Looking for Lepiota Psalion Huijser & Vellinga (Agaricales, Agaricaceae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks Bioblitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of BioBlitz participants conducting data entry into iNaturalist. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service. ON THE COVER Photograph of BioBlitz participants collecting aquatic species data in the Presidio of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service. The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 Elizabeth Edson1, Michelle O’Herron1, Alison Forrestel2, Daniel George3 1Golden Gate Parks Conservancy Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94129 2National Park Service. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1061 Sausalito, CA 94965 3National Park Service. San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program Manager Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1063 Sausalito, CA 94965 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Phylogeny of the Pluteaceae (Agaricales, Basidiomycota): Taxonomy and Character Evolution

AperTO - Archivio Istituzionale Open Access dell'Università di Torino Phylogeny of the Pluteaceae (Agaricales, Basidiomycota): taxonomy and character evolution This is the author's manuscript Original Citation: Availability: This version is available http://hdl.handle.net/2318/74776 since 2016-10-06T16:59:44Z Published version: DOI:10.1016/j.funbio.2010.09.012 Terms of use: Open Access Anyone can freely access the full text of works made available as "Open Access". Works made available under a Creative Commons license can be used according to the terms and conditions of said license. Use of all other works requires consent of the right holder (author or publisher) if not exempted from copyright protection by the applicable law. (Article begins on next page) 23 September 2021 This Accepted Author Manuscript (AAM) is copyrighted and published by Elsevier. It is posted here by agreement between Elsevier and the University of Turin. Changes resulting from the publishing process - such as editing, corrections, structural formatting, and other quality control mechanisms - may not be reflected in this version of the text. The definitive version of the text was subsequently published in FUNGAL BIOLOGY, 115(1), 2011, 10.1016/j.funbio.2010.09.012. You may download, copy and otherwise use the AAM for non-commercial purposes provided that your license is limited by the following restrictions: (1) You may use this AAM for non-commercial purposes only under the terms of the CC-BY-NC-ND license. (2) The integrity of the work and identification of the author, copyright owner, and publisher must be preserved in any copy. -

<I>Lepiota Brunneoincarnata</I>

ISSN (print) 0093-4666 © 2013. Mycotaxon, Ltd. ISSN (online) 2154-8889 MYCOTAXON http://dx.doi.org/10.5248/126.133 Volume 126, pp. 133–141 October–December 2013 Lepiota brunneoincarnata and L. subincarnata: distribution and phylogeny A. Razaq1*, E.C. Vellinga2, S. Ilyas1 & A.N. Khalid1 1Department of Botany, University of the Punjab, Lahore. 54590, Pakistan 2Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of California Berkeley California USA *Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract — An updated phylogeny of the clade of toxic Lepiota species is presented, and new insights in the distribution of L. brunneoincarnata and L. subincarnata are given. Lepiota brunneoincarnata is widespread in Europe and temperate Asia, and L. subincarnata is now known from Asia, Europe, and North America. Morphological and anatomical descriptions are provided for these two species based on material from the western Himalayan forests in Pakistan, where they are reported for the first time. Keywords — amatoxins, lepiotaceous fungi, mushroom diversity, rDNA Introduction Among lepiotaceous fungi the genus Lepiota (Pers.) Gray (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) has a worldwide distribution and is highly diversified (Bon 1993; Ahmad et al. 1997; Vellinga 2003; Kirk et al. 2008; Razaq et al. 2012; Nawaz et al. 2013). The genus is characterized by having a scaly (rarely smooth) pileus, free lamellae, partial veil in the form of annulus, a universal veil, smooth white dextrinoid spores (in most species), and clamp connections (present in all but one or two species) (Vellinga 2001, Kumar & Manimohan 2009). The nature of the pileus covering elements and the spore shape are very important characters for infrageneric classification (Candusso & Lanzoni 1990; Bon 1993; Vellinga 2001, 2003). -

Major Clades of Agaricales: a Multilocus Phylogenetic Overview

Mycologia, 98(6), 2006, pp. 982–995. # 2006 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 Major clades of Agaricales: a multilocus phylogenetic overview P. Brandon Matheny1 Duur K. Aanen Judd M. Curtis Laboratory of Genetics, Arboretumlaan 4, 6703 BD, Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, Wageningen, The Netherlands Worcester, Massachusetts, 01610 Matthew DeNitis Vale´rie Hofstetter 127 Harrington Way, Worcester, Massachusetts 01604 Department of Biology, Box 90338, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 Graciela M. Daniele Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biologı´a Vegetal, M. Catherine Aime CONICET-Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba, Casilla USDA-ARS, Systematic Botany and Mycology de Correo 495, 5000 Co´rdoba, Argentina Laboratory, Room 304, Building 011A, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Beltsville, Maryland 20705-2350 Dennis E. Desjardin Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, Jean-Marc Moncalvo San Francisco, California 94132 Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, Royal Ontario Museum and Department of Botany, University Bradley R. Kropp of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C6 Canada Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322 Zai-Wei Ge Zhu-Liang Yang Lorelei L. Norvell Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Pacific Northwest Mycology Service, 6720 NW Skyline Sciences, Kunming 650204, P.R. China Boulevard, Portland, Oregon 97229-1309 Jason C. Slot Andrew Parker Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, 127 Raven Way, Metaline Falls, Washington 99153- Worcester, Massachusetts, 01609 9720 Joseph F. Ammirati Else C. Vellinga University of Washington, Biology Department, Box Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, 111 355325, Seattle, Washington 98195 Koshland Hall, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-3102 Timothy J. -

Basidiomycota: Agaricales) Introducing the Ant-Associated Genus Myrmecopterula Gen

Leal-Dutra et al. IMA Fungus (2020) 11:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s43008-019-0022-6 IMA Fungus RESEARCH Open Access Reclassification of Pterulaceae Corner (Basidiomycota: Agaricales) introducing the ant-associated genus Myrmecopterula gen. nov., Phaeopterula Henn. and the corticioid Radulomycetaceae fam. nov. Caio A. Leal-Dutra1,5, Gareth W. Griffith1* , Maria Alice Neves2, David J. McLaughlin3, Esther G. McLaughlin3, Lina A. Clasen1 and Bryn T. M. Dentinger4 Abstract Pterulaceae was formally proposed to group six coralloid and dimitic genera: Actiniceps (=Dimorphocystis), Allantula, Deflexula, Parapterulicium, Pterula, and Pterulicium. Recent molecular studies have shown that some of the characters currently used in Pterulaceae do not distinguish the genera. Actiniceps and Parapterulicium have been removed, and a few other resupinate genera were added to the family. However, none of these studies intended to investigate the relationship between Pterulaceae genera. In this study, we generated 278 sequences from both newly collected and fungarium samples. Phylogenetic analyses supported with morphological data allowed a reclassification of Pterulaceae where we propose the introduction of Myrmecopterula gen. nov. and Radulomycetaceae fam. nov., the reintroduction of Phaeopterula, the synonymisation of Deflexula in Pterulicium, and 53 new combinations. Pterula is rendered polyphyletic requiring a reclassification; thus, it is split into Pterula, Myrmecopterula gen. nov., Pterulicium and Phaeopterula. Deflexula is recovered as paraphyletic alongside several Pterula species and Pterulicium, and is sunk into the latter genus. Phaeopterula is reintroduced to accommodate species with darker basidiomes. The neotropical Myrmecopterula gen. nov. forms a distinct clade adjacent to Pterula, and most members of this clade are associated with active or inactive attine ant nests. -

A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella Species

A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Synopsis Fungorum 8 Fungiflora - Oslo - Norway A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Printed in Eko-trykk A/S, Førde, Norway Printing date: 1. August 1995 ISBN 82-90724-14-4 ISSN 0802-4966 A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Synopsis Fungorum 8 Fungiflora - Oslo - Norway 6 Authors address: Center for Forest Mycology Research Forest Products Laboratory United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service One Gifford Pinchot Dr. Madison, WI 53705 USA ABSTRACT Once a taxonomic refugium for nearly any white-spored agaric with an annulus and attached gills, the concept of the genus Armillaria has been clarified with the neotypification of Armillaria mellea (Vahl:Fr.) Kummer and its acceptance as type species of Armillaria (Fr.:Fr.) Staude. Due to recognition of different type species over the years and an extremely variable generic concept, at least 274 species and varieties have been placed in Armillaria (or in Armillariella Karst., its obligate synonym). Only about forty species belong in the genus Armillaria sensu stricto, while the rest can be placed in forty-three other modem genera. This study is based on original descriptions in the literature, as well as studies of type specimens and generic and species concepts by other authors. This publication consists of an alphabetical listing of all epithets used in Armillaria or Armillariella, with their basionyms, currently accepted names, and other obligate and facultative synonyms. -

INTRODUCTION Biodiversity of Agaricomycetes Basidiomes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CONICET Digital DARWINIANA, nueva serie 1(1): 67-75. 2013 Versión final, efectivamente publicada el 31 de julio de 2013 ISSN 0011-6793 impresa - ISSN 1850-1699 en línea BIODIVERSITY OF AGARICOMYCETES BASIDIOMES ASSOCIATED TO SALIX AND POPULUS (SALICACEAE) PLANTATIONS Gonzalo M. Romano1, Javier A. Calcagno2 & Bernardo E. Lechner1 1Laboratorio de Micología, Fitopatología y Liquenología, Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Experimental, Programa de Plantas Medicinales y Programa de Hongos que Intervienen en la Degradación Biológica (CONICET), Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Intendente Güiraldes 2160, Pabellón II, Piso 4, Laboratorio 7, C1428EGA Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina; [email protected] (author for correspondence). 2Centro de Estudios Biomédicos, Biotecnológicos, Ambientales y de Diagnóstico - Departamento de Ciencias Natu- rales y Antropológicas, Instituto Superior de Investigaciones, Hidalgo 775, C1405BCK Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Abstract. Romano, G. M.; J. A. Calcagno & B. E. Lechner. 2013. Biodiversity of Agaricomycetes basidiomes asso- ciated to Salix and Populus (Salicaceae) plantations. Darwiniana, nueva serie 1(1): 67-75. Although plantations have an artificial origin, they modify environmental conditions that can alter native fungi diversity. The effects of forest management practices on a plantation of willow (Salix) and poplar (Populus) over Agaricomycetes basidiomes biodiversity were studied for one year in an island located in Paraná Delta, Argentina. Dry weight and number of basidiomes were measured. We found 28 species belonging to Agaricomycetes: 26 species of Agaricales, one species of Polyporales and one species of Russulales. -

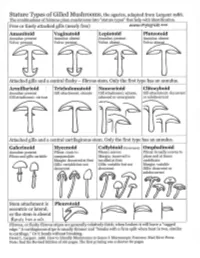

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

Molecular Identification of Lepiota Acutesquamosa and L. Cristata

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURE & BIOLOGY ISSN Print: 1560–8530; ISSN Online: 1814–9596 12–1007/2013/15–2–313–318 http://www.fspublishers.org Full Length Article Molecular Identification of Lepiota acutesquamosa and L. cristata (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) Based on ITS-rDNA Barcoding from Himalayan Moist Temperate Forests of Pakistan Abdul Razaq1*, Abdul Nasir Khalid1 and Sobia Ilyas1 1Department of Botany, University of the Punjab, Lahore 54590, Pakistan *For correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Lepiota acutesquamosa and L. cristata (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) collected from Himalayan moist temperate forests of Pakistan were characterized using internal transcribed spacers (ITS) of rNDA, a fungal molecular marker. The ITS-rDNA of both species was analyzed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA sequencing. The target region when amplified using universal fungal primers (ITS1F and ITS4) generated 650-650bp fragments. Consensus sequences of both species were submitted for initial blast analysis which revealed and confirmed the identification of both species by comparing the sequences of these respective species already present in the GenBank. Sequence of Pakistani collection of L. acutesquamosa matched 99% with sequences of same species (FJ998400) and Pakistani L. cristata matched 97% with its sequences (EU081956, U85327, AJ237628). Further, in phylogenetic analysis both species distinctly clustered with their respective groups. Morphological characters like shape, size and color of basidiomata, basidiospore size, basidial lengths, shape and size of cheilocystidia of both collections were measured and compared. Both these species have been described first time from Pakistan on morph-anatomical and molecular basis. © 2013 Friends Science Publishers Keywords: Internal transcribed spacers; Lepiotaceous fungi; Molecular marker; Phylogeny Introduction of lepiotaceous fungi (Vellinga, 2001, 2003, 2006). -

Fruiting Body Form, Not Nutritional Mode, Is the Major Driver of Diversification in Mushroom-Forming Fungi

Fruiting body form, not nutritional mode, is the major driver of diversification in mushroom-forming fungi Marisol Sánchez-Garcíaa,b, Martin Rybergc, Faheema Kalsoom Khanc, Torda Vargad, László G. Nagyd, and David S. Hibbetta,1 aBiology Department, Clark University, Worcester, MA 01610; bUppsala Biocentre, Department of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SE-75005 Uppsala, Sweden; cDepartment of Organismal Biology, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, 752 36 Uppsala, Sweden; and dSynthetic and Systems Biology Unit, Institute of Biochemistry, Biological Research Center, 6726 Szeged, Hungary Edited by David M. Hillis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, and approved October 16, 2020 (received for review December 22, 2019) With ∼36,000 described species, Agaricomycetes are among the and the evolution of enclosed spore-bearing structures. It has most successful groups of Fungi. Agaricomycetes display great di- been hypothesized that the loss of ballistospory is irreversible versity in fruiting body forms and nutritional modes. Most have because it involves a complex suite of anatomical features gen- pileate-stipitate fruiting bodies (with a cap and stalk), but the erating a “surface tension catapult” (8, 11). The effect of gas- group also contains crust-like resupinate fungi, polypores, coral teroid fruiting body forms on diversification rates has been fungi, and gasteroid forms (e.g., puffballs and stinkhorns). Some assessed in Sclerodermatineae, Boletales, Phallomycetidae, and Agaricomycetes enter into ectomycorrhizal symbioses with plants, Lycoperdaceae, where it was found that lineages with this type of while others are decayers (saprotrophs) or pathogens. We constructed morphology have diversified at higher rates than nongasteroid a megaphylogeny of 8,400 species and used it to test the following lineages (12). -

Download Download

LITERATURE UPDATE FOR TEXAS FLESHY BASIDIOMYCOTA WITH NEW VOUCHERED RECORDS FOR SOUTHEAST TEXAS David P. Lewis Clark L. Ovrebo N. Jay Justice 262 CR 3062 Department of Biology 16055 Michelle Drive Newton, Texas 75966, U.S.A. University of Central Oklahoma Alexander, Arkansas 72002, U.S.A. [email protected] Edmond, Oklahoma 73034, U.S.A. [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT This is a second paper documenting the literature records for Texas fleshy basidiomycetous fungi and includes both older literature and recently published papers. We report 80 literature articles which include 14 new taxa described from Texas. We also report on 120 new records of fleshy basdiomycetous fungi collected primarily from southeast Texas. RESUMEN Este es un segundo artículo que documenta el registro de nuevas especies de hongos carnosos basidiomicetos, incluyendo artículos antiguos y recientes. Reportamos 80 artículos científicamente relacionados con estas especies que incluyen 14 taxones con holotipos en Texas. Así mismo, reportamos unos 120 nuevos registros de hongos carnosos basidiomicetos recolectados primordialmente en al sureste de Texas. PART I—MYCOLOGICAL LITERATURE ON TEXAS FLESHY BASIDIOMYCOTA Lewis and Ovrebo (2009) previously reported on literature for Texas fleshy Basidiomycota and also listed new vouchered records for Texas of that group. Presented here is an update to the listing which includes literature published since 2009 and also includes older references that we previously had not uncovered. The authors’ primary research interests center around gilled mushrooms and boletes so perhaps the list that follows is most complete for the fungi of these groups. We have, however, attempted to locate references for all fleshy basidio- mycetous fungi. -

Three New Species of Cortinarius Subgenus Telamonia (Cortinariaceae, Agaricales) from China

A peer-reviewed open-access journal MycoKeys 69: 91–109 (2020) Three new species in Cortinarius from China 91 doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.69.49437 RESEARCH ARTICLE MycoKeys http://mycokeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Three new species of Cortinarius subgenus Telamonia (Cortinariaceae, Agaricales) from China Meng-Le Xie1,2, Tie-Zheng Wei3, Yong-Ping Fu2, Dan Li2, Liang-Liang Qi4, Peng-Jie Xing2, Guo-Hui Cheng5,2, Rui-Qing Ji2, Yu Li2,1 1 Life Science College, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130024, China 2 Engineering Research Cen- ter of Edible and Medicinal Fungi, Ministry of Education, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun 130118, China 3 State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China 4 Microbiology Research Institute, Guangxi Academy of Agriculture Sciences, Nanning, 530007, China 5 College of Plant Protection, Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang 110866, China Corresponding authors: Rui-Qing Ji ([email protected]), Yu Li ([email protected]) Academic editor: O. Raspé | Received 16 December 2019 | Accepted 23 June 2020 | Published 14 July 2020 Citation: Xie M-L, Wei T-Z, Fu Y-P, Li D, Qi L-L, Xing P-J, Cheng G-H, Ji R-Q, Li Y (2020) Three new species of Cortinarius subgenus Telamonia (Cortinariaceae, Agaricales) from China. MycoKeys 69: 91–109. https://doi. org/10.3897/mycokeys.69.49437 Abstract Cortinarius is an important ectomycorrhizal genus that forms a symbiotic relationship with certain trees, shrubs and herbs. Recently, we began studying Cortinarius in China and here we describe three new spe- cies of Cortinarius subg. Telamonia based on morphological and ecological characteristics, together with phylogenetic analyses.