Contemporary Masters from Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Contemporary British Painting Prize Group Show 2016

The Contemporary British Painting Prize Group Show 2016 Seabrook Press The Contemporary British Painting Prize Group Show 2016 The Riverside Gallery, Richmond Museum, 10 September – 22 October Huddersfield Art Gallery, 5 November – 28 January “There can be no better, more sensitive or more serious way than 'The Contemporary British Painting Prize’ to discover and assess the exciting new directions being taken by painters in Britain today.” Michael Peppiatt, Art Critic and Curator, Paris “The Contemporary British Painting Prize offers us fresh and exciting perspectives on the new, dynamic and idiosyncratic trends being taken by painters in Britain right now.” Jessica Twyman, Director, Art Exchange “Although only in its first year, the Contemporary British Painting prize has drawn 631 entries of outstanding quality from both emerging and well-known artists and has set a benchmark for the nation.” Anna McNay, Art writer, London “It has been an amazing and rewarding experience for me to observe the creation and the evolution of Contemporary British Painting - as a concept, as an organisation and now as an award, the Contemporary British Painting Prize. The commitment and unfailing enthusiasm of Robert Priseman and his colleagues shown in the course of this evolution - all with the single purpose of re-establishing painting as the greatest and popular art medium in the contemporary art world - are truly impressive and deserving of praise. I've had the pleasure of reviewing the draft catalogue of the works of the Contemporary British Painting Award finalists and have been impressed by the depth of the subject matters and the variety of styles. -

A Comparative Analysis of Artist Prints and Print Collecting at the Imperial War Museum and Australian War M

Bold Impressions: A Comparative Analysis of Artist Prints and Print Collecting at the Imperial War Museum and Australian War Memorial Alexandra Fae Walton A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University, June 2017. © Copyright by Alexandra Fae Walton, 2017 DECLARATION PAGE I declare that this thesis has been composed solely by myself and that it has not been submitted, in whole or in part, in any previous application for a degree. Except where stated otherwise by reference or acknowledgement, the work presented is entirely my own. Acknowledgements I was inspired to write about the two print collections while working in the Art Section at the Australian War Memorial. The many striking and varied prints in that collection made me wonder about their place in that museum – it being such a special yet conservative institution in the minds of many Australians. The prints themselves always sustained my interest in the topic, but I was also fortunate to have guidance and assistance from a number of people during my research, and to make new friends. Firstly, I would like to say thank you to my supervisors: Dr Peter Londey who gave such helpful advice on all my chapters, and who saw me through the final year of the PhD; Dr Kylie Message who guided and supported me for the bulk of the project; Dr Caroline Turner who gave excellent feedback on chapters and my final oral presentation; and also Dr Sarah Scott and Roger Butler who gave good advice from a prints perspective. Thank you to Professor Joan Beaumont, Professor Helen Ennis and Professor Diane Davis from the Australian National University (ANU) for making the time to discuss my thesis with me, and for their advice. -

The Contemporary Art Society Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 1985 Tate Gallery 20 John Islip Street London SW1P4LL 01-82

The Contemporary Art Society Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 1985 Tate Gallery 20 John Islip Street London SW1P4LL 01-821 5323 The Annual General Meeting of The Contemporary Art Society will be held at the Warwick Arts Trust, 33 Warwick Square, London S.W.1. on Monday, 14 July, 1986, at 6.15pm. 1. To receive and adopt the report of the committee and the accounts for the year ended 31 December, 1985, together with the auditors'report. 2. To reappoint Neville Russeii as auditors of the Society in accordance with section 14 of the Companies Act, 1976, and to authorize the committee to • determine their remuneration for the coming year, 3. To elect to the committee the following who have been duly nominated: Sir Michael Culme-Seymour and Robin Woodhead. The retiring members are Alan Bowness and Belle Shenkman. 4. Any other business. By order of the committee Petronilla Silver Company Secretary 1 May, 1986 Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in London No. 255486 Charities Registration No. 208178 Cover: The Contemporary Art Society 1910-1985 Poster by Peter Blake {see back cover and inside lor details) Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother The CAS celebrated its 75th birthday this year. My report will be shorter than usual in order to allow space to print the speech made by Sir John Sainsbury when proposing the toast to the Society at. our birthday party at Christie's. Although, in fact, our Nancy Balfour OBE celebrations took place at the beginning of 1988, we felt an account rightly belonged in this year's report. -

David Hockney Selected Bibliography

DAVID HOCKNEY SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS AND EXHIBITION CATALOGUES 2018 David Hockney: Something New in Painting (and Photography) [and even Printing] (exhibition catalogue). Text by Lawrence Weschler. New York: Pace Gallery, 2018. Gayford, Martin. Modernists & Mavericks: Bacon, Freud, Hockney & The London Painters. London: Thames & Hudson, 2018. Modern British Art. London: Offer Waterman, 2018: 24–29, illustrated. Royal Academy of Arts 250th Summer Exhibition (exhibition catalogue). London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2018. 2017 The Art Museum. London: Phaidon, 2017: 407, illustrated. Booknesses: Artists’ Books from the Jack Ginsberg Collection (exhibition catalogue). Johannesburg, South Africa: University of Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017: 137, illustrated. David Hockney: The Exhibition (exhibition catalogue). Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2017. David Hockney (exhibition catalogue). Texts by Didier Ottinger, Chris Stephens, Marco Livingstone, et al. Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2017. David Hockney: Selected Bibliography—Books 2 David Hockney (exhibition catalogue). London: Tate Publishing, 2017. David Hockney: The Yosemite Suite (exhibition catalogue). Text by Alfred Pacquement. Paris: Galerie Lelong, 2017. Hockney, David. “David Hockney with William Corwin.” In Tell Me Something Good: Artist Interviews from The Brooklyn Rail. New York: David Zwirner Books, 2017: 204–210, illustrated. Kinsman, Jane. David Hockney Prints: The National Gallery of Australia Collection. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2017. Nippe, Christine and Christiane Wedemann. 50 Modern Artists You Should Know. Munich, London and New York: Prestel, 2017: 136–137, illustrated. UBS Art Collection: To Art Its Freedom. Text by Mary Rozell. Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag CmbH, 2016: 90, illustrated. 2016 Art at Work: The JPMorgan Chase Art Collection. Third edition. New York: JP Morgan Chase & Co., 2016: 307, illustrated. -

Stations Book

THE BRENTWOOD STATIONS OF THE CROSS Fifteen Stations of the Cross by fifteen contemporary painters First shown at Brentwood Cathedral, Ash Wednesday to Good Friday 2015 Copyright © 2015 Simon Carter, Father Martin Boland & all the contributing artists Designed and edited by Simon Carter All rights reserved ISBN-13: 978-1505832068 ISBN-10: 1505832063 THE BRENTWOOD STATIONS OF THE CROSS Project devised by Fr. Martin Boland Dean of Brentwood Cathedral INTRODUCTION: FAITH IN PAINT Simon Carter Being a believer within a protestant non-conformist tradition does not make it easy to be a painter. Non-conformists have traditionally had a marked mistrust of imagery and a firm attachment to words. We like the idea of Jesus as the Word of God (John 1:1) but are less keen on him as the Image of God (Colossians 1:15). For a painter a mistrust of images is anathema. In the early 1980’s Ruth and I visited the Nolde Foundation in North Germany and saw Nolde’s Life of Christ polyptych. I thought that to express my faith I would need to do something similar. There are moments and events in life that in retrospect assume unreasonable significance and it was the actual experience of visiting the Foundation that had a long after-life for me. We had cycled out of Denmark across flatlands of burnt stubble and drifting smoke. We were allowed to cross the border on a quiet back road as long as we promised to return the same day; the Foundation an isolated farmstead set among drainage dykes and a late summer flower garden. -

The Contemporary Art Society Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 1986 Tate Gallery 20 John Islip Street London SW1P 4LL 01-8

The Contemporary Art Society Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 1986 Tate Gallery 20 John Islip Street London SW1P 4LL 01-821 5323 The Annua! General Meeting of The Contemporary Art Society wiii be held at the Warwick Arts Trust, 33 Warwick Square, London S.W.1. on Monday, 13 July, 1987, at 6.15pm. 1. To receive and adopt the report of the committee and the accounts for the year ended 31 December, 1986, together with the auditors'report. 2. To reappoint Neville Russeii as auditors of the Society in accordance with section 14 of the Companies Act, 1976, and to authorize the committee to determine their remuneration for the coming year. 3. To elect to the committee the following who has been duly nominated: Richard Morphet. The retinng members are David Brown and William Packer. 4. Any other business. By order of the committee Petronilla Silver Company Secretary 1 May, 1987 Company Limited by Guarantee Registered In London No. 255486 Chanties Registration No. 208178 Cover: Cartoon by Michael Heath from 'The Independent' of 5 November, 1986 The 3rd Contemporary Art Society Market was held at Smith's Gallenes, Covent Garden, 5-8 November 1986 Sponsored by Sainsbury's, and Smith's Galleries Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother The most important event of the year, after our 75th birthday celebrations (which figured in our last Report), was the triennial Distribution show for which Christie's kindly lent us their Rooms. We opened the exhibition with a lunch for museum Balfour OBE directors and curators on 8 January. -

Contemporary Masters from Britain

Contemporary Masters From Britain 80 British Painters of the 21st Century Seabrook Press Contemporary Masters from Britain 80 British Painters of the 21st Century Jiangsu Arts and Crafts Museum Artall, Nanjing, China 10 to 23 October 2017 Seabrook Press David Ainley Iain Andrews Amanda Ansell Louis Appleby Richard Baker Claudia Böse Julian Brown Simon Burton Ruth Calland Emma Cameron Simon Carter Ben Cove Lucy Cox Andrew Crane Tony Casement Jules Clarke Jenny Creasy Pen Dalton Alan Davie Jeffrey Dennis Lisa Denyer Sam Douglas Annabel Dover Natalie Dowse Fiona Eastwood Nathan Eastwood Wendy Elia Tracey Emin Lucian Freud Paul Galyer Terry Greene Pippa Gatty Susan Gunn Susie Hamilton Alex Hanna David Hockney Marguerite Horner Barbara Howey Linda Ingham Silvie Jacobi Sue Kennington Anushka Kolthammer Matthew Krishanu Bryan Lavelle Cathy Lomax Clementine McGaw Paula MacArthur Lee Maelzer David Manley Enzo Marra Monica Metsers Michael Middleton Nicholas Middleton Andrew Munoz Keith Murdoch Stephen Newton Brian Lavelle Laura Leahy Kirsty O’Leary Leeson Gideon Pain Andrew Parkinson Mandy Payne Charley Peters Ruth Philo Alison Pilkington Robert Priseman Freya Purdue James Quin Greg Rook Katherine Russell Wendy Saunders Stephen Snoddy David Sullivan Harvey Taylor Delia Tournay-Godfrey Judith Tucker Julie Umerle Mary Webb Sean Williams Fionn Wilson 3 Freya Purdue’s Studio Isle of Wight, 2016 Susan Gunn In her studio, 2014 Contents Alphabetical Index of Artists 2 Introductory Essay by Robert Priseman 5 Notes 11 Works of Art New Realisms 13 New Abstractions -

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report 1987

The Contemporary Art Society Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 1987 Tate Gallery 20 John Islip Street London SW1P 4LL 01-821 5323 The Annual General Meeting of The Contemporary Art Society will be held at the Camden Arts Centre, Arkwright Road, London N.W.3. on Thursday, 21 July, 1988, at 6.30pm. 1. To receive and adopt the report of the committee and the accounts for the year ended 31 December, 1987, together with the auditors'report. 2. To reappoint Neville Russell as auditors of the Society in accordance with section 14 of the Companies Act, 1976, and to authorize the committee to determine their'remuneration for the coming year. 3. To elect to the committee the following who have been duly nominated: Robert Gumming, Rupert Gavin, Penelope Govett, Christina Smith, Adrian Ward-Jackson. The retiring members are Caryl Hubbard and Muriel Wilson. 4. Any other business. By order of the committee Petroniila Silver Company Secretary 1 May, 1988 Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in London No. 255486 Charities Registration No. 208178 Cover: A Short Memory to a Long Tail II 1986 concrete and paint by Zadok Ben-David purchased 1987 with the aid of a grant from the Henry Moore Foundation (cover sponsored by Benjamin Rhodes Gallery) Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother In 1987 the Society spent £112,000 on the purchase of work for gift to public galleries. This was a record amount, and represents an increase of over 100 per cent President over the last five years. This central fact will, we hope, assure members that we are Nancy Balfour OBE vigorously fulfilling our principal function. -

Read Stour Surrounding – Artists and the Valley Booklet

How this special landscape - of Constable, Gainsborough, Morris and Munnings - continues to shape and speak to contemporary artists today. A film produced by Jevan Watkins Jones ‘I’d been told that Wrabness was a special place and, when & Paul Press, Offshoot Foundation my partner (who has a caravan there) took me there for the first time, I caught a glimpse of the river from the winding road and I could see it was going to be magic. Simon Carter It came as a surprise to fall in love with an unfamiliar Desmond Brett Simon Carter is an artist and curator who was born in Essex in landscape. It is here that I feel a great connection to the Desmond Brett is a Senior Lecturer in BA (Hons) Fine Art 1961. He studied at Colchester Institute and North East London earth; the Stour, waiting for her tide to come in so we can (Sculpture). He previously worked as a Lecturer in Fine Art at Polytechnic. In 2013 he collaborated with artist Robert Priseman bathe, watching the baby jellyfish swimming early in the York St. John University and prior to that was Programme Leader to form the artist collective Contemporary British Painting and morning, the slippery mud of the shore, the dazzling mossy in Fine Art at Hull School of Art & Design. Desmond graduated also East Contemporary Art, a collection of contemporary art green marshes, the oaks blown by the wind, the big sky in from the Slade School of Fine Art, UCL, with a BA (Hons) Fine from the East of England, which is housed at the University of the day and the clarity of the constellations at night. -

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report 1979

The Annual General Meeting of the Contemporary Art Society will be held at Commercial Union Assurance, St Helen's, 1 Undershaft, London ECS on Thursday, June 19, 1980 at 6.45 p.m. To receive and adopt the report of the committee and the accounts for the year ended December 31,1979, together with the auditor's report. 2. To reappoint Sayers Butterworth as auditors of the society in accordance with section 14 of the Companies Act, 1976, and to authorize the committee to determine their remuneration for the coming year. 3. To elect to the committee the following who has been duly nominated: Lady Vaizey. The retiring members are Edward Lucie- Smith and Alistair McAipine. 4. Any other business. By order of the Committee Pauline Vogeipoe! May 19,1980 Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in London No 255486 Charities Registration No 208178 1 Patron Chairman's Report Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother In 1979 the Contemporary Art Society did once again what it was created in 1910 to do: it presented 135 works by 101 artists of today to 89 public Executive Committee art galleries in Great Britain and the Commonwealth. Nearly all these pictures and sculptures had been acquired during the previous four years, Nancy Balfour OBE Chairman some of them by gift or bequest but most of them by purchase with funds Alistair McAlpine Vice Chairman provided by subscriptions and donations from individual members, private Lord Croft Honorary Treasurer trusts, business firms and public galleries, supplemented by grants from Caryl Hubbard Honorary Secretary the Arts Councils of Great Britain and Scotland. -

Research Report | 2014 1

RESEARCH REPORT | 2014 1. INTRODUCTION 2014 was an exceptionally busy year for IWM. 19 July saw the opening of the innovative First World War Galleries and the redesigned atrium with new exhibitions and displays – all requiring intensive effort by historians and curators across IWM. The centrepiece of this major redevelopment work, the First World War Galleries, attracted almost one million visitors to IWM London in the first six months of opening alone. They drew on four years of research by a dedicated team of researchers who trawled IWM’s archives for especially engaging and historically illuminating material. The first year of the Centenary of the First World War had a huge and positive impact on IWM, and this was matched by intense activity in the higher education sector, to which IWM staff contributed in various ways. Success with funding bids, the presence of more PhD students and IWM’s closer involvement with the Consortium of National Museums, Galleries and Libraries with Independent Research Organisation status, demonstrated how our Research initiative was continuing to make headway. Suzanne Bardgett Head of Research A section of the new First World War Galleries at IWM London, formally opened on 17 July 2014. (IWM_SITE_LAM_003899) 1 2. COLLABORATIVE DOCTORAL AWARDS AND PhDs, AND SUCCESSFUL RESEARCH FUNDING BIDS 2.1. Collaborative Doctoral Partnership/Awards and IWM Supported PhDs IWM continued to benefit from the presence of several students working towards doctoral degrees, either as part of Collaborative Doctoral schemes or directly supported by IWM. Completed PhDs Christopher Deal was awarded his PhD by King’s College London in May 2014 after examination of his thesis Framing War, Sport and Politics: The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan and the Moscow Olympics. -

David Ainley

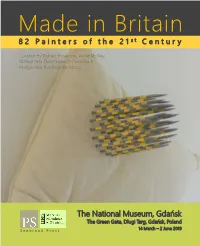

Made in Britain 82 Painters of the 21 st C e n t u r y Curated by Robert Priseman, Anna McNay, Małgorzata Taraszkiewicz-Zwolicka & Małgorzata Ruszkowska-Macur The National Museum, Gdańsk The Green Gate, Długi Targ, Gdańsk, Poland Seabrook Press 14 March – 2 June 2019 Made in Britain 82 Painters of the 21st Century Curated by Robert Priseman, Anna McNay, Małgorzata Taraszkiewicz-Zwolicka and Małgorzata Ruszkowska-Macur The National Museum, Gdańsk The Green Gate, Długi Targ 24, 80-828 Gdańsk, Poland Tel. + 48 58 307 59 12 Winter season: 1 October - 30 April Tuesday - Sunday 9.00 - 16.00 Summer season: 1 May - 30 September Tuesday - Sunday 10.00 - 17.00 14 March – 2 June 2019 David Ainley Iain Andrews Amanda Ansell Louis Appleby Richard Baker Karl Bielik Claudia Böse John Brennan Julian Brown Simon Burton Ruth Calland Emma Cameron Simon Carter Maria Chevska Jules Clarke Wayne Clough Ben Coode-Adams Ben Cove Lucy Cox Andrew Crane Pen Dalton Alan Davie Jeffrey Dennis Lisa Denyer Sam Douglas Annabel Dover Natalie Dowse Fiona Eastwood Nathan Eastwood Tracey Emin Geraint Evans Paul Galyer Pippa Gatty Terry Greene Susan Gunn Susie Hamilton Alex Hanna David Hockney Marguerite Horner Barbara Howey Phil Illingworth Linda Ingham Silvie Jacobi Kelly Jayne Matthew Krishanu Bryan Lavelle Andrew Litten Cathy Lomax Paula MacArthur David Manley Enzo Marra Monica Metsers Nicholas Middleton Andrew Munoz Keith Murdoch Paul Newman Stephen Newton Gideon Pain Andrew Parkinson Mandy Payne Charley Peters Ruth Philo Alison Pilkington Narbi Price Robert Priseman Freya