John Calvin's Use of Erasmus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Paper Is a Descriptive Bibliography of Thirty-Three Works

Jennifer S. Clements. A Descriptive Bibliography of Selected Works Published by Robert Estienne. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. March, 2012. 48 pages. Advisor: Charles McNamara This paper is a descriptive bibliography of thirty-three works published by Robert Estienne held by the Rare Book Collection of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The paper begins with a brief overview of the Estienne Collection followed by biographical information on Robert Estienne and his impact as a printer and a scholar. The bulk of the paper is a detailed descriptive bibliography of thirty-three works published by Robert Estienne between 1527 and 1549. This bibliography includes quasi- facsimile title pages, full descriptions of the collation and pagination, descriptions of the type, binding, and provenance of the work, and citations. Headings: Descriptive Cataloging Estienne, Robert, 1503-1559--Bibliography Printing--History Rare Books A DESCRIPTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED WORKS PUBLISHED BY ROBERT ESTIENNE by Jennifer S. Clements A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina March 2012 Approved by _______________________________________ Charles McNamara 1 Table of Contents Part I Overview of the Estienne Collection……………………………………………………...2 Robert Estienne’s Press and its Output……………………………………………………2 Part II -

Calvinist Natural Law and the Ultimate Good

Vol 5 The Western Australian Jurist 153 CALVINIST NATURAL LAW AND THE ULTIMATE GOOD * CONSTANCE YOUNGWON LEE ABSTRACT Calvin’s natural law theory is premised on the sovereignty of God. In natural law terms, the ‘sovereignty of God’ doctrine prescribes that the normative standards for positive law originate from God alone. God is the sole measure of the ‘good’. This emphasis allows for a sharp separation between normative and descriptive dimensions. In this context, it would be a logical fallacy to maintain that anything humanly appointed can attain the status of self- evidence. However, in recent years, new natural law theorists have been guilty of conflating the normative and descriptive dimensions – a distinction that is critical to the discipline of natural law. This may stretch as far back to Aquinas who set human participation in the goods (‘practical reason’) as the rightful starting place for natural law. This paper explores Calvin’s natural law theory to show how his concept of ‘the ultimate good’ harnesses the potential to restore natural law theory to its proper order. By postulating a transcendent standard in terms of ‘the ultimate good’ – God Himself – Calvin’s natural law provides a philosophical framework for compelling positive laws in the pursuit of a higher morality. I INTRODUCTION “There is but one good; that is God. Everything else is good when it looks to Him and bad when it turns from Him”. C S LEWIS, The Great Divorce1 * Tutor and LLM Candidate, T C Beirne School of Law, University of Queensland. The author would like to acknowledge the contributions of several scholars, particularly Associate Professor Jonathan Crowe for his insightful remarks. -

Protestant Reformed Theological Journal

Protestant Reformed Theological j Journal VOLUME XXXV April, 2002 Number 2 In This Issue: Editor's Notes 1 Setting in Order the Things That Are Wanting (5) Robert D. Decker 2 A Comparison ofExegesis: John Calvin and Thomas Aquinas Russell J. Dykstra 15 The Serious Call of the Gospel - What Is the Well-Meant Offer of Salvation (2) Lau Chin Kwee 26 Nothing but a Loathsome Stench: Calvin"s Doctrine ofthe Spiritual Condition ofFallen Man David-J. Engelsma 39 Book Reviews 61 ++++ ISSN: 1070-8138 PROTESTANT REFORMED THEOLOGICAL JOURNAL Published twice annually by the faculty of the Protestant Reformed Theological Seminary: Robert D. Decker, Editor Russell J. Dykstra, Book Review Editor David J. Engelsma ++++ The Protestant Reformed Theological Joumal is published by the Protestant Reformed Theological Seminary twice each year, in April and November, and mailed to subscribers free of charge. Those who wish to receive the Journal should write the editor, at the seminary address. Those who wish to reprint an article appearing in the Journal should secure the permission of the editor. Books for review should be sent to the book review editor, also at the address ofthe school. Protestant Reformed Theological Seminary 4949 Ivanrest Avenue Grandville, MI 49418 USA EDITOR'S NOTES Prof. Russell J. Dykstra presents the first article ofa series on "A Comparison of Exegesis: John Calvin and Thomas Aquinas." Because of the stature of these two theologians (Calvin in the Protestant, Le., especially Reformed Protestant tradition; Aquinas in the Roman Catholic tradition), Dykstra points out that for these two men to be "compared and contrasted in many areas oftheirwork and thought is only natural." And indeed there are many works published contrasting these giants. -

Calvin Against the Calvinists in Early Modern Thomism

chapter 14 Calvin against the Calvinists in Early Modern Thomism Matthew T. Gaetano Reformed Protestants opposed to Arminianism saw themselves as aligned with the Dominican Thomists who opposed the accounts of free choice provided by Luis de Molina (1535– 1600) and many of his fellow Jesuits.1 Do- minicans and Reformed Protestants both defended a fiercely anti- Pelagian doctrine of predestination, reprobation, and intrinsically efficacious grace, while Jesuits, Arminians, and some Lutherans honed notions like middle knowledge out of concern that their opponents, whether Roman Catholic or Protestant, destroyed free choice and made God the author of sin.2 Scholars have recognized these cross- confessional resemblances, and this volume has helped to clarify the substantive borrowings. Reformed theologians clearly expressed their sense of a common outlook on predestination, reprobation, and the relationship of grace and free choice not only with Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274) but also with post- Tridentine Dominicans.3 At times, they employed 1 The title is a reference to Basil Hall, “Calvin against the Calvinists,” in John Calvin: A Collection of Distinguished Essays, ed. Gervase Duffield (Grand Rapids: 1966), 19– 37. But, in contrast with Hall, the Dominicans examined in this essay generally praised the (supposed) depar- tures of later Reformed theologians from John Calvin. For an excellent discussion of the problems with Hall’s approach and with the term Calvinist, see Richard A. Muller, Calvin and the Reformed Tradition: On the Work of Christ and the Order of Salvation (Grand Rapids: 2012), 15, 48, 52, 145, 159– 60. 2 Besides the contributions to this volume, see the clear account of the figures and issues in this debate in Willem J. -

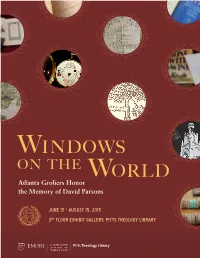

David Parsons

WINDOWS ON THE WORLD Atlanta Groliers Honor the Memory of David Parsons JUNE 15 - AUGUST 15, 2015 3RD FLOOR EXHIBIT GALLERY, PITTS THEOLOGY LIBRARY 1 WINDOWS ON THE WORLD: Atlanta Groliers Honor the Memory of David Parsons David Parsons (1939-2014) loved books, collected them with wisdom and grace, and was a noble friend of libraries. His interests were international in scope and extended from the cradle of printing to modern accounts of travel and exploration. In this exhibit of five centuries of books, maps, photographs, and manuscripts, Atlanta collectors remember their fellow Grolier Club member and celebrate his life and achievements in bibliography. Books are the windows through which the soul looks out. A home without books is like a room without windows. ~ Henry Ward Beecher CASE 1: Aurelius Victor (fourth century C.E.): On Robert Estienne and his Illustrious Men De viris illustribus (and other works). Paris: Robert Types Estienne, 25 August 1533. The small Roman typeface shown here was Garth Tissol completely new when this book was printed in The books printed by Robert Estienne (1503–1559), August, 1533. The large typeface had first appeared the scholar-printer of Paris and Geneva, are in 1530. This work, a late-antique compilation of important for the history of scholarship and learning, short biographies, was erroneously attributed to the textual history, the history of education, and younger Pliny in the sixteenth century. typography. The second quarter of the sixteenth century at Paris was a period of great innovation in Hebrew Bible the design of printing types, and Estienne’s were Biblia Hebraica. -

Commentary on Corinthians - Volume 1

Commentary on Corinthians - Volume 1 Author(s): Calvin, John (1509-1564) (Alternative) (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Commentary on Corinthians is an impressive commentary. Calvin is regarded as one of the Reformation©s best interpret- ers of scripture. He frequently offers his own translations of a passage, explaining the subtleties and nuances of his translation. He has a penchant for incorporating keen pastoral insight into the text as well. He always interacts with other theologians, commentators, and portions of the Bible when interpreting a particular passage. Further, this volume also contains informative notes from the editor. Calvin©s Comment- ary on Corinthians should not be ignored by anyone inter- ested in the books of Corinthians or John Calvin himself. Tim Perrine CCEL Staff Writer This volume contains Calvin©s commentary on the first 14 chapters of 1 Corinthians. Subjects: The Bible Works about the Bible i Contents Commentary on 1 Corinthians 1-14 1 Translator's Preface 2 Facsimile of Title Page to 1573 English Translation 16 Timme's 1573 Preface 17 Calvin's First Epistle Dedicatory 18 Calvin's Second Epistle Dedicatory 21 The Argument 24 Chapter 1 31 1 Corinthians 1:1-3 32 1 Corinthians 1:4-9 38 1 Corinthians 1:10-13 43 1 Corinthians 1:14-20 51 1 Corinthians 1:21-25 61 1 Corinthians 1:26-31 65 Chapter 2 71 1 Corinthians 2:1-2 72 1 Corinthians 2:3-5 74 1 Corinthians 2:6-9 78 1 Corinthians 2:10-13 85 1 Corinthians 2:14-16 89 Chapter 3 94 1 Corinthians 3:1-4 95 1 -

Reformed Tradition

THE ReformedEXPLORING THE FOUNDATIONS Tradition: OF FAITH Before You Begin This will be a brief overview of the stream of Christianity known as the Reformed tradition. The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, the Reformed Church in America, the United Church of Christ, and the Christian Reformed Church are among those considered to be churches in the Reformed tradition. Readers who are not Presbyterian may find this topic to be “too Presbyterian.” We encourage you to find out more about your own faith tradition. Background Information The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) is part of the Reformed tradition, which, like most Christian traditions, is ancient. It began at the time of Abraham and Sarah and was Jewish for about two thousand years before moving into the formation of the Christian church. As Christianity grew and evolved, two distinct expressions of Christianity emerged, and the Eastern Orthodox expression officially split with the Roman Catholic expression in the 11th century. Those of the Reformed tradition diverged from the Roman Catholic branch at the time of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. Martin Luther of Germany precipitated the Protestant Reformation in 1517. Soon Huldrych Zwingli was leading the Reformation in Switzerland; there were important theological differences between Zwingli and Luther. As the Reformation progressed, the term “Reformed” became attached to the Swiss Reformation because of its insistence on References Refer to “Small Groups 101” in The Creating WomanSpace section for tips on leading a small group. Refer to the “Faith in Action” sections of Remembering Sacredness for tips on incorporating spiritual practices into your group or individual work with this topic. -

Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve The Huguenots In April 1564 French colonists and soldiers under the command of Rene de Laudonniere came to Spanish controlled la Florida with the intent to build a permanent settlement at the mouth of the River of May (St. Johns River.) The settlement was originally planned as a commercial venture, but as conflicts with the Catholics continued in France, Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, a Huguenot, proposed that it also become a refuge for the Huguenots. The name give to the settlement was “la Caroline” after France’s young Huguenot Cross monarch, Charles. Who are the Huguenots are the followers of John province of Touraine to denote persons Huguenots? Calvin. The name Huguenot (oo-ga-no) who walk in the night because their is derived either from the German own safe places of worship were dark “eidgenossen” meaning “confederate” or caves or under the night sky. from “Hugeon,” a word used in the Who was In the early 1500’s Protestantism was explosion of anti-Protestant sentiment. John Calvin? gathering momentum all over Europe. Calvin wound up fleeing France and John Calvin (Jean Cauvin, 1509-1564), a settling in Geneva, Switzerland. young law student in Paris, read the writings and beliefs of Martin Luther. Calvin, who had previously studied to enter the priesthood, began to consider the Protestant call to put the scriptures first and to reform the church. In 1533 Calvin began to write about his own salvation experience. He followed this with a speech attacking the Roman Catholic Church and demanding a change like Martin Luther had initiated in Germany. -

The Legacy of Sovereign

LegacySovereignJoy.48134.int.qxd 9/21/07 10:01 AM Page 1 T HE L EGACY OF S OVEREIGN J OY LegacySovereignJoy.48134.int.qxd 9/21/07 10:01 AM Page 2 OTHER BOOKS BY THE AUTHOR The Justification of God: An Exegetical and Theological Study of Romans 9:1–23 2nd Edition (Baker Book House, 1993, orig. 1983) The Supremacy of God in Preaching (Baker Book House, 1990) The Pleasures of God: Meditations on God’s Delight in Being God (Multnomah Press, 1991) Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism (edited with Wayne Grudem, Crossway Books, 1991) What’s the Difference? Manhood and Womanhood Defined According to the Bible (Crossway Books, 1991) Let the Nations Be Glad: The Supremacy of God in Missions (Baker Book House, 1993) The Purifying Power of Living by Faith in Future Grace (Multnomah Press, 1995) Desiring God: Meditations of a Christian Hedonist (Multnomah Press, revised 1996) A Hunger for God: Desiring God through Fasting and Prayer (Crossway Books, 1997) A Godward Life: Savoring the Supremacy of God in All of Life (Multnomah Press, 1997) God’s Passion for His Glory: Living the Vision of Jonathan Edwards (Crossway Books, 1998) The Innkeeper (Crossway Books, 1998) A Godward Life, Book Two: Savoring the Supremacy of God in All of Life (Multnomah Press, 1999) LegacySovereignJoy.48134.int.qxd 9/21/07 10:01 AM Page 3 s a r e n a n o t w s s i l e e n h t t BOOK ONE LegTHEacy of Sovereign Joy God’s Triumphant Grace in the Lives of Augustine, Luther, and Calvin J OHN P IPER CROSSWAY BOOKS A PUBLISHING MINISTRY OF GOOD NEWS PUBLISHERS WHEAT O N , ILLINO IS LegacySovereignJoy.48134.int.qxd 9/21/07 10:01 AM Page 4 The Legacy of Sovereign Joy Copyright © 2000 by John Piper Published by Crossway Books a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers 1300 Crescent Street Wheaton, Illinois 60187 All rights reserved. -

Today, We Will Describe the Theological, Political, and Economic Ideas of the Reformation

Learning Objective Name _____________________ Today, we will describe the theological, political, and economic ideas of the Reformation. CFU What are we going to do today? Activate (or provide) Prior Knowledge Name some churches around your neighborhood. CFU Students, there are many different types of churches in and around your neighborhood. Today, you will see that many of these churches came about because of a split of the Catholic Church more than 500 years ago called the Reformation. Many new ideas came from the Reformation. Today, we will describe the theological, political, and economic ideas of the Reformation. th DataWORKS Educational Research 7 Grade History 9.2 (3Q) (800) 495-1550 • www.dataworks-ed.com Describe the theological, political, and economic ideas of the major figures ©2011 All rights reserved. during the Reformation (e.g., Desiderius Erasmus, Martin Luther, John Calvin, Comments? [email protected] William Tyndale). Lesson to be used by EDI trained-teachers only. Concept Development The Reformation was the religious reform1 movement in the 1500s that resulted in the separation of Protestant2 churches from the Roman Catholic Church. 1 change for the better 2 church that protested against the Catholic Church The separation during the Reformation resulted from differences in theological ideas which impacted3 political and economic ideas. Theological ideas are those which relate to religion. Political ideas relate to the government. Economic ideas relate to money. 3 changed Catholic Church During Reformation Ideas Beliefs and Ideas the Reformation (Protestant) Approach to Catholics approached God Each person should have a God through the intervention of the personal relationship with God. -

Luther and Calvin on Paul's Epistle to the Galatians

Martin Luther stated in his commentary on Galatians 1531/35, “For in my heart there rules this one doctrine, namely, faith in ÅA Christ. From it, through it, and to it all my theological thought Juha Mikkonen: ows and returns, day and night; yet I am aware that all I have Juha Mikkonen grasped of this wisdom in its height, width, and depth are a few poor and insignicant rstfruits and fragments.” John Calvin armed in his commentary on Galatians Luther and Calvin on Paul’s 1546/48, “It was necessary to indicate the fountain, so that Epistle to the Galatians his (Paul’s) readers should know that the controversy was not concerned with some insignicant trie, but with the most the Galatians Epistle to on Paul’s and Calvin Luther important matter of all, the way we obtain salvation”. An Analysis and Comparison of Substantial Concepts in Luther’s Both Luther’s and Calvin’s thought had an indisputable 1531/35 and Calvin’s 1546/48 Commentaries on Galatians importance for the 16th century, and their theology has continuing signicance to many Christian denominations today. Both Luther and Calvin saw Paul’s epistle to the Galatians as important and composed a commentary on it, which makes it exceptionally convenient to compare the two reformers’ thought. What are the distinctive central themes for the two reformers in their respective commentaries on Galatians? Is their thought similar on key issues in their commentaries on Galatians, such as justication, the work of the Holy Spirit, law, good works and ministry? Or are there signicant dierences in how they understand these important doctrines of the Christian faith? This analysis and comparison of substantial concepts in Luther’s 1531/35 and Calvin’s 1546/48 commentaries on Galatians suggests a greater degree of agreement on the above issues between the German and the Swiss reformer than has generally been acknowledged. -

1 the Summa Theologiae and the Reformed Traditions Christoph Schwöbel 1. Luther and Thomas Aquinas

The Summa Theologiae and the Reformed Traditions Christoph Schwöbel 1. Luther and Thomas Aquinas: A Conflict over Authority? On 10 December 1520 at the Elster Gate of Wittenberg, Martin Luther burned his copy of the papal bull Exsurge domine, issued by pope Leo X on 15 June of that year, demanding of Luther to retract 41 errors from his writings. The time for Luther to react obediently within 60 days had expired on that date. The book burning was a response to the burning of Luther’s works which his adversary Johannes Eck had staged in a number of cities. Johann Agricola, Luther’s student and president of the Paedagogium of the University, who had organized the event at the Elster Gate, also got hold of a copy of the books of canon law which was similarly committed to the flames. Following contemporary testimonies it is probable that Agricola had also tried to collect copies of works of scholastic theology for the burning, most notably the Summa Theologiae. However, the search proved unsuccessful and the Summa was not burned alongside the papal bull since the Wittenberg theologians – Martin Luther arguably among them – did not want to relinquish their copies.1 The event seems paradigmatic of the attitude of the early Protestant Reformers to the Summa and its author. In Luther’s writings we find relatively frequent references to Thomas Aquinas, although not exact quotations.2 With regard to the person of Thomas Luther could gleefully report on the girth of Thomas Aquinas, including the much-repeated story that he could eat a whole goose in one go and that a hole had to be cut into his table to allow him to sit at the table at all.3 At the same time Luther could also relate several times and in different contexts in his table talks how Thomas at the time of his death experienced such grave spiritual temptations that he could not hold out against the devil until he confounded him by embracing his Bible, saying: “I believe what is written in this book.”4 At least on some occasions Luther 1 Cf.