Notes, Chiefly Distributional, on Some Florida Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Baraminological Analysis of the Land Fowl (Class Aves, Order Galliformes)

Galliform Baraminology 1 Running Head: GALLIFORM BARAMINOLOGY A Baraminological Analysis of the Land Fowl (Class Aves, Order Galliformes) Michelle McConnachie A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2007 Galliform Baraminology 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Timothy R. Brophy, Ph.D. Chairman of Thesis ______________________________ Marcus R. Ross, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Harvey D. Hartman, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Judy R. Sandlin, Ph.D. Assistant Honors Program Director ______________________________ Date Galliform Baraminology 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, without Whom I would not have had the opportunity of being at this institution or producing this thesis. I would also like to thank my entire committee including Dr. Timothy Brophy, Dr. Marcus Ross, Dr. Harvey Hartman, and Dr. Judy Sandlin. I would especially like to thank Dr. Brophy who patiently guided me through the entire research and writing process and put in many hours working with me on this thesis. Finally, I would like to thank my family for their interest in this project and Robby Mullis for his constant encouragement. Galliform Baraminology 4 Abstract This study investigates the number of galliform bird holobaramins. Criteria used to determine the members of any given holobaramin included a biblical word analysis, statistical baraminology, and hybridization. The biblical search yielded limited biosystematic information; however, since it is a necessary and useful part of baraminology research it is both included and discussed. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

On the Origin and Evolution of Nest Building by Passerine Birds’

T H E C 0 N D 0 R r : : ,‘ “; i‘ . .. \ :i A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY ,I : Volume 99 Number 2 ’ I _ pg$$ij ,- The Condor 99~253-270 D The Cooper Ornithological Society 1997 ON THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF NEST BUILDING BY PASSERINE BIRDS’ NICHOLAS E. COLLIAS Departmentof Biology, Universityof California, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1606 Abstract. The object of this review is to relate nest-buildingbehavior to the origin and early evolution of passerinebirds (Order Passeriformes).I present evidence for the hypoth- esis that the combinationof small body size and the ability to place a constructednest where the bird chooses,helped make possiblea vast amountof adaptiveradiation. A great diversity of potential habitats especially accessibleto small birds was created in the late Tertiary by global climatic changes and by the continuing great evolutionary expansion of flowering plants and insects.Cavity or hole nests(in ground or tree), open-cupnests (outside of holes), and domed nests (with a constructedroof) were all present very early in evolution of the Passeriformes,as indicated by the presenceof all three of these basic nest types among the most primitive families of living passerinebirds. Secondary specializationsof these basic nest types are illustratedin the largest and most successfulfamilies of suboscinebirds. Nest site and nest form and structureoften help characterizethe genus, as is exemplified in the suboscinesby the ovenbirds(Furnariidae), a large family that builds among the most diverse nests of any family of birds. The domed nest is much more common among passerinesthan in non-passerines,and it is especially frequent among the very smallestpasserine birds the world over. -

SAN JACINTO WILDLIFE AREA BIRD LIST (Including Lake Perris State Recreation Area) by D

SAN JACINTO WILDLIFE AREA BIRD LIST (including Lake Perris State Recreation Area) by D. M. Morton, Updated February 2008 The following list includes 319 species that have been reported from the combined San Jacinto Wildlife Area and Lake Perris State Recreation Area. Two species, Black Rail, Curlew Sandpiper (queried?) have not been verified and one, Golden Plover sp., was only identified at the genus level. The list includes a few old records predating the establishment of the San Jacinto Wildlife Area and Lake Perris Recreation Area that are presumed to have been in or adjacent to this area. The checklist follows the taxonomy of the American Ornithogists’ Union (AOU) 1997 7th edition checklist and subsequent supplements. The area covered by this list includes a wide variety of habitats ranging from open water at Lake Perris to dry coastal sage. Observational frequency is based on a full day of birding that includes the proper habitat for individual species. ‘Common’ indicates one or more individuals should be seen any day birding. ‘Uncommon’ indicates should be seen 25-50 % of days birding. ‘Rare’ indicates infrequently to very infrequently seen species. ‘Accidental’ refers to one to a few occurrences of a species and very unlikely to be seen. The occurrence and frequency of water and shore birds is partly governed by ephemeral Mystic Lake that fills a shallow closed depression in the San Jacinto Fault Zone. When the closed depression floods to form Mystic Lake a large number of transient and wintering birds are attracted, providing excellent opportunities to study shore birds. Mystic Lake is the site of a number of accidental and rare recorded species in the area. -

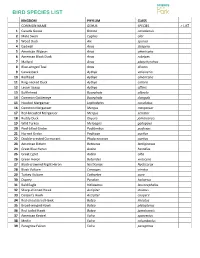

Bird Species List

SCIENCE in the BIRD SPECIES LIST KINGDOM PHYLUM CLASS COMMON NAME GENUS SPECIES ✓ LIST 1 Canada Goose Branta canadensis 2 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 3 Wood Duck Aix sponsa 4 Gadwall Anas strepera 5 American Wigeon Anas americana 6 American Black Duck Anas rubripes 7 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos 8 Blue-winged Teal Anas discors 9 Canvasback Aythya valisineria 10 Redhead Aythya americana 11 Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris 12 Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis 13 Bufflehead Bucephala albeola 14 Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula 15 Hooded Merganser Lophodytes cucullatus 16 Common Merganser Mergus merganser 17 Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator 18 Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 19 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 20 Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps 21 Horned Grebe Podiceps auritus 22 Double-crested Cormorant Phalacrocorax auritus 23 American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus 24 Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias 25 Great Egret Ardea alba 26 Green Heron Butorides virescens 27 Black-crowned Night Heron Nycticorax Nycticorax 28 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus 29 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 30 Osprey Pandion haliaetus 31 Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus 32 Sharp-shinned Hawk Accipiter striatus 33 Cooper's Hawk Accipiter cooperii 34 Red-shouldered Hawk Buteo lineatus 35 Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus 36 Red-tailed Hawk Buteo jamaicensis 37 American Kestrel Falco sparverius 38 Merlin Falco columbarius 39 Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus SCIENCE in the BIRD SPECIES LIST 40 American Coot Fulica americana 41 COMMON NAME GENUS SPECIES ✓ LIST 42 Killdeer -

Aves (Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae (Chachalacas, Guans & Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds, Cormorants & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed Hawk Buteo jamaicensis Roadside Hawk Rupornis magnirostris Short-tailed Hawk Buteo brachyurus Swainson's Hawk Buteo swainsoni Swallow-tailed -

Taxonomy and Biogeography of New World Quail

National Quail Symposium Proceedings Volume 3 Article 2 1993 Taxonomy and Biogeography of New World Quail R. J. Gutierrez Humboldt State University Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/nqsp Recommended Citation Gutierrez, R. J. (1993) "Taxonomy and Biogeography of New World Quail," National Quail Symposium Proceedings: Vol. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/nqsp/vol3/iss1/2 This General is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in National Quail Symposium Proceedings by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/nqsp. Gutierrez: Taxonomy and Biogeography of New World Quail TAXONOMYAND BIOGEOGRAPHYOFNEW WORLD QUAIL R. J. GUTIERREZ,Department of Wildlife, Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA 95521 Abstract: New World quail are a distinct genetic lineage within the avian order Galliformes. The most recent taxonomic treatment classifies the group as a separate family, Odontophoridae, within the order. Approximately 31 species and 128-145 subspecies are recognized from North and South America. Considerable geographic variation occurs within some species which leads to ambiguity when describing species limits. A thorough analysis of the Galliformes is needed to clarify the phylogenetic relationships of these quail. It is apparent that geologic or climatic isolating events led to speciation within New World quail. Their current distribution suggests that dispersal followed speciation. Because the genetic variation found in this group may reflect local adaption, the effect of translocation and stocking of pen-reared quail on local population genetic structure must be critically examined. -

A Taxonomic List of the Major Groups of Birds -With Indications of North American Families

A Taxonomic List of the Major Groups of Birds -with indications of North American families By David Lahti 2/2016 Following are the major groups of birds, as they have been designated so far, focusing especially on the Orders and Families of the current birds of the world, and designating (with underlines) families represented in North and Violet sabrewing Campylopterus Middle America. hemileucurus (Apodiformes: Trochilidae). Monteverde, Costa Rica (April Lahti, 2008). Avialans and extinct birds: A brief nested lineage is presented initially that starts with the Avialans—those dinosaurs believed to be more closely related to birds than to other dinos such as Deinonychus. Extinct fossil bird groups are presented mostly according to Chiappe (2001, 2002) and Sereno (2005). Until we get to modern birds (Neornithes), I have not represented groups as orders or families, because the most reliable paleontological data is still presented largely only at the level of genus. Some researchers (and researchers from some cultures in particlular) are apt to ascribe order status to their fossil finds, but it is very possible that nearly every genus discovered in the Jurassic and Cretaceous, at least, merits order status. Therefore I have avoided dividing genera into families and orders, and mentioned only the number of genera that have been described. Among modern birds, Neornithes, the vast majority of fossil and subfossil finds are thought to be consistent with contemporary orders; thus only four extinct orders are listed here, each designated by a dagger (†). Two of them (Lithornithiformes and Gastornithiformes) went extinct before the historical period, so are listed in the introductory ancient lineage; the other two (Dinornithiformes and Aepyornithiformes) went extinct in the historical period (because of humans), and so are in the main list. -

DOMESTIC SPECIES LIST August 2010 Animal Group Order Family Genus Species Common Name(S) Comments

Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department page 1 of 3 Wild Bird and Animal Importation and Possession DOMESTIC SPECIES LIST August 2010 Animal Group Order Family Genus Species Common Name(s) Comments Mammals* Artiodactyla Bovidae Bison bison American bison Mammals Artiodactyla Bovidae Bos indicus Zebu Mammals Artiodactyla Bovidae Bos grunniens Domestic yak Mammals Artiodactyla Bovidae Bos taurus Domestic cow Mammals Artiodactyla Bovidae Bubalis bubalis Domestic water buffalo Including breeds and varrieties derived from the wild Mammals Artiodactyla Bovidae Capra hircus Domestic goat goat or bezoar (Capra aegagrus ). Mammals Artiodactyla Bovidae Ovis aries Domestic sheep Mammals Artiodactyla Camelidae Camelus dromedarius Dromedary Mammals Artiodactyla Camelidae Lama glama Llama Mammals Artiodactyla Camelidae Lama pacos Alpaca Mammals Artiodactyla Cervidae Cervus elaphus European Red Deer Mammals Artiodactyla Cervidae Dama dama Fallow deer Including breeds and varieties derived from the wild boar (Sus scrofa ) but not including free-living or feral Mammals Artiodactyla Suidae Sus domesticus Domestic swine wild boars or wild swine. Mammals Carnivora Canidae Canis familiaris Domestic dog Mammals Carnivora Felidae Felis catus Domestic cat Mammals Carnivora Mustelidae Mustela putorious furo European ferret Including breeds, varieties, and strains derived from the European rabbit but not including the Eurpoean rabbit ferae naturae and not including the so-called Mammals Lagomorpha Leporidae Oryctolagus cuniculus Domestic rabbit "San Juan" rabbit. Mammals Perissodactyla Equidae Equus asinus Domestic ass Mammals Perissodactyla Equidae Equus caballus Domestic horse Birds* Anseriformes Anatidae Alopochen aegyptiaca Domestic goose Derived from the Egyptian goose Derived from the Mallard (Anas platyrhinos ), including, but not restricted to, Aylesbury duck, Blue Swedish duck, Buff duck, Cayuga duck, Crested White duck, English call duck, Indian runner duck, Pekin duck, and Birds Anseriformes Anatidae Anas platyrhynchos Domestic duck Roen duck. -

Neotropical Birds

HH 12 Neotropical Birds IRDSare a magnet that helps draw visitors to the Neotropics. Some come merely to augment an already long life list of species, wanting to see Bmore parrots, more tanagers, more hummingbirds, some toucans, and hoping for a chance encounter with the ever-elusive harpy eagle. Others, fol- lowing in the footsteps of Darwin, Wallace, and their kindred, investigate birds in the hopes of adding knowledge about the mysteries of ecology and evo- lution in this the richest of ecosystems. Opportunities abound for research topics. There are many areas of Neotropical ornithology that are poorly stud- ied, hardly a surprise given the abundance of potential research subjects. Like all other areas of tropical research, however, bird study is negatively affected by increasingly high rates of habitat loss. This chapter is an attempt to convey the uniqueness and diversity of a Neotropical avifauna whose richness faces a somewhat uncertain future. Avian diversity is very high in the Neotropics. The most recent species count totals 3,751 species representing 90 families, 28 of which are endemic to the Neotropics, making this biogeographic realm the most species-rich on Earth (Stotz et al. 1996). But seeing all 3,751 species will present a bit of a challenge. When Henry Walter Bates (1892) was exploring Amazonia, he was moved to comment on the difficulty of seeing Neotropical birds in dense rainforest: The first thing that would strike a new-comer in the forests of the Upper Amazons would be the general scarcity of birds: indeed, it often happened that I did not meet with a single bird during a whole day’s ramble in the richest and most varied parts of the woods. -

Proposed New CITES Standard References for Nomenclature of Birds (Class Aves) Report of the Consultant November 14, 2018

CoP18 Doc. xx Annex 5 Proposed New CITES Standard References for Nomenclature of Birds (Class Aves) Report of the Consultant November 14, 2018 Ronald Orenstein Mississauga, Ontario, Canada L5L3W2 [email protected] Introduction Avian taxonomy has undergone a sea change since the publication of the 3rd edition of the Howard and Moore checklist of the birds of the world (Dickinson, 2003; hereafter H&M3). As the editors point out in the introduction (p. xi) to Volume 1 of the 4th edition of that checklist (Dickinson and Christidis (eds), 2013 (v. 1, Non-Passerines), 2014 (v. 2, Passerines); hereafter H&M4): “The explosion of research on the phylogeny of birds in the last decade, more than in any other in history, has led to dramatic changes in our understanding of the relationships among birds. This revolution means that the classification in H&M3 is not just badly out of date but in many places virtually obsolete. From relationships among orders of birds, to composition of families and genera, to many revelations of hidden species diversity, the classification of birds of the world has undergone major changes. This explosion has been ignited by the widespread use of techniques, particularly DNA sequencing, that allow direct assessment of the genetic signature of the phylogeny of birds.” These comments are even more relevant to the nomenclature of birds used in CITES, which still relies on a standard reference from 1975 for the names of orders and families and on another dating from 1997 for the treatment of some species of Psittaciformes.