SUSTAINING the NON-TIMBER FOREST PRODUCTS (Ntfps) BASED RURAL LIVELIHOODS of TRIBALS in JHARKHAND: ISSUES and CHALLENGES Sanjay Kr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr Cover October 7June 2010

9 Community Lift Irrigation Systems in Gumla District, Jharkhand RAKESH TIWARY Examining the irrigation sharing practices among beneficiary groups, their conflicts and conflict resolution mechanisms, the study identifies the scope for formal ans sustainable institutional mechanisms for community managed irrigation systems. This study was carried out for PRADAN, Ranchi and Jharkhand. INTRODUCTION In rural India, a large number of families depend on agriculture for food security and livelihood. Irrigation is most important for improving agricultural methods, output and productivity. Assured irrigation can substantially enhance livelihood opportunities, particularly for small and marginal farmers. In the tribal areas of eastern India, assured irrigation is most critical for making the shift from primitive and subsistence agriculture to modern and commercial agriculture. However, access to assured irrigation becomes much more difficult due to physiographic conditions, remoteness, poverty, lack of modern technology, etc. Hence, external assistance is extremely important to bridge the financial, technological, information and institutional gaps in the promotion of irrigation in these areas. In order to strengthen the existing livelihoods of the rural people in Jharkhand, Professional Assistance for Development Action (PRADAN) has undertaken the task of institutionalizing people-managed irrigation systems in the villages. These include wells in the homesteads, lowland wells, water lifting devices and river-based lift irrigation schemes. All such infrastructure was created through funding from different government programmes, specified for poor rural families. PRADAN provides techno-managerial support to install the systems and creates social organizations to manage the schemes in the long run. These systems are managed by groups of beneficiaries, who share the responsibility of meeting the operating costs, the maintenance and the safe-keep of the systems. -

Rural Empowerment Through Natural Resource Management

Title: Rural Empowerment by Natural Resource Management Topic of the case study: Strengthening village economy by replicable model of NRM Name of the researcher/ organisation: Dr.Elyas Majid, Dr.Seema Nath, Shramajivi Unnayan Thematic area of the case: The role of women SHGs empowered by GP and NGO coalition in bringing positive changes in agricultural sector using NRM-based government programmes Name of the Gram Panchayat, District, State: Shibrajpur Panchayat (Ghaghra Block), Gumla District, Jharkhand Abbreviation NRM Natural Resource Management PESA Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) FGD Focused Group Discussion HH HouseHold CBO Community Based Organization NGO Non-Government Organization PRI Panchayati Raj Institution ER Elected Representative SC Scheduled Caste ST Scheduled Tribe MFP Minor Forest Produce NRLM National Rural Livelihood Mission PRADAN Professional Assistance for Development Action APC Agriculture Production Cluster MGNREGS Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Gurantee Scheme SGSY Swarnajayanti Gram Swarozgar Yojana LGSS Lohardaga Gram Swarajya Sansthan Glossary Dobha Shallow water bodies Gram Pradhan Head of the village Gram Sabha Village council Gram Sangathan Village level association Mukhiya Village council chief Krishi Mitra Volunteer working for farmers’ welfare SGSY Government of India initiative to provide sustainable income to poorest of the poor people living in rural & urban areas of the country. Tola Hamlet Yojana Scheme Executive Summary A vast area of the state Jharkhand belongs to village and most of the people are dependent on rain-dependent farming, livestock rearing and collection of forest produces as their livelihood. But the farming practices and related infrastructures not being organised, it had never become a profitable way of earning. -

E-Procurement Notice

e-Procurement Cell JHARKHAND STATE BUILDING CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION LTD., RANCHI e-Procurement Notice Sr. Tender Work Name Amount in (Rs) Cost of Bids Completio No Reference BOQ (Rs) Security(Rs) n Time . No. Construction of 1 Model School in JSBCCL/2 Kunda Block of Chatra District of 1 3,16,93,052.00 10,000.00 6,33,900.00 15 months 0/2016-17 North Chotanagpur Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 1 Model School in JSBCCL/2 Tundi Block of Dhanbad District of 2 3,16,93,052.00 10,000.00 6,33,900.00 15 months 1/2016-17 North Chotanagpur Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 2 Model School in JSBCCL/2 Bagodar and Birni Block of Giridih 3 6,33,85,987.00 10,000.00 12,67,800.00 15 months 2/2016-17 District of North Chotanagpur Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 2 Model School in JSBCCL/2 Jainagar and Koderma Block of 4 6,33,85,987.00 10,000.00 12,67,800.00 15 months 3/2016-17 Koderma District of North Chotanagpur Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 2 Model School in JSBCCL/2 Boarijor and Sunder Pahari Block 5 6,33,85,987.00 10,000.00 12,67,800.00 15 months 4/2016-17 of Godda District of Santhal Pargana Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 1 Model School in JSBCCL/2 Amrapara Block of Pakur District 6 3,16,93,052.00 10,000.00 6,33,900.00 15 months 5/2016-17 of Santhal Pargana Division of Jharkhand. -

Ethnobotany of South Chotanagpur (Bihar)

BULL. BOT. SURV. INDIA Vol. 35. NOS. 1-4 : pp.40-59. 1993 ETHNOBOTANY OF SOUTH CHOTANAGPUR (BIHAR) A. K. SAHOOAND V. MUDGAL Botfiniccrl Survey of Indiu , Howruh ABSTRACT Ethnobotanical studies made among the tribals of Ranchi, Gumla, Lohardaga, Palamau districts of Bihar are presented. The paper provides uses of 146 plants for medicines, veterinary medicines. food, fodder. household, house building materials, various social and religious ceremonies. A comparison with the literature reveals that 42 uses of various plants reported in the present paper are new. Besides nine plant species reported to be used by the tribals of Chotanagpur for various purposes have not been mentioned in the earlier literature. INTRODUCTION 50% of the area. The general pattern of flora varies The districts of Ranchi , Gumla, Lohardaga and at different altitudes. The agricultural lands lies Palamau of south Chotanagpur division of Bihar is between the forest enclosure. situated between 22'-24' N latitude and 84'-86' E The forest of this region is tropical & moist longitude, guarded by West Bengal on east, deciduous type. Common trees in the forest are. Madhya Pradesh on west and Orissa on the south. Shorea robusta, Madhuca longifolia, Dalbergia The district of Hazaribagh Giridih and Dhanbad sisoo, Butea ntonosperrna, Sclzleicheru triguja, of north Chotanagpur division is distinct from Terminalia chehula, Senzecaryus anacardiunl, south Chotanagpur by its soil, climate and Svz~giunzcumini, Bllchat~anialatifoliu, 'Diospyros vegetation. The districts of south Chotanagpur exsculyra, Aditta cordifolia, Boswellia Serruta ; division have more forest area along with denser Cleistanthus collinus, Lagerstrdehtih ~p'&n,$ora'~, tribal population. The scope of ethnobotanical Acucia catechu etc. -

Ethnobotany of South Chotanagpur (Bihar)

BULL. BOT. SURV. INDIA Vol. 35. NOS. 1-4 : pp.40-59. 1993 ETHNOBOTANY OF SOUTH CHOTANAGPUR (BIHAR) A. K. SAHOOAND V. MUDGAL Botfiniccrl Survey of Indiu , Howruh ABSTRACT Ethnobotanical studies made among the tribals of Ranchi, Gumla, Lohardaga, Palamau districts of Bihar are presented. The paper provides uses of 146 plants for medicines, veterinary medicines. food, fodder. household, house building materials, various social and religious ceremonies. A comparison with the literature reveals that 42 uses of various plants reported in the present paper are new. Besides nine plant species reported to be used by the tribals of Chotanagpur for various purposes have not been mentioned in the earlier literature. INTRODUCTION 50% of the area. The general pattern of flora varies The districts of Ranchi , Gumla, Lohardaga and at different altitudes. The agricultural lands lies Palamau of south Chotanagpur division of Bihar is between the forest enclosure. situated between 22'-24' N latitude and 84'-86' E The forest of this region is tropical & moist longitude, guarded by West Bengal on east, deciduous type. Common trees in the forest are. Madhya Pradesh on west and Orissa on the south. Shorea robusta, Madhuca longifolia, Dalbergia The district of Hazaribagh Giridih and Dhanbad sisoo, Butea ntonosperrna, Sclzleicheru triguja, of north Chotanagpur division is distinct from Terminalia chehula, Senzecaryus anacardiunl, south Chotanagpur by its soil, climate and Svz~giunzcumini, Bllchat~anialatifoliu, 'Diospyros vegetation. The districts of south Chotanagpur exsculyra, Aditta cordifolia, Boswellia Serruta ; division have more forest area along with denser Cleistanthus collinus, Lagerstrdehtih ~p'&n,$ora'~, tribal population. The scope of ethnobotanical Acucia catechu etc. -

District Environment Plan of Gumla District

District Environment Plan of Gumla District Gumla Let’s make Green Gumla DISTRICT ADMINSTRATION 1 | P a g e District Environment Plan, Gumla. 2 | P a g e District Environment Plan, Gumla. INTRODUCTION Hon‘ble National Green Tribunal in O.A. No. 360/2018 dated: 26/09/2019 ordered regarding constitution of District Committee (as a part of District Planning Committee under Articles 243 ZD) under Articles 243 G, 243 W, 243 ZD read with Schedules 11 and 12 and Rule 15 of the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016. In the above said order, it is stated that among others ‘Chief Secretaries may personally monitor compliance of environmental norms (including BMW Rules) with the District Magistrate once every month. The District Magistrates may conduct such monitoring twice every month. We find it necessary to add that in view of Constitutional provisions under Articles 243 G, 243 W, 243 ZD read with Schedules 11 and 12 and Rule 15 of the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016 it is necessary to have a District Environment Plan to be operated by a District committee (as a part of District Planning Committee under Article 243 ZD) In this regard, Principal Secretary to Government Forest, Environment & Climate Change department vide letter no. 487 dated 07.02.2020, Special Secretary to Government Forest, Environment & Climate Change department vide letter no. 4869 dated 26.12.2019 and Deputy Secretary to Government Forest, Environment & Climate Change department vide letter no. 4871 dated 26.12.2019 and letter no. 1660 dated 24.06.2020 requested Member secretary of the District Environment committee to prepare District Environmental Plans. -

List of Safe, Semi-Critical,Critical,Saline And

Categorisation of Assessment Units State / UT District Name of Assessment Assessment Unit Category Area Type District / Unit Name GWRE Andaman & Nicobar Bampooka Island Bampooka Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Island Andaman & Nicobar Car Nicobar Island Car Nicobar Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Island Andaman & Nicobar Chowra Island Chowra Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & Nicobar Great Nicobar Island Great Nicobar Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Island Andaman & Nicobar Kamorta Island Kamorta Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & Nicobar Katchal Island Katchal Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & Nicobar Kondul Island Kondul Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & Nicobar Little Nicobar Island Little Nicobar Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Island Andaman & Nicobar Nancowrie Island Nancowrie Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Island Andaman & Nicobar Pilomilo Island Pilomilo Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & Nicobar Teressa Island Teressa Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & Nicobar Tillang-chang Island Tillang-chang Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Island Andaman & Nicobar Trinket Island Trinket Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Andaman & North & Aves Island Aves Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Middle Andaman & North & Bartang Island Bartang Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Middle Andaman & North & East Island East Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Middle Andaman & North & Interview Island Interview Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Middle Andaman & North & Long Island Long Island Safe Non-Notified Nicobar Middle Andaman & North & Middle -

Sarva Seva Samity Sanstha (4S)

Sarva Seva Samity Sanstha (4S) …… establishing sustainable and replicable models for uplifting the socio-economic status of poor and marginalized families Annual Report: 2018-19 Sarva Seva Samity Sanstha Sarva Seva Samity Sanstha (4S) Registered Office: Village + Post- Rajan, Gurua, Gaya- 824237, BIHAR Head Office: BG- 179, Salt Lake, Sector-II, Kolkata- 700 091, WEST BENGAL 1 Annual Report: 2018-19 Sarva Seva Samity Sanstha 2 Annual Report: 2018-19 Sarva Seva Samity Sanstha From the Desk of Executive Director he year 2018-19 is very special for Sarva Seva Samity Sanstha (4S), T as the organization has become sweet sixteen, grown rapidly and entered into another stage of maturity. The full year has been a year of experimentation, learning and evolving. The year threw-up many challenges that made us capable to handle the situation. We faced, we learned, we resolved…! But not a single situation could change our zeal of working for the favour of poor. The path was not been smooth, but we never gave a single scope to deviate ourselves from our vision. Rural poor and vulnerable community has always been at the centre of everything. And we believe that long lasting change at grassroots can only be brought with the active participation of the mass. We have now jumped into a team of 48 professionals from 14. The team is blessed with the continuous support of more than 150 volunteers working dedicatedly for social, financial and moral development of the society. We are delighted to have exceeded our targets in our all seventeen projects. We have strengthened and streamlined our intervention through regular monitoring, evaluation and strategic guidance. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Gumla District

2 Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 3-4 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 4-5 1.2 Topography 6 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 6-7 1.4 Forest 7 1.5 Administrative set up 7 2. District at a glance 7-10 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District of Gumla 10 3. Industrial Scenario Of Gumla District 10 3.1 Industry at a Glance 10 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 11 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 11-12 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 12 3.5 Major Exportable Item 12 3.6 Growth Trend 12-13 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 13 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 13 3.8.1 List of the units in Gumla District &nearby Area 13 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 13 3.9 Service Enterprises 13 3.9.1 Coaching Industry 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 13-14 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 14 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 15 4.1 Detail Of Major Clusters 15 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 15 4.1.2 Service Sector 15 4.2 Details of Identified cluster 15 5. General issues raised by industry association during the course of 15 meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 16 3 Brief Industrial Profile of Gumla District 1. General Characteristics of the District: During British rule Gumla was under Lohardaga district. In 1843 it was brought under Bishunpur province that was further named Ranchi. -

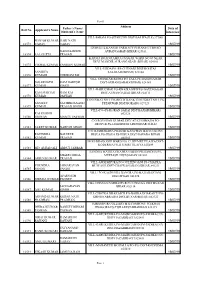

Roll No. Applicant's Name Address 16573 VILL

Sheet1 Address Father’s Name/ Date of Roll No. Applicant’s Name Husband’s Name Interview VILL-PARSIA PO-SITAKUND DIST-BALIYA(U.P) 277001 SHIVAM KUMAR HARI NATH 16573 YADAV YADAV 19/07/19 GURUKUL KANGRI FARMACY PURANI G.T.ROAD NAND KISHOR AURANGABAD BIHAR 824101 16574 LAL GUPTA PRASAD 19/07/19 KARMA ROAD RAMRAJ NAGAR WARD NO 07 NEAR DEVI MANDIR AURANGABAD (BIHAR) 824101 16575 VISHAL KUMAR SANJEEV KUMAR 19/07/19 VILL-URDA PO+PS-CHENARI DIST-ROHTAS SANGITA SASARAM(BIHAR) 821104 16576 KUMARI SHRIRAM PAL 19/07/19 VILL-SHANKAR BIGHA PO-SASA PS-DAUDNAGAR JAGARNATH RAM NARESH DIST-AURANGABAD(BIHAR) 824143 16577 KUMAR SINGH 19/07/19 VILL-HABUCHAK PO-KHAIRADWIP PS-DAUDNAGAR RAM SUBHAG RAM RAJ DIST-AURANGABAD BIHAR 824113 16578 KUMAR PASWAN 19/07/19 TENUGHAT NO 1 PO-RIGHT BANK TENUGHAT NO 1 PS- SANJEEV SACHHIDANAND PETARWAR DIST-BOKARO 829123 16579 KUMAR PRASAD SINGH 19/07/19 VILL+PO+PS-KORAN SARAI DIST-BAXAR(BIHAR) RAJ KISHOR 802126 16580 PASWAN MANTU PASWAN 19/07/19 C/O ROUSHAN KUMAR DEV AT KUSHMAHA PO- DEOPUR PS-JASIDIH DIST-DEOGHAR 814142 16581 SAKET KUMAR NARESH SINGH 19/07/19 C/O RAMRAKSHA PRASAD KANCHAN BAG COLONY RAVINDRA BALVEER HISUA PO-HISUA PS-HISUA DIST-NAVADA BIHAR 16582 KUMAR PRASAD 805103 19/07/19 MOH-BHADODIH WARD NO 17 JHUMRI TILAIYA DIST- KODERMA PO-JHUMRI TILAIYA 825409 16583 MD. AMJAD ALI ABDUL JABBAR 19/07/19 SANDHA MATHIA CHAPRA SARAN PO-SANDHA PS- SHATRUGHNA MUFFASIL DIST-SARAN 841301 16584 ARJUN KUMAR PRASAD 19/07/19 VILL-AWADHPURA PO-GULTENGANJ PS-CHAPRA VIJENDRA JAINARAYAN MUFFASIL DIST-CHAPRA(SARAN) BIHAR 841211 16585 -

Farm Innovations in Climate Resilient Agriculture

Farm Innovations in Climate Resilient Agriculture Ch Srinivasa Rao JVNS Prasad M Osman M Prabhakar BH Kumara AK Singh Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture Hyderabad Indian Council of Agricultural Research, New Delhi i Citation: Srinivasa Rao, Ch., Prasad, JVNS., Osman, M., Prabhakar, M., Kumara, BH., Singh, AK. 2017. Farm Innovations in Climate Resilient Agriculture. Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture, Hyderabad, 123 p. First Edition: 2017 Copies: 3000 All Rights Reserved ISBN Number: 978-93-8-80883-43-4 Technical Assistance CRIDA : Prasanna Kumar, Chandrashekhar, Shailesh Borkar, S Raghava Sharma, K Elisha ATARIs: Gopi Pannu, Diptanjay, Alicia Pasweth, Ajit Shrivastava, T Hima Bindu, Shyopal Ram Jat, Nitin Soni, Anita Published by The Director ICAR-Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture Santoshnagar, Hyderabad-500059 Ph: 040-24530177 Fax: 040-24531802 Website: http://www.crida.in E-mail: [email protected] Front Cover : Farm Innovations Back Cover : CRIDA Building Cover Pages Designed by: Mallesh Yadav, SSS Printed at: Heritage Print Service Pvt. Ltd. IDA, Uppal, Hyderabad - 500 039 Phone : 040-27201927, 27602453 ii PREFACE Climate change and climate variability are the major challenges for sustaining agricultural production in the country. There has been a significant rise in the frequency of extreme weather events in recent years affecting farm level productivity, threatening livelihoods particularly the small and marginal farmers in the vulnerable regions of the country. Farmers develop innovative solutions to face these challenges effectively drawing heavily from their experiences and the traditional wisdom. The drivers of the innovations are multifaceted in terms of economic, environmental, social and cultural factors wherein farmers may innovate out of necessity, adversity, opportunity and could be to improve the existing farming practices. -

Author's Name: Sanjay Kr. Verma Ph.D. Research Scholar in The

Author’s Name: Sanjay Kr. Verma Ph.D. Research Scholar in the Vishwa Bharati (a Central University) and Faculty of Rural Management Institutional Affiliation: Xavier Institute of Social Service Dr. Camil Bulcke Path, Ranchi: 834001, Jharkhand, India Email: [email protected] Cell: 09431350962 Title of the paper: Sustaining Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) Based Rural Livelihood of Tribal in Jharkhand: Issues and Challenges “ The author agree to allow the Digital Library of the Commons to add this paper to its archives for IASC conference”. 1 Sustaining Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) Based Rural Livelihood of Tribal in Jharkhand: Issues and Challenges Sanjay Kr. Verma i Dr. Sujit Kr. Paul ii Abstract Jharkhand literally means ‘forest region’ where forests play a central role in the economic, cultural and socio- political systems and the entire lives and livelihoods of a majority of the people revolve around forests and forestry. Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) play an important role in supporting rural livelihoods and food security in Jharkhand. The NTFPs have variable abundance according to season and the collection of these NTFPs record variations with the seasonal occupation of the local people. The present study tries to explore the spectrum of rural livelihood contributions of Non-Timber Forest Product (NTFP) to the tribals of Bishunpur block in Gumla district of Jharkhand state. However, the main objective is to assess and analyse the contribution of NTFPs to rural livelihood for both subsistence and commercial use and to identify factors influencing household level of engagement in the various cash incomes. For the present study two (2) villages were selected based on their proximity gradient from the forest.