Stations Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Contemporary British Painting Prize Group Show 2016

The Contemporary British Painting Prize Group Show 2016 Seabrook Press The Contemporary British Painting Prize Group Show 2016 The Riverside Gallery, Richmond Museum, 10 September – 22 October Huddersfield Art Gallery, 5 November – 28 January “There can be no better, more sensitive or more serious way than 'The Contemporary British Painting Prize’ to discover and assess the exciting new directions being taken by painters in Britain today.” Michael Peppiatt, Art Critic and Curator, Paris “The Contemporary British Painting Prize offers us fresh and exciting perspectives on the new, dynamic and idiosyncratic trends being taken by painters in Britain right now.” Jessica Twyman, Director, Art Exchange “Although only in its first year, the Contemporary British Painting prize has drawn 631 entries of outstanding quality from both emerging and well-known artists and has set a benchmark for the nation.” Anna McNay, Art writer, London “It has been an amazing and rewarding experience for me to observe the creation and the evolution of Contemporary British Painting - as a concept, as an organisation and now as an award, the Contemporary British Painting Prize. The commitment and unfailing enthusiasm of Robert Priseman and his colleagues shown in the course of this evolution - all with the single purpose of re-establishing painting as the greatest and popular art medium in the contemporary art world - are truly impressive and deserving of praise. I've had the pleasure of reviewing the draft catalogue of the works of the Contemporary British Painting Award finalists and have been impressed by the depth of the subject matters and the variety of styles. -

Contemporary Masters from Britain

Contemporary Masters From Britain 85 British Painters of the 21st Century Seabrook Press Contemporary Masters from Britain 80 British Painters of the 21st Century Yantai Art Museum, Yantai 7 July–3 August Artall Gallery, Nanjing 10–23 October Jiangsu Art Museum, Nanjing 30 October–5 November Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts 1 December – 10 January China 2017 Seabrook Press David Ainley Iain Andrews Amanda Ansell Louis Appleby Richard Baker Karl Bielik Claudia Böse Day Bowman John Brennan Julian Brown Simon Burton Marco Cali Ruth Calland Emma Cameron Simon Carter Jules Clarke Ben Cove Lucy Cox Andrew Crane Pen Dalton Jeffrey Dennis Lisa Denyer Sam Douglas Annabel Dover Natalie Dowse Fiona Eastwood Nathan Eastwood Wendy Elia Geraint Evans Lucian Freud Paul Galyer Pippa Gatty Terry Greene Susan Gunn Susie Hamilton Alex Hanna David Hockney Marguerite Horner Barbara Howey Phil Illingworth Linda Ingham Matthew Krishanu Bryan Lavelle Laura Leahy Andrew Litten Cathy Lomax Clementine McGaw Paula MacArthur Lee Maelzer David Manley Enzo Marra Monica Metsers Nicholas Middleton Andrew Munoz Keith Murdoch Paul Newman Stephen Newton Gideon Pain Andrew Parkinson Mandy Payne Charley Peters Ruth Philo Barbara Pierson Alison Pilkington Robert Priseman Freya Purdue Greg Rook Katherine Russell Wendy Saunders Stephen Snoddy David Sullivan Harvey Taylor Ehryn Torrell Delia Tournay- Godfrey Judith Tucker Julie Umerle Mary Webb Rhonda Whitehead Sean Williams Fionn Wilson Julian Brown In his studio, London, 2013 Susan Gunn In her studio, 2014 Contents Alphabetical -

Contemporary Masters from Britain

Contemporary Masters From Britain 80 British Painters of the 21st Century Seabrook Press Contemporary Masters from Britain 80 British Painters of the 21st Century Jiangsu Arts and Crafts Museum Artall, Nanjing, China 10 to 23 October 2017 Seabrook Press David Ainley Iain Andrews Amanda Ansell Louis Appleby Richard Baker Claudia Böse Julian Brown Simon Burton Ruth Calland Emma Cameron Simon Carter Ben Cove Lucy Cox Andrew Crane Tony Casement Jules Clarke Jenny Creasy Pen Dalton Alan Davie Jeffrey Dennis Lisa Denyer Sam Douglas Annabel Dover Natalie Dowse Fiona Eastwood Nathan Eastwood Wendy Elia Tracey Emin Lucian Freud Paul Galyer Terry Greene Pippa Gatty Susan Gunn Susie Hamilton Alex Hanna David Hockney Marguerite Horner Barbara Howey Linda Ingham Silvie Jacobi Sue Kennington Anushka Kolthammer Matthew Krishanu Bryan Lavelle Cathy Lomax Clementine McGaw Paula MacArthur Lee Maelzer David Manley Enzo Marra Monica Metsers Michael Middleton Nicholas Middleton Andrew Munoz Keith Murdoch Stephen Newton Brian Lavelle Laura Leahy Kirsty O’Leary Leeson Gideon Pain Andrew Parkinson Mandy Payne Charley Peters Ruth Philo Alison Pilkington Robert Priseman Freya Purdue James Quin Greg Rook Katherine Russell Wendy Saunders Stephen Snoddy David Sullivan Harvey Taylor Delia Tournay-Godfrey Judith Tucker Julie Umerle Mary Webb Sean Williams Fionn Wilson 3 Freya Purdue’s Studio Isle of Wight, 2016 Susan Gunn In her studio, 2014 Contents Alphabetical Index of Artists 2 Introductory Essay by Robert Priseman 5 Notes 11 Works of Art New Realisms 13 New Abstractions -

Read Stour Surrounding – Artists and the Valley Booklet

How this special landscape - of Constable, Gainsborough, Morris and Munnings - continues to shape and speak to contemporary artists today. A film produced by Jevan Watkins Jones ‘I’d been told that Wrabness was a special place and, when & Paul Press, Offshoot Foundation my partner (who has a caravan there) took me there for the first time, I caught a glimpse of the river from the winding road and I could see it was going to be magic. Simon Carter It came as a surprise to fall in love with an unfamiliar Desmond Brett Simon Carter is an artist and curator who was born in Essex in landscape. It is here that I feel a great connection to the Desmond Brett is a Senior Lecturer in BA (Hons) Fine Art 1961. He studied at Colchester Institute and North East London earth; the Stour, waiting for her tide to come in so we can (Sculpture). He previously worked as a Lecturer in Fine Art at Polytechnic. In 2013 he collaborated with artist Robert Priseman bathe, watching the baby jellyfish swimming early in the York St. John University and prior to that was Programme Leader to form the artist collective Contemporary British Painting and morning, the slippery mud of the shore, the dazzling mossy in Fine Art at Hull School of Art & Design. Desmond graduated also East Contemporary Art, a collection of contemporary art green marshes, the oaks blown by the wind, the big sky in from the Slade School of Fine Art, UCL, with a BA (Hons) Fine from the East of England, which is housed at the University of the day and the clarity of the constellations at night. -

David Ainley

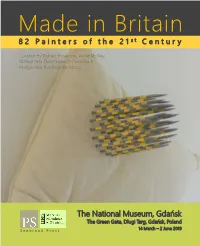

Made in Britain 82 Painters of the 21 st C e n t u r y Curated by Robert Priseman, Anna McNay, Małgorzata Taraszkiewicz-Zwolicka & Małgorzata Ruszkowska-Macur The National Museum, Gdańsk The Green Gate, Długi Targ, Gdańsk, Poland Seabrook Press 14 March – 2 June 2019 Made in Britain 82 Painters of the 21st Century Curated by Robert Priseman, Anna McNay, Małgorzata Taraszkiewicz-Zwolicka and Małgorzata Ruszkowska-Macur The National Museum, Gdańsk The Green Gate, Długi Targ 24, 80-828 Gdańsk, Poland Tel. + 48 58 307 59 12 Winter season: 1 October - 30 April Tuesday - Sunday 9.00 - 16.00 Summer season: 1 May - 30 September Tuesday - Sunday 10.00 - 17.00 14 March – 2 June 2019 David Ainley Iain Andrews Amanda Ansell Louis Appleby Richard Baker Karl Bielik Claudia Böse John Brennan Julian Brown Simon Burton Ruth Calland Emma Cameron Simon Carter Maria Chevska Jules Clarke Wayne Clough Ben Coode-Adams Ben Cove Lucy Cox Andrew Crane Pen Dalton Alan Davie Jeffrey Dennis Lisa Denyer Sam Douglas Annabel Dover Natalie Dowse Fiona Eastwood Nathan Eastwood Tracey Emin Geraint Evans Paul Galyer Pippa Gatty Terry Greene Susan Gunn Susie Hamilton Alex Hanna David Hockney Marguerite Horner Barbara Howey Phil Illingworth Linda Ingham Silvie Jacobi Kelly Jayne Matthew Krishanu Bryan Lavelle Andrew Litten Cathy Lomax Paula MacArthur David Manley Enzo Marra Monica Metsers Nicholas Middleton Andrew Munoz Keith Murdoch Paul Newman Stephen Newton Gideon Pain Andrew Parkinson Mandy Payne Charley Peters Ruth Philo Alison Pilkington Narbi Price Robert Priseman Freya -

Priseman Seabrook Collection of 21St Century British Painting

Priseman Seabrook Collection of 21st Century British Painting Seabrook Press Huddersfield Art Gallery 2014 Priseman Seabrook Collection of 21st Century British Painting Nathan Eastwood Bethnal Green, London, 2015 Contents Essay The Priseman Seabrook Collection of 21st Century British Painting by Robert Priseman 3 Notes 13 Sections Surrealism 15 Abstraction 51 New Realism 99 Alphabetical Index of Artists 152 Thanks Due 155 1 (Top) Gill Gibbon, Huddersfield Art Gallery Interview (Bottom) Installation view 2 2014 Essay 3 (Top) Installation view (Bottom) Artists and Curators Lunch 4 2014 The Priseman Seabrook Collection of 21st Century British Painting As a child, I used to sleep with a copy of John Constable’s painting ‘The Cornfield’ over my bed. And by day, regular family outings to see the Joseph Wright Collection at our local museum, the Derby Museum and Art Gallery, developed my own love of painting from an early age. My passion deepened as a student when I read Aesthetics and Art Theory at The University of Essex in the late 1980’s, a time when painting in Britain was experiencing one of its most exciting periods, with many exhibitions, books and magazines being published on the subject. It was the inspiration of this period which led me to take up painting myself, and in the summer of 2012 I was fortunate enough to co-curate the exhibition ‘Francis Bacon to Paula Rego’ at Abbot Hall Art Gallery with their Artistic Director Helen Watson. The aim of the show was simple – to revisit the landmark ‘School of London’ exhibition which Michael Peppiatt had curated in 1987 and see how painting had evolved in Britain during the intervening years. -

Priseman Seabrook Collection of 21St Century British Painting

Priseman Seabrook Collection of 21st Century British Painting 2015 Catalogue Robert Priseman Huddersfield Art Gallery 2014 Priseman Seabrook Collection of 21st Century British Painting (Top) Gill Gibbon, Huddersfield Art Gallery Interview, (Bottom) Installation view 2014 Essay (Top) Installation view, (Bottom) Artists and Curators Lunch 2014 The Priseman Seabrook Collection of 21st Century British Painting As a child, I used to sleep with a copy of John Constable’s painting ‘The Cornfield’ over my bed. And by day, regular family outings to see the Joseph Wright Collection at our local museum, the Derby Museum and Art Gallery, developed my own love of painting from an early age. My passion deepened as a student when I read Aesthetics and Art Theory at The University of Essex in the late 1980’s, a time when painting in Britain was experiencing one of its most exciting periods, with many exhibitions, books and magazines being published on the subject. It was the inspiration of this period which led me to take up painting myself, and in the summer of 2012 I was fortunate enough to co-curate the exhibition ‘Francis Bacon to Paula Rego’ at Abbot Hall Art Gallery with their Artistic Director Helen Watson. The aim of the show was simple – to revisit the landmark ‘School of London’ exhibition which Michael Peppiatt had curated in 1987 and see how painting had evolved in Britain during the intervening years. Michael’s original show had drawn together six of the leading British painters of the time. They were Michael Andrews, Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, R. -

The Aesthetics of De-Personalization, Professor Margaret Iversen, 2007 a Gallery of Ghosts' an Interview with the Painter Robert Priseman, Dr

Robert Priseman ______________________________________________________________________________________ Work in Museum Collections Australia Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney Austria Museum der Moderne Salzburg (11 works, ‘Nazi Gas Chambers: From Memory to History’) Belgium Musée de Louvain la Neuve China China Academy of Art, Hangzhou Jiangsu Arts and Crafts Museum, Nanjing Jiangsu Art Museum, Nanjing Tianjin Academy of Art, Tianjin Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts, Xi’an Yantai Art Museum, Yantai (3 works) Denmark Steno Museet, Aarhus Switzerland Museum der Universität Basel USA Allen Memorial Art Museum, Ohio Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Florida Dennos Museum Center, Michigan (15 works, from ‘Fame’) Denison Museum, Ohio (12 works, ‘Freaks’) Dittrick Museum, Cleveland, Ohio FSU MoFA, Florida (36 works, ‘Outlaws’) Guggenheim, New York (artist book) Honolulu Museum of Art, Hawaii The Mabee-Gerrer Museum of Art, Oklahoma Madison Museum of Fine Art, Georgia The Mead Art Museum, Massachusetts (17 works, ‘No Human Way to Kill’) Schneider Museum of Art, Oregon Tweed Museum of Art, Minnesota (15 works, ‘The Wannsee Portraits’) UAMA, Arizona (71 works, ‘Fame’) UMMA, Michigan Wayne State University Art Collection, Michigan Westmont Ridley-Tree Museum of Art, California (5 works, ‘SUMAC’) UK Abbot Hall Art Gallery Derby Museums and Art Gallery East Contemporary Art Collection (2 works) Falmouth Art Gallery Hertford Museum Huddersfield Art Gallery MOMA Wales Rugby Art Gallery and Museum (2 works) Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art Swindon Museum