Profile on Environmental and Social Considerations in Lao P.D.R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey of Wild Animals in Market -Tuensang, Nagaland

Mongabay.com Open Access Journal - Tropical Conservation Science Vol.6 (2):241-253, 2013 Research Article Wildlife exploitation: a market survey in Nagaland, North-eastern India Subramanian Bhupathy1*, Selvaraj Ramesh Kumar1, Palanisamy Thirumalainathan1, Joothi Paramanandham1, and Chang Lemba2 1Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History Anaikatti (Post), Coimbatore- 641 108, Tamil Nadu, India 2C/o Moa Chang, Youth Secretary, Near Chang Baptist, Lashong, Thangnyen, Mission Compound, Tuensang, Nagaland, India *Corresponding Author ([email protected]) Abstract With growing human population, increased accessibility to remote forests and adoption of modern tools, hunting has become a severe global problem, particularly in Nagaland, a Northeast Indian state. While Indian wildlife laws prohibit hunting of virtually all large wild animals, in several parts of North-eastern parts of India that are dominated by indigenous tribal communities, these laws have largely been ineffective due to cultural traditions of hunting for meat, perceived medicinal and ritual value, and the community ownership of the forests. We report the quantity of wild animals sold at Tuensang town of Nagaland, based on weekly samples drawn from May 2009 to April 2010. Interviews were held with vendors on the availability of wild animals in forests belonging to them and methods used for hunting. The tribes of Chang, Yimchunger, Khiemungan, and Sangtam are involved in collection/ hunting and selling of animals in Tuensang. In addition to molluscs and amphibians, 1,870 birds (35 species) and 512 mammals (8 species) were found in the samples. We estimated that annually 13,067 birds and 3,567 mammals were sold in Tuensang market alone, which fetched about Indian Rupees ( ) 18.5 lakhs/ year. -

Spatial Distribution and Historical Dynamics of Threatened Conifers of the Dalat Plateau, Vietnam

SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION AND HISTORICAL DYNAMICS OF THREATENED CONIFERS OF THE DALAT PLATEAU, VIETNAM A thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By TRANG THI THU TRAN Dr. C. Mark Cowell, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2011 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION AND HISTORICAL DYNAMICS OF THREATENED CONIFERS OF THE DALAT PLATEAU, VIETNAM Presented by Trang Thi Thu Tran A candidate for the degree of Master of Arts of Geography And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor C. Mark Cowell Professor Cuizhen (Susan) Wang Professor Mark Morgan ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research project would not have been possible without the support of many people. The author wishes to express gratitude to her supervisor, Prof. Dr. Mark Cowell who was abundantly helpful and offered invaluable assistance, support, and guidance. My heartfelt thanks also go to the members of supervisory committees, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Cuizhen (Susan) Wang and Prof. Mark Morgan without their knowledge and assistance this study would not have been successful. I also wish to thank the staff of the Vietnam Initiatives Group, particularly to Prof. Joseph Hobbs, Prof. Jerry Nelson, and Sang S. Kim for their encouragement and support through the duration of my studies. I also extend thanks to the Conservation Leadership Programme (aka BP Conservation Programme) and Rufford Small Grands for their financial support for the field work. Deepest gratitude is also due to Sub-Institute of Ecology Resources and Environmental Studies (SIERES) of the Institute of Tropical Biology (ITB) Vietnam, particularly to Prof. -

North-South Expressway Master Plan Final Report

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT, VIETNAM THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN VIETNAM (VITRANSS 2) North-South Expressway Master Plan Final Report May 2010 ALMEC CORPORATION ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO. LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO. LTD. JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT, VIETNAM THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN VIETNAM (VITRANSS 2) North-South Expressway Master Plan Final Report May 2010 ALMEC CORPORATION ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO. LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO. LTD. Exchange Rate Used in the Report USD 1 = JPY 110 = VND 17,000 (Average Rate in 2008) PREFACE In response to the request from the Government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, the Government of Japan decided to conduct the Comprehensive Study on the Sustainable Development of Transport System in Vietnam (VITRANSS2) and entrusted the program to the Japan International cooperation Agency (JICA) JICA dispatched a team to Vietnam between November 2007 and May 2010, which was headed by Mr. IWATA Shizuo of ALMEC Corporation and consisted of ALMEC Corporation, Oriental Consultants Co., Ltd., and Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. In the cooperation with the Vietnamese Counterpart Team, the JICA Study Team conducted the study. It also held a series of discussions with the relevant officials of the Government of Vietnam. Upon returning to Japan, the Team duly finalized the study and delivered this report. I hope that this report will contribute to the sustainable development of transport system and Vietnam and to the enhancement of friendly relations between the two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials of the Government of Vietnam for their close cooperation. -

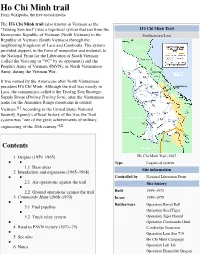

Ho Chi Minh Trail from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Ho Chi Minh trail From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Hồ Chí Minh trail (also known in Vietnam as the "Trường Sơn trail") was a logistical system that ran from the Hồ Chí Minh Trail Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) to the Southeastern Laos Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) through the neighboring kingdoms of Laos and Cambodia. The system provided support, in the form of manpower and materiel, to the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (called the Vietcong or "VC" by its opponents) and the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN), or North Vietnamese Army, during the Vietnam War. It was named by the Americans after North Vietnamese president Hồ Chí Minh. Although the trail was mostly in Laos, the communists called it the Trường Sơn Strategic Supply Route (Đường Trường Sơn), after the Vietnamese name for the Annamite Range mountains in central Vietnam.[1] According to the United States National Security Agency's official history of the war, the Trail system was "one of the great achievements of military engineering of the 20th century."[2] Contents 1 Origins (1959–1965) Ho Chi Minh Trail, 1967 Type Logistical system 1.1 Base areas Site information 2 Interdiction and expansion (1965–1968) Controlled by National Liberation Front 2.1 Air operations against the trail Site history 2.2 Ground operations against the trail Built 1959–1975 3 Commando Hunt (1968–1970) In use 1959–1975 Battles/wars Operation Barrel Roll 3.1 Fuel pipeline Operation Steel Tiger 3.2 Truck relay system Operation Tiger Hound Operation Commando Hunt 4 Road to PAVN victory (1971–75) Cambodian Incursion Operation Lam Son 719 5 See also Ho Chi Minh Campaign 6 Notes Operation Left Jab Operation Honorable Dragon Operation Diamond Arrow 7 Sources Project Copper Operation Phiboonpol Operation Sayasila Origins (1959–1965) Operation Bedrock Operation Thao La Parts of what became the trail had existed for centuries as Operation Black Lion primitive footpaths that facilitated trade. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Projecting Forest Tree Distributions and Adaptation to Climate Change in Northern Thailand

Journal of Ecology and Natural Environment Vol. 1(3), pp. 055-063, June, 2009 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JENE © 2009 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Projecting forest tree distributions and adaptation to climate change in northern Thailand Yongyut Trisurat1* Rob Alkemade2 and Eric Arets2 1Faculty of Forestry, Kasetsart University Bangkok 10900, Thailand 2The Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency P.O. Box 303, 3720 AH Bilthoven, Netherlands. Accepted 18 May, 2009 Climate change is a global threat to biodiversity because it has the potential to cause significant impacts on the distribution of species and the composition of habitats. The objective of this research is to evaluate the consequence of climate change in distribution of forest tree species, both deciduous and evergreen species. We extracted the HadCM3 A2 climate change scenario (regionally-oriented economic development) for the year 2050 in northern Thailand. A machine learning algorithm based on maximum entropy theory (MAXENT) was employed to generate ecological niche models of forest plants. Six evergreen species and 16 deciduous species were selected using the criteria developed by the Asia Pacific Forest Genetic Resources Programme (APFORGEN) for genetic resources conservation and management. Species occurrences were obtained from the Department of National Park, Wildlife and Plant Conservation. The accuracy of each ecological niche model was assessed using the area under curve of a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The results show that the total extent of occurrence of all selected plant species is not substantially different between current and predicted climate change conditions. However, their spatial configuration and turnover rate are high, especially evergreen tree species. -

2019 FAO/WFP Crop and Food Security Assessment Mission to the Lao People's Democratic Republic

ISSN 2707-2479 SPECIAL REPORT 2019 FAO/WFP CROP AND FOOD SECURITY ASSESSMENT MISSION (CFSAM) TO THE LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC 9 April 2020 SPECIAL REPORT 2019 FAO/WFP CROP AND FOOD SECURITY ASSESSMENT MISSION (CFSAM) TO THE LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC 9 April 2020 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2020 Required citation: FAO. 2020. Special Report - 2019 FAO/WFP Crop and Food Security Assessment Mission to the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca8392en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISSN 2707-2479 [Print] ISSN 2707-2487 [Online] ISBN 978-92-5-132344-1 [FAO] © FAO, 2020 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode). -

Toskar Newsletter

TOSKAR NEWSLETTER A Quarterly Newsletter of the Orchid Society of Karnataka (TOSKAR) Vol. No. 4; Issue: ii; 2017 THE ORCHID SOCIETY OF KARNATAKA www.toskar.org ● [email protected] From the Editor’s Desk TOSKAR NEWSLETTER 21st June 2017 The much-awaited monsoon has set in and it is a sight to see EDITORIAL BOARD shiny green and happy leaves and waiting to put forth their best (Vide Circular No. TOSKAR/2016 Dated 20th May 2016) growth and amazing flowers. Orchids in tropics love the monsoon weather and respond with a luxurious growth and it is also time for us (hobbyists) to ensure that our orchids are fed well so that Chairman plants put up good vegetative growth. But do take care of your Dr. Sadananda Hegde plants especially if you are growing them in pots and exposed to continuous rains, you may have problems! it is alright for mounted plants. In addition, all of us have faced problems with Members snails and slugs, watch out for these as they could be devastating. Mr. S. G. Ramakumar Take adequate precautions with regard to onset of fungal and Mr. Sriram Kumar bacterial diseases as the moisture and warmth is ideal for their multiplication. This is also time for division or for propagation if Editor the plants have flowered. Dr. K. S. Shashidhar Many of our members are growing some wonderful species and hybrids in Bangalore conditions and their apt care and culture is Associate Editor seen by the fantastic blooms. Here I always wanted some of them Mr. Ravee Bhat to share their finer points or tips for care with other growers. -

Dendrobium Anosmum

CÔNG NGHỆ GEN PHÂN TÍCH SỰ ĐA DẠNG DI TRUYỀN GIỮA CÁC GIỐNG LAN GIẢ HẠC (Dendrobium anosmum) DỰA TRÊN CHỈ THỊ PHÂN TỬ SSR Huỳnh Hữu Đức*, Nguyễn Trường Giang, Nguyễn Hoàng Cẩm Tú, Dương Hoa Xô Trung tâm Công nghệ Sinh học Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh TÓM TẮT Lan Giả hạc (Dendrobium anosmum) là loài lan có giá trị kinh tế cao, có sự phân bố rộng và thích nghi với nhiều vùng sinh thái khác nhau ở nước ta. Nhằm mục tiêu đánh giá đa dạng di truyền giữa các nguồn gen từ các vùng sinh thái khác nhau phục vụ bảo tồn và lai tạo giống mới, 20 mẫu giống lan Giả hạc có nguồn gốc khác nhau được thu thập và đánh giá bằng chỉ thị phân tử SSR. Kết quả phân tích và đánh giá di truyền của các mẫu giống lan này dựa trên 18 SSR cho thấy tổng số alen thu được là 79, trong đó tổng số alen đa hình là 77 với giá trị trung bình 4,28 alen/loci. Kết quả phân tích 18 SSR cho 20 mẫu lan thu thập cho thấy có sự phân nhóm di truyền thành 7 nhóm chính với khoảng cách di truyền là 0,172. Trong đó, tính đa hình giữa các mẫu giống lan Giả hạc đạt từ 0,237 đến 0,992 với trung bình là 0,699. Các kết quả trên cho thấy rằng các mẫu giống lan Giả hạc có nguồn gốc từ các vùng sinh thái khác nhau có sự đa dạng di truyền nhất định, đây là nguồn gen có giá trị cần được bảo tồn và sử dụng cho mục tiêu lai tạo giống trong tương lai. -

Caesalpinioideae, Fabaceae) Reveals No Significant Past 4 Fragmentation of Their Distribution Ranges

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/730911; this version posted August 9, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 TITLE : 2 Population genomics of the widespread African savannah trees Afzelia africana and 3 Afzelia quanzensis (Caesalpinioideae, Fabaceae) reveals no significant past 4 fragmentation of their distribution ranges 5 AUTHORS : 6 7 Armel S.L. Donkpegan1,2,3*, Rosalía Piñeiro4,5, Myriam Heuertz6, Jérôme Duminil2,7,8, Kasso 8 Daïnou 1,2,9, Jean-Louis Doucet1 and Olivier J. Hardy2 9 10 11 AFFILIATIONS : 12 13 14 1 University of Liège, Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech, Management of Forest Resources, Tropical 15 Forestry, TERRA, 2 Passage des Déportés, B-5030 Gembloux, Belgium 16 17 2 Evolutionary Biology and Ecology Unit, CP 160/12, Faculté des Sciences, Université Libre de 18 Bruxelles, 50 avenue F. D. Roosevelt, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium 19 20 3 UMR 1332 BFP, INRA, Université de Bordeaux, F-33140, Villenave d’Ornon, France 21 22 4 University of Exeter, Geography, College of Life and Environmental Sciences, Stocker road, 23 EX44QD, Exeter, UK 24 25 5 Evolutionary Genomics, Centre for Geogenetics - Natural History Museum of Denmark, Øster 26 Voldgade 5-7, 1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark 27 28 6 Biogeco, INRA, Univ. Bordeaux, 69 route d’Arcachon, F-33610 Cestas, France 29 30 7 DIADE, IRD, Univ Montpellier, 911 Avenue Agropolis, BP 64501, 34394 Montpellier, France. -

Distribution of Vascular Epiphytes Along a Tropical Elevational Gradient: Disentangling Abiotic and Biotic Determinants

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Distribution of vascular epiphytes along a tropical elevational gradient: disentangling abiotic and Received: 23 June 2015 Accepted: 16 December 2015 biotic determinants Published: 22 January 2016 Yi Ding1, Guangfu Liu2, Runguo Zang1, Jian Zhang3,4, Xinghui Lu1 & Jihong Huang1 Epiphytic vascular plants are common species in humid tropical forests. Epiphytes are influenced by abiotic and biotic variables, but little is known about the relative importance of direct and indirect effects on epiphyte distribution. We surveyed 70 transects (10 m × 50 m) along an elevation gradient (180 m–1521 m) and sampled all vascular epiphytes and trees in a typical tropical forest on Hainan Island, south China. The direct and indirect effects of abiotic factors (climatic and edaphic) and tree community characteristics on epiphytes species diversity were examined. The abundance and richness of vascular epiphytes generally showed a unimodal curve with elevation and reached maximum value at ca. 1300 m. The species composition in transects from high elevation (above 1200 m) showed a more similar assemblage. Climate explained the most variation in epiphytes species diversity followed by tree community characteristics and soil features. Overall, climate (relative humidity) and tree community characteristics (tree size represented by basal area) had the strongest direct effects on epiphyte diversity while soil variables (soil water content and available phosphorus) mainly had indirect effects. Our study suggests that air humidity is the most important abiotic while stand basal area is the most important biotic determinants of epiphyte diversity along the tropical elevational gradient. Understanding the mechanisms of species distributions at different spatial scales remains a central question of community ecology and biogeography1. -

Phytogeographic Review of Vietnam and Adjacent Areas of Eastern Indochina L

KOMAROVIA (2003) 3: 1–83 Saint Petersburg Phytogeographic review of Vietnam and adjacent areas of Eastern Indochina L. V. Averyanov, Phan Ke Loc, Nguyen Tien Hiep, D. K. Harder Leonid V. Averyanov, Herbarium, Komarov Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Prof. Popov str. 2, Saint Petersburg 197376, Russia E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Phan Ke Loc, Department of Botany, Viet Nam National University, Hanoi, Viet Nam. E-mail: [email protected] Nguyen Tien Hiep, Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources of the National Centre for Natural Sciences and Technology of Viet Nam, Nghia Do, Cau Giay, Hanoi, Viet Nam. E-mail: [email protected] Dan K. Harder, Arboretum, University of California Santa Cruz, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, California 95064, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] The main phytogeographic regions within the eastern part of the Indochinese Peninsula are delimited on the basis of analysis of recent literature on geology, geomorphology and climatology of the region, as well as numerous recent literature information on phytogeography, flora and vegetation. The following six phytogeographic regions (at the rank of floristic province) are distinguished and outlined within eastern Indochina: Sikang-Yunnan Province, South Chinese Province, North Indochinese Province, Central Annamese Province, South Annamese Province and South Indochinese Province. Short descriptions of these floristic units are given along with analysis of their floristic relationships. Special floristic analysis and consideration are given to the Orchidaceae as the largest well-studied representative of the Indochinese flora. 1. Background The Socialist Republic of Vietnam, comprising the largest area in the eastern part of the Indochinese Peninsula, is situated along the southeastern margin of the Peninsula.