill (1944) against false advertising Advertising: Seagram Distilleries Corporation Agresta, Fred Jr.: see A (General) Agriculture Agriculture: Cotton Production: Mexican Cotton Pickers Agriculture: Department of (photos by) Agriculture: Department of: Weather Bureau Agriculture: Dutchess County Agriculture: Farm Training Program Agriculture: Guayule Cultivation Agriculture: Holmes Foundry Company- Farm Plan, 1933 Agriculture: Land Sale Agriculture: Pig Slaughter Agriculture: Soil Conservation Agriculture: Surplus Commodities (Consumers' Guide) Aircraft (2) Aircraft, 1907- 1914 (2) Aircraft: Presidential Aircraft: World War II: see World War II: Aircraft Airmail Akihito, Crown Prince of Japan: Visit to Hyde Park, NY Akin, David Akiyama, Kunia: see A (General) Alabama Alaska Alaska, Matanuska Valley Albemarle Island Albert, Medora: see A (General) Albright, Catherine Isabelle: see A (General) Albright, Edward (Minister to Finland) Albright, Ethel Marie: see A (General) Albright, Joe Emma: see A (General) Alcantara, Heitormelo: see A (General) Alderson, Wrae: see A (General) Aldine, Charles: see A (General) Aldrich, Richard and Mrs. Margaret Chanler Alexander (son of Charles and Belva Alexander): see A (General) Alexander, John H. Alexitch, Vladimir Joseph Alford, Bradford: see A (General) Allen, Mrs. Idella: see A (General) 2 Allen, Mrs. Mary E.: see A (General) Allen, R.C. -

Parasites of the Neotropic Cormorant Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) Brasilianus (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae) in Chile

Original Article ISSN 1984-2961 (Electronic) www.cbpv.org.br/rbpv Parasites of the Neotropic cormorant Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) brasilianus (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae) in Chile Parasitos da biguá Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) brasilianus (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae) do Chile Daniel González-Acuña1* ; Sebastián Llanos-Soto1,2; Pablo Oyarzún-Ruiz1 ; John Mike Kinsella3; Carlos Barrientos4; Richard Thomas1; Armando Cicchino5; Lucila Moreno6 1 Laboratorio de Parásitos y Enfermedades de Fauna Silvestre, Departamento de Ciencia Animal, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad de Concepción, Chillán, Chile 2 Laboratorio de Vida Silvestre, Departamento de Ciencia Animal, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad de Concepción, Chillán, Chile 3 Helm West Lab, Missoula, MT, USA 4 Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad Santo Tomás, Concepción, Chile 5 Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Mar del Plata, Argentina 6 Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas, Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile How to cite: González-Acuña D, Llanos-Soto S, Oyarzún-Ruiz P, Kinsella JM, Barrientos C, Thomas R, et al. Parasites of the Neotropic cormorant Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) brasilianus (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae) in Chile. Braz J Vet Parasitol 2020; 29(3): e003920. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612020049 Abstract The Neotropic cormorant Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) brasilianus (Suliformes: Phalacrocoracidae) is widely distributed in Central and South America. In Chile, information about parasites for this species is limited to helminths and nematodes, and little is known about other parasite groups. This study documents the parasitic fauna present in 80 Neotropic cormorants’ carcasses collected from 2001 to 2008 in Antofagasta, Biobío, and Ñuble regions. Birds were externally inspected for ectoparasites and necropsies were performed to examine digestive and respiratory organs in search of endoparasites. -

A New Breeding Colony of Blue-Footed Booby Sula Nebouxii at Islote González, Archipelago Islas Desventuradas, Chile

Marín & González: A new Blue-footed Booby breeding colony in Chile 189 A NEW BREEDING COLONY OF BLUE-FOOTED BOOBY SULA NEBOUXII AT ISLOTE GONZÁLEZ, ARCHIPELAGO ISLAS DESVENTURADAS, CHILE MANUEL MARÍN1,2 & RODRIGO GONZÁLEZ3 1Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Section of Ornithology, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007, USA 2Current address: Casilla 15, Melipilla, Chile ([email protected]) 3Santa María 7178, Vitacura, Santiago, Chile Received 13 January 2021, accepted 02 February 2021 ABSTRACT MARÍN, M. & GONZÁLEZ, R. 2021. A new breeding colony of Blue-footed Booby Sula nebouxii at Islote González, Archipelago Islas Desventuradas, Chile. Marine Ornithology 49: 189–192. We describe a new disjunct population of Blue-footed Booby Sula nebouxii at Islote González in the Islas Desventuradas archipelago. Though likely much larger, the population size at the time of our survey was a minimum of 16 breeding pairs. On 14–15 December 2020, two pairs of boobies with nestlings and four pairs with empty nests were found. Likely the species is a recent arrival to the archipelago, perhaps during one of the strong El Niño events between 1970 and 2001 (especially 1982/83, when the species was first recorded in Chile). Blue-footed Booby might also nest on different areas at San Félix Island and some smaller islets around the archipelago, where they would have no nesting-site competition from the larger Masked Booby S. dactylatra. Key words: Blue-footed Booby, Sula nebouxii, breeding, Islas Desventuradas, Chile INTRODUCTION northern coast between 21°54′S and 23°05′S (Guerra 1983). Guerra observed 10 individuals in a 132-km transect while surveying for Within the Sulidae, a widespread and prolific group of piscivorous guano birds and fur seals along the coast. -

Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No

BIRD CHECKLIST Leaders: Steve Ogle Eagle-Eye Tours 2018 Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No. Common Name Latin Name Heard RHEIFORMES: Rheidae 1 Lesser Rhea Rhea pennata s TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 2 Elegant Crested-Tinamou Eudromia elegans s ANSERIFORMES: Anhimidae 3 Southern Screamer Chauna torquata s ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 4 White-faced Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna viduata s 5 Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor s 6 Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus s 7 Coscoroba Swan Coscoroba coscoroba s 8 Upland Goose Chloephaga picta s 9 Kelp Goose Chloephaga hybrida s 10 Flying Steamer-Duck Tachyeres patachonicus s 11 Flightless Steamer-Duck Tachyeres pteneres s 12 White-headed Steamer-Duck Tachyeres leucocephalus s 13 Crested Duck Lophonetta specularioides s 14 Spectacled Duck Speculanas specularis s 15 Brazilian Teal Amazonetta brasiliensis s 16 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata s 17 Chiloe Wigeon Anas sibilatrix s 18 Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera s 19 Red Shoveler Anas platalea s 20 Yellow-billed Pintail Anas georgica s 21 Silver Teal Anas versicolor s 22 Yellow-billed Teal Anas flavirostris s 23 Rosy-billed Pochard Netta peposaca s 24 Black-headed Duck Heteronetta atricapilla s 25 Lake Duck Oxyura vittata s PODICIPEDIFORMES: Podicipedidae 26 White-tufted Grebe Rollandia rolland s 27 Great Grebe Podiceps major s 28 Silvery Grebe Podiceps occipitalis s PHOENICOPTERIFORMES: Phoenicopteridae 29 Chilean Flamingo Phoenicopterus chilensis s SPHENISCIFORMES: Spheniscidae 30 King Penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus s 31 Gentoo Penguin Pygoscelis papua s 32 Magellanic Penguin Spheniscus magellanicus s PROCELLARIIFORMES: Diomedeidae 33 Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris s Page 1 of 6 BIRD CHECKLIST Leaders: Steve Ogle Eagle-Eye Tours 2018 Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No. -

Radiocarbon Ages of Lacustrine Deposits in Volcanic Sequences of the Lomas Coloradas Area, Socorro Island, Mexico

Radiocarbon Ages of Lacustrine Deposits in Volcanic Sequences of the Lomas Coloradas Area, Socorro Island, Mexico Item Type Article; text Authors Farmer, Jack D.; Farmer, Maria C.; Berger, Rainer Citation Farmer, J. D., Farmer, M. C., & Berger, R. (1993). Radiocarbon ages of lacustrine deposits in volcanic sequences of the Lomas Coloradas area, Socorro Island, Mexico. Radiocarbon, 35(2), 253-262. DOI 10.1017/S0033822200064924 Publisher Department of Geosciences, The University of Arizona Journal Radiocarbon Rights Copyright © by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona. All rights reserved. Download date 28/09/2021 10:52:25 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/653375 [RADIOCARBON, VOL. 35, No. 2, 1993, P. 253-262] RADIOCARBON AGES OF LACUSTRINE DEPOSITS IN VOLCANIC SEQUENCES OF THE LOMAS COLORADAS AREA, SOCORRO ISLAND, MEXICO JACK D. FARMERI, MARIA C. FARMER2 and RAINER BERGER3 ABSTRACT. Extensive eruptions of alkalic basalt from low-elevation fissures and vents on the southern flank of the dormant volcano, Cerro Evermann, accompanied the most recent phase of volcanic activity on Socorro Island, and created 14C the Lomas Coloradas, a broad, gently sloping terrain comprising the southern part of the island. We obtained ages of 4690 ± 270 BP (5000-5700 cal BP) and 5040 ± 460 BP (5300-6300 cal BP) from lacustrine deposits that occur within volcanic sequences of the lower Lomas Coloradas. Apparently, the sediments accumulated within a topographic depression between two scoria cones shortly after they formed. The lacustrine environment was destroyed when the cones were breached by headward erosion of adjacent stream drainages. -

Parque Nacional Revillagigedo

EVALUATION REPORT Parque Nacional Revillagigedo Location: Revillagigedo Archipelago, Mexico, Eastern Pacific Ocean Blue Park Status: Nominated (2020), Evaluated (2021) MPAtlas.org ID: 68808404 Manager(s): Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP) MAPS 2 1. ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA 1.1 Biodiversity Value 4 1.2 Implementation 8 2. AWARD STATUS CRITERIA 2.1 Regulations 11 2.2 Design, Management, and Compliance 13 3. SYSTEM PRIORITIES 3.1 Ecosystem Representation 18 3.2 Ecological Spatial Connectivity 18 SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION: Evidence of MPA Effects 19 Figure 1: Revillagigedo National Park, located 400 km south of Mexico’s Baja peninsula, covers 148,087 km2 and includes 3 zone types – Research (solid blue), Tourism (dotted), and Traditional Use/Naval (lined) – all of which ban all extractive activities. It is partially surrounded by the Deep Mexican Pacific Biosphere Reserve (grey) which protects the water column below 800 m. All 3 zones of the National Park are shown in the same shade of dark blue, reflecting that they all have Regulations Based Classification scores ≤ 3, corresponding with a fully protected status (see Section 2.1 for more information about the regulations associated with these zones). (Source: MPAtlas, Marine Conservation Institute) 2 Figure 2: Three-dimensional map of the Revillagigedo Marine National Park shows the bathymetry around Revillagigedo’s islands. (Source: Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, 2018) 3 1.1 Eligibility Criteria: Biodiversity Value (must satisfy at least one) 1.1.1. Includes rare, unique, or representative ecosystems. The Revillagigedo Archipelago is comprised of a variety of unique ecosystems, due in part to its proximity to the convergence of five tectonic plates.