The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRANS-PACIFIC PARTNERSHIP CORPORATIONS BEFORE PEOPLE and DEMOCRACY John A

ISSUE REPORT THE TRANS-PACIFIC PARTNERSHIP CORPORATIONS BEFORE PEOPLE AND DEMOCRACY john a. powell, Elsadig Elsheikh, and Hossein Ayazi HAASINSTITUTE.BERKELEY.EDU/TPP THIS REPORT IS PUBLISHED BY MAPS, GRAPHICS, DATA VISUALIZATION HAAS INSTITUTE FOR A FAIR AND INCLUSIVE SOCIETY Samir Gambhir AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY The Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society brings DESIGN/LAYOUT together researchers, community stakeholders, policymakers, Rachelle Galloway-Popotas and communicators to identify and challenge the barriers to an inclusive, just, and sustainable society in order to create EDITORS transformative change. The Institute serves as a national hub of Rachelle Galloway-Popotas researchers and community partners and takes a leadership role in Sara Grossman translating, communicating, and facilitating research, policy, and Stephen Menendian strategic engagement. The Haas Institute advances research and policy related to marginalized people while essentially touching all COPYEDITORS who benefit from a truly diverse, fair, and inclusive society. Sara Grossman Ebonye Gussine Wilkins AUTHORS THE WORK OF THE HAAS INSTITUTE IS GENEROUSLY SUPPORTED BY THE FOLLOWING: john a. powell is Director of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society and holds the Robert D. Haas Chancellor’s Chair in Equity and Inclusion at the Akonadi Foundation University of California, Berkeley, where he is also a Professor of Law, African The Annie E. Casey Foundation American, and Ethnic Studies. john previously directed the Kirwan Institute The California Endowment for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University and the Institute The Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund for Race and Poverty at the University of Minnesota. -

Country of Citizenship Active Exchange Visitors in 2017

Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 Active Exchange Visitors Country of Citizenship in 2017 AFGHANISTAN 418 ALBANIA 460 ALGERIA 316 ANDORRA 16 ANGOLA 70 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 29 ARGENTINA 8,428 ARMENIA 325 ARUBA 1 ASHMORE AND CARTIER ISLANDS 1 AUSTRALIA 7,133 AUSTRIA 3,278 AZERBAIJAN 434 BAHAMAS, THE 87 BAHRAIN 135 BANGLADESH 514 BARBADOS 58 BASSAS DA INDIA 1 BELARUS 776 BELGIUM 1,938 BELIZE 55 BENIN 61 BERMUDA 14 BHUTAN 63 BOLIVIA 535 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 728 BOTSWANA 158 BRAZIL 19,231 BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS 3 BRUNEI 44 BULGARIA 4,996 BURKINA FASO 79 BURMA 348 BURUNDI 32 CAMBODIA 258 CAMEROON 263 CANADA 9,638 CAPE VERDE 16 CAYMAN ISLANDS 1 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 27 CHAD 32 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 CHILE 3,284 CHINA 70,240 CHRISTMAS ISLAND 2 CLIPPERTON ISLAND 1 COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS 3 COLOMBIA 9,749 COMOROS 7 CONGO (BRAZZAVILLE) 37 CONGO (KINSHASA) 95 COSTA RICA 1,424 COTE D'IVOIRE 142 CROATIA 1,119 CUBA 140 CYPRUS 175 CZECH REPUBLIC 4,048 DENMARK 3,707 DJIBOUTI 28 DOMINICA 23 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 4,170 ECUADOR 2,803 EGYPT 2,593 EL SALVADOR 463 EQUATORIAL GUINEA 9 ERITREA 10 ESTONIA 601 ETHIOPIA 395 FIJI 88 FINLAND 1,814 FRANCE 21,242 FRENCH GUIANA 1 FRENCH POLYNESIA 25 GABON 19 GAMBIA, THE 32 GAZA STRIP 104 GEORGIA 555 GERMANY 32,636 GHANA 686 GIBRALTAR 25 GREECE 1,295 GREENLAND 1 GRENADA 60 GUATEMALA 361 GUINEA 40 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 GUINEA‐BISSAU -

Norfolk Island Nights with Breakfast Daily, Lagoon Cruise, Golf Green Fees, $3799 Kids Club & Kids Eat Free! SAVE $1165 Head South

HEaD SOUtH FInD NoRTH EXCLUSIVE SOUTH PACIFIC DEALS SALE ENDS 31 JANUARY! FIJI VANUATU COOK ISLANDS CRUSOE’S RETREAT BREAKAS BEACH RESORT (15+) CLUB RARO RESORT Return flights, transfers & Return flights, transfers & Return flights, transfers 4 nights with breakfast and 6 nights with breakfast daily, & 6 nights with intro dive $1199 afternoon tea daily, massage $899 massage, cocktails, cooking $1249 & NZ$50 credit! SAVE $1025 & cocktail! SAVE $975 class & Port Vila Tour! SAVE $1200 THE EDGEWATER RESORT AND SPA THE WARWICK FIJI RAMADA RESORT PORT VILA Return flights, transfers & 6 nights Return flights, transfers & 5 nights Return flights, transfers & 7 nights with breakfast daily, resort credit, $ dinner and show, massage $ with breakfast daily, FJ$200 1249 with breakfast daily, 2 massages, $1449 1499 Resort Credit & 2 spa treatments! SAVE $1060 Port Vila Tour & WiFi! SAVE $1910 & beverages! SAVE $1150 RADISSON BLU RESORT FIJI TAMANU ON THE BEACH MANUIA BEACH RESORT (16+) DENARAU ISLAND Return flights, transfers & 7 nights Return flights, transfers & 6 nights $ Return flights, transfers & 5 nights with breakfast daily, massage, with breakfast daily, resort credit, 1899 with breakfast daily, kids club $1299 $100 resort credit, welcome $1599 3 day scooter hire & a massage! SAVE $1110 & kids eat free! SAVE $1690 cocktail & WiFi! SAVE $770 RUMOURS LUXURY VILLAS & SPA (15+) THE NAVITI RESORT BOKISSA PRIVATE ISLAND RESORT Return flights, transfers & 6 nights with a private plunge pool, Return flights, transfers & 5 nights Return flights, transfers -

Enhancing Safety, Security and Sustainability of Apia Port: Due

Due Diligence Report Project Number: 47358-002 May 2019 SAM: Enhancing Safety, Security and Sustainability of Apia Port Project (Grant xxxx) Prepared by the Samoa Ports Authority for the Asian Development Bank. This due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgements as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Enhancing Safety, Security and Sustainability of Apia Port – Social and Poverty Assessment Report CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 4 April 2016) Tala – Samoan Tala (SAT) = $1.00 = ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank AUA - Apia Urban Area DDR - Due Diligence Report EA - Executing Agency EMP - Environmental Management Plan EPA - Environmental Protection Agency GOS - Government of the Samoa GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism HIES - Household Income and Expenditures Survey IA - Implementing Agency IP - Indigenous People IR - Involuntary Resettlement MNRE - Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment MOF - Ministry of Finance MOR - Ministry of Revenue PIC - Pacific Island Countries PUMA - Planning and Urban Management Authority RP - Resettlement Plan SPA - Samoa Ports Authority -

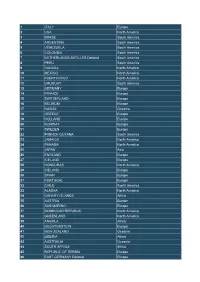

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

Regionalism, Security & Cooperation in Oceania

Regionalism, Security & Cooperation in Oceania Edited by Rouben Azizian and Carleton Cramer Regionalism, Security & Cooperation in Oceania Edited by Rouben Azizian and Carleton Cramer First published June 2015 Published by the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies 2058 Maluhia Road Honolulu, HI 96815 www.apcss.org For reprint permissions, contact the editors via: [email protected] ISBN 978-0-9719416-7-0 Printed in the United States of America. Vanuatu Harbor Photo used with permission ©GlennCraig Group photo by: Philippe Metois Maps used with permission from: Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) Center for Pacific Island Studies (CPIS) University of Hawai’i at Manoa This book is dedicated to the people of Vanuatu who are recovering from the devastating impact of Cyclone Pam, which struck the country on March 13, 2015. 2 Regionalism, Security & Cooperation in Oceania Table of Contents Acknowledgments and Disclaimers .............................................. 4 List of Abbreviations and Glossary ............................................... 6 Introduction: Regionalism, Security and Cooperation in Oceania Rouben Azizian .............................................................................. 9 Regional Security Architecture in the Pacific 1 Islands Region: Rummaging through the Blueprints R.A. Herr .......................................................................... 17 Regional Security Environment and Architecture in the Pacific Islands Region 2 Michael Powles ............................................................... -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Beyond Internal Conflict: the Emergent Practice of Climate Security

Journal of Peace Research 2021, Vol. 58(1) 186–194 Beyond internal conflict: The emergent ª The Author(s) 2020 Article reuse guidelines: practice of climate security sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/0022343320971019 journals.sagepub.com/home/jpr Joshua W Busby LBJ School of Public Affairs, University of Austin-Texas Abstract The field of climate and security has matured over the past 15 years, moving from the margins of academic research and policy discussion to become a more prominent concern for the international community. The practice of climate and security has a broad set of concerns extending beyond climate change and armed conflict. Different national governments, international organizations, and forums have sought to mainstream climate security concerns empha- sizing a variety of challenges, including the risks to military bases, existential risks to low-lying island countries, resource competition, humanitarian emergencies, shocks to food security, migration, transboundary water manage- ment, and the risks of unintended consequences from climate policies. Despite greater awareness of these risks, the field still lacks good insights about what to do with these concerns, particularly in ‘fragile’ states with low capacity and exclusive political institutions. Keywords climate change, climate security, environmental security, human security During a visit to the Pacific island nation of Tuvalu in security; and third, how policy can be made more effec- 2019, UN Secretary-General Anto´nio Guterres wrote on tive going forward. Twitter: ‘We must stop Tuvalu from sinking and the world from sinking with Tuvalu’ (United Nations, The challenges 2019). Guterres underscored the existential risks of cli- mate change for low-lying island countries. -

Toward a Constitutionalism of the Global South

1 1 CN Introduction CT Toward a Constitutionalism of the Global South Daniel Bonilla The grammar of modern constitutionalism determines the structure and limits of key components of contemporary legal and political discourse. This grammar constitutes an important part of our legal and political imagination. It determines what questions we ask about our polities, as well as the range of possible answers to these questions. This grammar consists of a series of rules and principles about the appropriate use of concepts like people, self-government, citizen, rights, equality, autonomy, nation, and popular sovereignty.1 Queries about the normative relationship among state, nation, and cultural diversity; the criteria that should be used to determine the legitimacy of the state; the individuals who can be considered members of the polity; the distinctions and limits between the private and public spheres; and the differences between autonomous and heteronomous political communities makes sense to us because they emerge from the rules and principles of modern constitutionalism. Responses to these questions are certainly diverse. Different traditions of interpretation in modern constitutionalism – liberalism, communitarianism, and nationalism, among others – compete to control the way these concepts are understood and put into practice.2 Yet these questions and answers cannot violate the conceptual borders established by modern constitutionalism. If they do, they would be considered unintelligible, irrelevant, or useless. Today, for example, it would be difficult to accept the relevancy of a question about the relationship between the 2 2 legitimacy of the state and the divine character of the king. It would also be very difficult to consider valuable the idea that the fundamental rights of citizens should be a function of race or gender. -

Perspectives on a Pacific Partnership

The United States and New Zealand: Perspectives on a Pacific Partnership Prepared by Bruce Robert Vaughn, PhD With funding from the sponsors of the Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy August 2012 Established by the Level 8, 120 Featherston Street Telephone +64 4 472 2065 New Zealand government in 1995 PO Box 3465 Facsimile +64 4 499 5364 to facilitate public policy dialogue Wellington 6140 E-mail [email protected] between New Zealand and New Zealand www.fulbright.org.nz the United States of America © Bruce Robert Vaughn 2012 Published by Fulbright New Zealand, August 2012 The opinions and views expressed in this paper are the personal views of the author and do not represent in whole or part the opinions of Fulbright New Zealand or any New Zealand government agency. Nor do they represent the views of the Congressional Research Service or any US government agency. ISBN 978-1-877502-38-5 (print) ISBN 978-1-877502-39-2 (PDF) Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy Established by the New Zealand Government in 1995 to reinforce links between New Zealand and the US, Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy provide the opportunity for outstanding mid-career professionals from the United States of America to gain firsthand knowledge of public policy in New Zealand, including economic, social and political reforms and management of the government sector. The Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy were named in honour of Sir Ian Axford, an eminent New Zealand astrophysicist and space scientist who served as patron of the fellowship programme until his death in March 2010. -

The UN Security Council and Climate Change

Research Report The UN Security Council and Climate Change Dead trees form an eerie tableau Introduction on the shores of Maubara Lake in Timor-Leste. UN Photo/Martine Perret At the outset of the Security Council’s 23 Feb- particular the major carbon-emitting states, will ruary 2021 open debate on climate and security, show the level of commitment needed to reduce world-renowned naturalist David Attenborough carbon emissions enough to stave off the more dire delivered a video message urging global coopera- predictions of climate modellers. tion to tackle the climate crisis. “If we continue on While climate mitigation and adaptation 2021, No. #2 21 June 2021 our current path, we will face the collapse of every- measures are within the purview of the UN thing that gives us our security—food production; Framework Convention on Climate Change This report is available online at securitycouncilreport.org. access to fresh water; habitable, ambient tempera- (UNFCCC) and contributions to such measures tures; and ocean food chains”, he said. Later, he are outlined in the Paris Agreement, many Secu- For daily insights by SCR on evolving Security Council actions please added, “Please make no mistake. Climate change rity Council members view climate change as a subscribe to our “What’s In Blue” series at securitycouncilreport.org is the biggest threat to security that humans have security threat worthy of the Council’s attention. or follow @SCRtweets on Twitter. ever faced.” Such warnings have become common. Other members do not. One of the difficulties in And while the magnitude of this challenge is widely considering whether or not the Council should accepted, it is not clear if the global community, in play a role (and a theme of this report) is that Security Council Report Research Report June 2021 securitycouncilreport.org 1 1 Introduction Introduction 2 The Climate-Security Conundrum 4 The UN Charter and Security there are different interpretations of what is on Climate and Security, among other initia- Council Practice appropriate for the Security Council to do tives. -

'Missionaries' in Bangladesh

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Exploring the mission-development nexus through stories from Christian ‘missionaries’ in Bangladesh Anna Thompson 2012 A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Development Studies School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences Victoria University of Wellington Abstract Over the past decade, development research and policy has increasingly paid attention to religion and belief. Donors and researchers have progressively engaged with faith-based organisations and recipients. However, Christian mission and ‗missionaries‘ remain underexplored aspects within religion and development discourses. In response, this research explores stories from eleven Christian ‗missionaries‘ in Bangladesh. Firstly, I assess how the changing non-governmental sector in Bangladesh influenced participants‘ activities. Secondly, I contextualise their stories within religion and development discourses with reference to analyses of development workers. Finally, I reflect on the significance of spirituality in participants‘ lives. I also describe how spirituality played a role in my research. I frame this research within feminist and poststructuralist ways of knowing. Methodologically, I conducted semi-structured interviews and ‗hung out‘ with participants. I ‗wrote myself-in‘ to this research to highlight how the process intersected with my own subject positions. I found that participants‘ engaged with development in similar ways to development workers as analysed by others. They reproduced discourses of modernisation, expertise, altruism, and the ‗third world‘. They additionally responded to Christian discourses, such as ‗calling‘. Participants‘ activities and subjectivities were shaped by these intersecting discourses, and were also shaped by the historic and current setting of Bangladesh.