Erasmus' Latin New Testament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek?

2 Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek? Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek? A Concise Compendium of the Many Internal and External Evidences of Aramaic Peshitta Primacy Publication Edition 1a, May 2008 Compiled by Raphael Christopher Lataster Edited by Ewan MacLeod Cover design by Stephen Meza © Copyright Raphael Christopher Lataster 2008 Foreword 3 Foreword A New and Powerful Tool in the Aramaic NT Primacy Movement Arises I wanted to set down a few words about my colleague and fellow Aramaicist Raphael Lataster, and his new book “Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek?” Having written two books on the subject myself, I can honestly say that there is no better free resource, both in terms of scope and level of detail, available on the Internet today. Much of the research that myself, Paul Younan and so many others have done is here, categorized conveniently by topic and issue. What Raphael though has also accomplished so expertly is to link these examples with a simple and unambiguous narrative style that leaves little doubt that the Peshitta Aramaic New Testament is in fact the original that Christians and Nazarene-Messianics have been searching for, for so long. The fact is, when Raphael decides to explore a topic, he is far from content in providing just a few examples and leaving the rest to the readers’ imagination. Instead, Raphael plumbs the depths of the Aramaic New Testament, and offers dozens of examples that speak to a particular type. Flip through the “split words” and “semi-split words” sections alone and you will see what I mean. -

(CE:1227A-1228A) HEXAPLA and TETRAPLA, Two Editions of the Old Testament by ORIGEN

(CE:1227a-1228a) HEXAPLA AND TETRAPLA, two editions of the Old Testament by ORIGEN. The Bible was the center of Origen's religion, and no church father lived more in it than he did. The foundation, however, of all study of the Bible was the establishment of an accurate text. Fairly early in his career (c. 220) Origen was confronted with the fact that Jews disputed whether some Christian proof texts were to be found in scripture, while Christians accused the Jews of removing embarrassing texts from scripture. It was not, however, until his long exile in Caesarea (232-254) that Origen had the opportunity to undertake his major work of textual criticism. EUSEBIUS (Historia ecclesiastica 6. 16) tells us that "he even made a thorough study of the Hebrew language," an exaggeration; but with the help of a Jewish teacher he learned enough Hebrew to be able to compare the various Jewish and Jewish-Christian versions of the Old Testament that were extant in the third century. Jerome (De viris illustribus 54) adds that knowledge of Hebrew was "contrary to the spirit of his period and his race," an interesting sidelight on how Greeks and Jews remained in their separate communities even though they might live in the same towns in the Greco-Roman East. Origen started with the Septuagint, and then, according to Eusebius (6. 16), turned first to "the original writings in the actual Hebrew characters" and then to the versions of the Jews Aquila and Theodotion and the Jewish-Christian Symmachus. There is a problem, however, about the next stage in Origen's critical work. -

Novum Testamentum Graece Nestle-Aland 28Th Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

NOVUM TESTAMENTUM GRAECE NESTLE-ALAND 28TH EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Eberhard Nestle | 9781619700307 | | | | | Novum Testamentum Graece Nestle-Aland 28th edition PDF Book Book ratings by Goodreads. It is a very nice sewn binding. Three reasons for ordering Reasonable prices International shipping Secure payment. Answer: Thank you for your question. You are commenting using your Twitter account. Follow us. No additional fonts needed. Holman Christian Standard. Das neue Testament Griechisch A must see site! Canons and books. The site also containscomputer software containing the versions and free Bible study tools. American Standard Version. We try our best to provide a competitive shipping experience for our customers. When I find out I will post the information as an update. This edition introduced a separate critical apparatus and finally introduced consistency to the majority reading principle. It is sewn and flexible. The New Testament arrived in a cardboard box from Hendrickson. It feels like a high quality Bible paper. Aland submitted his work on NA to the editorial committee of the United Bible Societies Greek New Testament of which he was also a member and it became the basic text of their third edition UBS3 in , four years before it was published as the 26th edition of Nestle-Aland. The Greek text of the 28th edition is the same as that of the 5th edition of the United Bible Societies The Greek New Testament abbreviated UBS5 although there are a few differences between them in paragraphing, capitalization, punctuation and spelling. Essential We use cookies to provide our services , for example, to keep track of items stored in your shopping basket, prevent fraudulent activity, improve the security of our services, keep track of your specific preferences e. -

This Paper Is a Descriptive Bibliography of Thirty-Three Works

Jennifer S. Clements. A Descriptive Bibliography of Selected Works Published by Robert Estienne. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. March, 2012. 48 pages. Advisor: Charles McNamara This paper is a descriptive bibliography of thirty-three works published by Robert Estienne held by the Rare Book Collection of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The paper begins with a brief overview of the Estienne Collection followed by biographical information on Robert Estienne and his impact as a printer and a scholar. The bulk of the paper is a detailed descriptive bibliography of thirty-three works published by Robert Estienne between 1527 and 1549. This bibliography includes quasi- facsimile title pages, full descriptions of the collation and pagination, descriptions of the type, binding, and provenance of the work, and citations. Headings: Descriptive Cataloging Estienne, Robert, 1503-1559--Bibliography Printing--History Rare Books A DESCRIPTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED WORKS PUBLISHED BY ROBERT ESTIENNE by Jennifer S. Clements A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina March 2012 Approved by _______________________________________ Charles McNamara 1 Table of Contents Part I Overview of the Estienne Collection……………………………………………………...2 Robert Estienne’s Press and its Output……………………………………………………2 Part II -

The Cathedral Church of Saint Asaph; a Description of the Building

SAINT ASAPH THE CATHEDRAL AND SEE WITH PLAN AND ILLUSTRATIONS BELL'S CATHEDRAL SERIES College m of Arskiitecture Liorary Coraell U»iversity fyxmll Utttomitg JilratJg BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hettrg HI. Sage 1S91 A,'i..c.^.'^...vs> Vfe\p^.\.\:gr... 1357 NA 5460.53™"""'™""'"-"'"'^ The cathedral church of Saint Asaph; a de 3 1924 015 382 983 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924015382983 BELL'S CATHEDRAL SERIES SAINT ASAPH 7^^n{M3' 7 ^H THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF SAINT ASAPH A DESCRIPTION OF THE BUILD- ING AND A SHORT HISTORY OF THE SEE BY PEARCE B. IRONSIDE BAX WITH XXX ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON GEORGE BELL & SONS 1904 A/A , " S4-fcO CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON. ' PREFACE The author published a monograph on " St. Asaph Cathedral in 1896, which has formed the basis of the present handbook. The historical documents are few, and the surviving evidence of the past with regard to our smallest cathedral is scanty at the best. The chief books of reference have been Browne Willis's valuable "Survey of St. Asaph,'' published in 1720, also Edwards' edition of the same published at Wrexham in 1801, and the learned work by the Ven. Archdeacon Thomas, M.A., F.S.A., on " The Diocese of St. Asaph." " Storer's Cathedrals," pub- lished in i8ig, together with similar works, have also been consulted. -

The Impact and Influence of Erasmus's Greek New Testament

HISTORICAL STUDIES The Impact and Influence of Erasmus’s Greek New Testament PETER J. GOEMAN Abstract Although often eclipsed by the giants of the Reformation, Desiderius Erasmus had a notable influence on the Reformation and the world that followed. Responsible for five editions of the Greek New Testament, his contributions include a renewed emphasis on the Greek over against the Latin of the day, as well as influence on subsequent Greek New Testaments and many translations, including Luther’s German Bible and the English King James Version. In God’s providence, Erasmus provided kindling for the fire of the Reformation.1 “ he name of Erasmus shall never perish.” Time has proved these words, spoken by one of his friends in the early 1500s, to be true. Today, Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam is recognized as a key figure—especially in regard to his influence on Bible translation and textual criticism. Although his fame has been Tsuperseded by the heroes of the Reformation, many of them were benefi- ciaries of his hard work. The Reformers owed him much. In the English- speaking world, the average person may not know Erasmus’s name, yet those who read the Bible today are indebted both to his contribution and to those he influenced. 1 I would like to thank my friends and colleagues Abner Chou and Will Varner for reading an earlier version of this article and providing valuable feedback. 69 70 UNIO CUM CHRISTO ›› UNIOCC.COM Much has been written about Erasmus’s life, and this article will focus on his work on the Greek New Testament. -

In Praise of Folly: a Cursory Review and Appreciation Five Centuries Later

Page 1 of 7 Original Research In Praise of Folly: A cursory review and appreciation five centuries later Author: Desiderius Erasmus was a humanist reformer concerned with reforming the civil and 1 Raymond Potgieter ecclesiastical structures of his society. In reformed circles, much attention is paid to his role in Affiliation: the Lutheran controversy. Despite this, his powerful influence continues to this day. Erasmus’ 1Faculty of Theology, particular fool’s literature, Moriae Encomium (1509), revealed his humanist concerns for civil North-West University, and ecclesial society as a whole. He employed folly as a rhetorical instrument in satirical Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa manner, evoking readers’ amusement from numerous charges against the perceived multi- layered social reality of the day. Five hundred years later the person of Folly may still perform Correspondence to: this same task in Christian society. That was Erasmus’ point – the church is not to be seen as Raymond Potgieter an island, it shares in the structures of society and is therefore still subject to its share of critical Email: comments. [email protected] Postal address: PO Box 19491, Noordbrug ‘Lof der Zotheid’: ‘n oorsig en evaluering vyf eeue later. Desiderius Erasmus was ’n humanis 2522, South Africa wat gepoog het om hom te beywer vir die hervorming van die burgerlike en kerklike strukture Dates: van sy tyd. In gereformeerde kringe word sy rol in die Lutherse twisgeskil beklemtoon. Received: 30 Mar. 2015 Sy verreikende invloed word steeds vandag gevoel. Erasmus se gekke-literatuur, Moriae Accepted: 23 July 2015 Encomium (1509), het sy besorgdheid rakende die burgerlike en ekklesiastiese samelewing Published: 29 Sept. -

Beyond the Bosphorus: the Holy Land in English Reformation Literature, 1516-1596

BEYOND THE BOSPHORUS: THE HOLY LAND IN ENGLISH REFORMATION LITERATURE, 1516-1596 Jerrod Nathan Rosenbaum A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Jessica Wolfe Patrick O’Neill Mary Floyd-Wilson Reid Barbour Megan Matchinske ©2019 Jerrod Nathan Rosenbaum ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Jerrod Rosenbaum: Beyond the Bosphorus: The Holy Land in English Reformation Literature, 1516-1596 (Under the direction of Jessica Wolfe) This dissertation examines the concept of the Holy Land, for purposes of Reformation polemics and apologetics, in sixteenth-century English Literature. The dissertation focuses on two central texts that are indicative of two distinct historical moments of the Protestant Reformation in England. Thomas More's Utopia was first published in Latin at Louvain in 1516, roughly one year before the publication of Martin Luther's Ninety-Five Theses signaled the commencement of the Reformation on the Continent and roughly a decade before the Henrician Reformation in England. As a humanist text, Utopia contains themes pertinent to internal Church reform, while simultaneously warning polemicists and ecclesiastics to leave off their paltry squabbles over non-essential religious matters, lest the unity of the Church catholic be imperiled. More's engagement with the Holy Land is influenced by contemporary researches into the languages of that region, most notably the search for the original and perfect language spoken before the episode at Babel. As the confusion of tongues at Babel functions etiologically to account for the origin of all ideological conflict, it was thought that the rediscovery of the prima lingua might resolve all conflict. -

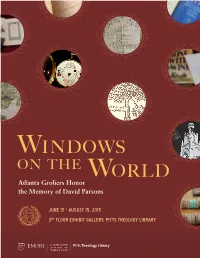

David Parsons

WINDOWS ON THE WORLD Atlanta Groliers Honor the Memory of David Parsons JUNE 15 - AUGUST 15, 2015 3RD FLOOR EXHIBIT GALLERY, PITTS THEOLOGY LIBRARY 1 WINDOWS ON THE WORLD: Atlanta Groliers Honor the Memory of David Parsons David Parsons (1939-2014) loved books, collected them with wisdom and grace, and was a noble friend of libraries. His interests were international in scope and extended from the cradle of printing to modern accounts of travel and exploration. In this exhibit of five centuries of books, maps, photographs, and manuscripts, Atlanta collectors remember their fellow Grolier Club member and celebrate his life and achievements in bibliography. Books are the windows through which the soul looks out. A home without books is like a room without windows. ~ Henry Ward Beecher CASE 1: Aurelius Victor (fourth century C.E.): On Robert Estienne and his Illustrious Men De viris illustribus (and other works). Paris: Robert Types Estienne, 25 August 1533. The small Roman typeface shown here was Garth Tissol completely new when this book was printed in The books printed by Robert Estienne (1503–1559), August, 1533. The large typeface had first appeared the scholar-printer of Paris and Geneva, are in 1530. This work, a late-antique compilation of important for the history of scholarship and learning, short biographies, was erroneously attributed to the textual history, the history of education, and younger Pliny in the sixteenth century. typography. The second quarter of the sixteenth century at Paris was a period of great innovation in Hebrew Bible the design of printing types, and Estienne’s were Biblia Hebraica. -

10. Why Didn't Jesus Use the Septuagint?

10 Q Did Jesus and the apostles, including Paul, quote from the Septuagint? A There are absolutely no manuscripts pre-dating the third century A.D. to validate the claim that Jesus or Paul quoted a Greek Old Testament. Quotations by Jesus and Paul in new versions’ New Testaments may match readings in the so-called Septuagint because new versions are from the exact same corrupt fourth and fifth century A.D. manuscripts which underlie the document sold today and called the Septuagint. These manuscripts are Alexandrinus, Vaticanus, and Sinaiticus. According to the colophon on the end of Sinaiticus, it came from Origen’s Hexapla. The others likely did also. Even church historians, Jerome, Hort, and our contemporary D.A. Carson, would agree that this is probably true. Origen wrote his Hexapla two hundred years after the life of Christ and Paul! NIV New Testament and Old Testament quotes may match occasionally because they were both penned by the same hand — a hand which recast both Old and New Testament to suit his Platonic and Gnostic leanings. New versions take the Sinaiticus, Vaticanus, and Alexandrinus manuscripts — which are in fact Origen’s Hexapla — and change the traditional Masoretic Old Testament text to match these. Alfred Martin, who was a past vice- president of Moody Bible Institute, called Origen “unsafe.” Origen’s Hexapla is a very unsafe source to use to change the historic Old Testament. The preface of the Septuagint marketed today points out that the stories surrounding the B.C. (before Christ) creation of the Septuagint (LXX) and the existence of a Greek Old Testament are based on fables. -

Introduction – Manifold Reader Responses: the Reception of Erasmus in Early Modern Europe

INTRODUCTION – MANIFOLD READER RESPONSES: THE RECEPTION OF ERASMUS IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE Karl Enenkel Erasmus provides one of the most interesting cases not only for the pro- cesses of early modern image and reputation building through publishing in print,1 but at the same time – and certainly not to a lesser degree – for the impossibility of controlling one’s reception before an audience that was continually growing, was increasingly emancipated, heterogeneous, and fragmented, and was, above all, constantly changing. This loss of control is especially striking, since Erasmus had been so successful in building up his literary and scholarly fame by shrewdly utilizing both the hierarchical organization of early modern intellectual life and the means of the new medium of the printed book. From the second decade of the 16th century onward, Erasmus succeeded in gaining an immense, hitherto unrivalled fame spread over the whole of Latin-writing and Latin-loving Europe. Erasmus fought his crusade for fame by means of his Latin works – which he had printed at such important publishers as Josse Bade (Paris), Aldus Manutius (Venice), Johannes Froben (Basel), and Mathias Schürer (Strasbourg) – especially the Adagia; De duplici copia; his translation and paraphrases of and commentaries on the New Testament; his edition of Hieronymus, including a new Life of St. Jerome; the Ciceronianus; and the Laus Stultitiae. By their very appearance, all of these works caused seri- ous earthquakes in intellectual life with respect to philological criticism, authentic Latin style, and religious, ethical, and social criticism. Since Erasmus was so successful in spreading his fame all over Europe that almost all intellectuals of that era were, in some way or another, acquainted with his name (even if they did not have the opportunity to carefully study his works), one could be tempted to think that “Eras- mus” or “Erasmian” became a kind of intellectual trademark or brand. -

Die Privatbibliothek Rudolph Gwalthers

Die Privatbibliothek Rudolph Gwalthers Autor(en): Leu, Urs B. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Librarium : Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Bibliophilen- Gesellschaft = revue de la Société Suisse des Bibliophiles Band (Jahr): 39 (1996) Heft 2 PDF erstellt am: 24.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-388609 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch URS B.LEU DIE PRIVATBIBLIOTHEK RUDOLPH GWALTHERS Die noch weitgehend erhaltene Bibliothek ren Jahrhunderten geschaffen wurden und Rudolph Gwalthers (1519-1586), des deren Bestände daher grundsätzlich auch späteren Nachfolgers Heinrich Bullingers erst nach der Simmlerschen Schenkung als Vorsteher der Zürcher Kirche, besteht eingingen. Gewisse Handexemplare gelangten aus sechs handschriftlichen1 und 368 auf unbekannten Wegen in andere gedruckten Werken.