The Devils' Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wendy A. Woloson. Refined Tastes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth‐Century America

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons College of the Pacific aF culty Articles All Faculty Scholarship Spring 1-1-2003 Wendy A. Woloson. Refined aT stes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth‐Century America Ken Albala University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles Part of the Food Security Commons, History Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Albala, K. (2003). Wendy A. Woloson. Refined Tastes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth‐Century America. Winterthur Portfolio, 38(1), 72–76. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles/70 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the All Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of the Pacific aF culty Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72 Winterthur Portfolio 38:1 upon American material life, the articles pri- ture, anthropologists, and sociologists as well as marily address objects and individuals within the food historians. It also serves as a vivid account Delaware River valley. Philadelphia, New Jersey, of the emergence of consumer culture in gen- and Delaware are treated extensively. Outlying eral, focusing on the democratization of once- Quaker communities, such as those in New En- expensive sweets due to new technologies and in- gland, North Carolina, and New York state, are es- dustrial production and their shift from symbols sentially absent from the study. Similarly, the vol- of power and status to indulgent ephemera best ume focuses overwhelmingly upon the material life left to women and children. -

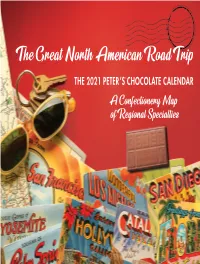

A Confectionery Map of Regional Specialties

The Great North American Road Trip THE 2021 PETER’S® CHOCOLATE CALENDAR A Confectionery Map of Regional Specialties One of the great pleasures of domestic travel in North America is to see, hear and taste the regional differences that characterize us. The places where we live help shape the way we think, the way we talk and even the way we eat. So, while chocolate has always been one of the world’s great passions, the ways in which we indulge that passion vary widely from region to region. In this, our 2021 Peter’s Chocolate Calendar, we’re celebrating the great love affair between North Americans and chocolate in all its different shapes, sizes, and flavors. We hope you’ll join us on this journey and feel inspired to recreate some of the specialties we’ve collected along the way. Whether it’s catfish or country-fried steak, boiled crawfish or peach cobbler, Alabama cuisine is simply divine. Classic southern recipes are as highly prized as family heirlooms and passed down through the generations in the Cotton State. This is doubtless how the confection known as Southern Divinity built its longstanding legacy in this region. The balanced combination of salty and sweet is both heavenly and distinctly Southern. Southern Divinity Southern Divinity Sun Mon Tue Wed Thur Fri Sat Ingredients: December February 1 001 2 002 2 Egg Whites S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 17 oz Sugar 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 56 6 oz Light Corn Syrup 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 4 oz Water 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 1 tbsp Vanilla Extract 27 28 29 30 31 28 New Year’s Day 6 oz Coarsely Chopped Pecans, roasted & salted Peter’s® Marbella™ Bittersweet Chocolate, 003 004 005 006 007 008 009 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 for drizzling Directions: Beat egg whites in a stand mixer until stiff National Chocolate peaks form. -

CENTRAL EURASIAN STUDIES REVIEW (CESR) Is a Publication of the Central Eurasian Studies Society (CESS)

The CENTRAL EURASIAN STUDIES REVIEW (CESR) is a publication of the Central Eurasian Studies Society (CESS). CESR is a scholarly review of research, resources, events, publications and developments in scholarship and teaching on Central Eurasia. The Review appears two times annually (Winter and Summer) beginning with Volume 4 (2005) and is distributed free of charge to dues paying members of CESS. It is available by subscription at a rate of $50 per year to institutions within North America and $65 outside North America. The Review is also available to all interested readers via the web. Guidelines for Contributors are available via the web at http://cess.fas.harvard.edu/CESR.html. Central Eurasian Studies Review Editorial Board Chief Editor: Marianne Kamp (Laramie, Wyo., USA) Section Editors: Perspectives: Robert M. Cutler (Ottawa/Montreal, Canada) Research Reports: Jamilya Ukudeeva (Aptos, Calif., USA) Reviews and Abstracts: Shoshana Keller (Clinton, N.Y., USA), Philippe Forêt (Zurich, Switzerland) Conferences and Lecture Series: Payam Foroughi (Salt Lake City, Utah, USA) Educational Resources and Developments: Daniel C. Waugh (Seattle, Wash., USA) Editors-at-Large: Ali Iğmen (Seattle, Wash., USA), Morgan Liu (Cambridge, Mass., USA), Sebastien Peyrouse (Washington, D.C., USA) English Language Style Editor: Helen Faller (Philadelphia, Penn., USA) Production Editor: Sada Aksartova (Tokyo, Japan) Web Editor: Paola Raffetta (Buenos Aires, Argentina) Editorial and Production Consultant: John Schoeberlein (Cambridge, Mass., USA) Manuscripts and related correspondence should be addressed to the appropriate section editors: Perspectives: R. Cutler, rmc alum.mit.edu; Research Reports: J. Ukudeeva, jaukudee cabrillo.edu; Reviews and Abstracts: S. Keller, skeller hamilton.edu; Conferences and Lecture Series: P. -

The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games

© Copyright 2019 Terrence E. Schenold The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games Terrence E. Schenold A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Brian M. Reed, Chair Leroy F. Searle Phillip S. Thurtle Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English University of Washington Abstract The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games Terrence E. Schenold Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Brian Reed, Professor English The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games explores the complex relationship between digital games and the activity of reflection in the context of the contemporary media ecology. The general aim of the project is to create a critical perspective on digital games that recovers aesthetic concerns for game studies, thereby enabling new discussions of their significance as mediations of thought and perception. The arguments advanced about digital games draw on philosophical aesthetics, media theory, and game studies to develop a critical perspective on gameplay as an aesthetic experience, enabling analysis of how particular games strategically educe and organize reflective modes of thought and perception by design, and do so for the purposes of generating meaning and supporting expressive or artistic goals beyond amusement. The project also provides critical discussion of two important contexts relevant to understanding the significance of this poetic strategy in the field of digital games: the dynamics of the contemporary media ecology, and the technological and cultural forces informing game design thinking in the ludic century. The project begins with a critique of limiting conceptions of gameplay in game studies grounded in a close reading of Bethesda's Morrowind, arguing for a new a "phaneroscopical perspective" that accounts for the significance of a "noematic" layer in the gameplay experience that accounts for dynamics of player reflection on diegetic information and its integral relation to ergodic activity. -

1 Primal Love

1 PRIMAL LOVE The heart breaks in so many different ways that when it heals, it will have faultlines. John Geddes As babies, our very survival depends on the fulfillment of a primal dream I call the ‘bliss dream’. It’s one of raw, sensual connection and soul-to-soul love where everything else is secondary. When the dream is unrequited or simply imperfect, loss and disappointment can cut faultlines of anxiety, lack of self-worth or gaping emotional hunger in a developing heart. Even those who suffer little incur some losses as they grow – having to share parents with siblings, feeling pain, experiencing inevitable separations. Everyone has faultlines. It’s part of being human. Some faultlines are deeper, more far-reaching or jagged than others. Over time our faultlines are made raw, broken and etched deeper by stormy emotional weather; in other seasons their edges are smoothed or even hardened by our various experiences. Our early experiences influence how we see the world. Our brains unconsciously start to map out the potential paths we will choose, the kinds of people we will be attracted to and the emotional lessons and reparations we will feel drawn to seek. From birth to death we define and traverse our Lovelands – our inner landscape of intimacy, passions and losses. It’s through love that we pursue our most primal needs: the need to belong, the need for security, the need for a home, for sensual desires and the search for purpose and pleasure. All our reasons to exist live there. Love is the pure elemental energy of life. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

ED353829.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 353 829 FL 020 927 AUTHOR Ismatulla, Khayrulla; Clark, Larry TITLE Uzbek: Language Competencies for Peace Corps Volunteers in Uzbekistan. INSTITUTION Peace Corps, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Jul 92 NOTE 215p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Instructional Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Alphabets; Classroom Communication; Competency Based Education; Cultural Context; Cultural Traits; *Daily Living Skills; Dialogs (Language); Family Life; Food; Foreign Countries; Government (Administrative Body); *Grammar; Independent Study; *Intercultural Communication; Job Skills; Monetary Systems; Non Roman Scripts; Phonology; *Pronunciation; Public Agencies; Transportation; *Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Uzbek; Vocabulary Development; Volunteer Training IDENTIFIERS Peace Corps; *Uzbekistan ABSTRACT This text is designed for classroom and self-study of Uzbek by Peace Corps volunteers training to serve in Uzbekistan. It consists of language and culture lessons on 11 topics: personal identification; classroom communication; conversation with hosts; food; getting and giving directions; public transportation; social situations; the communications system; medical needs; shopping; and speaking about the Peace Corps. An introductory section outlines major phonological and grammatical characteristics of the Uzbek language and features of the Cyrillic alphabet. Subsequent sections contain the language lessons, organized by topic and introduced with cultural notes. Each lesson consists of a prescribed competency, a brief dialogue, vocabulary list, and notes on grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and spelling. Appended materials include: a list of the competencies in English and further information on days of the week, months, and seasons, numerals and fractions, forms of addess, and kinship terms. A glossary of words in the dialogues is also included. (MSE) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

A Narrative Approach to the Philosophical Interpretation Of

A NARRATIVE APPROACH TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL INTERPRETATION OF DREAMS, MEMORIES, AND REFLECTIONS OF THE UNCONSCIOUS THROUGH THE USE OF AUTOETHNOGRAPHY/BIOGRAPHY A Dissertation by ANTONIO RIVERA ROSADO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: Curriculum and Instruction A NARRATIVE APPROACH TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL INTERPRETATION OF DREAMS, MEMORIES, AND REFLECTIONS OF THE UNCONSCIOUS THROUGH THE USE OF AUTOETHNOGRAPHY/BIOGRAPHY A Dissertation by ANTONIO RIVERA ROSADO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Co-Chairs of Committee, Stephen Carpenter Patrick Slattery Committee Members, Valerie Hill-Jackson Toby Egan Head of Department, Dennie Smith May 2011 Major Subject: Curriculum and Instruction iii ABSTRACT A Narrative Approach to the Philosophical Interpretation of Dreams, Memories, and Reflections of the Unconscious Through the Use of Autoethnography/Biography. (May 2011) Antonio Rivera Rosado, B.A., Interamerican University of Puerto Rico; M.Ed., The University of Texas at El Paso Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee, Dr. Stephen Carpenter Dr. Patrick Slattery The purpose of the present study aimed to develop a comprehensive model that measures the autoethnographic/biographic relevance of dreams, memories, and reflections as they relate to understanding the self and others. A dream, memory, and reflection (DMR) ten item questionnaire was constructed using aspects of Freudian, Jungian, and Lacanian Theory of Dream Interpretation. Fifteen dreams, five memories, and five reflections were collected from the participant at the waking episode or during a moment of deep thought. -

Philology UDC 811.512.133 Mamashaeva Mastura Mamasolievna Senior Teacher Namangan State University Mamashaev Muzaffar Abdumalik

Іntеrnаtіоnаl Scіеntіfіc Jоurnаl “Іntеrnаukа” http://www.іntеr-nаukа.cоm/ Philology UDC 811.512.133 Mamashaeva Mastura Mamasolievna Senior Teacher Namangan State University Mamashaev Muzaffar Abdumalikovich Teacher Namangan Institute of Civil Engineering Soliyeva Makhfuza Mamasolievna Teacher of the School No. 11 in Uychi District MASHRAB THROUGH THE EYES OF GERMAN ORIENTALIST MARTIN HARTMAN Summary. In this article we will study the heritage of the poet Boborahim Mashrab in Germany, in particular by the German orientalist Martin Hartmann. Key words: Shah Mashrab, a world-renowned scientist, "Wonderful dervish or saintly atheist", "King Mashrab", "Devoni Mashrab". After gaining independence, our people have a growing interest in learning about their country, their language, culture, values and history. This is natural. There are people who want to know their ancestors, their ancestry, the history of their native village, city, and finally their homeland. Today the world recognizes that our homeland is one of the cradles of not only the East but also of the world civilization. From this ancient and blessed soil, great scientists, scholars, scholars, commanders were born. The foundations of religious and secular sciences have been created and adorned on this earth.Thousands of manuscripts, including the history, literature, art, politics, Іntеrnаtіоnаl Scіеntіfіc Jоurnаl “Іntеrnаukа” http://www.іntеr-nаukа.cоm/ Іntеrnаtіоnаl Scіеntіfіc Jоurnаl “Іntеrnаukа” http://www.іntеr-nаukа.cоm/ ethics, philosophy, medicine, mathematics, physics, chemistry, astronomy, architecture, and agriculture, from the earliest surviving manuscripts, to records, are stored in our libraries. the works are our enormous spiritual wealth and pride. Such a legacy is rare in the world. The time has come for the careful study of these rare manuscripts, which combine the centuries-old experience of our ancestors, with their religious, moral and scientific views. -

RESULT of ENTRANCE TEST for ADMISSION to PRIVATE and PUBLIC SECTOR MEDICAL and DENTAL COLLEGES 2011 ID No

RESULT OF ENTRANCE TEST FOR ADMISSION TO PRIVATE AND PUBLIC SECTOR MEDICAL AND DENTAL COLLEGES 2011 ID No. NAME FATHER NAME MARKS 00001 KARESHMA WALI SHER WALI 116 00002 KASHIF ULLAH HAKEEM KHAN 194 00003 MUHAMMAD NAEEM MUHAMMED ILYAS 88 00004 TAZA GUL JANAN KHAN 394 00005 SHEEMA IQBAL MUHAMMAD IQBAL 30 00006 AMIR JAMAL NOOR JAMAL 73 00007 GOHAR JAMAL NOOR JAMAL 35 00008 RAHEEL ZAMAN SHAH ZAMAN 437 00009 SAMRINA KHAN PROF. DR. AMIR KHAN 189 00010 SIKANDAR IQBAL MUHAMMAD TAHIR 320 00011 MEHRUNISA KHAN KHALIL AURANGZEB KHAN KHALIL 395 00012 KARIM ULLAH SARFARAZ KHAN 244 00013 SUMAYYA SADIQ HAJI SADIQ SHAH 221 00014 SYED SEBGHAT ULLAH SAHIBZADA 123 00015 NAZISH YOUSAF YOUSAF ALI 120 00016 NAILA IJAZ IJAZ HUSSAIN 273 00017 NADIA ZAIB JEHAN ZAIB KHAN 75 00018 MAHREEN GOHAR GOHAR DIN 115 00019 ANAM ULLAH MUZAMMIL KHAN 419 00020 MARIA NIZAM NIZAM UD DIN 360 00021 MUJHAMMAD BASIT MUSHTAQ HUSSAIN 378 00022 UZMA MUSHRAZULLAH 89 00023 IJAZ ULLAH BAKHT SULTAN 27 00024 HAMID KHAN MUHAMMAD AFZAL 367 00025 ANEES KHAN MUHAMMAD KHAN 187 00026 ASIF KAMAL ABDUL MAJEEB 436 00027 ASIF ULLAH FAIZ ULLAH 70 00028 UMAR HAYAT BAKHTAWAR SHAH 429 00029 SHEHZADI UMBREEN EID BADSHAH 232 00030 BILAL AHMAD YAR MUHAMMAD 79 00031 SAMEERA TAJ BAHADAR 202 00032 AMJAD HAMEED ABDUL HAMEED KHAN 20 00033 ZEESHAN KAMIL KHAN 232 00034 NAJMUL ALAM SHAH DAD KHAN 228 00035 ALMAS RANI NABI REHMAT 314 00036 IQRA NAWAZ MUHAMMAD NAWAZ 344 00037 MUHAMMAD ASAD ALI SHAUKAT ALI 218 00038 AYESHA ZAIB JEHANZAIB 424 00039 IZHAR UL HAQ GUL SALAM KHAN 104 00040 MIDRARULLAH KHAN MOHAMMAD ALI