The University of Liverpool Racism, Tolerance and Identity: Responses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leeds Civic Trust Newsletter April 2020 Message From

OUTLOOK LEEDS CIVIC TRUST NEWSLETTER APRIL 2020 MESSAGE FROM MARTIN The Trust Director writes a special piece about our response to the current Covid-19 pandemic. SEE PAGE 2 PLANNING NEWS Technology allows our Planning Committee to keep ‘meeting’ with Mike Piet on the line to report. SEE PAGE 4 WASTE NOT Claude Saint Arroman considers what we throw away after a visit to Martin HW Waste facility. SEE PAGE 6 MERCURY RETROGRADE Roderic Parker reports on a Trust visit to a printers with a collection of very special vintage postcards. SEE PAGE 8 KEITH WATERHOUSE HONOURED The Hunslet born author and journalist now has his own blue plaque. SEE PAGE 10 ALTHOUGHWHERE WAS THE THIS OFFICE PHOTO IS TAKENCURRENTLY FROM? CLOSED, FIND OUT A RAINBOW IN NEXT MONTH’S HAS APPEARED OUTLOOK... IN ITS WINDOW. ENCOURAGING DEVELOPMENT CONSERVING AND ENHANCING PROMOTING THE IMPROVEMENT THAT IS A SOURCE OF PRIDE THE HERITAGE OF LEEDS OF PUBLIC AMENITIES 2 APRIL 2020 A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR A message from Trust Director, Martin, regarding the Trust’s response to Covid-19. It doesn’t need me to tell you that these are extraordinary times. Back in January we were looking forward to a full year here at the Trust. Events were being finalised, a full schedule of blue plaque unveilings scheduled, our spring season of corporate lunches with a new caterer booked and plans to implement our five year Vision were progressing. We now have the proofs for the much- anticipated second Blue Plaques book, and we were looking forward to launch this in late Spring. -

Pakistanis, Irish, and the Shaping of Multiethnic West Yorkshire, 1845-1985

“Black” Strangers in the White Rose County: Pakistanis, Irish, and the Shaping of Multiethnic West Yorkshire, 1845-1985 An honors thesis for the Department of History Sarah Merritt Mass Tufts University, 2009 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Section One – The Macrocosm and Microcosm of Immigration 9 Section Two – The Dialogue Between “Race” and “Class” 28 Section Three – The Realization of Social and Cultural Difference 47 Section Four – “Multicultural Britain” in Action 69 Conclusion 90 Bibliography 99 ii Introduction Jess Bhamra – the protagonist in the 2002 film Bend It Like Beckham about a Hounslow- born, football-playing Punjabi Sikh girl – is ejected from an important match after shoving an opposing player on the pitch. When her coach, Joe, berates her for this action, Jess retorts with, “She called me a Paki, but I guess you wouldn’t understand what that feels like, would you?” After letting the weight of Jess’s frustration and anger sink in, Joe responds, “Jess, I’m Irish. Of course I understand what that feels like.” This exchange highlights the shared experiences of immigrants from Ireland and those from the Subcontinent in contemporary Britain. Bend It Like Beckham is not the only film to join explicitly these two ethnic groups in the British popular imagination. Two years later, Ken Loach’s Ae Fond Kiss confronted the harsh realities of the possibility of marriage between a man of Pakistani heritage and an Irish woman, using the importance of religion in both cases as a hindrance to their relationship. Ae Fond Kiss recognizes the centrality of Catholicism and Islam to both of these ethnic groups, and in turn how religion defined their identity in the eyes of the British community as a whole. -

Reach PLC Summary Response to the Digital Markets Taskforce Call for Evidence

Reach PLC summary response to the Digital Markets Taskforce call for evidence Introduction Reach PLC is the largest national and regional news publisher in the UK, with influential and iconic brands such as the Daily Mirror, Daily Express, Sunday People, Daily Record, Daily Star, OK! and market leading regional titles including the Manchester Evening News, Liverpool Echo, Birmingham Mail and Bristol Post. Our network of over 70 websites provides 24/7 coverage of news, sport and showbiz stories, with over one billion views every month. Last year we sold 620 million newspapers, and we over 41 million people every month visit our websites – more than any other newspaper publisher in the UK. Changes to the Reach business Earlier this month we announced changes to the structure of our organisation to protect our news titles. This included plans to reduce our workforce from its current level of 4,700 by around 550 roles, gearing our cost base to the new market conditions resulting from the pandemic. These plans are still in consultation but are likely to result in the loss of over 300 journalist roles within the Reach business across national, regional and local titles. Reach accepts that consumers will continue to shift to its digital products, and digital growth is central to our future strategy. However, our ability to monetise our leading audience is significantly impacted by the domination of the advertising market by the leading tech platforms. Moreover, as a publisher of scale with a presence across national, regional and local markets, we have an ability to adapt and achieve efficiencies in the new market conditions that smaller local publishers do not. -

Sheet1 Page 1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen

Sheet1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen - Press & Journal 71,044 Dundee Courier & Advertiser 61,981 Norwich - Eastern Daily Press 59,490 Belfast Telegraph 59,319 Shropshire Star 55,606 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Evening Chronicle 52,486 Glasgow - Evening Times 52,400 Leicester Mercury 51,150 The Sentinel 50,792 Aberdeen - Evening Express 47,849 Birmingham Mail 47,217 Irish News - Morning 43,647 Hull Daily Mail 43,523 Portsmouth - News & Sports Mail 41,442 Darlington - The Northern Echo 41,181 Teesside - Evening Gazette 40,546 South Wales Evening Post 40,149 Edinburgh - Evening News 39,947 Leeds - Yorkshire Post 39,698 Bristol Evening Post 38,344 Sheffield Star & Green 'Un 37,255 Leeds - Yorkshire Evening Post 36,512 Nottingham Post 35,361 Coventry Telegraph 34,359 Sunderland Echo & Football Echo 32,771 Cardiff - South Wales Echo - Evening 32,754 Derby Telegraph 32,356 Southampton - Southern Daily Echo 31,964 Daily Post (Wales) 31,802 Plymouth - Western Morning News 31,058 Southend - Basildon - Castle Point - Echo 30,108 Ipswich - East Anglian Daily Times 29,932 Plymouth - The Herald 29,709 Bristol - Western Daily Press 28,322 Wales - The Western Mail - Morning 26,931 Bournemouth - The Daily Echo 26,818 Bradford - Telegraph & Argus 26,766 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Journal 26,280 York - The Press 25,989 Grimsby Telegraph 25,974 The Argus Brighton 24,949 Dundee Evening Telegraph 23,631 Ulster - News Letter 23,492 South Wales Argus - Evening 23,332 Lancashire Telegraph - Blackburn 23,260 -

Course Proposals 97-8

אוניברסיטת בן-גוריון בנגב BEN-GURION UNIVERSITY OF THE NEGEV FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES ABRAHAMS-CURIEL DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LITERATURES AND LINGUISTICS Professor Efraim Sicher THE POSTWAR BRITISH NOVEL THIRD YEAR SEMINAR 4 PTS MONDAYS AND THURSDAYS 14-16 FIRST SEMESTER Course Description Postwar British prose fiction reflects the changes in society, politics and literature since 1945. From the postwar new wave to post-colonialism, from the Angry Young Man to postmodernism, we look at the best writers of the last 70 years. Course objectives This course gives students knowledge of basic concepts in postwar British fiction in the context of postmodernism. It provokes basic questions about the relation of fiction and truth, history and literature. Keywords: Britain 1945-2020; postmodernism; history; fiction. Course requirements Active participation required 4 Preparatory questions 20% 1 Seminar Paper 15-18 pages 40% (due March 10). 1 Presentation (to be handed in as a 5-6 page written paper by March 10) 40% Required Reading George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four William Golding, Lord of the Flies Ian McEwan, Atonement Salman Rushdie Midnight's Children Norton Anthology of English Literature, volume 2 Additional texts (choose one for presentation) The campus novel (Kingsley Amis, Lucky Jim) Dystopia now (Anthony Burgess, Clockwork Orange) Anger and after (Keith Waterhouse, Billy Liar; Alan Sillitoe, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner) Women Writers (Angela Carter, Fay Wheldon, Emma Tennant, Penelope Lively) Other voices: Salman Rushdie (The Moor’s Last Sigh); Kazuo Ishiguro (The Remains of the Day); Ben Okri; Clive Sinclair (Blood Libels). Postmodernism: Julian Barnes; Martin Amis; Ian McEwan; Graham Swift. -

Pressreader Newspaper Titles

PRESSREADER: UK & Irish newspaper titles www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader NATIONAL NEWSPAPERS SCOTTISH NEWSPAPERS ENGLISH NEWSPAPERS inc… Daily Express (& Sunday Express) Airdrie & Coatbridge Advertiser Accrington Observer Daily Mail (& Mail on Sunday) Argyllshire Advertiser Aldershot News and Mail Daily Mirror (& Sunday Mirror) Ayrshire Post Birmingham Mail Daily Star (& Daily Star on Sunday) Blairgowrie Advertiser Bath Chronicles Daily Telegraph (& Sunday Telegraph) Campbelltown Courier Blackpool Gazette First News Dumfries & Galloway Standard Bristol Post iNewspaper East Kilbride News Crewe Chronicle Jewish Chronicle Edinburgh Evening News Evening Express Mann Jitt Weekly Galloway News Evening Telegraph Sunday Mail Hamilton Advertiser Evening Times Online Sunday People Paisley Daily Express Gloucestershire Echo Sunday Sun Perthshire Advertiser Halifax Courier The Guardian Rutherglen Reformer Huddersfield Daily Examiner The Independent (& Ind. on Sunday) Scotland on Sunday Kent Messenger Maidstone The Metro Scottish Daily Mail Kentish Express Ashford & District The Observer Scottish Daily Record Kentish Gazette Canterbury & Dist. IRISH & WELSH NEWSPAPERS inc.. Scottish Mail on Sunday Lancashire Evening Post London Bangor Mail Stirling Observer Liverpool Echo Belfast Telegraph Strathearn Herald Evening Standard Caernarfon Herald The Arran Banner Macclesfield Express Drogheda Independent The Courier & Advertiser (Angus & Mearns; Dundee; Northants Evening Telegraph Enniscorthy Guardian Perthshire; Fife editions) Ormskirk Advertiser Fingal -

A Writer's Calendar

A WRITER’S CALENDAR Compiled by J. L. Herrera for my mother and with special thanks to Rose Brown, Peter Jones, Eve Masterman, Yvonne Stadler, Marie-France Sagot, Jo Cauffman, Tom Errey and Gianni Ferrara INTRODUCTION I began the original calendar simply as a present for my mother, thinking it would be an easy matter to fill up 365 spaces. Instead it turned into an ongoing habit. Every time I did some tidying up out would flutter more grubby little notes to myself, written on the backs of envelopes, bank withdrawal forms, anything, and containing yet more names and dates. It seemed, then, a small step from filling in blank squares to letting myself run wild with the myriad little interesting snippets picked up in my hunting and adding the occasional opinion or memory. The beginning and the end were obvious enough. The trouble was the middle; the book was like a concertina — infinitely expandable. And I found, so much fun had the exercise become, that I was reluctant to say to myself, no more. Understandably, I’ve been dependent on other people’s memories and record- keeping and have learnt that even the weightiest of tomes do not always agree on such basic ‘facts’ as people’s birthdays. So my apologies for the discrepancies which may have crept in. In the meantime — Many Happy Returns! Jennie Herrera 1995 2 A Writer’s Calendar January 1st: Ouida J. D. Salinger Maria Edgeworth E. M. Forster Camara Laye Iain Crichton Smith Larry King Sembene Ousmane Jean Ure John Fuller January 2nd: Isaac Asimov Henry Kingsley Jean Little Peter Redgrove Gerhard Amanshauser * * * * * Is prolific writing good writing? Carter Brown? Barbara Cartland? Ursula Bloom? Enid Blyton? Not necessarily, but it does tend to be clear, simple, lucid, overlapping, and sometimes repetitive. -

The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 Building Unity Through State Narratives: The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941 Colin Cook University of Central Florida Part of the European History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Cook, Colin, "Building Unity Through State Narratives: The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6734. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6734 BUILDING UNITY THROUGH STATE NARRATIVES: THE EVOLVING BRITISH MEDIA DISCOURSE DURING WORLD WAR II, 1939-1941 by COLIN COOK J.D. University of Florida, 2012 B.A. University of North Florida, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2019 ABSTRACT The British media discourse evolved during the first two years of World War II, as state narratives and censorship began taking a more prominent role. I trace this shift through an examination of newspapers from three British regions during this period, including London, the Southwest, and the North. My research demonstrates that at the start of the war, the press featured early unity in support of the British war effort, with some regional variation. -

Does the Daily Paper Rule Britannia’:1 the British Press, British Public Opinion, and the End of Empire in Africa, 1957-60

The London School of Economics and Political Science ‘Does the Daily Paper rule Britannia’:1 The British press, British public opinion, and the end of empire in Africa, 1957-60 Rosalind Coffey A thesis submitted to the International History Department of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, August 2015 1 Taken from a reader’s letter to the Nyasaland Times, quoted in an article on 2 February 1960, front page (hereafter fp). All newspaper articles which follow were consulted at The British Library Newspaper Library. 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99, 969 words. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the role of British newspaper coverage of Africa in the process of decolonisation between 1957 and 1960. It considers events in the Gold Coast/Ghana, Kenya, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, South Africa, and the Belgian Congo/Congo. -

Subsidiary Undertakings Continued

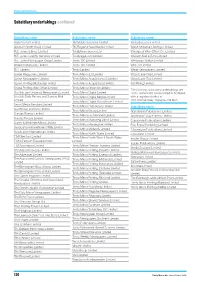

Financial Statements Subsidiary undertakings continued Subsidiary name Subsidiary name Subsidiary name Planetrecruit Limited TM Mobile Solutions Limited Websalvo.com Limited Quids-In (North West) Limited TM Regional New Media Limited Welsh Universal Holdings Limited R.E. Jones & Bros. Limited Totallyfinancial.com Ltd Welshpool Web-Offset Co. Limited R.E. Jones Graphic Services Limited Totallylegal.com Limited Western Mail & Echo Limited R.E. Jones Newspaper Group Limited Trinity 100 Limited Whitbread Walker Limited Reliant Distributors Limited Trinity 102 Limited Wire TV Limited RH1 Limited Trinity Limited Wirral Newspapers Limited Scene Magazines Limited Trinity Mirror (L I) Limited Wood Lane One Limited Scene Newspapers Limited Trinity Mirror Acquisitions (2) Limited Wood Lane Two Limited Scene Printing (Midlands) Limited Trinity Mirror Acquisitions Limited Workthing Limited Scene Printing Web Offset Limited Trinity Mirror Cheshire Limited The following subsidiary undertakings are Scottish and Universal Newspapers Limited Trinity Mirror Digital Limited 100% owned and incorporated in Scotland, Scottish Daily Record and Sunday Mail Trinity Mirror Digital Media Limited with a registered office at Limited One Central Quay, Glasgow, G3 8DA. Trinity Mirror Digital Recruitment Limited Smart Media Services Limited Trinity Mirror Distributors Limited Subsidiary name Southnews Trustees Limited Trinity Mirror Group Limited Aberdonian Publications Limited Sunday Brands Limited Trinity Mirror Huddersfield Limited Anderston Quay Printers Limited Sunday -

The Educational Backgrounds of Leading Journalists

The Educational Backgrounds of Leading Journalists June 2006 NOT FOR PUBLICATION BEFORE 00.01 HOURS THURSDAY JUNE 15TH 2006 1 Foreword by Sir Peter Lampl In a number of recent studies the Sutton Trust has highlighted the predominance of those from private schools in the country’s leading and high profile professions1. In law, we found that almost 70% of barristers in the top chambers had attended fee-paying schools, and, more worryingly, that the young partners in so called ‘magic circle’ law firms were now more likely than their equivalents of 20 years ago to have been independently-educated. In politics, we showed that one third of MPs had attended independent schools, and this rose to 42% among those holding most power in the main political parties. Now, with this study, we have found that leading news and current affairs journalists – those figures who are so central in shaping public opinion and national debate – are more likely than not to have been to independent schools which educate just 7% of the population. Of the top 100 journalists in 2006, 54% were independently educated an increase from 49% in 1986. Not only does this say something about the state of our education system, but it also raises questions about the nature of the media’s relationship with society: is it healthy that those who are most influential in determining and interpreting the news agenda have educational backgrounds that are so different to the vast majority of the population? What is clear is that an independent school education offers a tremendous boost to the life chances of young people, making it more likely that they will attain highly in school exams, attend the country’s leading universities and gain access to the highest and most prestigious professions. -

AUG21 Westfield Catalog

AUG 2021 CATALOG ORDERS DUE AUGUST ??TH $4.25 WEB ORDERS DUE AUGUST 19TH AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #75 CATWOMAN: LONELY CITY #1 HOUSE OF SLAUGHTER #1 FOR ITEMS SCHEDULED TO SHIP BEGINNING IN OCTOBER 2021 FIND MORE DESCRIPTIONS, ART AND PRODUCTS AT WWW.WESTFIELDCOMICS.COM VENOM #1 You’ve never seen a Venom like this before! Find it in Marvel Comics! ARKHAM CITY: THE ORDER OF THE WORLD #1 Residents of Arkham Asylum walk among us. Find it in DC Comics! WonderWonder WomanWoman 80th80th AnniversaryAnniversary 100-Page100-Page SuperSuper SpectacularSpectacular #1#1 (One(One Shot)Shot) STAR TREK: MIRROR WAR #1 Picard and the Enterprise take the Mirror Universe by force. Find it in IDW! JEFFIFER BLOOD #1 The suburban housewife assassin returns. Find it in Dynamite! GUNSLINGER SPAWN #1 Can anyone outdraw the Gunslinger Spawn? Find it in Image Comics! JEN BARTEL - COSTUME CELEBRATION WRAPAROUND MARVEL MEOW HC See the Marvel Universe through the eyes of Captain Marvel’s cat, Chewie. Find it in Viz! FIND THESE AND ANY OTHER CataLOG LISTINGS AT CATALOGS WESTFIELDCOMICS.COM/SECTION/CataLOG-AUG21-CataLOGS WESTFIELD CATALOG (1ST CLASS USPS) – We will be mailing all our catalogs First Class so we are not offering a separate option for this. (You must order at least once every three months to continue to receive free catalog.) PREVIEWS PACKET - Hundreds of comics and graphic novels from the best comic publishers; the coolest pop-culture merchandise; plus exclusive items available nowhere else. Each packet includes Previews, Marvel Previews, DC Currents and a Previews Customer Order Form. $3.99 [21080003] WILL MURAI - CAT STAGGS - BRUCE TIMM - Also available sent Priority Mail, separate from your regular shipment and on the same day that Previews FILM INSPIRED TELEVISION INSPIRED ANIMATION INSPIRED hits the streets - this should take approximately 2-3 days.