1 Primal Love

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Devils' Dance

THE DEVILS’ DANCE TRANSLATED BY THE DEVILS’ DANCE HAMID ISMAILOV DONALD RAYFIELD TILTED AXIS PRESS POEMS TRANSLATED BY JOHN FARNDON The Devils’ Dance جينلر بازمي The jinn (often spelled djinn) are demonic creatures (the word means ‘hidden from the senses’), imagined by the Arabs to exist long before the emergence of Islam, as a supernatural pre-human race which still interferes with, and sometimes destroys human lives, although magicians and fortunate adventurers, such as Aladdin, may be able to control them. Together with angels and humans, the jinn are the sapient creatures of the world. The jinn entered Iranian mythology (they may even stem from Old Iranian jaini, wicked female demons, or Aramaic ginaye, who were degraded pagan gods). In any case, the jinn enthralled Uzbek imagination. In the 1930s, Stalin’s secret police, inveigling, torturing and then executing Uzbekistan’s writers and scholars, seemed to their victims to be the latest incarnation of the jinn. The word bazm, however, has different origins: an old Iranian word, found in pre-Islamic Manichaean texts, and even in what little we know of the language of the Parthians, it originally meant ‘a meal’. Then it expanded to ‘festivities’, and now, in Iran, Pakistan and Uzbekistan, it implies a riotous party with food, drink, song, poetry and, above all, dance, as unfettered and enjoyable as Islam permits. I buried inside me the spark of love, Deep in the canyons of my brain. Yet the spark burned fiercely on And inflicted endless pain. When I heard ‘Be happy’ in calls to prayer It struck me as an evil lure. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

EDITORIAL May 18, 2017 Online at for IMMEDIATE RELEASE

EDITORIAL May 18, 2017 Online at www.proedtn.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MOTHER’S DAY SUMMARY Mother’s Day is a day of celebration. Saying something bad about someone’s Mother’s Day is a day of mother is usually grounds for a fight. Even hardened criminals love their mom. celebration. This Mother’s Day, When a mother looks at her newborn child it is perhaps the purest love ever known. appreciate the woman Many authors throughout the centuries have expanded upon this subject for deeper you call Mom, Mama, or meaning in their works. For example, Ezekiel 16:4 says, “As is the mother, so is her Mother and reflect upon daughter.” Poet, Ralph Waldo Emerson also wrote, “Men are what their mothers the true meaning of a made them.” Lastly, Edgar Allen Poe wrote, “Because I feel that, in the Heavens mother. above / The angels, whispering to one another, / Can find, among their burning terms of love / None so devotional as that of ‘Mother.’” On Mother’s Day, we get to honor our first best friend and the person you can always turn to when you need guidance. The influence of a mother in the lives of her children is well beyond calculation. Mothers hold their child’s hand for a fleeting moment, but they remain in their hearts forever. In the words of American novelist, Gail Tsukiyama, “Mothers and their children are in a category all their own. There’s no bond so strong in the entire world. No love so instantaneous and forgiving.” We are probably unaware of the unseen contributions a mother has in each one of our lives. -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

Chandler Knows Rap

Chandler Knows Rap 1. The speaker of a song titled for these people proclaims that he will “throw it in the gutter and go buy another” after he wrapped his car “‘round the telephone pole.” Another song titled for these people has an Eminem reference in its line “they money slim, they actin’ shady.” A song titled for this group of people features the artist shooting his friend JD after catching him trying to steal an Alpine speaker. A single titled for these people was the first release of (*) Ruthless Records. The artist of a song titled for these people raps “do it just like Nicki gon’ (go on) and bend it over / Say she never smoked I turned her to a stoner.” The chorus of a song titled for these people contains the line “don’t quote me boy, ‘cause I ain’t said shit.” A popular 2014 song titled for this group of people repeats the refrain “hol’ up.” For 10 points, what group of people which title a Wiz Khalifa song are “always hard” according to an Eazy E song? ANSWER: the boyz [accept “We Dem Boyz” or “Boyz-n-the-Hood”] 2. This EP’s title track describes the artist snorting adderall during “an episode out in Hollywood, / wilin’ out like Nick Cannon.” The artist of this mixtape analogized the breakup of his former group Kids These Days to a “C section.” It’s not by Biggie, but a song on this EP repeats the refrain “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, fuck 12,” and is about the murder of Laquan McDonald. -

Jesus Had One Day Left on Earth and He…Washed Feet

WEEK 1: Jesus had one day left on earth and He…washed feet I recently received a WhatsApp message on a Sunday school group that I belong to – our youth worker likes to send encouraging snippets or food for thought, to us group mentors on a weekly basis. This particular message was a quote which read: “Sometimes I joke about what I’d do if I had one day left to live. Eat whatever I want to, do something crazy, etc. Today it hit me: Jesus knew. …and He washed feet”. Being sceptical about such quotes, I immediately did some research online, just to confirm the details for myself…and yes, Jesus indeed washed the feet of His disciples the night before the day of his trials and crucifixion – at the last supper (John 13: 1-12). To me it’s amazing to think that Jesus, amidst the anxiety and turmoil in His heart knowing what lay ahead of Him, chose to serve His disciples in such an intimate way. But, the washing of their feet wasn’t enough for Jesus, after this He withdrew to a quiet place and prayed for His disciples (John 17: 1-26). It becomes clear that Jesus REALLY cared for His disciples and that His ministry legacy REALLY mattered to Him. The following questions come to mind: Do I REALLY love my neighbour? Does my legacy REALLY matter to me? To what extent am I willing to serve my neighbour, even in my hour of turmoil? In the coming weeks, I’ll spend some time on the theme: LOVE, and why it matters. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

Lil Wayne Feat Eminem No Love Lyrics

Lil wayne feat eminem no love lyrics No Love Lyrics: Love, love / Love, love, love / Don't hurt me / Don't hurt me no more, no more / Love / Throw dirt on me and [Hook: Eminem and Lil Wayne]. Lyrics to "No Love" song by Eminem: Love. Don't hurt me. Don't hurt Eminem Lyrics. "No Love" (feat. Lil Wayne). Love. Don't hurt me. Don't hurt me. No more. View the Lil Wayne lyrics for the song No Love with Eminem. Lyrics to 'No Love' by Eminem: All about my dough but I don't even check the peephole So you can keep knocking but won't knock me down No love lost, No love. Lyrics for No Love by Eminem feat. Lil Wayne. Love Love Love Don't hurt me Don't hurt me No more Young Money, yeah Uh, throw dirt on me. Lyrics for No Love (explicit) by Eminem feat. Lil Wayne. Young Money, yeah Throw dirt on me and grow a wildflower But it's fuck the world, get a. No Love Songtext von Eminem feat. Lil Wayne mit Lyrics, deutscher Übersetzung, Musik-Videos und Liedtexten kostenlos auf No Love (clean) Songtext von Eminem feat. Lil Wayne mit Lyrics, deutscher Übersetzung, Musik-Videos und Liedtexten kostenlos auf Lyrics of NO LOVE by Eminem feat. Lil Wayne: Verse 2 Eminem, I'm alive again more alive than I have been in my whole entire life, I can see. Videoklip, překlad a text písně No love ft. Lil Wayne od Eminem. [Hook - Eminem & Lil Wayne] It's a little too late to say that you're sorry now You kicked. -

Introduction to the Romans Project Page 5: Memorizing Schedule Pages 6-23: the Romans Project Verse Cards

The Romans Project Page 1: The Romans Project Cut-Out Cover Pages 2-4: Introduction to The Romans Project Page 5: Memorizing Schedule Pages 6-23: The Romans Project Verse Cards © 2012 annvoskamp.com 2 Why make time to Memorize God’s Word? In the age of Google, who makes time to still memorize God? Past generations made it a priority to memorize God’s Word. Are we now losing a way of life… and losing our way? In our making to-do lists to run our lives, why not make time to let God’s Word revolutionize our lives? Because making time to memorize His Word is putting first things first. If we fail to keep His Word in mind, we may simply fail. "What a heart knows by heart is what a heart really knows," urges Dennis Lennon. And what the heart knows by heart is all that can calm the heart. And direct the heart. And strengthen the heart. What do our hearts really know? Will we who claim to be believers of the Word commit to shaping our lives with His Letters? Committing the Holy to heart is the way we commune with the Holy Himself. Scripture repetition is the way we daily revive our faith, the slow pumping of the Word of Life into the lungs with the breath of His Words. And for the disciples of Christ, this Scripture Memorization isn't a one-time hurtle — but a life-long habit. A way of living to live the Way of Christ. We want this to be a discipline we practice for the rest of our lives. -

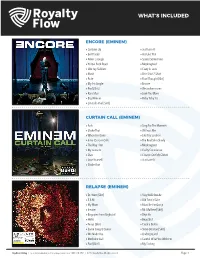

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. -

The Black Vernacular Versus a Cracker's Knack for Verses

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Arts Arts Research & Publications 2014-10-24 The black vernacular versus a cracker's knack for verses Flynn, Darin McFarland Books Flynn, D. (2014). The black vernacular versus a cracker's knack for verses. In S. F. Parker (Ed.). Eminem and Rap, Poetry, Race: Essays (pp. 65-88). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112323 book part "Eminem and Rap, Poetry, Race: Essays" © 2014 Edited by Scott F. Parker Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca The Black Vernacular Versus a Cracker’s Knack for Verses Darin Flynn Who would have ever thought that one of the greatest rappers of all would be a white cat? —Ice-T, Something from Nothing: The Art of Rap1 Slim Shady’s psychopathy is worthy of a good slasher movie. The soci- olinguistics and psycholinguistics behind Marshall Mathers and his music, though, are deserving of a PBS documentary. Eminem capitalizes on his lin- guistic genie with as much savvy as he does on his alter egos. He “flips the linguistics,” as he boasts in “Fast Lane” from Bad Meets Evil’s 2011 album Hell: The Sequel. As its title suggests, this essay focuses initially on the fact that rap is deeply rooted in black English, relating this to Eminem in the context of much information on the language of (Detroit) blacks. This linguistic excur- sion may not endear me to readers who hate grammar (or to impatient fans), but it ultimately helps to understand how Eminem and hip hop managed to adopt each other. -

Sweet 16 Hot List

Sweet 16 Hot List Song Artist Happy Pharrell Best Day of My Life American Authors Run Run Run Talk Dirty to Me Jason Derulo Timber Pitbull Demons & Radioactive Imagine Dragons Dark Horse Katy Perry Find You Zedd Pumping Blood NoNoNo Animals Martin Garrix Empire State of Mind Jay Z The Monster Eminem Blurred Lines We found Love Rihanna/Calvin Love Me Again John Newman Dare You Hardwell Don't Say Goodnight Hot Chella Rae All Night Icona Pop Wild Heart The Vamps Tennis Court & Royals Lorde Songs by Coldplay Counting Stars One Republic Get Lucky Daft punk Sexy Back Justin Timberland Ain't it Fun Paramore City of Angels 30 Seconds Walking on a Dream Empire of the Sun If I loose Myself One Republic (w/Allesso mix) Every Teardrop is a Waterfall mix Coldplay & Swedish Mafia Hey Ho The Lumineers Turbulence Laidback Luke Steve Aoki Lil Jon Pursuit of Happiness Steve Aoki Heads will roll Yeah yeah yeah's A-trak remix Mercy Kanye West Crazy in love Beyonce and Jay-z Pop that Rick Ross, Lil Wayne, Drake Reason Nervo & Hook N Sling All night longer Sammy Adams Timber Ke$ha, Pitbull Alive Krewella Teach me how to dougie Cali Swag District Aye ladies Travis Porter #GETITRIGHT Miley Cyrus We can't stop Miley Cyrus Lip gloss Lil mama Turn down for what Laidback Luke Get low Lil Jon Shots LMFAO We found love Rihanna Hypnotize Biggie Smalls Scream and Shout Cupid Shuffle Wobble Hips Don’t Lie Sexy and I know it International Love Whistle Best Love Song Chris Brown Single Ladies Danza Kuduro Can’t Hold Us Kiss You One direction Don’t You worry Child Don’t