The Black Vernacular Versus a Cracker's Knack for Verses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Columbia Chronicle (05/21/2001) Columbia College Chicago

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Chronicle College Publications 5-21-2001 Columbia Chronicle (05/21/2001) Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle Part of the Journalism Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Chronicle (05/21/2001)" (May 21, 2001). Columbia Chronicle, College Publications, College Archives & Special Collections, Columbia College Chicago. http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle/514 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Chronicle by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. Sport~ECEIVED The Chocolate Turner Cup bound Messiah resurrects Nt.~· 2 :'! 2001 COLVMJJ!A ·,... Back Pc€')LLEGE LmRA}fy; Internet cheating creates mixed views But now students are finding By Christine Layous new ways to help ease their Staff Writer workload by buying papers o fT the Internet. "Plagiarism is a serious To make it easier for stu offense and is not, by any dents, there are Web sites that means, c<,mdoned or encour offer papers for a price. aged by Genius Papers." Geniuspapers.com was even A disclaimer with that mes featured on the search engine sage would be taken serious. Yahoo. They offer access to but how seriously when it term papers written by stu comes from an Internet site dents for a subscription of only that's selling term papers? $9.95 a year. -

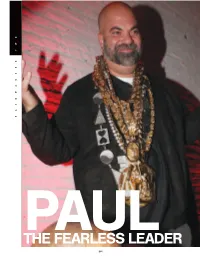

The Fearless Leader Fearless the Paul 196

TWO RAINMAKERS PAUL THE FEARLESS LEADER 196 ven back then, I was taking on far too many jobs,” Def Jam Chairman Paul Rosenberg recalls of his early career. As the longtime man- Eager of Eminem, Rosenberg has been a substantial player in the unfolding of the ‘‘ modern era and the dominance of hip-hop in the last two decades. His work in that capacity naturally positioned him to seize the reins at the major label that brought rap to the mainstream. Before he began managing the best- selling rapper of all time, Rosenberg was an attorney, hustling in Detroit and New York but always intimately connected with the Detroit rap scene. Later on, he was a boutique-label owner, film producer and, finally, major-label boss. The success he’s had thus far required savvy and finesse, no question. But it’s been Rosenberg’s fearlessness and commitment to breaking barriers that have secured him this high perch. (And given his imposing height, Rosenberg’s perch is higher than average.) “PAUL HAS Legendary exec and Interscope co-found- er Jimmy Iovine summed up Rosenberg’s INCREDIBLE unique qualifications while simultaneously INSTINCTS assessing the State of the Biz: “Bringing AND A REAL Paul in as an entrepreneur is a good idea, COMMITMENT and they should bring in more—because TO ARTISTRY. in order to get the record business really HE’S SEEN healthy, it’s going to take risks and it’s going to take thinking outside of the box,” he FIRSTHAND told us. “At its height, the business was run THE UNBELIEV- primarily by entrepreneurs who either sold ABLE RESULTS their businesses or stayed—Ahmet Ertegun, THAT COME David Geffen, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert FROM ALLOW- were all entrepreneurs.” ING ARTISTS He grew up in the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, surrounded on all sides TO BE THEM- by music and the arts. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

28 September 2003 CHART #1377 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums STAND UP ROCK YOUR BODY THIRTEENTH STEP THE 88 1 Scribe 21 Justin Timberlake 1 A Perfect Circle 21 Minuit Last week 1 / 9 weeks Gold / DIRTY/FMR Last week 28 / 16 weeks Gold / BMG Last week 0 / 1 weeks VIRGIN/EMI Last week 30 / 3 weeks TARDUS / UNIVERSAL WHERE IS THE LOVE? BROTHAZ PURE DIAMONDS ON THE INSIDE 2 Black Eyed Peas 22 Nesian Mystik 2 Hayley Westenra 22 Ben Harper Last week 2 / 15 weeks UNIVERSAL Last week 41 / 2 weeks BOUNCE/UNIVERSAL Last week 1 / 9 weeks Platinum x2 / UNIVERSAL Last week 16 / 28 weeks Platinum x2 / VIRGIN/EMI SHAKE YA TAILFEATHER WHITE FLAG BAD BOYS 2 SOUNDTRACK ELEPHANT 3 Nelly / P.Diddy / Murphy Lee 23 Dido 3 Soundtrack 23 The White Stripes Last week 3 / 3 weeks UNIVERSAL Last week 21 / 8 weeks BMG Last week 4 / 3 weeks UNIVERSAL Last week 20 / 25 weeks Gold / SHOCK/BMG RIGHT THURR RUBBERNECKIN (PAUL OAKENFO... MICHAEL BUBLE THE VERY BEST OF 4 Chingy 24 Elvis Presley 4 Michael Buble 24 George Benson Last week 4 / 3 weeks CAPITOL/EMI Last week 24 / 2 weeks BMG Last week 3 / 3 weeks Gold / WARNER Last week 15 / 8 weeks Gold / WARNER SENORITA U MAKE ME WANNA ONE DROP EAST Riverhead 5 Justin Timberlake 25 Blue 5 Salmonella Dub 25 Goldenhorse Last week 6 / 4 weeks BMG Last week 26 / 12 weeks VIRGIN/EMI Last week 2 / 5 weeks Gold / VIRGIN/EMI Last week 24 / 22 weeks Gold / SIREN/EMI BETTER PHLEX LOVE AND DISRESPECT DANGEROUSLY IN LOVE 6 Brooke Fraser 26 Blindspott 6 Elemeno P 26 Beyonce Knowles Last week 5 / 13 weeks SONY Last week 20 / 17 weeks Gold -

DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince I Think I Can Beat Mike

D.J. Jazzy Jeff And The Fresh Prince I Think I Can Beat Mike Tyson mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: I Think I Can Beat Mike Tyson Country: US Released: 1989 MP3 version RAR size: 1790 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1468 mb WMA version RAR size: 1773 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 757 Other Formats: AIFF DXD AC3 WAV MOD AHX AU Tracklist Hide Credits I Think I Can Beat Mike Tyson (Extended Remix) A1 7:06 Remix – Def Geoff Hunt* I Think I Can Beat Mike Tyson (Radio Mix) A2 4:56 Remix – Def Geoff Hunt* A3 I Think I Can Beat Mike Tyson (Instrumental) 4:56 I Think I Can Beat Mike Tyson (LP Version) B1 4:46 Remix – Def Geoff Hunt* Jeff Waz On The Beat Box (Extended Remix) B2 5:10 Remix – D.J. Jazzy Jeff*, Joe "The Butcher" Nicolo B3 Jeff Waz On The Beat Box (Instrumental) 5:39 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Compass Point Studios Recorded At – Kajem/Victory Studios — Victory East, Philadelphia, PA Mixed At – Kajem/Victory Studios — Victory East, Philadelphia, PA Credits Engineer – D.J. Jazzy Jeff*, Nigel Green Mixed By – D.J. Jazzy Jeff*, Nigel Green Producer – D.J. Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince*, Nigel Green, Pete Q. Harris Notes Recorded at Compass Point Studios. The Bahamas and Kajem Victory. Philadelphia PA. Mixed at Kajem Victory. Philadelphia PA. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year D.J. Jazzy Jeff JIVET 225, JIVE I Think I Can Beat Jive, JIVET 225, JIVE UK & And The Fresh 1989 T 225 Mike Tyson (12") Jive T 225 Europe Prince* D.J. -

God Loves Ugly

"This Minneapolis indie rap hero has potential to spare, delivering taut, complex rhyme narratives with everyman earnestness." -ROLLING STONE STREET DATE: 1.20.09 ATMOSPHERE GOD LOVES UGLY Repackaged, remastered and uglier than ever, the critically acclaimed third official studio release from Atmosphere, God Loves Ugly, is back after being out of print for over a year. The God Loves RSE-0031 Ugly re-issue also features a FREE bonus DVD. Format: CD+DVD / 2LP+DVD Packaging: Digi-Pak Originally released as the limited Sad Clown Bad Box Lot: 30 File Under: Rap/Hip Hop “A” Dub 4 (The Godlovesugly Release Parties) DVD, Parental Advisory: Yes it features 2 hours of live performance footage, Street Date: 1.20.09 backstage shenanigans, several special guest appearances and music videos for “Godlovesugly”, CD-826257003126 LP-826257003119 “Summersong” and “Say Shh”. Out of print +26257-AADBCg +26257-AADBBj for years, this DVD has been repackaged in a custom sleeve that comes inserted in with the re-issue of God Loves Ugly. TRACKLISTING: 1. ONEMOSPHERE 2. THE BASS AND THE MOVEMENT SELLING POINTS: 3. GIVE ME •Produced by Ant (Atmosphere, Brother Ali, Felt, etc.) 4. F*@CK YOU LUCY God Loves Ugly has scanned over 174,000 RTD. 5. HAIR • 6. GODLOVESUGLY •Catalog sales history of over a million units. 7. A SONG ABOUT A FRIEND •Current release When Life Gives You Lemons, You Paint 8. FLESH That Shit Gold scanned 36,526 in it’s first week and 9. SAVES THE DAY 10. LOVELIFE debuted #5 on the Billboard Top 200. 11. BREATHING 12. -

Eminem Interview Download

Eminem interview download LINK TO DOWNLOAD UPDATE 9/14 - PART 4 OUT NOW. Eminem sat down with Sway for an exclusive interview for his tenth studio album, Kamikaze. Stream/download Kamikaze HERE.. Part 4. Download eminem-interview mp3 – Lost In London (Hosted By DJ Exclusive) of Eminem - renuzap.podarokideal.ru Eminem X-Posed: The Interview Song Download- Listen Eminem X-Posed: The Interview MP3 song online free. Play Eminem X-Posed: The Interview album song MP3 by Eminem and download Eminem X-Posed: The Interview song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru 19 rows · Eminem Interview Title: date: source: Eminem, Back Issues (Cover Story) Interview: . 09/05/ · Lil Wayne has officially launched his own radio show on Apple’s Beats 1 channel. On Friday’s (May 8) episode of Young Money Radio, Tunechi and Eminem Author: VIBE Staff. 07/12/ · EMINEM: It was about having the right to stand up to oppression. I mean, that’s exactly what the people in the military and the people who have given their lives for this country have fought for—for everybody to have a voice and to protest injustices and speak out against shit that’s wrong. Eminem interview with BBC Radio 1 () Eminem interview with MTV () NY Rock interview with Eminem - "It's lonely at the top" () Spin Magazine interview with Eminem - "Chocolate on the inside" () Brian McCollum interview with Eminem - "Fame leaves sour aftertaste" () Eminem Interview with Music - "Oh Yes, It's Shady's Night. Eminem will host a three-hour-long special, “Music To Be Quarantined By”, Apr 28th Eminem StockX Collab To Benefit COVID Solidarity Response Fund. -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005. -

Floetry to Feat Rap Artist Common on Supastar

Floetry To Feat Rap Artist Common on SupaStar Written by Robert ID1831 Tuesday, 23 August 2005 06:50 - It's more than their beauty. It’s more than the passionate vocals of Marsha Ambrosius (the Songstress) and elegant spoken word of Natalie Stewart (the Floacist) that has fans captivated everywhere since FLOETRY first stepped on stage. The dynamic duo's incredible success is deeply rooted in their ability to appeal to all ages, races and genres of music lovers. The proof is in their long list of accolades and demand for appearances: six Grammy nods, six Soul Train awards perched on their mantle, a NAACP nomination for Outstanding New Artist, a standing ovation at BET's Walk of Fame: Tribute to Smokey Robinson, impressionable performances at the Essence Music Festival & Def Poetry Jam (HBO). FLOETRY known to make music that speaks to listeners'' mind, body, and soul are now ready to release a masterpiece to stand the test of time and raise the bar in music with their third CD Flo''Ology on Geffen Records. Plus, they''ve enlisted super producer Scott Storch and Hip-Hop's savior rap artist Common on their 1st single, "SupaStar". Fresh off the Kool Philosophy Tour with The Roots and the Sugar Water Festival Tour alongside Queen Latifah, Erykah Badu and Jill Scott, FLOETRY are quick to point out the differences between Flo''Ology and the topics covered on their 6X Grammy-nominated debut Floetic and its follow-up, Floacism (Live). This time, the duo's lyrics more specifically span the spectrum of romantic relationships. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with James Poyser

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with James Poyser Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Poyser, James, 1967- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with James Poyser, Dates: May 6, 2014 Bulk Dates: 2014 Physical 7 uncompressed MOV digital video files (3:06:29). Description: Abstract: Songwriter, producer, and musician James Poyser (1967 - ) was co-founder of the Axis Music Group and founding member of the musical collective Soulquarians. He was a Grammy award- winning songwriter, musician and multi-platinum producer. Poyser was also a regular member of The Roots, and joined them as the houseband for NBC's The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. Poyser was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on May 6, 2014, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2014_143 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Songwriter, producer and musician James Jason Poyser was born in Sheffield, England in 1967 to Jamaican parents Reverend Felix and Lilith Poyser. Poyser’s family moved to West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania when he was nine years old and he discovered his musical talents in the church. Poyser attended Philadelphia Public Schools and graduated from Temple University with his B.S. degree in finance. Upon graduation, Poyser apprenticed with the songwriting/producing duo Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. Poyser then established the Axis Music Group with his partners, Vikter Duplaix and Chauncey Childs. He became a founding member of the musical collective Soulquarians and went on to write and produce songs for various legendary and award-winning artists including Erykah Badu, Mariah Carey, John Legend, Lauryn Hill, Common, Anthony Hamilton, D'Angelo, The Roots, and Keyshia Cole. -

Perspectives of Saskatchewan Dakota/Lakota Elders on the Treaty Process Within Canada.” Please Read This Form Carefully, and Feel Free to Ask Questions You Might Have

Perspectives of Saskatchewan Dakota/Lakota Elders on the Treaty Process within Canada A Dissertation Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Interdisciplinary Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Leo J. Omani © Leo J. Omani, copyright March, 2010. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of the thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis was completed. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain is not to be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Request for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis, in whole or part should be addressed to: Graduate Chair, Interdisciplinary Committee Interdisciplinary Studies Program College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan Room C180 Administration Building 105 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada S7N 5A2 i ABSTRACT This ethnographic dissertation study contains a total of six chapters. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Metric Ambiguity and Flow in Rap Music: a Corpus-Assisted Study of Outkast’S “Mainstream” (1996)

Metric Ambiguity and Flow in Rap Music: A Corpus-Assisted Study of Outkast’s “Mainstream” (1996) MITCHELL OHRINER[1] University of Denver ABSTRACT: Recent years have seen the rise of musical corpus studies, primarily detailing harmonic tendencies of tonal music. This article extends this scholarship by addressing a new genre (rap music) and a new parameter of focus (rhythm). More specifically, I use corpus methods to investigate the relation between metric ambivalence in the instrumental parts of a rap track (i.e., the beat) and an emcee’s rap delivery (i.e., the flow). Unlike virtually every other rap track, the instrumental tracks of Outkast’s “Mainstream” (1996) simultaneously afford hearing both a four-beat and a three-beat metric cycle. Because three-beat durations between rhymes, phrase endings, and reiterated rhythmic patterns are rare in rap music, an abundance of them within a verse of “Mainstream” suggests that an emcee highlights the three-beat cycle, especially if that emcee is not prone to such durations more generally. Through the construction of three corpora, one representative of the genre as a whole, and two that are artist specific, I show how the emcee T-Mo Goodie’s expressive practice highlights the rare three-beat affordances of the track. Submitted 2015 July 15; accepted 2015 December 15. KEYWORDS: corpus studies, rap music, flow, T-Mo Goodie, Outkast THIS article uses methods of corpus studies to address questions of creative practice in rap music, specifically how the material of the rapping voice—what emcees, hip-hop heads, and scholars call “the flow”—relates to the material of the previously recorded instrumental tracks collectively known as the beat.