Investigations on the Cultivation of Wild Edible Mushroom Macrolepiota Procera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

<I>Lepiota Brunneoincarnata</I>

ISSN (print) 0093-4666 © 2013. Mycotaxon, Ltd. ISSN (online) 2154-8889 MYCOTAXON http://dx.doi.org/10.5248/126.133 Volume 126, pp. 133–141 October–December 2013 Lepiota brunneoincarnata and L. subincarnata: distribution and phylogeny A. Razaq1*, E.C. Vellinga2, S. Ilyas1 & A.N. Khalid1 1Department of Botany, University of the Punjab, Lahore. 54590, Pakistan 2Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of California Berkeley California USA *Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract — An updated phylogeny of the clade of toxic Lepiota species is presented, and new insights in the distribution of L. brunneoincarnata and L. subincarnata are given. Lepiota brunneoincarnata is widespread in Europe and temperate Asia, and L. subincarnata is now known from Asia, Europe, and North America. Morphological and anatomical descriptions are provided for these two species based on material from the western Himalayan forests in Pakistan, where they are reported for the first time. Keywords — amatoxins, lepiotaceous fungi, mushroom diversity, rDNA Introduction Among lepiotaceous fungi the genus Lepiota (Pers.) Gray (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) has a worldwide distribution and is highly diversified (Bon 1993; Ahmad et al. 1997; Vellinga 2003; Kirk et al. 2008; Razaq et al. 2012; Nawaz et al. 2013). The genus is characterized by having a scaly (rarely smooth) pileus, free lamellae, partial veil in the form of annulus, a universal veil, smooth white dextrinoid spores (in most species), and clamp connections (present in all but one or two species) (Vellinga 2001, Kumar & Manimohan 2009). The nature of the pileus covering elements and the spore shape are very important characters for infrageneric classification (Candusso & Lanzoni 1990; Bon 1993; Vellinga 2001, 2003). -

Agaricales, Basidiomycota) Occurring in Punjab, India

Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology 5 (3): 213–247(2015) ISSN 2229-2225 www.creamjournal.org Article CREAM Copyright © 2015 Online Edition Doi 10.5943/cream/5/3/6 Ecology, Distribution Perspective, Economic Utility and Conservation of Coprophilous Agarics (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) Occurring in Punjab, India Amandeep K1*, Atri NS2 and Munruchi K2 1Desh Bhagat College of Education, Bardwal–Dhuri–148024, Punjab, India. 2Department of Botany, Punjabi University, Patiala–147002, Punjab, India. Amandeep K, Atri NS, Munruchi K 2015 – Ecology, Distribution Perspective, Economic Utility and Conservation of Coprophilous Agarics (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) Occurring in Punjab, India. Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology 5(3), 213–247, Doi 10.5943/cream/5/3/6 Abstract This paper includes the results of eco-taxonomic studies of coprophilous mushrooms in Punjab, India. The information is based on the survey to dung localities of the state during the various years from 2007-2011. A total number of 172 collections have been observed, growing as saprobes on dung of various domesticated and wild herbivorous animals in pastures, open areas, zoological parks, and on dung heaps along roadsides or along village ponds, etc. High coprophilous mushrooms’ diversity has been established and a number of rare and sensitive species recorded with the present study. The observed collections belong to 95 species spread over 20 genera and 07 families of the order Agaricales. The present paper discusses the distribution of these mushrooms in Punjab among different seasons, regions, habitats, and growing habits along with their economic utility, habitat management and conservation. This is the first attempt in which various dung localities of the state has been explored systematically to ascertain the diversity, seasonal availability, distribution and ecology of coprophilous mushrooms. -

MYCOTAXON Volume 96, Pp

MYCOTAXON Volume 96, pp. 181–191 April–June 2006 The genus Chlorophyllum (Basidiomycetes) in China Z. W. GE1, 2 & Zhu L. YANG1, * [email protected] [email protected] 1 Laboratory of Biodiversity and Biogeography, Kunming Institute of Botany Chinese Academy of Sciences, Heilongtan, Kunming 650204, Yunnan, P. R. China 2 Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Beijing 100039, P. R. China Abstract—Species of the genus Chlorophyllum (Agaricaceae) in China are described and illustrated with line drawings. Among them, C. sphaerosporum is new to science, and C. hortense is new to China. A key to the Chlorophyllum species in China is also provided. Key words—Agaricales, new taxon, new record, taxonomy, distribution Introduction The genus Chlorophyllum Massee (Agaricaceae, Agaricales, Basidiomycetes) in its amended sense is characterized by a hymenidermal pileus covering, a smooth stipe, and basidiospores without a germ pore or with a germ pore but just caused by a depression in the episporium. A hyaline covering on the germ pore is absent. The basidiospores may be white, green, brownish or brown in deposit, and the habit varies from agaricoid to secotioid (Vellinga 2001, 2002, 2003a, b; Vellinga & de Kok 2002; Vellinga et al. 2003). During our survey of the lepiotoid fungi in China, several species were identified, and one new species of the genus was encountered and thus described below. Differences between similar species are provided and discussed. Material and methods All material examined collected in China, and deposited in three Herbaria. Herbarium codes used follow Holmgren et al. (1990) with one exception: HKAS = Herbarium of Cryptogams, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, which is not listed in the index or relevant publications. -

A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella Species

A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Synopsis Fungorum 8 Fungiflora - Oslo - Norway A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Printed in Eko-trykk A/S, Førde, Norway Printing date: 1. August 1995 ISBN 82-90724-14-4 ISSN 0802-4966 A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Synopsis Fungorum 8 Fungiflora - Oslo - Norway 6 Authors address: Center for Forest Mycology Research Forest Products Laboratory United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service One Gifford Pinchot Dr. Madison, WI 53705 USA ABSTRACT Once a taxonomic refugium for nearly any white-spored agaric with an annulus and attached gills, the concept of the genus Armillaria has been clarified with the neotypification of Armillaria mellea (Vahl:Fr.) Kummer and its acceptance as type species of Armillaria (Fr.:Fr.) Staude. Due to recognition of different type species over the years and an extremely variable generic concept, at least 274 species and varieties have been placed in Armillaria (or in Armillariella Karst., its obligate synonym). Only about forty species belong in the genus Armillaria sensu stricto, while the rest can be placed in forty-three other modem genera. This study is based on original descriptions in the literature, as well as studies of type specimens and generic and species concepts by other authors. This publication consists of an alphabetical listing of all epithets used in Armillaria or Armillariella, with their basionyms, currently accepted names, and other obligate and facultative synonyms. -

2011 NAMA Toxicology Committee Report North American Mushroom Poisonings

2011 NAMA Toxicology Committee Report North American Mushroom Poisonings By Michael W. Beug, PhD, Chair NAMA Toxicology Committee P.O. Box 116, Husum, WA 98623 email: [email protected] Abstract In 2011, for North America, the reports to NAMA included 117 people seriously sickened by mushrooms. Thirteen cases involved ingestion of either “Destroying Angel” or “Death Cap” mushrooms in the genus Amanita. There was one death and two people needed a liver transplant after ingestion of a “Destroying Angel”, presumably Amanita bisporigera. Three cases, including one death, involved amatoxins from a Galerina , presumably Galerina marginata . There was one case of kidney damage after consumption of Amanita smithiana and a second case of kidney damage involving two women who consumed an unknown mushroom . The year was noteworthy for the large number of reports of problems from consumption of morels with 22 cases (18.8% of the total). A number of problems were the result of people consuming morels raw – but everyone recovered within 24 hours. The eighteen Chlorophyllum molybdites cases (15% of the total) were sometimes quite severe and often required hospitalization. While Gyromitra cases numbered only nine (eight Gyromitra esculenta and one Gyromitra montana ), four required long hospitalizations as a result of liver damage. In the Northeast, newspaper reports mention long hospitalizations from some of the mushrooms known to cause gastro- intestinal distress, but we have no information on those cases. Twenty seven reports of dogs ill after eating mushrooms included fourteen deaths of the dogs. The dog deaths were mostly attributed to ingestion of mushrooms containing α-amanitin, including probable Amanita bisporigera, Amanita ocreata and Amanita phalloides , though in at least one case the possibility of a deadly Galerina cannot be ruled out. -

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

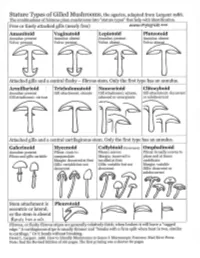

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

Molecular Identification of Lepiota Acutesquamosa and L. Cristata

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURE & BIOLOGY ISSN Print: 1560–8530; ISSN Online: 1814–9596 12–1007/2013/15–2–313–318 http://www.fspublishers.org Full Length Article Molecular Identification of Lepiota acutesquamosa and L. cristata (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) Based on ITS-rDNA Barcoding from Himalayan Moist Temperate Forests of Pakistan Abdul Razaq1*, Abdul Nasir Khalid1 and Sobia Ilyas1 1Department of Botany, University of the Punjab, Lahore 54590, Pakistan *For correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Lepiota acutesquamosa and L. cristata (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) collected from Himalayan moist temperate forests of Pakistan were characterized using internal transcribed spacers (ITS) of rNDA, a fungal molecular marker. The ITS-rDNA of both species was analyzed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA sequencing. The target region when amplified using universal fungal primers (ITS1F and ITS4) generated 650-650bp fragments. Consensus sequences of both species were submitted for initial blast analysis which revealed and confirmed the identification of both species by comparing the sequences of these respective species already present in the GenBank. Sequence of Pakistani collection of L. acutesquamosa matched 99% with sequences of same species (FJ998400) and Pakistani L. cristata matched 97% with its sequences (EU081956, U85327, AJ237628). Further, in phylogenetic analysis both species distinctly clustered with their respective groups. Morphological characters like shape, size and color of basidiomata, basidiospore size, basidial lengths, shape and size of cheilocystidia of both collections were measured and compared. Both these species have been described first time from Pakistan on morph-anatomical and molecular basis. © 2013 Friends Science Publishers Keywords: Internal transcribed spacers; Lepiotaceous fungi; Molecular marker; Phylogeny Introduction of lepiotaceous fungi (Vellinga, 2001, 2003, 2006). -

Lepiotoid Agaricaceae (Basidiomycota) from São Camilo State Park, Paraná State, Brazil

Mycosphere Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/3/6/11 Lepiotoid Agaricaceae (Basidiomycota) from São Camilo State Park, Paraná State, Brazil Ferreira AJ1* and Cortez VG1 1Universidade Federal do Paraná, Rua Pioneiro 2153, Jardim Dallas, 85950-000, Palotina, PR, Brazil Ferreira AJ, Cortez VG 2012 – Lepiotoid Agaricaceae (Basidiomycota) from São Camilo State Park, Paraná State, Brazil. Mycosphere 3(6), 962–976, Doi 10.5943 /mycosphere/3/6/11 A macromycete survey at the São Camilo State Park, a seasonal semideciduous forest fragment in Southern Brazil, State of Paraná, was undertaken. Six lepiotoid fungi were identified: Lepiota elaiophylla, Leucoagaricus lilaceus, L. rubrotinctus, Leucocoprinus cretaceus, Macrolepiota colombiana and Rugosospora pseudorubiginosa. Detailed descriptions and illustrations are presented for all species, as well as a brief discussion on their taxonomy and geographical distribution. Macrolepiota colombiana is reported for the first time in Brazil and Leucoagaricus rubrotinctus is a new record from the State of Paraná. Key words – Agaricales – Brazilian mycobiota – new records Article Information Received 30 October 2012 Accepted 14 November 2012 Published online 3 December 2012 *Corresponding author: Ana Júlia Ferreira – e-mail: [email protected] Introduction who visited and/or studied collections from the Agaricaceae Chevall. (Basidiomycota) country in the 19th century. More recently, comprises the impressive number of 1340 researchers have studied agaricoid diversity in species, classified in 85 agaricoid, gasteroid the Northeast (Wartchow et al. 2008), and secotioid genera (Kirk et al. 2008), and Southeast (Capelari & Gimenes 2004, grouped in ten clades (Vellinga 2004). The Albuquerque et al. 2010) and South (Rother & family is of great economic and medical Silveira 2008, 2009a, 2009b). -

Forest Fungi in Ireland

FOREST FUNGI IN IRELAND PAUL DOWDING and LOUIS SMITH COFORD, National Council for Forest Research and Development Arena House Arena Road Sandyford Dublin 18 Ireland Tel: + 353 1 2130725 Fax: + 353 1 2130611 © COFORD 2008 First published in 2008 by COFORD, National Council for Forest Research and Development, Dublin, Ireland. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from COFORD. All photographs and illustrations are the copyright of the authors unless otherwise indicated. ISBN 1 902696 62 X Title: Forest fungi in Ireland. Authors: Paul Dowding and Louis Smith Citation: Dowding, P. and Smith, L. 2008. Forest fungi in Ireland. COFORD, Dublin. The views and opinions expressed in this publication belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of COFORD. i CONTENTS Foreword..................................................................................................................v Réamhfhocal...........................................................................................................vi Preface ....................................................................................................................vii Réamhrá................................................................................................................viii Acknowledgements...............................................................................................ix -

Heavy Metals Content and the Role of Lepiota Cristata As Antioxidant in Oxidative Stress

Journal of Bacteriology & Mycology: Open Access Research Article Open Access Heavy metals content and the role of Lepiota cristata as antioxidant in oxidative stress Abstract Volume 6 Issue 4 - 2018 The present study aimed to determine antioxidant/oxidant potential and heavy metal content of Lepiota cristata (Bolton) P. kumm. Total antioxidant status (TAS), total oxidant Mustafa Sevindik status (TOS) and oxidative stress index (OSI) of the mushroom were determined using Rel Department of Biology, Akdeniz University, Turkey Assay kits. Fe, Zn, Cu, Pb and Ni content were measured by a wet decomposition method using a Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 400 AA spectrometer. The study findings demonstrated Correspondence: Mustafa Sevindik, Faculty of Science, that TAS value of L. cristata was 2.210±0.068, TOS value was 24.357±0.129 and OSI was Department of Biology, Akdeniz University, Turkey, Email [email protected] 1.103±0.030. It was also determined that Fe content was 381.07±4.847, Zn content was 73.93±2.078, Cu content was 14.16±0.876, Pb content was 8.517±0.623, and Ni content Received: June 03, 2018 | Published: July 13, 2018 was 3.09±0.30. Thus, it was determined that the mushroom had antioxidant potential. However, due to the high oxidant content, it was considered that the mushroom could only be used as an antioxidant source by collecting samples that grow in adequate regions where the mushroom exhibits low oxidative stress index after determination of the compounds with antioxidant effect in these samples. Furthermore, it was determined that L. cristata Fe, Zn and Ni content were within the ranges reported previously in the literature, however Cu content was lower and Pb content was higher when compared to the ranges reported in the literature. -

Adaptability to Submerged Culture and Amtno Acid Contents of Certain Fleshy Fungi Common in Finland

Adaptability to submerged culture and amtno acid contents of certain fleshy fungi common in Finland Mar j a L i is a H a t t u l a and H . G. G y ll e n b e r g Department of Microbiology, University of Helsinki, Finland The literature on the possibilities of sub must be considered when the suitability of merged culture of macrofungi is already fungi for submerged production is evaluated. voluminous. However, the interest has merely The present work concerns a collection of been restricted to the traditionally most va fungi common in Finland which have been lued fungi, particularly members of the gene investigated according to the criteria descri ra Agaricus and M orchella (HuMFELD, 1948, bed above. 1952, HuMFELD & SuGIHARA, 1949, 1952, Su GIHARA & HuMFELD, 1954, SzuEcs 1956, LITCHFIELD, 1964, 1967 a, b, LITCHFIELD & al., MATERIAL 1963) . The information obtainable from stu dies on these organisms is not especially en The material consisted of 33 species of fun couraging because the rate of biomass pro gi, 29 of which were obtained from the duction seems to be too low to compete fa Department of Silviculture, University of ,·ourably with other alternatives of single cell Helsinki, through the courtesy of Professor P. protein production (LITCHFIELD, 1967 a, b). Mikola and Mr. 0 . Laiho. Four species were On the other hand, the traditional use of fun isolated by the present authors by taking a gi as human food all over the world is a sterile piece of the fruiting body at the point significant reason for continued research on where the cap and the stem are joined and the submerged production o.f fungal mycel by transferring it on a slant of suitable agar. -

Research Article

Marwa H. E. Elnaiem et al / Int. J. Res. Ayurveda Pharm. 8 (Suppl 3), 2017 Research Article www.ijrap.net MORPHOLOGICAL AND MOLECULAR CHARACTERIZATION OF WILD MUSHROOMS IN KHARTOUM NORTH, SUDAN Marwa H. E. Elnaiem 1, Ahmed A. Mahdi 1,3, Ghazi H. Badawi 2 and Idress H. Attitalla 3* 1Department of Botany & Agric. Biotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Khartoum, Sudan 2Department of Agronomy, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Khartoum, Sudan 3Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Omar Al-Mukhtar University, Beida, Libya Received on: 26/03/17 Accepted on: 20/05/17 *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.7897/2277-4343.083197 ABSTRACT In a study of the diversity of wild mushrooms in Sudan, fifty-six samples were collected from various locations in Sharq Elneel and Shambat areas of Khartoum North. Based on ten morphological characteristics, the samples were assigned to fifteen groups, each representing a distinct species. Eleven groups were identified to species level, while the remaining four could not, and it is suggested that they are Agaricales sensu Lato. The most predominant species was Chlorophylum molybdites (15 samples). The identified species belonged to three orders: Agaricales, Phallales and Polyporales. Agaricales was represented by four families (Psathyrellaceae, Lepiotaceae, Podaxaceae and Amanitaceae), but Phallales and Polyporales were represented by only one family each (Phallaceae and Hymenochaetaceae, respectively), each of which included a single species. The genetic diversity of the samples was studied by the RAPD-PCR technique, using six random 10-nucleotide primers. Three of the primers (OPL3, OPL8 and OPQ1) worked on fifty-two of the fifty-six samples and gave a total of 140 bands.