Masters Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download NOW!

Bassic Fundamentals Course Take The Next Step On Your Bass Journey A Massive 10 Hours Of Lessons Covering Every Area Of Playing “Every bass player starts with the same goal - a solid foundation Building a strong, all-round set of bass skills can be hard work, especially when there are holes in that foundation. To avoid any pit falls you need a structured study program with a clear, simple road map covering every aspect of playing. That can be hard to find! To remedy this problem, I created Bassic Fundamentals, a huge course covering the basics of every essential area from technique to bass line creation to music theory, sight reading, bass setup, effects and much, much more. It really is a one size fits all course. Bassic Fundamentals will provide you with the skills necessary to easily progress and develop your bass playing in any area or style you desire – always building on a strong core and foundation” Mark J Smith (Creator of Talkingbass) “I took the Basic Fundamentals course shortly after picking up the instrument. Nine months after picking up the instrument and 6 months after starting the course, I went to an audition.” Mark Mahoney – USA “I play in church most weeks and wouldn’t have got anywhere near the level I’m at without these lessons.” Rob P. – Australia “After about six months of getting nowhere, I bought the Bassic Fundamentals course. My playing has been turbo charged.” Matthew Ogilvie – Western Canada “Bassic Fundamentals gave me a good starting point for practising different techniques.” Alexander Fuchs – Germany Bassic Fundamentals Course Breakdown Module 1: The Core Foundation Lesson 1-1 Course Introduction In this lesson we look at the course ahead and the kind of topics we’ll be covering Lesson 1-2 Practice Tips & Warmups Here we look at how to create a simple practice routine and work through some basic warmup exercises both on and away from the instrument Lesson 1-3 Tuning In this lesson we look at several different ways of tuning the bass: Tuning to an open string; Tuning with harmonics; Using an electronic tuner. -

Vanguard Jazz Orchestra Plans May Tribute to Thad Jones and Mel Lewis

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • March 30, 2005 Volume 1, Number 19 • $7.95 In This Issue: Mack Avenue to Sponsor Detroit Jazz Fest. 4 WGBH Ups Rivero to Radio/ TV GM . 5 Camilo Embarks . 6 441 Launches Test of Time . 9 Reviews and Picks. 15 Jazz Radio . 18 Smooth Jazz Radio. 23 RADIO Q&A: Radio WEMU’S Panels. 27 LINDA YOHN News. 4 page 12 Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Joey DeFrancesco #1 Smooth Album – Dave Koz #1 Smooth Single – Dave Koz JazzWeek This Week EDITOR Ed Trefzger ’m thrilled that we get to feature another of our favorite people CONTRIBUTING EDITORS in jazz radio this week, WEMU music director Linda Yohn. Keith Zimmerman Kent Zimmerman ILinda is a nominee for the Jazz Journalists Association Excel- Tad Hendrickson lence in Jazz Broadcasting/Willis Conover-Marian McPartland CONTRIBUTING WRITER Award. She has been there encouraging and supporting our ef- Tom Mallison forts even before there was a JazzWeek, as one of the first par- PHOTOGRAPHY ticipants on the Jazz Programmers Mailing List. Linda has been Barry Solof a key figure at each of JazzWeek’s Summits and an active part of PUBLISHER the industry tracks at IAJE for years. As host of the 9 a.m. to noon Tony Gasparre shift on WEMU, Linda shows everyone how jazz radio should be ADVERTISING: Contact Tony Gasparre done, and thanks to the ’net, those of us outside of Ypsilanti/Ann (585) 235-4685 x3 or Arbor/Detroit get to eavesdrop. email: [email protected] While we’re talking about the Motor City, hats off to Mack SUBSCRIPTIONS: Prices in US Dollars: Avenue Records for picking up the sponsorship of the Detroit In- Charter Rate: $199.00 per year, ternational Jazz Festival. -

Grant Green Grantstand Mp3, Flac, Wma

Grant Green Grantstand mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Grantstand Country: US Released: 1961 Style: Soul-Jazz, Hard Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1122 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1402 mb WMA version RAR size: 1247 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 707 Other Formats: WAV MP3 MP1 MIDI AIFF VQF DTS Tracklist Hide Credits Grantstand A1 Written-By – Green* My Funny Valentine A2 Written-By – Rodgers-Hart* Blues In Maude's Flat B1 Written-By – Green* Old Folks B2 Written-By – Hill*, Robison* Companies, etc. Published By – Groove Music Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Credits Drums – Al Harewood Guitar – Grant Green Liner Notes – Nat Hentoff Organ – Jack McDuff* Photography By [Cover Photo] – Francis Wolff Producer – Alfred Lion Recorded By [Recording By] – Rudy Van Gelder Tenor Saxophone, Flute – Yusef Lateef Notes Recorded on August 1, 1961, Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Blue Note Records Inc., 43 W 61st St., New York 23 (Adress on Back Cover) Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side A Label): BN 4086-A Matrix / Runout (Side B Label): BN 4086-B Matrix / Runout (Side A Runout etched): BN-LP-4086-A Matrix / Runout (Side B Runout etched): BN-LP-4086-B Rights Society: BMI Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Blue Grant Grantstand (LP, BN 84086, BN 4086 Note, BN 84086, BN 4086 Japan 1992 Green Album, Ltd, RE) Blue Note Grant Grantstand (CD, 7243 5 80913 2 8 Blue Note 7243 5 80913 2 8 US 2003 Green Album, RE, RM) Grantstand (CD, Blue TOCJ-9244, -

Hammond Sk1-73

Originally printed in the October 2013 issue of Keyboard Magazine. Reprinted with the permission of the Publishers of Keyboard Maga- zine. Copyright 2008 NewBay Media, LLC. All rights reserved. Keyboard Magazine is a Music Player Network publication, 1111 Bayhill Dr., St. 125, San Bruno, CA 94066. T. 650.238.0300. Subscribe at www.musicplayer.com REVIEW SYNTH » CLONEWHEEL » VIRTUAL PIANO » STANDS » MASTERING » APP HAMMOND SK1-73 BY BRIAN HO HAMMOND’S SK SERIES HAS SET A NEW PORTABILITY STANDARD FOR DRAWBAR that you’re using for pianos, EPs, Clavs, strings, organs that also function as versatile stage keyboards in virtue of having a comple- and other sounds. ment of non-organ sounds that can be split and layered with the drawbar section. Even though there isn’t a button that causes Where the original SK1 had 61 keys and the SK2 added a second manual, the new the entire keyboard to play only the lower organ SK1-73 and SK1-88 aim for musicians looking for the same sonic capabilities in a part—useful if you want to switch between solo single-slab form factor that’s more akin to a stage piano. I got to use the 73-key and comping sounds without disturbing the sin- model on several gigs and was very pleased with its sound and performance. gle set of drawbars—I found a cool workaround. Simply create a “Favorite” (Hammond’s term for Keyboard Feel they’ll stand next to anything out there and not presets that save the entire state of the instru- I find that a 61-note keyboard is often too small leave you or the audience wanting for realism. -

The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 16, 2018, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters TODD BARKAN JOANNE BRACKEEN PAT METHENY DIANNE REEVES Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio and WPFW 89.3 FM. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 2 THE 2018 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts The 2018 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri and the Eddie Palmieri Sextet John Benitez Camilo Molina-Gaetán Jonathan Powell Ivan Renta Vicente “Little Johnny” Rivero Terri Lyne Carrington Nir Felder Sullivan Fortner James Francies Pasquale Grasso Gilad Hekselman Angélique Kidjo Christian McBride Camila Meza Cécile McLorin Salvant Antonio Sanchez Helen Sung Dan Wilson 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 -

The Vox Continental

Review: The Vox Continental ANDY BURTON · FEB 12, 2018 Reimagining a Sixties Icon The original Vox Continental, rst introduced by British manufacturer Jennings Musical Industries in 1962, is a classic “combo organ”. This sleek, transistor-based portable electric organ is deeply rooted in pop-music history, used by many of the biggest rock bands of the ’60’s and beyond. Two of the most prominent artists of the era to use a Continental as a main feature of their sound were the Doors (for example, on their classic 1967 breakthrough hit “Light My Fire”) and the Animals (“House Of The Rising Sun”). John Lennon famously played one live with the Beatles at the biggest-ever rock show to date, at New York’s Shea Stadium in 1965. The Continental was bright orange-red with reverse-color keys, which made it stand out visually, especially on television (which had recently transitioned from black-and-white to color). The sleek design, as much as the sound, made it the most popular combo organ of its time, rivaled only by the Farsa Compact series. The sound, generated by 12 transistor-based oscillators with octave-divider circuits, was thin and bright - piercing even. And decidedly low-delity and egalitarian. The classier, more lush-sounding and expensive Hammond B-3 / Leslie speaker combination eectively required a road crew to move around, ensuring that only acts with a big touring budget could aord to carry one. By contrast, the Continental and its combo- organ rivals were something any keyboard player in any band, famous or not, could use onstage. -

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975 History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page Inquire about purchasing the book (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Sound 1973-78 (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Borderline 1974-78 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. In the second half of the 1970s, Brian Eno, Larry Fast, Mickey Hart, Stomu Yamashta and many other musicians blurred the lines between rock and avantgarde. Brian Eno (34), ex-keyboardist for Roxy Music, changed the course of rock music at least three times. The experiment of fusing pop and electronics on Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy (sep 1974 - nov 1974) changed the very notion of what a "pop song" is. Eno took cheap melodies (the kind that are used at the music-hall, on television commercials, by nursery rhymes) and added a strong rhythmic base and counterpoint of synthesizer. The result was similar to the novelty numbers and the "bubblegum" music of the early 1960s, but it had the charisma of sheer post-modernist genius. Eno had invented meta-pop music: avantgarde music that employs elements of pop music. He continued the experiment on Another Green World (aug 1975 - sep 1975), but then changed its perspective on Before And After Science (? 1977 - dec 1977). Here Eno's catchy ditties acquired a sinister quality. -

Electric Organ Electric Organ Discharge

1050 Electric Organ return to the opposite pole of the source. This is 9. Zakon HH, Unguez GA (1999) Development and important in freshwater fish with water conductivity far regeneration of the electric organ. J exp Biol – below the conductivity of body fluids (usually below 202:1427 1434 μ μ 10. Westby GWM, Kirschbaum F (1978) Emergence and 100 S/cm for tropical freshwaters vs. 5,000 S/cm for development of the electric organ discharge in the body fluids, or, in resistivity terms, 10 kOhm × cm vs. mormyrid fish, Pollimyrus isidori. II. Replacement of 200 Ohm × cm, respectively) [4]. the larval by the adult discharge. J Comp Physiol A In strongly electric fish, impedance matching to the 127:45–59 surrounding water is especially obvious, both on a gross morphological level and also regarding membrane physiology. In freshwater fish, such as the South American strongly electric eel, there are only about 70 columns arranged in parallel, consisting of about 6,000 electrocytes each. Therefore, in this fish, it is the Electric Organ voltage that is maximized (500 V or more). In a marine environment, this would not be possible; here, it is the current that should be maximized. Accordingly, in Definition the strong electric rays, such as the Torpedo species, So far only electric fishes are known to possess electric there are many relatively short columns arranged in organs. In most cases myogenic organs generate electric parallel, yielding a low-voltage strong-current output. fields. Some fishes, like the electric eel, use strong – The number of columns is 500 1,000, the number fields for prey catching or to ward off predators, while of electrocytes per column about 1,000. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

Downbeat.Com March 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. DOWNBEAT.COM MARCH 2014 D O W N B E AT DIANNE REEVES /// LOU DONALDSON /// GEORGE COLLIGAN /// CRAIG HANDY /// JAZZ CAMP GUIDE MARCH 2014 March 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 3 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Kathleen Costanza Design Intern LoriAnne Nelson ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene -

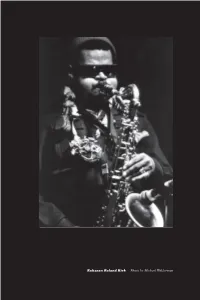

60 / Running Head

60 / running head RahsaRahsaaRahsaan Roland Kirk Photo by Michael Wilderman monstrosioso 1965: The Creeper The fussy encyclopedic gravity of the Hammond B-3 overcome and the electric organ lofted to hard-bop orbit, still trailing diapasons of his mother’s church music and the boogie-woogie tap-dance routines of his father’s band—The Incredible Jimmy Smith proclaimed the block letters on a score of albums since the 1956 breakout recordings on Blue Note, those words celebrating a nearly miraculous mating of technology and soul. The thing had first stirred to life at a club in Atlantic City where he heard Wild Bill Davis make the Hammond roar like a big wave. It was a monster, upsurged through chocked, choppy chords and backwashed through rilling legatos, wattage enough there to power the entire Basie band. Davis was gruff, brash, gloriously loud, a bumptious lumbering at- tack, great swoops down on the keys and shameless ripsaw goosings of reverb and tremolo, the organ not so much singing as signaling, the music stripped to pure swelling impulse. For a piano player schooled in the over- brimming muscular lines of Art Tatum and the stabbing, nervous prances of Bud Powell, it was almost risible, the goddamned wired-up thing rock- ing on stage like a gurgling showboat. Fats Waller on “Jitterbug Waltz” coaxed over the organ with a percolating finesse as if running a trapeze artist up a swaying wire, but Davis almost seemed clumsy by design, as if in awe of the organ’s powers yet unable to forego provoking them. -

Page 14 Street, Hudson, 715-386-8409 (3/16W)

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN THEATRE ORGAN SOCIETY NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2010 ATOS NovDec 52-6 H.indd 1 10/14/10 7:08 PM ANNOUNCING A NEW DVD TEACHING TOOL Do you sit at a theatre organ confused by the stoprail? Do you know it’s better to leave the 8' Tibia OUT of the left hand? Stumped by how to add more to your intros and endings? John Ferguson and Friends The Art of Playing Theatre Organ Learn about arranging, registration, intros and endings. From the simple basics all the way to the Circle of 5ths. Artist instructors — Allen Organ artists Jonas Nordwall, Lyn Order now and recieve Larsen, Jelani Eddington and special guest Simon Gledhill. a special bonus DVD! Allen artist Walt Strony will produce a special DVD lesson based on YOUR questions and topics! (Strony DVD ships separately in 2011.) Jonas Nordwall Lyn Larsen Jelani Eddington Simon Gledhill Recorded at Octave Hall at the Allen Organ headquarters in Macungie, Pennsylvania on the 4-manual STR-4 theatre organ and the 3-manual LL324Q theatre organ. More than 5-1/2 hours of valuable information — a value of over $300. These are lessons you can play over and over again to enhance your ability to play the theatre organ. It’s just like having these five great artists teaching right in your living room! Four-DVD package plus a bonus DVD from five of the world’s greatest players! Yours for just $149 plus $7 shipping. Order now using the insert or Marketplace order form in this issue. Order by December 7th to receive in time for Christmas! ATOS NovDec 52-6 H.indd 2 10/14/10 7:08 PM THEATRE ORGAN NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2010 Volume 52 | Number 6 Macy’s Grand Court organ FEATURES DEPARTMENTS My First Convention: 4 Vox Humana Trevor Dodd 12 4 Ciphers Amateur Theatre 13 Organist Winner 5 President’s Message ATOS Summer 6 Directors’ Corner Youth Camp 14 7 Vox Pops London’s Musical 8 News & Notes Museum On the Cover: The former Lowell 20 Ayars Wurlitzer, now in Greek Hall, 10 Professional Perspectives Macy’s Center City, Philadelphia.