Fields of Vision: the Arts in Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater

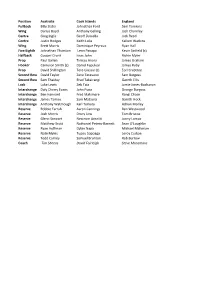

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater Johnathan Ford Sam Tomkins Wing Darius Boyd Anthony Gelling Josh Charnley Centre Greg Inglis Geoff Daniella Jack Reed Centre Justin Hodges Keith Lulia Kallum Watkins Wing Brett Morris Dominique Peyroux Ryan Hall Five Eighth Johnathan Thurston Leon Panapa Kevin Sinfield (c) Halfback Cooper Cronk Issac John Richie Myler Prop Paul Gallen Tinirau Arona James Graham Hooker Cameron Smith (c) Daniel Fepuleai James Roby Prop David Shillington Tere Glassie (c) Eorl Crabtree Second Row David Taylor Zane Tetevano Sam Burgess Second Row Sam Thaiday Brad Takairangi Gareth Ellis Lock Luke Lewis Zeb Taia Jamie Jones-Buchanan Interchange Daly Cherry Evans John Puna George Burgess Interchange Ben Hannant Fred Makimare Rangi Chase Interchange James Tamou Sam Mataora Gareth Hock Interchange Anthony Watmough Karl Temata Adrian Morley Reserve Robbie Farrah Aaron Cannings Ben Westwood Reserve Josh Morris Drury Low Tom Briscoe Reserve Glenn Stewart Neccrom Areaiiti Jonny Lomax Reserve Matthew Scott Nathaniel Peteru-Barnett Sean O'Loughlin Reserve Ryan Hoffman Dylan Napa Michael Mcllorum Reserve Nate Myles Tupou Sopoaga Leroy Cudjoe Reserve Todd Carney Samuel Brunton Rob Burrow Coach Tim Sheens David Fairleigh Steve Mcnamara Fiji France Ireland Italy Jarryd Hayne Tony Gigot Greg McNally James Tedesco Lote Tuqiri Cyril Stacul John O’Donnell Anthony Minichello (c) Daryl Millard Clement Soubeyras Stuart Littler Dom Brunetta Wes Naiqama (c) Mathias Pala Joshua Toole Christophe Calegari Sisa Waqa Vincent -

Your FREE Magazine from Your Local NHS We Meet... Kevin Sinfield Volunteering Opportunities Care for Dementia Competitions and Quizzes Plus

EngageIssue One: October 2014 Your FREE magazine from your local NHS We meet... Kevin Sinfield Volunteering opportunities Care for dementia Competitions and quizzes Plus... lots more! Start as we mean to go on? Well here we are breaking new ground as we launch our first ever community Contents magazine, we hope you 03 Get involved with 10 Making Leeds share this with friends your local NHS child friendly across the city. To help us There’s lots of ways you can Find out more about the Breeze ‘try’ to ‘tackle’ our first game help your local NHS so that programme and a new app we can develop the best tackling the perils of sexting nerves (ok no more rugby possible services metaphors!) we interviewed 11 Cinnamon doesn’t 04 Volunteering makes a quite make the grade Kevin Sinfield, captain of difference at Hollybush Find out why we have done Leeds Rhinos Rugby League 05 Breaking new ground a cinnamon review! club. He tells us about how in patient involvement 12 Spotlight on… Armley he prepares for a game, A first for the CCG… There’s more to Armley than what got him playing in find out why you might think the first place and why he 06 Kevin Sinfield interview 13 News in brief We met up with ‘Sinny’ and Catch up on the latest local never lets asthma get in the talked about rugby, asthma updates you might have missed way of being a world beater. and life as a captain 14 Competition and quizzes So what else have we got in 08 A day in the life of… Win a signed Leeds Rhinos shirt Want to know what life is like 15 Gardening guru our first edition… some great as a pharmacist in the medicines Our resident gardening expert optimisation team gardening tips, a review of takes a break from the outdoors an app protecting children 09 Caring for someone to bring you some top tips with dementia from the perils of sexting 16 Sports round up Barbara tells us more about and a special mention to Local football club celebrates her experience as one of the a special birthday local football club Wortley city’s 70,000 unpaid carers FC for reaching their 40th anniversary. -

CAPTAIN JONES LOOKING FORWARD to EXCITING TIMES Ew Yorkshire Carnegie “The Biggest Focus This Year Is Captain Chris Jones Says for Us to Play As a Team

ISSUE 01 | YORKSHIRE CARNEGIE vs JERSEY | SUNDAY 6TH SEPTEMBER, 2015 WHAT'S INSIDE CARNEGIE 2347 Get up to Catch up Get your fi rst Introducing date with the with all the look at the this club's facts, goings-on at Yorkshire afternoon's TIMES fi gures & Headingley Carnegie visitors, THE OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER OF YORKSHIRE CARNEGIE fi xtures Carnegie squad Jersey Rugby CAPTAIN JONES LOOKING FORWARD TO EXCITING TIMES ew Yorkshire Carnegie “The biggest focus this year is captain Chris Jones says for us to play as a team. People N the whole squad are may look at that and think it excited about the new Greene is a bit of a cliché in a team King IPA Championship as they sport but it is something that prepare to kick off the campaign can make a huge difference today against Jersey. but that needs constantly to be Jones has taken over from worked at. We can not rely on Ryan Burrows this season and individuals to step up and save believes the squad are in the us when things are not going best possible shape to mount well. That collective spirit was a promotion challenge. He shown in our pre-season games commented: “It is exciting now when things did begin to move that we are fi nally at the start away from us that our scrum in of the season. It is hard in pre- particular gave us a platform to season because you are getting restore control in the game. The fl ogged day in, day out but front rowers have really stepped then you get to the fi rst game up this summer with Rob of the season and you begin to O’Donnell coming to add some appreciate what all that hard competition and Phil Nilsen work is for. -

Internet Only Auction - Signed Memorabilia, Photographs & Covers Friday 25 November 2011 09:00

Internet Only Auction - Signed Memorabilia, Photographs & Covers Friday 25 November 2011 09:00 Chaucer Auctions Webster House 24 Jesmond Street Folkestone CT19 5QW Chaucer Auctions (Internet Only Auction - Signed Memorabilia, Photographs & Covers) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Astronaut signed collection 10 x 8 colour photos signed by Torchwood three colour signed photos inc. Burn Gorman & Victor Gorbatko, Ed Gibson, Helen Sharman signed to rear of Gareth David Lloyd. Good Condition colour portrait postcard. Good Condition Estimate: £10.00 - £15.00 Estimate: £10.00 - £15.00 Lot: 2 Lot: 12 Cricket three 6 x 4 action photos signed by Michael Vaughan, Collection of 16 New Zealand Royal Air Force covers Graeme Swann & Stuart Broad. Good Condition commemorating operation Ice Cube in 1974 all flying and many Estimate: £10.00 - £15.00 signed by the pilots who flew the covers. Good Condition Estimate: £8.00 - £12.00 Lot: 3 Cricket three colour action photos signed by Michael Vaughan, Lot: 13 Graeme Swann & Stuart Broad. Good Condition Aviation and flight collection in red cover album containing a Estimate: £10.00 - £15.00 proximally 40 assorted fly covers including many unusual ones for example 25th anniversary of the Berlin airlift, meteor flown flying display cover, Diamond Jubilee Channel crossing signed 1973 Chilean army expedition cover signed, Wellington cover Lot: 4 signed by Air Commodore Mickey Mount DSO DFC, Vickers Dragons Den four colour photos signed by Theo, Duncan, Vimy flown covers, BOAC VC10, four early Air Display multiple Peter & Debra. Good Condition signed covers, Canadian RAF covers, Lancaster Association Estimate: £10.00 - £15.00 sinking of the Tirpitz, multiple signed Mosquito Aircraft Museum cover. -

Coventry Legends

Steve Phelps 29 MINUTES FROM WEMBLEY COVENTRY LEGENDS The Inside Story of Coventry City’s 1980/81 Season Steve Phelps Contents Acknowledgements . 7 Introduction . 9 The Cast . 11 Welcome to Coventry City Football Club . 13 Pre-season 1980/81 . 40 The Goal That Never Was . 50 Farewell to ‘Hutch’ . 71 From the Abbey to the Connexion . 84 Bodak’s The Name, Goals Are My Game . 98 And They All Run to Little Danny Thomas . 110 Seats For All At Highfield Road . 149 Just How Good Could That Team Have Been? . 161 Welcome to Coventry City Football Club HE 1970s established Coventry City in Division One of the Football League . Promoted to the top flight in 1967, Tthey were managed by Jimmy Hill who led the ‘sky blue revolution’ and took the club from Division Three to Division One upon his arrival in 1961 . Hill’s sudden departure to London Weekend Television prior to the opening game at Burnley saw the appointment of Noel Cantwell as manager . The Sky Blues finished one place above the relegation zone in 1967/68 and 1968/69 before an unbelievable sixth place in 1969/70 ensured qualification for the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup . Tenth place in 1970/71 continued the progress until March 1972 when, with the side 18th in the division, Cantwell was sacked and chief scout Bob Dennison took over as caretaker until the season’s end . Jimmy Hill would return as managing director in 1975 and combined the role with presenting Match of the Day on BBC1 before, as a major shareholder, taking on the chairman’s role in the summer of 1980 . -

Annual Report

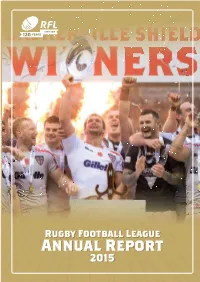

2015 RFL ANNUAL REPORT 2015 RFL ANNUAL RugbyRugby FootballFootball LeagueLeague AnnualAnnual ReportReport 20152015 RFL ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2015 CEO’s Review 4-6 Further Education 29 Chairman’s View 7 Schools 30-31 Board of Directors 8-9 Rugby League Cares 32-34 120 Years 10 Play Touch RL 35 Wembley Statue 11 Concussion 36 Magic Weekend 12 Cardiac Screening 37 World Club Series 13 Player Welfare 38-40 England Review 14-15 Hall of Fame 42 THE RUGBY Domestic Season Review 16-23 Safeguarding 43 FOOTBALL LEAGUE Events Review 24-25 RLEF Review 44-45 Red Hall, Red Hall Lane, Leeds, LS17 8NB Commercial Review 26-27 Operational Plan 46-47 T: 0844 477 7113 Higher Education 28 Financial Review 48-50 www.therfl .co.uk 3 The protocol on concussion was also CHIEF EXECUTIVE updated. Players suffering a suspected concussion during a game now have to undergo a proper assessment off the fi eld, with a free interchange allowed. The sport also mourned the passing OFFICER’S REPORT of Super League Match Offi cial Chris The year 2015 represented the 120th anniversary of the This secured their second trophy of the season, having already Leatherbarrow, a talented individual who creation of the sport of Rugby League and as was fi tting for this lifted the Ladbrokes Challenge Cup with a comprehensive win over tragically died at such a young age. momentous occasion, a number of celebratory events took place Hull Kingston Rovers at Wembley. A memorable treble beckoned to appropriately acknowledge this milestone. One of the biggest and it proved to be a nailbiting climax to the season when they VIEWERS AND was the Founders Walk, a 120-mile trek which took in each of the faced Wigan Warriors in the First Utility Grand Final. -

Award Winners

- PE AWARDS EVENING- Year 7 Boys Performer of the Year - Tom Potts Year 7 Team of the Year - Girls' Athletics Year 7 Girls Performer of the Year - Kate Leddy Year 8 Team of the Year - Girls' Netball Year 8 Boys Performer of the Year - Adam Jones Year 9 Team of the Year - Basketball Year 8 Girls Performer of the Year - Yasmin Roebuck Year 10 Team of the Year - Boys’ Athletics Track his year the Saddleworth School PE department, of playing professional football. Harry is a true inspiration welcomed students from all year groups to the to young people and aspiring footballers as he has always T Year 9 Boys Performer of the Year - Greg Simister Commitment to Extra-Curricular - Isabelle Ward conducted himself with integrity and respect for others and inaugural Saddleworth School Sports Awards Evening. This was an amazing opportunity for the staff to thank always goes the extra mile to help out anyone he can and in Year 9 Girls Performer of the Year - Daisy Shepardson. Commendation for Effort - James Stallard everyone for their amazing contributions to school sport, any capacity. extra- curricular PE, Pupil leadership and academic PE. The Year 10 Boys Performer of the Year - Jonny Marston Commendation for Achievement - Catherine Stott event was opened with the very talented Mr Beckwith and Issy is currently part of the Manchester City Ladies set the school band playing a variety of inspiring songs. up, having been taken into their development set up after Year 10 Girls Performer of the Year - Isobel Hallam Commendation for Progress - Laura Barlow impressive performances for Sheffield Ladies and The PE department has had a truly amazing 12 months helping them to a Women’s Premier League, league and cup celebrating a large number of successes on and off the double. -

The Bob Stokoe Story (Hardback) ^ Ebook ~ D3PAHNFMN6

Northern and Proud: The Bob Stokoe Story (Hardback) ^ eBook ~ D3PAHNFMN6 North ern and Proud: Th e Bob Stokoe Story (Hardback) By Paul Harrison Pitch Publishing Ltd, United Kingdom, 2009. Hardback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. Bob Stokoe created one of the greatest moments in football history when his Second Division Sunderland side defeated the might of Leeds United in the 1973 FA Cup final. When the final whistle shrilled out across Wembley and most of the football world celebrated his side s incredible triumph against the odds, Stokoe danced across the turf, arms outstretched to rejoice with his players. That moment has been immortalised in the both the TV footage and a statue outside Sunderland s new home, the Stadium of Light. Stokoe was all the more remarkable because he had managed to cross the divide in the north east. As a player he had been a member of Newcastle s 1950s FA Cup winning teams as a centre-half seemingly hewn out of granite who took no prisoners as he protected the likes of Jackie Milburn, Bobby Mitchell, George Robledo and Len White. During a forty-year career in the game, which took in spells with Hartlepool United, Bury and managerial stints with Charlton Athletic, Carlisle United, Blackpool and Rochdale, Stokoe locked swords on the pitch with Brian Clough, over the... READ ONLINE [ 5.55 MB ] Reviews This publication is definitely not eortless to get going on looking at but really exciting to read through. It really is rally intriguing throgh looking at time period. Its been written in an remarkably straightforward way which is just soon aer i finished reading through this book where basically altered me, change the way i think. -

2020 Annual 1 What’S Inside Welcome

2020 Annual 1 What’s Inside Welcome. Welcome 2 Andrew Ferguson Rugby League & the ‘Spanish Flu’ 3 Nick Tedeschi Making the Trains Run on Time 4 Hello and welcome to the first ever Rugby League Suzie Ferguson Being a rugby league fan in lockdown 5 Project Annual. Yearbooks of the past have always Will Evans Let’s Gone Warriors 6-7 been a physical book detailing every minutiae of the RL Eye Test How the game changed statisically 8-10 particular season, packed full of great memories, Jason Oliver & Oscar Pannifex statistics and history. Take the Repeat Set: NRL Grand Final 11-13 Ben Darwin Governance vs Performance 14-15 This yearbook is a twist on the usual yearbook as it 2020 NRL Season & Grand Final 16-18 not only looks at the Rugby League season of 2020, 2020 State of Origin series 19-21 but most importantly, it celebrates the immensely NRL Club Reviews Brisbane 22-23 brilliant, far-reaching and diverse community of Canberra 24-25 Canterbury-Bankstown 26-27 independent Rugby League content creators, from Cronulla-Sutherland 28-29 Australia, New Zealand, England and even Canada! Gold Coast 30-31 Manly-Warringah 32-33 This is not about one individual website, writer Melbourne 34-35 or creator. This is about a community of fans who Newcastle 36-37 are uniquely skilled and talented and who all add North Queensland 38-39 to the match day experience for supporters of Parramatta 40-41 Rugby League around the world, in ways that the Penrith 42-43 mainstream media simply cannot. -

Handbook 2010.Indd

ENGLISH SCHOOLS' RUGBY LEAGUE HANDBOOK 2010/11 With the support of the RFL Sponsored by NASUWT www.carnegiechampionschools.co.uk 2 CONTENTS Chairman’s Foreword 4 Officials of English Schools’ Rugby League 5 ESRL & Its Historic Roots 6 Past Officials 8 Constitution 10 Competition Rules 12 Annual Report 14 L’Entente Cordiale 17 ESRL v Australia 26 Inter-town Competitions & ESRL Trophies 28 Champion School Competitions 32 Yorkshire Schools Rugby League 37 North West Counties Schools Rugby League 39 Timelines - Champion Schools Tournament 2010/11 41 Champion Schools Tournament 2010/11 42 Champion Schools Competition Conveners 44 RFL Development Contacts 45 3 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD t has, once again, been a very successful Iyear for English Schools’ Rugby League, with an increase in the number of schools playing rugby league in many new areas as well as the traditional ones. The number of girls playing has shown a marked increase. The Carnegie Champion Schools tournament once again exceeded the expectation of everyone, indicating what a superb tournament it is. The finals - held at the new venue of Hillingdon Sports and Leisure Centre - were wonderful and we were lucky enough to have good weather. The event went like clockwork, due to the great number of volunteers who knew their tasks and went about them with confidence. I would like to thank all the volunteers, the RAF staff, especially Damian Clayton, the RFL staff, Carnegie staff, my elcome to the 2009/10 English Schools colleagues in ESRL and Barrie McDermott, WRugby League handbook. Terry O’Connor and all our presenters who Schools Rugby League continues to play an always give their time so willingly. -

Bulletin 61.Indd

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE RFL | ISSUE 61 RRRRIIISISSSIIININNNGGGG T TTTOOOO TTTTHHHHEEEE T TTTOOOOPPPP QUE STION TIME GO ING GLOBAL RUGBY LEAGUE BULLETIN October 2009 CONTENTS 5 Media Matters SEE THE SUPER POWERS OF INTERNATIONAL RUGBY 6 Grand Designs North Eastern LEAGUE CLASH THIS OCTOBER AND NOVEMBER Promise 8 12 Passing On Their Experience 14 Higgins At The Helm 15 Super Human! 18 Taking Aim 19 Euro-vision Rising To The Top 10 20 Promising Signs 24 Helping The Grass Roots Thrive 26 Learning With The Skolars 27 Making The Grade One Hell Of A WeekendQuestion 28 Tales From Wembley PgTime 16 & 17 16 Friday 23rd October Saturday 31st October Saturday 14th November Published by the Rugby League Services Department of the RFL. ENGLAND V FRANCE ENGLAND V AUSTRALIA The RFL, The Zone, St Andrews Road, Huddersfield, HD1 6PT. CubsGoing To Lions KEEPMOAT STADIUM, DONCASTER DW STADIUM, WIGAN Tel - 01484 448000 | Fax - 01484 545582, Global 22 Saturday 24th October Saturday 7th November FINAL Email - [email protected] | Internet - www.rfl.uk.com Pg 26 & 27 AUSTRALIA V NEW ZEALAND ENGLAND V NEW ZEALAND ELLAND ROAD STADIUM, LEEDS THE STOOP, LONDON GALPHARM STADIUM, HUDDERSFIELD The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the RFL Board of Directors. FAMILY TICKET OFFER GROUP STAGE FINAL OFFER* DISCOUNT RECEIVED ON Contributors - Tom Hoyle, Phil Caplan, Neil Barraclough, swpix.com, Dave Williams, John FOR 2 ADULTS AND OFFER Connaughton, Phil Hodgson, Dave Burke, Dave Woods, Callum Irving, Alex Ferguson 2 JUNIOR TICKETS for A FINAL TICKET WHEN £40 1010 for99 £10£10 PURCHASING ANY GROUP GAME If you are interested in advertising in the Rugby League Bulletin, please contact - [email protected] NOTE: ALL TICKET OFFERS Main Cover Photograph - The Angel of the North © The Rugby Football League Ltd 2009 Designed by - Tom Hoyle Tickets from £20 adults, £10 conc. -

Matches – 5 May 1973 –Leeds United 0 Sunderland 1

Matches – 5 May 1973 –Leeds United 0 Sunderland 1 FA Cup final – Wembley – 100,000 Scorers: None Leeds United: Harvey, Reaney, Cherry, Bremner, Madeley, Hunter, Lorimer, Clarke, Jones, Giles, E Gray (Yorath 77) Sunderland: Montgomery, Malone, Guthrie, Horswill, Watson, Pitt, Kerr, Porterfield, Halom, Hughes, Tueart One of the lowest points in the history of Leeds United Football Club came in early May 1973, as they sought to defend the FA Cup they won for the first time twelve months earlier. They were the hottest favourites for years, considered certainties to beat their Second Division opponents, rank outsiders Sunderland. A day that should have been one of celebration and triumph ended instead with United in a trough of depression and despair. “Everything points to a United victory” read the unusually confident headline of Don Revie‟s column for the Yorkshire Evening Post the Saturday before the final. The Leeds manager was in buoyant mood, The Leeds United team wave to the crowd before the match: writing: “Leeds United‟s experience of playing at Billy Bremner, David Harvey, Paul Reaney, Johnny Giles, Wembley is likely to prove the decisive factor in next Norman Hunter, Trevor Cherry, Peter Lorimer, Eddie Gray, Saturday‟s FA Cup final against Sunderland… As far Paul Madeley, Mick Jones, Terry Yorath, Allan Clarke as the FA Cup final is concerned, I consider the Sunderland players will suffer to a certain extent as none of them has played at Wembley previously. “This will be Leeds‟ fifth Wembley Cup final in eight years (including the 1968 League Cup final against Arsenal).