Barriers to Accessing Nutrition Services at Community Level

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Integrated Water Resources Management Support Project (Cofinanced by the Government of Australia and the Spanish Cooperation Fund for Technical Assistance)

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 43114 August 2014 Lao People’s Democratic Republic: National Integrated Water Resources Management Support Project (Cofinanced by the Government of Australia and the Spanish Cooperation Fund for Technical Assistance) Prepared by: IDOM Ingenieria Y Consultoria S.A. (Vizcaya, Spain) in association with Lao Consulting Group Ltd. (Vientiane, Lao PDR) For: Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Department of Water Resources Nam Ngum River Basin Committee Secretariat This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. NATIONAL INTEGRATED WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT SUPPORT PROGRAM ADB TA-7780 (LAO) PACKAGE 2: RIVER BASIN MANAGEMENT NIWRMSP - PACKAGE 2 FINAL REPORT August 2014 NIWRMSP - PACKAGE 2 FINAL REPORT National Integrated Water Resources Management Support Program ADB TA-7780 (LAO) Package 2 - River Basin Management CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IN ENGLISH ................................................................................................... S1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IN LAO ........................................................................................................... S4 1. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................... 1 2. RESOURCES ASSIGNED TO THE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE .................................................. 2 3. WORK DEVELOPED AND OBJECTIVES -

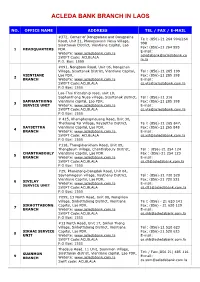

Acleda Bank Branch in Laos

ACLEDA BANK BRANCH IN LAOS NO. OFFICE NAME ADDRESS TEL / FAX / E-MAIL #372, Corner of Dongpalane and Dongpaina Te l: (856)-21 264 994/264 Road, Unit 21, Phonesavanh Neua Village, 998 Sisattanak District, Vientiane Capital, Lao Fax: (856)-21 264 995 1 HEADQUARTERS PDR. E-mail: Website: www.acledabank.com.la [email protected] SWIFT Code: ACLBLALA m.la P.O. Box: 1555 #091, Nongborn Road, Unit 06, Nongchan Village, Sisattanak District, Vientiane Capital, Tel : (856)-21 285 199 VIENTIANE Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 285 198 2 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 Lao-Thai friendship road, unit 10, Saphanthong Nuea village, Sisattanak district, Tel : (856)-21 316 SAPHANTHONG Vientiane capital, Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 285 198 3 SERVICE UNIT Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 # 415, Khamphengmeuang Road, Unit 30, Thatluang Tai Village, Xaysettha District, Te l: (856)-21 265 847, XAYSETTHA Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 265 848 4 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la, E-mail: SWIFT Code: ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 #118, Thongkhankham Road, Unit 09, Thongtoum Village, Chanthabouly District, Tel : (856)-21 254 124 CHANTHABOULY Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR Fax : (856)-21 254 123 5 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 #29, Phonetong-Dongdok Road, Unit 04, Saynamngeun village, Xaythany District, Tel : (856)-21 720 520 Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR. -

World Bank Document

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: PAD3071 Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 18.2 MILLION (US$25 MILLION EQUIVALENT) Public Disclosure Authorized TO THE LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC FOR A LAO PDR CIVIL REGISTRATION AND VITAL STATISTICS PROJECT March 9, 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Health, Nutrition, and Population Global Practice East Asia and Pacific Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. The World Bank Lao PDR Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Project (P167601) CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective January 31, 2020) Currency Unit = Lao Kip (LAK) LAK 8,884.94 = US$1 US$1.3770 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1–December 31 Regional Vice President: Victoria Kwakwa Acting Country Director: Gevorg Sargsyan Regional Director: Daniel Dulitzky Practice Manager: Daniel Dulitzky Task Team Leader(s): Samuel Lantei Mills The World Bank Lao PDR Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Project (P167601) ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS APIS Advanced Programming and Information Systems CMIS Civil Management Information System CPF Country Partnership Framework CRVS Civil Registration and Vital Statistics DA Designated Account DCM Department of Citizen Management DHIS2 District Health Information Software DOHA District Office of Home Affairs ECOP -

Vientiane Times Sexual, Reproductive Health for Vientiane Province Targets All Women to Be Ensured District Social Ills Times Reporters At- Risk Groups

th 40 Lao PDR 2/12/1975-2/12/2015 VientianeThe FirstTimes National English Language Newspaper MONDAY JULY 13, 2015 ISSUE 159 4500 kip Australia supports mining sector reform Police detail investigative Times Reporters it can be a driver for long term sustainable growth and work at NA session Australia is providing AU$ development. A streamlined 1.17 million (more than 7 process to appraise new Regarding the The spread of drugs were 288 prisoners who were billion kip) to strengthen the investments will ensure that appointment of technical throughout society was also released in Vientiane in the capacity of the Ministry of Laos can maximize the benefits experts for involvement in among the concerns NA period from 2013 to 2015, of Energy and Mines to evaluate from its natural endowment the investigation process, members raised as a query to which 55 ended up being re- development proposals in the without compromising the deputy minister said the the security body. incarcerated. mining sector, according to environmental and social victims, accused persons, Brig. Gen Kongthong Brig. Gen Konngthong the Australia Embassy to Laos. safeguards.” witnesses, investigative admitted that drugs have caused admitted the lack of vocational The Australian support will Australia’s new police, and prosecutors are an increase in the prevalence of training for them was a be used to prepare guidelines commitment built on top of a encouraged to participate in the crime and could potentially cause for the repetition of on how to undertake inter- previous AU$3 -

8Th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN

Lao People’s Democratic Republic Peace Independence Unity Prosperity 8th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2016–2020) (Officially approved at the VIIIth National Assembly’s Inaugural Session, 20–23 April 2016, Vientiane) Ministry of Planning and Investment June 2016 8th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2016–2020) (Officially approved at the VIIIth National Assembly’s Inaugural Session, 20–23 April 2016, Vientiane) Ministry of Planning and Investment June 2016 FOREWORD The 8th Five-Year National Socio-economic Development Plan (2016–2020) “8th NSEDP” is a mean to implement the resolutions of the 10th Party Conference that also emphasizes the areas from the previous plan implementation that still need to be achieved. The Plan also reflects the Socio-economic Development Strategy until 2025 and Vision 2030 with an aim to build a new foundation for graduating from LDC status by 2020 to become an upper-middle-income country by 2030. Therefore, the 8th NSEDP is an important tool central to the assurance of the national defence and development of the party’s new directions. Furthermore, the 8th NSEDP is a result of the Government’s breakthrough in mindset. It is an outcome- based plan that resulted from close research and, thus, it is constructed with the clear development outcomes and outputs corresponding to the sector and provincial development plans that should be able to ensure harmonization in the Plan performance within provided sources of funding, including a government budget, grants and loans, -

Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Draft Report: Annex A

Appendix G1 Results of Soil Analysis (Prepared by ERIC) ANNEX A RESULTS OF SOIL ANALYSIS FOR ORIGINAL PROPOSED RESTTLEMENT SITES EIA of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Draft Report: Annex A (1) Soil Properties of Four Villages for Initial Site Selection A -2 EIA of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Draft Report: Annex A A -3 EIA of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Draft Report: Annex A A -4 EIA of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Draft Report: Annex A A -5 EIA of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Draft Report: Annex A Source: Agriculture and Forestry Scientific Research Institute, Lao PDR, December 2007 A -6 EIA of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Draft Report: Annex A (2) Soil fertilities at Phukata and Pha-Aen areas, in November 2008 A -7 EIA of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Draft Report: Annex A A -8 EIA of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Draft Report: Annex A Source: Soil-Fertilizer-Environment Scientific Development Project, Kasetsart University, 2008 A -9 EIA of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Source: Soil-Fertilizer-Environment Scientific Development Project, Kasetsart University, November 2008 EIA of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project RESULTS OF SOIL ANALYSIS FOR NEW RESETTLEMENT SITE AND ORIGINAL SETTLEMENTS EIA of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Draft Report: Annex A (1) Soil Properties of Resettlement area Source: National Agriculture and Forest Research Institute, Lao PDR, August 2011 A -14 EIA of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Draft Report: Annex A Source: National Agriculture and Forest Research -

Data Collection Survey on Education Environment of Lower Secondary Schools in Lao P.D.R

Final Report: Data Collection Survey on Education Environment of Lower Secondary Schools in Lao P.D.R February, 2016 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Mohri, Architect and Associates, Inc. 1R JR 16-04 Final Report: Data Collection Survey on Education Environment of Lower Secondary Schools in Lao P.D.R February, 2016 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Mohri, Architect and Associates, Inc. Contents Chapter 1 SUMMARY OF STUDY ............................................................................................. 1-1 1-1 Context of Study .............................................................................................................. 1-1 1-2 Objective of Study ........................................................................................................... 1-1 1-3 Timeframe of Study ......................................................................................................... 1-1 1-4 Members of Study Mission (Name, Responsibility, Organization belonging to) ...... 1-2 1-5 Concerned persons consulted and/or interviewed ......................................................... 1-2 1-6 Contents of Study .......................................................................................................... 1-2 1-6-1 Local Study I ............................................................................................................ 1-2 1-6-2 Local Study II ........................................................................................................... 1-3 CHAPTER -

Thammasat Institute of Area Studies (TIARA), Thammasat University

No. 06/ 2017 Thammasat Institute of Area Studies WORKING PAPER SERIES 2017 Regional Distribution of Foreign Investment in Lao PDR Chanthida Ratanavong December, 2017 THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY PAPER NO. 09 / 2017 Thammasat Institute of Area Studies, Thammasat University Working Paper Series 2017 Regional Distribution of Foreign Investment in Lao PDR Chanthida Ratanavong Thammasat Institute of Area Studies, Thammasat University 99 Moo 18 Khlongnueng Sub District, Khlong Luang District, Pathum Thani, 12121, Thailand ©2017 by Chanthida Ratanavong. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit including © notice, is given to the source. This publication of Working Paper Series is part of Master of Arts in Asia-Pacific Studies Program, Thammasat Institute of Area Studies (TIARA), Thammasat University. The view expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the Institute. For more information, please contact Academic Support Unit, Thammasat Institute of Area Studies (TIARA), Patumthani, Thailand Telephone: +02 696 6605 Fax: + 66 2 564-2849 Email: [email protected] Language Editors: Mr Mohammad Zaidul Anwar Bin Haji Mohamad Kasim Ms. Thanyawee Chuanchuen TIARA Working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. Comments on this paper should be sent to the author of the paper, Ms. Chanthida Ratanavong, Email: [email protected] Or Academic Support Unit (ASU), Thammasat Institute of Area Studies, Thammasat University Abstract The surge of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is considered to be significant in supporting economic development in Laos, of which, most of the investments are concentrated in Vientiane. -

Page 1 of 57 LAO PEOPLE's DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC Peace

Page 1 of 57 LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC Peace Independence Democracy Unity Prosperity Prime Minister’s Office No. 301/PM Vientiane Capital, dated 12/10/2005 Decree of the Prime Minister Regarding the Implementation of The Law on Promotion of Foreign Investment - - Pursuant to the Law on the Government of the Lao PDR No. 02/NA, dated 6 May 2003; - Pursuant to the Law on Foreign Investment Promotion No. 1 1/NA, dated 22 October 2004; - Referencing the proposal of the Chairman of the Committee for Planning and Investment. Section I General Provisions Article 1. Objective This Decree is stipulated to implement the Law on Promotion of Foreign Investment in conformity with the purposes of the law in a uniform manner throughout the country on the principles, methods and measures regarding the promotion, protection, inspection, resolution of disputes, application of award policies toward good performers and imposition of measures against violators. Article 2. Legal Guarantees The State provides legal guarantees to foreign investors who are established under the Law on Promotion of Foreign Investment as follows: 2.1 administer law and regulations on the basis of equality and mutual interests; 2.2 undertake all of the State’s obligations under the laws, the international treaties in which the State is a party, agreements regarding the promotion and protection of foreign investment and the agreements that the government has signed with foreign investors; 2.3 do not interfere with the legal business operations of foreign investors. Page 2 of 57 Article 3. Capital Contribution That Is Intellectual Property The State recognizes enterprise capital contribution in the form of intellectual property. -

Independent Advisory Panel Report No. 7 on the Seventh Site Visit

Independent Advisory Panel Report Project Number: 41924-014 25 July 2016 Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project (Lao People’s Democratic Republic) Report Number 7 on the Seventh Site Visit, 15-22 May 2016 Prepared by the Independent Advisory Panel for the Asian Development Bank This report is a document of the Independent Advisory Panel. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “Terms of Use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Report Number 7 of the Independent Advisory Panel on the Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project, Lao PDR Seventh Site Visit, 15-22 May 2016 25 July 2016 1 Table of Contents Page no. List of acronyms and abbreviations 3 Introduction 4 Part 1: Independent Advisory Panel Actions 5 Part 2: Summary of IAP issues, requirements, and recommendations 8 • Summary of Resettlement Issues 8 • Summary of Social Issues 13 • Summary of Environmental Issues 18 • Summary of Biodiversity Issues 27 List of Annexes Annex 1: Resettlement Issues 33 Annex 2: Social and Indigenous Peoples’ Issues 38 Annex 3: Environmental Issues 41 Annex 4: Biodiversity Issues 48 Photos Resettlement and Social Photos 37 Environmental Photos 46 2 List -

2004 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 28, 2005

Laos Page 1 of 13 Laos Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2004 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 28, 2005 The Lao People's Democratic Republic is an authoritarian, Communist, one-party state ruled by the Lao People's Revolutionary Party (LPRP). Although the 1991 Constitution, amended in 2003, outlines a system composed of executive, legislative, and judicial branches, in practice, the LPRP continued to control governance and the choice of leaders at all levels through its constitutionally designated "leading role." In 2002, the National Assembly reelected the President and Vice President and ratified the President's selection of a prime minister and cabinet. The judiciary was subject to executive influence. The Ministry of Public Security (MoPS) maintains internal security, but shares the function of state control with the Ministry of Defense's security forces and with party and popular fronts (broad-based organizations controlled by the LPRP). The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, with MoPS support, is responsible for oversight of foreigners. The MoPS includes local police, immigration police, security police (including border police), and other armed police units. Communication police are responsible for monitoring telephone and electronic communications. The armed forces are responsible for external security, but also have domestic security responsibilities that include counterterrorism and counterinsurgency activities and control of an extensive system of village militias. The LPRP, and not the Government, exercised direct control of the security forces. This control was generally effective, but individuals and units within the security forces on occasion acted outside the LPRP's authority. Some members of the security forces committed serious human rights abuses. -

41924-014: Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project

Resettlement and Ethnic Development Plan Project Number: 41924 June 2014 Document Stage: Final Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project (Lao People’s Democratic Republic) Main Report Prepared by Nam Ngiep 1 Power Company Ltd. for the Asian Development Bank The final report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “Terms of Use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Resettlement and Ethnic Development Plan for Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project Updated Version, June 2014 REDP of The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project List of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. VI LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................................... XXIV LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................................................... XXVIII ABBREVIATIONS .........................................................................................................................................