Servetus and Calvin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Paper Is a Descriptive Bibliography of Thirty-Three Works

Jennifer S. Clements. A Descriptive Bibliography of Selected Works Published by Robert Estienne. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. March, 2012. 48 pages. Advisor: Charles McNamara This paper is a descriptive bibliography of thirty-three works published by Robert Estienne held by the Rare Book Collection of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The paper begins with a brief overview of the Estienne Collection followed by biographical information on Robert Estienne and his impact as a printer and a scholar. The bulk of the paper is a detailed descriptive bibliography of thirty-three works published by Robert Estienne between 1527 and 1549. This bibliography includes quasi- facsimile title pages, full descriptions of the collation and pagination, descriptions of the type, binding, and provenance of the work, and citations. Headings: Descriptive Cataloging Estienne, Robert, 1503-1559--Bibliography Printing--History Rare Books A DESCRIPTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED WORKS PUBLISHED BY ROBERT ESTIENNE by Jennifer S. Clements A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina March 2012 Approved by _______________________________________ Charles McNamara 1 Table of Contents Part I Overview of the Estienne Collection……………………………………………………...2 Robert Estienne’s Press and its Output……………………………………………………2 Part II -

David Parsons

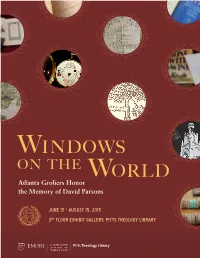

WINDOWS ON THE WORLD Atlanta Groliers Honor the Memory of David Parsons JUNE 15 - AUGUST 15, 2015 3RD FLOOR EXHIBIT GALLERY, PITTS THEOLOGY LIBRARY 1 WINDOWS ON THE WORLD: Atlanta Groliers Honor the Memory of David Parsons David Parsons (1939-2014) loved books, collected them with wisdom and grace, and was a noble friend of libraries. His interests were international in scope and extended from the cradle of printing to modern accounts of travel and exploration. In this exhibit of five centuries of books, maps, photographs, and manuscripts, Atlanta collectors remember their fellow Grolier Club member and celebrate his life and achievements in bibliography. Books are the windows through which the soul looks out. A home without books is like a room without windows. ~ Henry Ward Beecher CASE 1: Aurelius Victor (fourth century C.E.): On Robert Estienne and his Illustrious Men De viris illustribus (and other works). Paris: Robert Types Estienne, 25 August 1533. The small Roman typeface shown here was Garth Tissol completely new when this book was printed in The books printed by Robert Estienne (1503–1559), August, 1533. The large typeface had first appeared the scholar-printer of Paris and Geneva, are in 1530. This work, a late-antique compilation of important for the history of scholarship and learning, short biographies, was erroneously attributed to the textual history, the history of education, and younger Pliny in the sixteenth century. typography. The second quarter of the sixteenth century at Paris was a period of great innovation in Hebrew Bible the design of printing types, and Estienne’s were Biblia Hebraica. -

Galen's Elementary Course on Bones by CHARLES SINGER, M.D

25 Section of the History of Medicine 767 came into camp, after receiving an abdominal wound, holding up his bowels. This man survived to play the traitor on the Greeks and to sail off two days after his appearance in camp. There are two wounds of the flank, in one of which the wound is said to have let out the entrails, but in the second case "the spear thrust through the corselet, and though it tore clean off the flesh of the flank, it did not mingle with the bowels of the hero". Another wound described by Homer is well worth notice: Antilochos leaped on his opponent and wounded him "and severed all the vein that runs up the back till it reaches the neck". This is the only time that a vein is mentioned by Homer, and he could, of course, be referring to the aorta, although he has already defined the clavicle as separating the neck from the breast, and the aorta does not reach into the neck. But there is a continuous venous structure running along the back, namely the right innominate vein, the superior vena cava, the right auricle, and the inferior vena cava. These together may have been the structure referred to, the vein which was severed. In conclusion, it may be appropriate to ask the following question: Did Homer know of the frontal sinus? To answer this question in the affirmative one case may be considered: Antilochos slew a Trojan warrior, driving a spear through the helmet ridge into the warrior's brow, "and the point of the bronze passed within the bone". -

André Vésale (1514–1564) À La Conquête Des Publics (Ou Comment Acquérir Un Nom Immortel Dans L’Histoire Des Sciences En Insultant Ses Maîtres) Hélène Cazes

Document generated on 10/01/2021 10:59 a.m. Renaissance and Reformation Renaissance et Réforme La fabrique de la controverse : André Vésale (1514–1564) à la conquête des publics (ou Comment acquérir un nom immortel dans l’histoire des sciences en insultant ses maîtres) Hélène Cazes Tensions à l’âge de l’imprimé : conflit et concurrence des publics Article abstract dans la littérature française de la Renaissance When Andreas Vesalius published the Seven Books on the Fabric of the Human Tensions in the Age of Printing: Audience Conflict and Competition in Body in 1543, it was with satisfaction that he created a scandal in the field of French Literature of the Renaissance medicine and, more generally, among cultivated European readers. Assuming Volume 42, Number 1, Winter 2019 a voice of authority in medicine at the age of twenty-eight, he developed his account of dissection as a series of personal observations and denunciations of URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1064522ar poor anatomists, beginning with his masters. But not only was this irreverence public, it also created a public, represented on the frontispiece of the work: it DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1064522ar established the book as a tribunal of science. The first victim to be tried was Jacques Dubois, professor in Paris’ Faculty of Medicine; his response, published See table of contents in 1551, fuelled a lengthy posthumous debate, feeding the controversy upon which Vesalius’s posterity is founded. Publisher(s) Iter Press ISSN 0034-429X (print) 2293-7374 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Cazes, H. -

Arts Et Savoirs, 15 | 2021 Giovanni Manardo and Jacques Dubois on John Mesuë’S Medical Substances 2

Arts et Savoirs 15 | 2021 Revisiting Medical Humanism in Renaissance Europe Giovanni Manardo and Jacques Dubois on John Mesuë’s Medical Substances Giovanni Manardo et Jacques Dubois à propos de la matière médicale de Jean Mesuë Dorothea Heitsch Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/aes/3798 DOI: 10.4000/aes.3798 ISSN: 2258-093X Publisher Laboratoire LISAA Printed version Date of publication: 1 June 2021 Electronic reference Dorothea Heitsch, “Giovanni Manardo and Jacques Dubois on John Mesuë’s Medical Substances”, Arts et Savoirs [Online], 15 | 2021, Online since 25 June 2021, connection on 26 June 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/aes/3798 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/aes.3798 This text was automatically generated on 26 June 2021. Centre de recherche LISAA (Littératures SAvoirs et Arts) Giovanni Manardo and Jacques Dubois on John Mesuë’s Medical Substances 1 Giovanni Manardo and Jacques Dubois on John Mesuë’s Medical Substances Giovanni Manardo et Jacques Dubois à propos de la matière médicale de Jean Mesuë Dorothea Heitsch 1 Opera Mesuae is a compilation of four texts: Canones universales, De simplicibus, Grabadin1, and Practica. These four texts originated in roughly ten Hebrew, some Italian, and more than seventy Latin manuscripts circulating in Europe from the thirteenth to the eighteenth century2. From the late fifteenth to the early seventeenth century, Mondino de Liuzzi, Giovanni Manardo3, Jacques Dubois (Jacobus Sylvius; who was also responsible for the Neo-Latin translation), and Giovanni Costeo added commentaries and additions to subsequent editions of Opera Mesuae. In the following pages, I show that this medical database is at the crossroads of translation, exchange, humanistic rhetoric, the medical schools of Italy and France, printing, and transnational conversations. -

Andreas Vesalius, the Predecessor of Neurosurgery: How His Progressive

Historical Vignette Andreas Vesalius, the Predecessor of Neurosurgery: How his Progressive Scientific Achievements Affected his Professional Life and Destiny Bruno Splavski1-3, Kresimir Rotim1,2, Goran Lakicevi c4, Andrew J. Gienapp5,6, Frederick A. Boop5-7, Kenan I. Arnautovic6,7 Key words Andreas Vesalius, the father of modern anatomy and a predecessor of neuro- - 16th Century science, was a distinguished medical scholar and Renaissance figure of the 16th - Anatomy - Andreas Vesalius Century Scientific Revolution. He challenged traditional anatomy by applying - Death empirical methods of cadaveric dissection to the study of the human body. His - Neuroscience revolutionary book, De Humani Corporis Fabrica, established anatomy as a - Pilgrimage scientific discipline that challenged conventional medical knowledge, but often From the 1Department of Neurosurgery, Sestre Milosrdnice caused controversy. Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain to University Hospital Center, Zagreb, Croatia; 2Osijek whom De Humani was dedicated, appointed Vesalius to his court. While in 3 University School of Medicine, Osijek, Croatia; Osijek Spain, Vesalius’ work antagonized the academic establishment, current medical University School of Dental Medicine and Health, Osijek, Croatia; 4Mostar University Hospital, Mostar, Bosnia and knowledge, and ecclesial authority. Consequently, his methods were unac- Herzegovina; 5Neuroscience Institute, Le Bonheur Children’s ceptable to the academic and religious status quo, therefore, we believe that his 6 Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee, USA; Semmes-Murphey professional life—as well as his tragic death—was affected by the political Clinic, Memphis, Tennessee, USA; and 7Department of Neurosurgery, University of Tennessee Health Science state of affairs that dominated 16th Century Europe. Ultimately, he went on a Center, Memphis, Tennessee, USA pilgrimage to the Holy Land that jeopardized his life. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 04 April 2018 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: O'Brien, John (2015) 'A book (or two) from the Library of La Bo¡etie.',Montaigne studies., 27 (1-2). pp. 179-191. Further information on publisher's website: https://classiques-garnier.com/montaigne-studies-2015-an-interdisciplinary-forum-n-27-montaigne-and-the-art- of-writing-a-book-or-two-from-the-library-of-la-boetie.html Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk A Book (or Two) from the Library of La Boétie John O’Brien The copy of the Greek editio princeps of Cassius Dio, now in Eton College, has long been recognized as formerly belonging to Montaigne (figure 1).1 It bears his signature in the usual place and in his usual style. -

2003 Calvin Bibliography

2003 Calvin Bibliography Compiled by Paul Fields I. Calvin’s Life and Times A. Biography B. Cultural ContextIntellectual History C. Cultural ContextSocial History D. Friends and Associates E. Polemical Relationships II. Calvin’s Works A. Works and Selections B. Critique III. Calvin’s Theology A. Overview B. Doctrine of God 1. Knowledge of God 2 . Providence 3. Sovereignty 4. Trinity C. Doctrine of Christ D. Doctrine of the Holy Spirit E. Doctrine of Salvation 1. Assurance 2. Justification 3. Predestination F. Doctrine of Humanity 1. Image of God 2. Natural Law 3. Sin G. Doctrine of the Christian Life 1. Ethics 2. Piety 3. Sanctification H. Ecclesiology 1. Overview 2. Discipline and Instruction 3. Missions 4. Polity I. Worship 1. Iconoclasm 2. Liturgy 3. Music 4. Prayer 5. Preaching and Sacraments J. Revelation 1. Exegesis and Hermeneutics 2. Scripture K. Apocalypticism L. Patristic and Medieval Influences M. Method IV. Calvin and SocialEthical Issues V. Calvin and Political Issues VI. Calvinism A. Theological Influence 1. Overview 2. Christian Life 3. Covenants 4. Discipline 5. Dogmatics 6. Ecclesiology 7. Education 8. Grace 9. God 10. Justification 11. Predestination 12. Revelation 13. Sacraments 14. Salvation 15. Worship B. Cultural Influence 1. Overview 2. Literature C. Social, Economic, and Political Influence D. International Influence 1. England 2. France 3. Germany 4. Hungary 5. Netherlands 6. South Africa 7. Transylvania 8. United States E. Critique VII. Book Reviews I. Calvin’s Life and Times A. Biography Brockington, William S., Jr. "John Calvin." In Dictionary of World Biography, Vol. 3: The Renaissance, edited by Frank N. -

Erasmus' Latin New Testament

A Most Perilous Journey ERASMUS’ GREEK NEW TESTAMENT AT 500 YEARS CURATED BY RICHARD M. ADAMS, JR. JULY 15, 2016 — SEPT 15, 2016 PITTS THEOLOGY LIBRARY 1 A Most Perilous Journey: Erasmus’ Greek New Testament at 500 Years “I have edited the New Five hundred years ago, the great Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus Testament, and much of Rotterdam (1466-1536) published the first Greek New Testament besides; and in order to and a new Latin translation, a landmark event in the development do a service to the reading of the Bible and a sign of the emphasis on returning ad fontes (“to public I have thought the sources”) that characterized developing reforms of the church. nothing of a most perilous This exhibit celebrates the milestone by displaying all five editions of journey, nothing of the Erasmus’ Greek New Testament produced during his lifetime, allowing expense, nothing at all of visitors to trace how the text changed over the decades of Erasmus’ the toils in which I have work. Alongside these rare Erasmus editions, items in the exhibit worn out a great part of highlight the changing form of the Bible in the sixteenth century my health and life itself.” and the development of Erasmus as a scholar and his philological and theological work in this critical time of reform. In response to receiving Erasmus’ first edition of the Greek New Testament, his friend John Colet (1466-1519), Dean at St. Paul’s Cathedral, wrote, “The name of Erasmus shall never perish.” We welcome you to this exhibit, celebrating the fact that after 500 years the sentiment remains strong. -

SYLVIUS and the REFORM of ANATOMY by C

SYLVIUS AND THE REFORM OF ANATOMY by C. E. KELLETT THE first half of the sixteenth century in France is characterized by a rapid change in the ways of thinking and learning, and of the structure of society itself, by the emergence ofa wealthy and educated middle class. The institutions of the planned medieval state survived but often with a curious change in balance. Philosophy became closely allied with Humanism and flourished not in the schools of the Faculty ofTheology but amongst the colleges of theJunior Faculty of Arts.' The most influential of its teachers, Le Fevre, who played so important a part in the reformation, was a Master of Arts who began his studies in Theology but never became even a Bachelor in that Faculty.2 In the same way Sylvius, who was a pupil of Le Fevre and also from Picardy, achieved his reformation of anatomical training within the colleges of the Junior Faculty and, though long after he had achieved fame as an Anatomist, he took his Doctorate at Montpellier, he never proceeded to the Licence of the Faculty in Paris, remaining a Bachelor.3 There are at present over 6o,ooo students in the University of Paris, perhaps four times as many as there were then, for the Venetian Ambassador, Marino Cavalli, is quoted by Lefranc as reporting in I546 that there were I6-20,000 students, for the most part impoverished, in the University and that there was no lack ofteachers who were, ifanything poorer, or as Lefranc puts it, 'bien chetifs'. Many of these were studying for a higher degree in Law or Divinity but by a special act5 it was not possible to do this while taking the course for a degree in Medicine. -

Eponymic Structures in Human Anatomy

THE GLASGOW MEDICAL JOURNAL. No. VI. December, 1895. ORIGINAL ARTICLES. EPONYMIC STRUCTURES IN HUMAN ANATOMY. By JAMES FINLAYSON, M.D., Physician to the Glasgow Western Infirmary and to the Royal Hospital for Sick Children ; Honorary Librarian to the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons, Glasgow, &c. During last winter on6 of my "bibliographical demonstrations" in our Faculty library here was designed to illustrate eponymic structures in anatomy. I had often felt that the names of great men in our profession which had happened to be preserved in the nomenclature of anatomy furnished about the only instruction in the history of medicine which many of our students acquired. Every one knows at least the name of Herophilus in this way; and not a few know that he was of the Alexandrian school before the Christian era. How many know as much of his equally famous contemporary, Erasistratus ? But the names attached to the structures they are studying are usually mere names: very often not even the vaguest idea of their date or nationality is associated with them. How many of our students, in speaking of the capsule of Glisson or the foramen of Winslow, know whether Glisson or Winslow was an Englishman ? In preparing my demonstration I had the aid of two of my clinical assistants?Dr. John Love and Dr. John W. Findlay? No. 6. 2 C Vol. XLIV. 402 Dr. Finlayson?Eponymic Structures in Anatomy. without whose help I could not possibly have attempted the work. We searched out all the eponymic structures we could find, and then we searched out the books or papers of the authors, where these are described by them, whenever this was possible. -

“A Sacrifice Well Pleasing to God”: John Calvin and the Missionary Endeavor of the Church1 Michael A

“A Sacrifice Well Pleasing to God”: John Calvin and the Missionary Endeavor of the Church1 Michael A. G. Haykin Michael A. G. Haykin is IntroductIon was its continuity with the missionary passion of Professor of Church History and t has often been main - the Apostles. In his mind, Roman Catholicism’s Biblical Spirituality at The Southern Itained that the sixteenth- missionary activity was indisputable and this sup- Baptist Theological Seminary. century Reformers had a poorly- plied a strong support for its claim to stand in He is also Adjunct Professor of developed missiology and that solidarity with the Apostles. As Bellarmine main- Church History and Spirituality overseas missions to non-Chris- tained, at Toronto Baptist Seminary in tians was an area to which they Ontario, Canada. Dr. Haykin is the gave little thought. Yes, this argu- [I]n this one century the Catholics have con- author of many books, including The Revived Puritan: The Spirituality ment runs, they rediscovered the verted many thousands of heathens in the new of George Whitefield (Joshua Press, apostolic gospel, but they had no world. Every year a certain number of Jews are 2000), “At the Pure Fountain of vision to spread it to the utter- converted and baptized at Rome by Catholics Thy Word”: Andrew Fuller As an 2 who adhere in loyalty to the Bishop of Rome…. Apologist (Paternoster Press, 2004), most parts of the earth. Possi- Jonathan Edwards: The Holy Spirit in bly the very first author to raise The Lutherans compare themselves to the Revival (Evangelical Press, 2005), the question about early Protes- apostles and the evangelists; yet though they have and The God Who Draws Near: An tantism’s failure to apply itself to among them a very large number of Jews, and in Introduction to Biblical Spirituality (Evangelical Press, 2007).