Comparative Connections a Triannual E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leonardo Helicopters Soar in Philippine Skies

World Trade Centre, Metro Manila, Philippines 28-30 September 2016 DAILY NEWS DAY 2 29 September Leonardo helicopters soar in Philippine skies Elbit builds on M113 work New AFP projects progress Page 8 Changing course? South China Sea The Philippine Navy has ordered two AW159 Wildcat helicopters. (Photo: Leonardo Helicopters) verdict fallout Page 11 and avionics. It is no surprise that both aircraft and helicopters, the STAND 1250 the Philippine Air Force and Navy are Philippines’ strategic posture is Leonardo Helicopters has achieved extremely happy with their AW109s, interesting as it might open a number outstanding recent success in the considering them a step change in of opportunities for collaboration in the Philippine market. For example, the their capabilities.’ naval and air fields.’ Philippine Navy (PN) purchased five Leonardo enjoyed further success The company added: ‘With the navy AW109 Power aircraft and the when the PN ordered two AW159 undergoing modernisation plans, we Philippine Air Force (PAF) eight Wildcats (pictured left) in March. are ready to work with them in the field examples. The spokesperson commented: of naval guns, Heavy ADAS Daily News spoke to a ‘The AW159s were chosen after a such as the best-selling 76/62 metal Leonardo spokesperson about this. competitive selection to respond to Super Rapid gun from our Defence ‘The choice of the AW109 is very a very sophisticated anti-submarine Systems division. Furthermore, we Asia-Pacific AFV interesting because it represents the warfare (ASW) and anti-surface offer a range of ship-based radar and market analysis ambition of the Philippines to truly warfare (ASuW) requirement of the naval combat solutions that might be Page 13 upgrade their capabilities in terms of Philippine Navy. -

MW Voltaire T. Gazmin Grand Master of Masons, MY 2016-2017 the Cable Tow Vol

Special Issue • Our New Grand Master • Grand Lodge Theme for the Year • Plans and Programs • GLP Schedule 2016- 2017 • Masonic Education • The events and Activities of Ancom 2016 • Our New Junior Grand Warden: RW Agapito Suan, Jr. • The new GLP officers and appointees MW Voltaire T. Gazmin Grand Master of Masons, MY 2016-2017 The Cable Tow Vol. 93 Special Issue No. 1 Editor’s Notes In the service of one’s Grand Mother DURING THE GRAND MASTER’S GALA held at the Taal Vista Hotel last April 30, then newly-installed MW Voltaire Gazmin in a hushed voice uttered one of his very first directives as a Grand Master: Let’s come out with a special AnCom issue of The Cable Tow or ELSE! THE LAST TWO WORDS, OF COURSE, IS A across our country’s archipelago and at the same time JOKE! be prompt in the delivery of news and information so needed for the sustenance of the growing craftsman. But our beloved Grand Master did ask for a May issue of the Cable Tow and so he shall have it. Indeed, just as what the Grand Orient directs and as far as Volume 93 is concerned, this publication will This is a special issue of The Cable Tow, which aim to Personify Freemasonry by thinking, writing encases within its pages the events and highlights and publishing articles the Mason’s Way. of the 100th Annual Communications of the Most Worshipful Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted With most of the result of the recent national elections Masons of the Philippines. -

Getting the Philippines Air Force Flying Again: the Role of the U.S.–Philippines Alliance Renato Cruz De Castro, Phd, and Walter Lohman

BACKGROUNDER No. 2733 | SEptEMBER 24, 2012 Getting the Philippines Air Force Flying Again: The Role of the U.S.–Philippines Alliance Renato Cruz De Castro, PhD, and Walter Lohman Abstract or two years, the U.S.– The recent standoff at Scarborough FPhilippines alliance has been Key Points Shoal between the Philippines and challenged in ways unseen since the China demonstrates how Beijing is closure of two American bases on ■■ The U.S. needs a fully capable ally targeting Manila in its strategy of Filipino territory in the early 1990s.1 in the South China Sea to protect U.S.–Philippines interests. maritime brinkmanship. Manila’s China’s aggressive, well-resourced weakness stems from the Philippine pursuit of its territorial claims in ■■ The Philippines Air Force is in a Air Force’s (PAF) lack of air- the South China Sea has brought a deplorable state—it does not have defense system and air-surveillance thousand nautical miles from its the capability to effectively moni- tor, let alone defend, Philippine capabilities to patrol and protect own shores, and very close to the airspace. Philippine airspace and maritime Philippines. ■■ territory. The PAF’s deplorable state For the Philippines, sovereignty, The Philippines has no fighter jets. As a result, it also lacks trained is attributed to the Armed Forces access to energy, and fishing grounds fighter pilots, logistics training, of the Philippines’ single-minded are at stake. For the U.S., its role as and associated basing facilities. focus on internal security since 2001. regional guarantor of peace, secu- ■■ The government of the Philippines Currently, the Aquino administration rity, and freedom of the seas is being is engaged in a serious effort to is undertaking a major reform challenged—as well as its reliability more fully resource its military to shift the PAF from its focus on as an ally. -

Distribution and Nesting Density of the Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga

Ibis (2003), 145, 130–135 BlackwellDistribution Science, Ltd and nesting density of the Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi on Mindanao Island, Philippines: what do we know after 100 years? GLEN LOVELL L. BUESER,1 KHARINA G. BUESER,1 DONALD S. AFAN,1 DENNIS I. SALVADOR,1 JAMES W. GRIER,1,2* ROBERT S. KENNEDY3 & HECTOR C. MIRANDA, JR1,4 1Philippine Eagle Foundation, VAL Learning Village, Ruby Street, Marfori Heights Subd., Davao City 8000 Philippines 2Department of Biological Sciences, North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota 58105, USA 3Maria Mitchell Association, 4 Vestal Street, Nantucket, MA 02554, USA 4University of the Philippines Mindanao, Bago Oshiro, Davao City 8000 Philippines The Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi, first discovered in 1896, is one of the world’s most endangered eagles. It has been reported primarily from only four main islands of the Philippine archipelago. We have studied it extensively for the past three decades. Using data from 1991 to 1998 as best representing the current status of the species on the island of Mindanao, we estimated the mean nearest-neighbour distances between breeding pairs, with remarkably little variation, to be 12.74 km (n = 13 nests plus six pairs without located nests, se = ±0.86 km, range = 8.3–17.5 km). Forest cover within circular plots based on nearest-neighbour pairs, in conjunction with estimates of remaining suitable forest habitat (approximately 14 000 km2), yield estimates of the maximum number of breeding pairs on Mindanao ranging from 82 to 233, depending on how the forest cover is factored into the estimates. The Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi is a large insufficient or unreliable data, and inadequately forest raptor considered to be one of the three reported methods. -

AIR FORCE REVIEW Vol 1, No 1 TAKING OFF

AIR FORCE REVIEW Vol 1, No 1 TAKING OFF Lt Col Jose Tony E Villarete PAF Director, Office of Special Studies In line with the vision of the Commanding General Philippine Air Force, LTGEN BENJAMIN P DEFENSOR JR AFP, of a faster, stronger and better Philippine Air Force, the Office of Special Studies (OSS) has come up with this new version of PAF doctrine and strategy publication. The Air Force Review, successor of the OSS Digest is published quarterly, aims to increase the AFP personnel’s awareness of the existing doctrines of the PAF and activities related to doctrines development and to stimulate discussions about air power, strategic development and matters affecting national security. In an effort to keep pace with the CG’s vision, this maiden issue is an attempt to produce a responsibly faster publication through the dedication and devotion of the reinvigorated editorial staff. Contributions from the major units and the different functional staffs, as well as from the visiting fellows sent to RAAF Aerospace Center, were solicited. Likewise, variety of topics were covered from a wider sources, ensuring a stronger base of ideas for the publication. We continuously strive to come up with articles that would contribute towards better doctrines and strategy, which, separately or collectively, add value to the service the Philippine Air Force provides to the country and people. For this year, the OSS intends to focus on air power awareness through multi- media methodology, doctrine formulation and revision, initiating the review and revisions of the PAF Basic Doctrine, developing a relevant air strategy, and conducting “conceptual” activities such as the CG’s PAF Annual Air Power Symposium, regular publication of the Air Force Review and holding of the Doctrine Family Conference. -

In Camarines

2012 KARAPATAN YEAR-END REPORT ON THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION IN THE PHILIPPINES Cover Design: Tom Estrera III Photo Credits: arkibongbayan.org | bulatlat.com pinoyweekly.org | karapatan.org | Panalipdan KARAPATAN Alliance for the Advancement of People’s Rights 2/F Erythrina Bldg., #1 Maaralin corner Matatag Sts., Barangay Central, Diliman, Quezon City 1100 Philippines Telefax +63 2 4354146 [email protected] | www.karapatan.org CONTENTS 1 Karapatan’s 2012 Human Rights Report 32 The Long Trek to Safety 34 From Ampatuan to Arakan, to Tampakan: Continuing Impunity in Mindanao 44 Imprints of Violence: Shattered Lives and Disrupted Childhood 50 The CCT Con 52 Acronyms Karapatan’s 2012 Human Rights Report he almost complete unmasking to the public of a pretentious rule marks the second Tyear of Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino’s presidency. Despite supposedly improving economic statistics, the majority of the people are still mired in poverty reeling from high prices of basic commodities and services, unemployment, unlivable wages, sham land reform, inadequate housing and so on. Even its much touted campaign against poverty is under question as more cases of corruption by people from the Aquino administration surface. No hope can be pinned on this president whose government fails to lighten and instead adds to the burden that the people, especially from the basic sectors, endure. Noynoy Aquino’s reckless implementation of privatization, liberalization, deregulation and denationalization, all earmarks of neoliberal globalization, proves his puppetry to U.S. imperialism. Just like Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, Aquino has been anointed to be the U.S. lackey in Asia especially in its current “pivot to Asia-Pacific.” In exchange for Obama’s pat on the head and American military aid, Malacanang welcomes stronger U.S. -

Between Rhetoric and Reality: the Progress of Reforms Under the Benigno S. Aquino Administration

Acknowledgement I would like to extend my deepest gratitude, first, to the Institute of Developing Economies-JETRO, for having given me six months from September, 2011 to review, reflect and record my findings on the concern of the study. IDE-JETRO has been a most ideal site for this endeavor and I express my thanks for Executive Vice President Toyojiro Maruya and the Director of the International Exchange and Training Department, Mr. Hiroshi Sato. At IDE, I had many opportunities to exchange views as well as pleasantries with my counterpart, Takeshi Kawanaka. I thank Dr. Kawanaka for the constant support throughout the duration of my fellowship. My stay in IDE has also been facilitated by the continuous assistance of the “dynamic duo” of Takao Tsuneishi and Kenji Murasaki. The level of responsiveness of these two, from the days when we were corresponding before my arrival in Japan to the last days of my stay in IDE, is beyond compare. I have also had the opportunity to build friendships with IDE Researchers, from Nobuhiro Aizawa who I met in another part of the world two in 2009, to Izumi Chibana, one of three people that I could talk to in Filipino, the other two being Takeshi and IDE Researcher, Velle Atienza. Maraming salamat sa inyo! I have also enjoyed the company of a number of other IDE researchers within or beyond the confines of the Institute—Khoo Boo Teik, Kaoru Murakami, Hiroshi Kuwamori, and Sanae Suzuki. I have been privilege to meet researchers from other disciplines or area studies, Masashi Nakamura, Kozo Kunimune, Tatsufumi Yamagata, Yasushi Hazama, Housan Darwisha, Shozo Sakata, Tomohiro Machikita, Kenmei Tsubota, Ryoichi Hisasue, Hitoshi Suzuki, Shinichi Shigetomi, and Tsuruyo Funatsu. -

OH-323) 482 Pgs

Processed by: EWH LEE Date: 10-13-94 LEE, WILLIAM L. (OH-323) 482 pgs. OPEN Military associate of General Eisenhower; organizer of Philippine Air Force under Douglas MacArthur, 1935-38 Interview in 3 parts: Part I: 1-211; Part II: 212-368; Part III: 369-482 DESCRIPTION: [Interview is based on diary entries and is very informal. Mrs. Lee is present and makes occasional comments.] PART I: Identification of and comments about various figures and locations in film footage taken in the Philippines during the 1930's; flying training and equipment used at Camp Murphy; Jimmy Ord; building an airstrip; planes used for training; Lee's background (including early duty assignments; volunteering for assignment to the Philippines); organizing and developing the Philippine Air Unit of the constabulary (including Filipino officer assistants; Curtis Lambert; acquiring training aircraft); arrival of General Douglas MacArthur and staff (October 26, 1935); first meeting with Major Eisenhower (December 14, 1935); purpose of the constabulary; Lee's financial situation; building Camp Murphy (including problems; plans for the air unit; aircraft); Lee's interest in a squadron of airplanes for patrol of coastline vs. MacArthur's plan for seapatrol boats; Sid Huff; establishing the air unit (including determining the kind of airplanes needed; establishing physical standards for Filipino cadets; Jesus Villamor; standards of training; Lee's assessment of the success of Filipino student pilots); "Lefty" Parker, Lee, and Eisenhower's solo flight; early stages in formation -

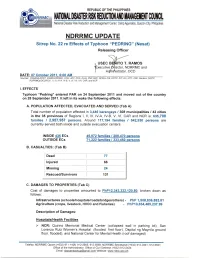

NDRRMC Update Sitrep No. 22 Re Effects of Typhoon PEDRING

Region I: La Paz Community and Medicare Hospital (flooded and non functional) Region II: Southern Isabela General Hospital roofs of Billing sections and Office removed Region III: RHU I of Paombong (roof damaged), Calumpit District Hospital (flooded) and Hagonoy District Hospital (flooded and non functional) Cost of damages on health facilities (infrastructure and equipment) is still being validated by DOH Infrastructure Region III Collapsed Dikes and Creeks in Pampanga - Brgy. Mandili Dike, Brgy. Barangca Dike in Candaba, Matubig Creek, San Jose Dayat Creek, San Juan Gandara, San Agustin Sapang Maragol in Guagua earthdike - (breached) and Brgy. Gatud and Dampe earthdike in Floridablanca - collapsed; slope protection in Brgy. San Pedro Purok 1 (100 m); slope protection in Brgy. Benedicto Purok 1 (300 m); Slope protection in Brgy. Valdez along Gumain River (200 M); and Brgy. Solib Purok 6, Porac River and River dike in Sto. Cristo, Sta. Rosa, Sta. Rita and Sta. Catalina, Lubao, Pampanga. D. DAMAGED HOUSES (Tab D) A total of 51,502 houses were damaged in Regions I, II, III, IV-A, IV-B, V, VI, and CAR (6,825 totally and 44,677 partially) E. STATUS OF LIFELINES: 1. ROADS AND BRIDGES CONDITION (Tab E) A total of 29 bridges/road sections were reported impassable in Region I (1), Region II (7), Region III (13), and CAR (8). F. STATUS OF DAMS (As of 4:00 PM, 06 October 2011) The following dams opened their respective gates as the water levels have reached their spilling levels: Ambuklao (3 Gates / 1.5 m); Binga (2 Gates / 2 m); Magat (1 Gate / 2 m); and San Roque (2 Gates / 1 m) G. -

Department of National Defense Voltaire T. Gazmin

DEPARTMENT OF NATIONAL DEFENSE Camp General Emilio Aguinaldo, Quezon City Metro Manila Area Code: 02 Trunkline: 982-5600 www.dnd.gov.ph VOLTAIRE T. GAZMIN Secretary 982-5600 UNDERSECRETARIES: HONORIO S. AZCUETA Defense Affairs/National Defense loc. 5641 FERNANDO I. MANALO Finance, Munitions, loc. 5675 Installations and Materiel PIO LORENZO F. BATINO Legal & Legislative Affairs loc. 5644 & Strategic Concerns EDUARDO G. BATAC Civil, Veterans and Reserve Affairs loc. 5647 PROCESO T. DOMINGO 912-6675; 912-2424 ASSISTANT SECRETARIES: EFREN Q. FERNANDEZ Personnel loc. 5669 ERNESTO D. BOAC Comptrollership loc. 5663 DANILO AUGUSTO B. FRANCIA Plans & Programs loc. 5696 RAYMUND JOSE G. QUILOP Strategic Assessment loc. 5653 PATRICK M. VELEZ Acquisition, Installations & Logistics 982-5607; loc. 5657 CHIEF OF STAFF: PETER PAUL RUBEN G. GALVEZ 982-5600 EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT: EDITHA B. SANTOS OIC-Defense Acquisition Office loc. 5692 45 ATTACHED AGENCIES GOVERNMENT ARSENAL JONATHAN C. MARTIR Camp Antonio Luna, Limay, Bataan Director IV 911-4580; 421-1554 NATIONAL DEFENSE COLLEGE OF THE PHILIPPINES FERMIN R. DE LEON, JR. LOGCOM Compound, Camp Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo, Quezon City President 911-8469 OFFICE OF CIVIL DEFENSE BENITO T. RAMOS DND, Camp E. Aguinaldo, Quezon City Administrator 912-6675; 912-2424 PHILIPPINE VETERANS AFFAIRS OFFICE ERNESTO G. CAROLINA Camp Emilio Aguinaldo, Quezon City Administrator 912-4526; 986-1906 MILITARY SHRINE SERVICES TERESITA C. CUEVAS PVAO Compound, Camp Aguinaldo, Quezon City Chief 912-4526; 986-1906 VETERANS MEMORIAL MEDICAL CENTER NONA F. LEGASPI North Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City Director 927-1873; 920-2487 ARMED FORCES OF THE PHILIPPINES LT. GEN. JESSIE D. DELLOSA AFP Camp General E. -

Southern Philippines, February 2011

Confirms CORI country of origin research and information CORI Country Report Southern Philippines, February 2011 Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. Any views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of UNHCR. Preface Country of Origin Information (COI) is required within Refugee Status Determination (RSD) to provide objective evidence on conditions in refugee producing countries to support decision making. Quality information about human rights, legal provisions, politics, culture, society, religion and healthcare in countries of origin is essential in establishing whether or not a person’s fear of persecution is well founded. CORI Country Reports are designed to aid decision making within RSD. They are not intended to be general reports on human rights conditions. They serve a specific purpose, collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin, pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. Categories of COI included within this report are based on the most common issues arising from asylum applications made by nationals from the southern Philippines, specifically Mindanao, Tawi Tawi, Basilan and Sulu. This report covers events up to 28 February 2011. COI is a specific discipline distinct from academic, journalistic or policy writing, with its own conventions and protocols of professional standards as outlined in international guidance such as The Common EU Guidelines on Processing Country of Origin Information, 2008 and UNHCR, Country of Origin Information: Towards Enhanced International Cooperation, 2004. CORI provides information impartially and objectively, the inclusion of source material in this report does not equate to CORI agreeing with its content or reflect CORI’s position on conditions in a country. -

Air & Space Power Journal

January–February 2015 Volume 29, No. 1 AFRP 10-1 Senior Leader Perspective A Rebalance Strategy for Pacific Air Forces ❙ 6 Flight Plan to Runways and Relationships Brig Gen Steven L. Basham, USAF Maj Nelson D. Rouleau, USAF Feature Operationalizing Air-Sea Battle in the Pacific ❙ 20 Maj William H. Ballard, USAF Col Mark C. Harysch, USAF, Retired Col Kevin J. Cole, USAF, Retired Byron S. Hall Departments 48 ❙ Views Pacific Air Forces’ Power Projection ❙ 48 Sustaining Peace, Prosperity, and Freedom Lt Col David A. Williamson, USAF Back to the Future ❙ 61 Integrated Air and Missile Defense in the Pacific Kenneth R. Dorner Maj William B. Hartman, USAF Maj Jason M. Teague, USAF To Enable and Sustain ❙ 79 Pacific Air Forces’ Theater Security Cooperation as a Line of Operation Lt Col Jeffrey B. Warner, USAF Empowered Commanders ❙ 99 The Cornerstone to Agile, Flexible Command and Control Maj Eric Theriault, USAF Resilient Airmen ❙ 112 Pacific Air Forces’ Critical Enabler Maj Cody G. Gravitt, USAF Capt Greg Long, USAF Command Chief Harold L. Hutchison, USAF 131 ❙ Commentary Leading Millennials ❙ 131 An Approach That Works Col S. Clinton Hinote, USAF Col Timothy J. Sundvall, USAF 139 ❙ Ricochets & Replies A Global Space Control Strategy ❙ 139 Theresa Hitchens, Former Director, United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research 141 ❙ Book Reviews The Human Factors of Fratricide . 141 Laura A. Rafferty, Neville A. Stanton, and Guy H. Walker Reviewer: Nathan Albright Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Spaceflight . 143 David A. Mindell Reviewer: 2nd Lt Jessica Wong, USAF Lessons from the Hanoi Hilton: Six Characteristics of High-Performance Teams .