The Influence of English on Croatian Hip-Hop Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zbornik Ob 20-Letnici MKK Bela Krajina

CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 061.2-053.6(497.4Črnomelj)(091) ALTERNATIVA na margini : 20 let MKK BK / [pisci člankov Igor Bašin ... [et al.] ; urednik, pisec spremne besede Janez Weiss ; fotografije Marko Pezdirc ... et al.]. - Črnomelj : Mladinski kulturni klub Bele krajine, 2010 1. Bašin, Igor 2. Weiss, Janez, 1978- 3. Mladinski kulturni klub Bele krajine (Črnomelj) 250618880 To ni eulogija, to ni epitaf! Konec najstni{ kih let. Hormonalne nestabilnosti so prebrodene in zdaj smo tu, v jutru dvajsetih, ponosni na dve desetletji dela, hkrati pa tudi želje po nadaljnjem delu, razvoju, rasti in novih zmagah. Dvajset let ne smemo pustiti mimo brez opisa, brez spomenika na{ emu trudu, delu in naivnostim. Zato smo se odlo~ ili zbrati prispevke, spomine, pisane in fotografirane, in jih obelodaniti, da ne bi v megli pozabe izginila na{{ a stremenja, na drobec k razvoju celote, tak { ne in druga~ ne, belokranjske, slovenske, evropske, globalne. Rad bi se zahvalil vsem, ki so brez nepotrebnega prepri~ evanja pristopili k projektu in pomagali pri njegovi realizaciji. Hvala Marku Zupani~{ u, Bo tjanu [ vajgerju, Heleni Vuk {~ ini , Robiju Lozarju, Du{{~ anu Jesihu, Samerju Khalilu, Igorju Ba inu, Branetu Koncilji, Goranu Jarnevi u, Juliju Karinu in Sa{~ u Jankovi u za besede ter Bo { tjanu Matja {~u i u, Mark Pezdircu, Tomu Urhu, Ireni Pov { e in Ga{~ perju Gregori u za foto utrinke. Poudariti moram, da klub nikakor ni le delo nas objavljenih tukaj, ravno obratno, je delo in prizadevanje kopice ljudi, ki so tokom dveh desetletij s svojo voluntersko in udarni{ ko voljo v najve~~i{{~~ ji meri omogo li obstanek in utrip na ega dru tva. -

Ice Cube Hello

Hello Ice Cube Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} The motherfuckin world is a ghetto Full of magazines, full clips, and heavy metal When the smoke settle.. .. I'm just lookin for a big yellow; in six inch stilletos Dr. Dre {Hello..} perculatin keep em waitin While you sittin here hatin, yo' bitch is hyperventilatin' Hopin that we penetratin, you gets natin cause I never been to Satan, for hardcore administratin Gangbang affiliatin; MC Ren'll have you wildin off a zone and a whole half a gallon {Get to dialin..} 9 1 1 emergency {And you can tell em..} It's my son he's hurtin me {And he's a felon..} On parole for robbery Ain't no coppin a plea, ain't no stoppin a G I'm in the 6 you got to hop in the 3, company monopoly You handle shit sloppily I drop a ki properly They call me the Don Dada Pop a collar, drop a dollar if you hear me you can holla Even rottweilers, follow, the Impala Wanna talk about this concrete? Nigga I'm a scholar The incredible, hetero-sexual, credible Beg a hoe, let it go, dick ain't edible Nigga ain't federal, I plan shit while you hand picked motherfuckers givin up transcripts Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} I started -

Razvoj Mrežne Stranice I Marketinške Strategije Za Hip Hop Glazbeni Projekt Rens

RAZVOJ MREŽNE STRANICE I MARKETINŠKE STRATEGIJE ZA HIP HOP GLAZBENI PROJEKT RENS Brčić, Lovro Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Algebra University College / Visoko učilište Algebra Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:225:721867 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-05 Repository / Repozitorij: Algebra Univerity College - Repository of Algebra Univerity College VISOKO UČILIŠTE ALGEBRA ZAVRŠNI RAD RAZVOJ MREŽNE STRANICE I MARKETINŠKE STRATEGIJE ZA HIP HOP GLAZBENI PROJEKT RENS Lovro Brčić Zagreb, siječanj 2020. „Pod punom odgovornošću pismeno potvrđujem da je ovo moj autorski rad čiji niti jedan dio nije nastao kopiranjem ili plagiranjem tuđeg sadržaja. Prilikom izrade rada koristio sam tuđe materijale navedene u popisu literature, ali nisam kopirao niti jedan njihov dio, osim citata za koje sam naveo autora i izvor, te ih jasno označio znakovima navodnika. U slučaju da se u bilo kojem trenutku dokaže suprotno, spreman sam snositi sve posljedice uključivo i poništenje javne isprave stečene dijelom i na temelju ovoga rada“. U Zagrebu, datum. Predgovor O odabiru teme za pisanje završnog rada nisam trebao puno razmišljati s obzirom na to da je glazba dio mog života već jako dugo. S obzirom na to da sam i sam dio jedne glazbene subkulture, uvijek me zanimalo kako promovirati tu vrstu glazbe da dođe do šire mase ljudi. Ovaj rad sadrži sve dosad naučeno o digitalnog marketingu. Zahvaljujem se mentoru mag. oec. Tomislavu Krištofu koji je pratio stvaranje ovog završnog rada te svojim savjetima i dostupnošću pomogao realizirati isti. Zahvaljujem se i svojoj obitelji na potpori tijekom studija i pisanja ovog rada. -

Trešnjevka U Očima Trešnjevčana Riječ Urednika

broj 40/41 jesen / zima 2017. BESPLATNO KVARTOVSKO GLASILO CEKATE: PROJEKT ABBA EUROPE KVARTOVSKA POVIJEST: SVI ŽIVOTI TREŠNJEVAČKIH ULIČNIH LOKALA POZNATI IZ SUSJEDSTVA: INTERVJU: KRISTIAN NOVAK IstražIvanje kvarta Trešnjevka u očima Trešnjevčana riječ urednika Dragi Trešnjevčani, Kao i uvijek u predblagdansko vrijeme donosimo vam novi broj s nizom zanimlji- vih tema o našem kvartu. Predstavljamo predsjednike vijeća grad- skih četvrti izabranih na prošlim lokal- nim izborima kao i predsjednike mjesnih odbora. Zanimali su nas planovi i prioriteti Novosti iz četvrti rada kao i ideje poboljšanja života. Sjećamo se i dvije posebno drage osobe koje su nas napustile. Naša kolegica Kri- stina Radošević je više od 20 godina radeći u Centru za kulturu Trešnjevka ostavila Idemo u veliki trag u nama i u samom Centru, a sje- ćamo se i dobrog duha Trešnjevke Zvonka CeKaTe Špišića i njegove „Trešnjevačke balade“. Naša četvrt je inspirativna studentima sociologije, donosimo istraživanje o identi- tetu kvarta. Informiramo vas i o novom por- Trešnjevačka posla talu koji bilježi ritam Trešnjevke. Posjetili smo i Gimnaziju u Dobojskoj koja svojim radom stalno donosi živost. I u CeKaTeu je dosta novosti – krenuo 2 je veliki međunarodni projekt a naš izlog Od 7 do 107 krase i pjesničko-slikarski radovi u okviru projekta „Prozor / prizor CeKaTea“. Spa- jamo pjesnike i likovne umjetnike i njihove posuđene radove izlažemo na mjesec dana poslije ekskluzivnog doručka s pjesnikom i slikarom za odabrane. Posjetili smo Dom za starije osobe Trešnjevka i vidjeli da je i tamo živo i zani- mljivo i da Grad na više načina skrbi o najugroženijim Trešnjevčanima. U intervju nam književnik Kristian Poznati iz susjedstva Novak otkriva kako je živjeti na Trešnjevci, a predstavljamo i okupljalište na Novoj cesti – klub No Sikiriki koji je već postao kultno mjesto u koji dolaze znatiželjnici iz svih dijelova grada „kako se ne bi sekirali“. -

Kelt Pub Karaoke Playlista SLO in EX-YU

Kelt pub Karaoke playlista SLO in EX-YU Colonia 1001 noc 25001 Oto Pestner 30 let 25002 Aerodrom Fratello 25066 Agropop Ti si moj soncek 25264 Aleksandar Mezek Siva pot 25228 Alen Vitasovic Gusti su gusti 25072 Alen Vitasovic Jenu noc 25095 Alen Vitasovic Ne moren bez nje 25163 Alfi Nipic Ostal bom muzikant 25187 Alfi Nipic Valcek s teboj 25279 Alka Vuica Lazi me 25118 Alka Vuica Otkad te nema 25190 Alka Vuica Profesionalka 25206 Alka Vuica Varalica 25280 Atomik Harmonik Brizgalna brizga 25021 Atomik Harmonik Hop Marinka 25079 Atomik Harmonik Kdo trka 25109 Azra A sta da radim 25006 Azra Balkan 25017 Azra Fa fa 25064 Azra Gracija 25071 Azra Lijepe zene prolaze kroz grad25123 Azra Pit i to je Amerika 25196 Azra Uzas je moja furka 25278 Bajaga 442 do Beograda 25004 Bajaga Dobro jutro dzezeri 25051 Bajaga Dvadeseti vek 25058 Bajaga Godine prolaze 25070 Bajaga Jos te volim 25097 Bajaga Moji drugovi 25148 Bajaga Montenegro 25149 Bajaga Na vrhovima prstiju 25154 Bajaga Plavi safir 25199 Bajaga Sa druge strane jastuka 25214 Bajaga Tamara 25253 Bajaga Ti se ljubis 25259 Bajaga Tisina 25268 Bajaga Zazmuri 25294 Bebop Ti si moje sonce 25266 Bijelo Dugme A ti me iznevjeri 25007 Bijelo dugme Ako ima Boga 25008 Bijelo dugme Bitanga i princeza 25019 Bijelo dugme Da mi je znati koji joj je vrag25033 Bijelo dugme Da sam pekar 25034 Bijelo Dugme Djurdjevdan 25049 Bijelo dugme Evo zaklet cu se 25063 Bijelo dugme Hajdemo u planine 25077 Bijelo dugme Ima neka tajna veza 25083 Bijelo dugme Jer kad ostari{ 25096 Bijelo dugme Kad zaboravis juli 25106 Bijelo -

HIGHLANDS NEWS-SUN Tuesday, August 20, 2019

HIGHLANDS NEWS-SUN Tuesday, August 20, 2019 VOL. 100 | NO. 232 | $1.00 YOUR HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER SINCE 1919 An Edition Of The Sun Student County arrested gets with gun FEMA at APHS money By KIM LEATHERMAN STAFF WRITER $4.35M received AVON PARK — Parents of Avon Park High School students received a call or saw a post By PHIL ATTINGER STAFF WRITER on social media that would make their heart skip a beat. A “weapon was discovered by SEBRING — County Administrator Randy Vosburg a Highlands County Sheriff’s PHIL ATTINGER/STAFF School Resource Deputy,” the confirmed Monday that FEMA post said. The following line Vehicles line up Monday morning on eastbound Sebring Parkway to turn off at Ben Eastman Road, a detour had sent the final $4.35 million said there was no threat to they will make for three to four months while the 90-degree turn is reshaped into a three-spoke, two-lane reimbursement for Hurricane students or the staff and was roundabout. Irma. meant to assuage fear. The “I have a check in my hand,” investigation is still ongoing. Vosburg said, noting that he had About 12:30 p.m. an anon- already handed it to the Clerk of ymous student told School the Courts for deposit into the Resource Deputy Jim Brimlow Parkway closed county’s bank that a 17 year-old male student accounts. had a gun. Officials with the Traffic rerouted 3-4 months to Lakeview Highlands Highlands County Sheriff’s said County com- the deputy had the suspect in By PHIL ATTINGER missioners had asked about custody within about three or STAFF WRITER four minutes. -

The Ultimate A-Z of Dog Names

Page 1 of 155 The ultimate A-Z of dog names To Barney For his infinite patience and perserverence in training me to be a model dog owner! And for introducing me to the joys of being a dog’s best friend. Please do not copy this book Richard Cussons has spent many many hours compiling this book. He alone is the copyright holder. He would very much appreciate it if you do not make this book available to others who have not paid for it. Thanks for your cooperation and understanding. Copywright 2004 by Richard Cussons. All rights reserved worldwide. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of Richard Cussons. Page 2 of 155 The ultimate A-Z of dog names Contents Contents The ultimate A-Z of dog names 4 How to choose the perfect name for your dog 5 All about dog names 7 The top 10 dog names 13 A-Z of 24,920 names for dogs 14 1,084 names for two dogs 131 99 names for three dogs 136 Even more doggie information 137 And finally… 138 Bonus Report – 2,514 dog names by country 139 Page 3 of 155 The ultimate A-Z of dog names The ultimate A-Z of dog names The ultimate A-Z of dog names Of all the domesticated animals around today, dogs are arguably the greatest of companions to man. -

Popular Music and Narratives of Identity in Croatia Since 1991

Popular music and narratives of identity in Croatia since 1991 Catherine Baker UCL I, Catherine Baker, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated / the thesis. UMI Number: U592565 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592565 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 Abstract This thesis employs historical, literary and anthropological methods to show how narratives of identity have been expressed in Croatia since 1991 (when Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia) through popular music and through talking about popular music. Since the beginning of the war in Croatia (1991-95) when the state media stimulated the production of popular music conveying appropriate narratives of national identity, Croatian popular music has been a site for the articulation of explicit national narratives of identity. The practice has continued into the present day, reflecting political and social change in Croatia (e.g. the growth of the war veterans lobby and protests against the Hague Tribunal). -

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc Number Disc Count Track Number Track Count Year Date Mod ified Date Added Bit Rate Sample Rate Volume Adjustment Kind Equalizer Comments Plays Last Played Skips Last Ski pped My Rating Abusadora (Dembow Remix by DJ O_D) Wisin & Yandel Perreo Reggaetón 4721754 196 2009 3/30/2011 9:12 P M 3/30/2011 9:48 PM 192 44100 MPEG audio file WWW.GOTDEMBOW.NET 174 6/11/2011 6:20 AM 5 Aiy-Eee Louisiana Pollywogs Louisiana Pollywogs - Louisiana Songs Fo r Kids Children's Music 2319451 231 1 1 17 17 1999 10/30/2010 6:58 PM 9/7/2010 3:59 PM 80 22050 MPEG audio file Cleaned by TuneUp! 9 5/2/2011 12:24 PM 1 11/3/2010 6:05 PM 100 Almost_Famous Eminem Recovery Hip-Hop 4685952 292 14 17 2010 8/28/2010 7:41 PM 9/7/2010 3:59 PM 128 44100 MPEG audio file www.Songgy.net 5 5/2/2011 12:20 P M 6 11/6/2010 1:39 PM Alwayz Into Somethin' N.W.A. Dr. Dre The Best Of N.W.A. Gangsta Rap 4324460 265 1 1 8 17 1991 10/30/2010 6:59 PM 9/7/2010 3:59 PM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Cleaned by TuneUp! 7 2/16/2011 12:08 PM 2 2/10/2011 12:51 PM Ameno (remix) Era Era [Limited Edition] 5476605 228 2 1998 7/31/2010 10:50 PM 9/7/2010 3:59 PM 192 44100 MPEG audio file 3 4/11/2011 7:55 PM 1 3/2/2011 11:04 AM Appetite For Destruction N.W.A. -

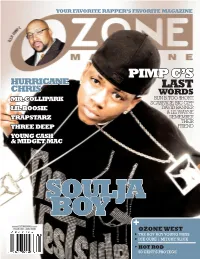

PIMP C’S HURRICANE LAST CHRIS WORDS MR

OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE PIMP C’S HURRICANE LAST CHRIS WORDS MR. COLLIPARK BUN B, TOO $HORT, SCARFACE, BIG GIPP LIL BOOSIE DAVID BANNER & LIL WAYNE REMEMBER TRILL N*GGAS DON’T DIE DON’T N*GGAS TRILL TRAPSTARZ THEIR THREE DEEP FRIEND YOUNG CASH & MIDGET MAC SOULJA BOY +OZONE WEST THE BOY BOY YOUNG MESS JANUARY 2008 ICE CUBE | MITCHY SLICK HOT ROD 50 CENT’S PROTEGE OZONE MAG // YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE PIMP C’S LAST WORDS SOULJA BUN B BOY TOO $HORT CRANKIN’ IT SCARFACE ALL THE WAY BIG GIPP TO THE BANK WITH DAVID BANNER MR. COLLIPARK LIL WAYNE FONSWORTH LIL BOOSIE’S BENTLEY JEWELRY CORY MO 8BALL & FASCINATION MORE TRAPSTARZ SHARE THEIR THREE DEEP FAVORITE MEMORIES OF THE YOUNG CASH SOUTH’S & MIDGET MAC FINEST HURRICANE CHRIS +OZONE WEST THE BOY BOY YOUNG MESS ICE CUBE | MITCHY SLICK HOT ROD 50 CENT’S PROTEGE 8 // OZONE WEST 2 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 8 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 0 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden features ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson 54-59 YEAR END AWARDS PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul 76-79 REMEMBERING PIMP C MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad Sr. 22-23 RAPPERS’ NEW YEARS RESOLUTIONS LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. 74 DIRTY THIRTY: PIMP C’S GREATEST HITS SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Adero Dawson ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Bogan, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, Cierra Middlebrooks, Destine Cajuste, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, K.G. -

3 Rap Subgenres

Jazyk černého britského a černého amerického rapu Bakalářská práce Studijní program: B7507 – Specializace v pedagogice Studijní obory: 7504R300 – Španělský jazyk se zaměřením na vzdělávání 7507R036 – Anglický jazyk se zaměřením na vzdělávání Autor práce: Jan Wolf Vedoucí práce: Christopher Muffett, M.A. Liberec 2019 The Language of Black British and Black American Rap Bachelor thesis Study programme: B7507 – Specialization in Pedagogy Study branches: 7504R300 – Spanish for Education 7507R036 – English for Education Author: Jan Wolf Supervisor: Christopher Muffett, M.A. Liberec 2019 Prohlášení Byl jsem seznámen s tím, že na mou bakalářskou práci se plně vzta- huje zákon č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, zejména § 60 – školní dílo. Beru na vědomí, že Technická univerzita v Liberci (TUL) nezasahuje do mých autorských práv užitím mé bakalářské práce pro vnitřní potřebu TUL. Užiji-li bakalářskou práci nebo poskytnu-li licenci k jejímu využití, jsem si vědom povinnosti informovat o této skutečnosti TUL; v tomto pří- padě má TUL právo ode mne požadovat úhradu nákladů, které vyna- ložila na vytvoření díla, až do jejich skutečné výše. Bakalářskou práci jsem vypracoval samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a na základě konzultací s vedoucím mé bakalářské práce a konzultantem. Současně čestně prohlašuji, že texty tištěné verze práce a elektronické verze práce vložené do IS STAG se shodují. 23. 6. 2019 Jan Wolf Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Christopher Muffett, M.A. for his advice, guidance and support. Also, I want to give thanks to my family for supporting me druing my studies. Lastly, I would like to show my appreciation to all the teachers at the English Department at the Faculty of Science, Humanities and Education of the Technical University in Liberec for allowing me to improve the level of my English. -

Problem Ne Leži U ACTA Sporazumu Ili U Autorskim Pravima, Već U Nereguliranom Internetskom Tržištu Glazbe Piše: Marina Ferić Jančić

STIPENDISTI FONDA MATZ / ROđENDANI SILVIJA FORETIćA I DUšANA PrašELJA / NOVE MUZIKOLOšKE SNAGE: AKTIVNOSTI FUsNOTE / IN MEMORIAM MARKO RUŽDJAK / RECENZIJE NOTNIH IZDANJA / CD IZLOG NOVINE HRVATSKOGA DRUŠTVA SKLADATELJA BROJ 173 OŽUJAK 2012. CIJENA 20 kn ISSN 1330–4747 Problem ne leži u ACTA sporazumu ili u autorskim pravima, već u nereguliranom internetskom tržištu glazbe Piše: Marina Ferić Jančić očetak veljače uvelike su obilje– Naime, svjesni činjenice da su gra– Pžila i događanja oko ACTA–e, đani željni kvalitetne i povoljne le– Međunarodnog trgovačkog spora– galne glazbene ponude, stupili smo zuma o borbi protiv krivotvorenja i u kontakt s međunarodnim glazbe– piratstva kojemu je pristupila i Eu– nim servisima s pitanjem zašto ih ropska unija, no koji u svojim naci– u našoj zemlji nema i pozivom da onalnim parlamentima nisu ratifici– dođu u Hrvatsku. rale neke zemlje članice Unije. Popularni iTunesi na naš su upit vrlo Pristupanje Unije sporazumu bilo je kratko odgovorili da zasad dola– povodom mnogih prosvjeda održa– zak u Hrvatsku nije u njihovu pla– nih diljem Europe, pa i u Hrvatskoj. nu. To je ujedno bio i jedini kontakt Mnogi prosvjednici i poneki politi– koji smo ikada s njima imali. Strea– čari, više ili manje upućeni, iznijeli ming servisi poput Spotify i Deezer s su ozbiljne kritike o mogućoj ugro– nama su više komunicirali te izrazi– ženosti ljudskih prava i građanskih li određeno zanimanje za dolaskom sloboda. Međutim, važno je raza– na ovo tržište. No, uz to su nezao– znati što je od svega izrečenog toč– bilazno išla