Beethoven's "Eroica" | the Philadelphia Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Release: Tk, 2013

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 20, 2014 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] The Mary and James G. Wallach Artist-in-Residence YEFIM BRONFMAN To Be Featured in CHAMBER MUSIC CONCERT with New York Philharmonic Musicians A Co-Presentation with 92nd Street Y Schubert’s Sonatina in A minor Bartók’s Contrasts for Violin, Clarinet, and Piano Brahms’s Piano Quintet March 30, 2014, at 92nd Street Y Yefim Bronfman, the New York Philharmonic’s 2013–14 Mary and James G. Wallach Artist-in- Residence, will be spotlighted in a chamber music concert co-presented with 92nd Street Y. Mr. Bronfman will be joined by Philharmonic Concertmaster Glenn Dicterow; Principal Clarinet Stephen Williamson; Associate Principal, Second Violin Group, Lisa Kim; Associate Principal Viola Rebecca Young; and cellist Maria Kitsopoulos for the program, featuring Schubert’s Sonatina in A minor; Bartók’s Contrasts for Violin, Clarinet, and Piano; and Brahms’s Piano Quintet, Sunday, March 30, 2014, at 3:00 p.m. at 92nd Street Y. During his residency, Mr. Bronfman has performed on CONTACT!, the Philharmonic’s new- music series, on a program also co-presented with 92nd Street Y and featuring Philharmonic musicians; Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 on the 2013–14 season subscription-opening program, led by Music Director Alan Gilbert; and a reprise of his Grammy-nominated performance of Magnus Lindberg’s Piano Concerto No. 2 with Alan Gilbert and the Orchestra in New York and on the ASIA / WINTER 2014 tour. He will return as the featured soloist in The Beethoven Piano Concertos: A Philharmonic Festival, led by Alan Gilbert, June 11–28, 2014. -

October 2015

October 2015 Bertrand Chamayou INSIDE: Ian Bostridge | Sarah Connolly Ehnes Quartet | Thomas Hampson Alina Ibragimova & Cédric Tiberghien Magdalena Kozˇená & Mitsuko Uchida Steven Isserlis | Robert Levin Sandrine Piau | Christoph Prégardien Stile Antico | Vox Luminis And many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. Please note that the Box Office with be closed for bookings in person from Monday 27 July to Friday 4 September. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–Y Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – Y AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats. -

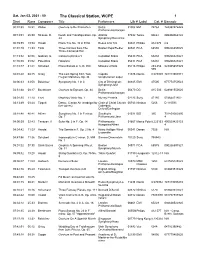

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:31 Weber Overture to Der Freischutz Berlin 01006 EMI 74764 724357476423 Philharmonic/Karajan 00:13:0125:39 Strauss, R. Death and Transfiguration, Op. Atlanta 07032 Telarc 80661 089408066122 24 Symphony/Runnicles 00:39:55 19:54 Haydn Piano Trio No. 36 in E flat Beaux Arts Trio 04027 Philips 432 070 n/a 01:01:1911:33 Falla Three Dances from The Boston Pops/Fiedler 04581 RCA 68550 090266855025 Three-Cornered Hat 01:13:5202:08 Gabrieli, G. Canzona prima a 5 Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:16:00 01:02 Palestrina Hosanna Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:18:1741:41 Schubert Piano Sonata in A, D. 959 Mitsuko Uchida 05116 Philips 289 456 028945657929 579 02:01:2804:15 Grieg The Last Spring from Two Capella 11036 Naxos 8.578009 747313800971 Elegiac Melodies, Op. 34 Istropolitana/Leaper 02:06:4343:50 Balakirev Symphony No. 1 in C City of Birmingham 00845 EMI 47505 077774750523 Symphony/Jarvi 02:51:4808:17 Beethoven Overture to Egmont, Op. 84 Berlin 00470 DG 415 506 028941550620 Philharmonic/Karajan 03:01:3511:14 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Murray Perahia 02233 Sony 47180 07464471802 03:13:4903:44 Tippett Dance, Clarion Air (madrigal for Choir of Christ Church 00783 Nimbus 5266 D 110593 five voices) Cathedral, Oxford/Darlington 03:18:4840:41 Alfven Symphony No. 1 In F minor, Stockholm 01531 BIS 395 731859000395 Op. 7 Philharmonic/Jarvi 4 04:00:5932:43 Taneyev, A. -

Preview Notes • Week Four • Persons Auditorium

2019 Preview Notes • Week Four • Persons Auditorium Saturday, August 3 at 8:00pm Sieben frühe Lieder (1905-08) Dolce Cantavi (2015) Alban Berg Caroline Shaw Born February 9, 1885 Born August 1, 1982 Died December 24, 1935 Duration: approx. 3 minutes Duration: approx. 15 minutes Marlboro premiere Last Marlboro performance: 1997 Berg’s Sieben frühe Liede, literally “seven early songs,” As she has done in other works such as her piano were written while he was still a student of Arnold concerto for Jonathan Biss, which was inspired by Schoenberg. In fact, three of these songs were premiered Beethoven’s third piano concerto, Shaw looks into music in a concert by Schoenberg’s students in late 1907, history to compose music for the present. This piece in around the time that Berg met the woman whom he particular eschews fixed meter to recall the conventions would marry. In honor of the 10-year anniversary of this of early music and to highlight the natural rhythms of the meeting, he later revisited and corrected a final version of libretto. The text of this short but wonderfully involved the songs. The whole set was not published until 1928, song is taken from a poem by Francesca Turini Bufalini when Berg arranged an orchestrated version. Each song (1553-1641). Not only does the language harken back to features text by a different poet, so there is no through- an artistic period before our own, but the music flits narrative, however the songs all feature similar themes, through references of erstwhile luminaries such as revolving around night, longing, and infatuation. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jan 26, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:39 Mozart Adagio in B minor, K. 540 Mitsuko Uchida 00264 Philips 412 616 028941261625 00:13:3945:17 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. du Pre/Swedish Radio 07040 Teldec 85340 685738534029 104 Symphony/Celibidache 01:00:2631:11 Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 in C, Op. Tokyo String Quartet 04508 Harmonia 807424 093046742362 59 No. 3 Mundi 01:32:3708:09 Mozart Adagio & Fugue in C minor for Berlin 06660 DG 0005830 028947759546 Strings K. 546 Philharmonic/Karajan 01:42:1618:09 Telemann Paris Quartet No. 11 Kuijken 04867 Sony 63115 074646311523 Bros/Leonhardt 02:01:5529:22 Mozart Sinfonia Concertante in E flat, Frang/Rysanov/Arcang 12341 Warner 08256462 825646276776 K. 364 elo/Cohen Classics 76776 02:32:1726:39 Brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. Stoltzman/Ax/Ma 02937 Sony 57499 074645749921 114 Classical 03:00:2611:52 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Evgeny Kissin 06623 RCA 58420 828765842020 03:13:1834:42 Strauss, R. Symphony in D minor Hong Kong 03667 Marco Polo 8.220323 73009923232 Philharmonic/Scherme rhorn 03:49:0009:52 Schubert Overture to Rosamunde, D. Leipzig Gewandhaus 00217 Philips 412 432 028941243225 797 Orchestra/Masur 04:00:2215:04 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 50 in D Julia Cload 02053 Meridian 84083 N/A 04:16:2628:32 Mozart Symphony No. 29 in A, K. 201 Prague Chamber 05596 Telarc 80300 089408030024 Orch/Mackerras 04:45:58 12:20 Webern In the Summer Wind Philadelphia 10424 Sony 88725417 887254172024 Orchestra/Ormandy 202 04:59:4806:23 Lehar Merry Widow Waltz Richard Hayman 08261 Naxos 8.578041- 747313804177 Symphony 42 05:07:11 21:52 Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Entremont/Philadelphia 04207 Sony 46541 07464465412 Paganini, Op. -

Learning to Play Like the Great Pianists

Learning to Play Like the Great Pianists Asmir Tobudic Gerhard Widmer Austrian Research Institute for Department of Computational Perception, Artificial Intelligence, Vienna Johannes Kepler University, Linz [email protected] Austrian Research Institute for Artificial Intelligence, Vienna [email protected] Abstract CD recordings and the printed score of the music. Exper- iments show that the system indeed captures some aspect of An application of relational instance-based learn- the pianists' playing style: the machine's performances of un- ing to the complex task of expressive music per- seen pieces are substantially closer to the real performances formance is presented. We investigate to what ex- of the `training' pianist than those of all other pianists in our tent a machine can automatically build `expres- data set. An interesting by-product of the pianists' `expres- sive profiles’ of famous pianists using only min- sive models' is demonstrated: the automatic identification of imal performance information extracted from au- pianists based on their style of playing. And finally, the ques- dio CD recordings by pianists and the printed tion of automatic style replication is briefly discussed. score of the played music. It turns out that the The rest of the paper is laid out as follows. After a short machine-generated expressive performances on un- introduction to the notion of expressive music performance seen pieces are substantially closer to the real per- (Section 2), Section 3 describes the data and its representa- formances of the `trainer' pianist than those of all tion in FOL. We also discuss how the complex task of learn- others. -

Proposed Cultural Awareness Schedule for 2000

CULTURAL ARTS SERIES 2008– 2009 (Schedule) A Classical Celebration! Oklahoma City Community College Artist Performance Date Lark Chamber Artists – Strings, Piano, Woodwinds, and Percussion Tues. Sept. 16, 7:00 P.M. The Romeros – Guitar Quartet (Special venue; Westminster Presbyterian Church) Tues. Oct. 7, 7:00 P.M. Jerusalem Lyric Trio – Soprano, Flute, and Piano Tues. Nov. 18, 7:00 P.M. The Four Freshmen – Vocal Quartet Tues. Dec. 2, 7:00 P.M. The Texas Gypsies – Gypsy/Texas Swing Jazz Quintet Tues. Feb. 17, 7:00 P.M. Rosario Andino – Pianist Tues. Mar. 3, 7:00 P.M. Best of Broadway – Vocal Trio Tues. Apr. 14, 7:00 P.M. Brad Richter, Viktor Uzur – Guitar and Cello Thurs. May 7, 7:00 p.m. • Lark Chamber Artists – Strings, Piano, Woodwinds, and Percussion Ensemble Lecture – TBA Performance – Tuesday, September 16, 2008, 7:00 p.m., Oklahoma City Community College Theatre. A diverse selection of musical delights. (Short) Lark Chamber Artists present a broad range of musical styles, embracing the traditional as well as adventuresome commissions and collaborations. (Medium) Lark Chamber Artists is a uniquely structured ensemble who present a broad range of musical styles, embracing the traditional favorites of the chamber music repertoire, as well as adventuresome commissions and collaborations for a new standard in innovative programming. (Long) As an outgrowth of the world-renowned Lark Quartet, Lark Chamber Artists (LCA) is a uniquely structured ensemble featuring some of today's most active performers who have come together to present a broad range of musical styles, embracing the traditional favorites of the chamber music repertoire, as well as adventuresome commissions and collaborations for a new standard in innovative programming. -

2017-2018 Master Class-Leon Fleisher

Welcome to the 2017-2018 season. The talented students and extraordinary faculty of the Lynn LEON FLEISHER MASTER CLASS Conservatory of Music take this opportunity to share with you the beautiful world of music. Your Wednesday, January 24, 2018 at 7:00 pm ongoing support ensures our place among the premier conservatories Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall of the world and a staple of our community. - Jon Robertson, dean PROGRAM There are a number of ways by which you can help us fulfill our mission: Friends of the Conservatory of Music Sonata Op. 2 No. 2 in A Major Ludwig van Beethoven Lynn University’s Friends of the Conservatory of Music is a IV Rondo: Grazioso (1770-1827) volunteer organization that supports high-quality music education through fundraising and community outreach. Raising more than $2 million since 2003, the Friends support Lynn’s effort to provide Chance Israel, piano free tuition scholarships and room and board to all Conservatory of Music students. The group also raises money for the Dean’s Discretionary Fund, which supports the immediate needs of the university’s music performance students. This is accomplished through annual gifts and special events, such as outreach concerts and the annual Gingerbread Holiday Concert. To learn more about joining the Friends and its many benefits, Scherzo No. 4 in E Major Frederic Chopin such as complimentary concert admission, visit Give.lynn.edu/support-music. (1810-1849) The Leadership Society of Lynn University Meiyu Wu, piano The Leadership Society is the premier annual giving society for donors who are committed to ensuring a standard of excellence at Lynn for all students. -

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonatas Vol

JONATHAN BISS BEETHOVEN Piano Sonatas Vol. 3 Nos 15,16 & 21 PIANO SONATAS, Vol 3 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Piano Sonata No.15 in D major, Op.28 1 Allegro 9.15 2 Andante 6.19 3 Scherzo: Allegro vivace 2.20 4 Rondo: Allegro ma non troppo 4.58 Piano Sonata No.16 in G major, Op.31 No.1 5 Allegro vivace 6.22 6 Adagio grazioso 10.09 7 Rondo, allegretto – Presto 6.29 Piano Sonata No.21 in C major, Op.53 (‘Waldstein’) 8 Allegro con brio 10.40 9 Introduzione: Adagio molto – Attacca (in F major) 3.50 10 Rondo. Allegretto moderato – Prestissimo 10.00 Total time 70.26 Jonathan Biss, piano 2 Sonatas 15, 16, 21 (‘Waldstein’) Beethoven wrote his 32 piano sonatas over the course of 27 years; only four of those years, from the turbulent centre of Beethoven’s altogether turbulent life, are represented on this album. And yet, despite that narrow span of time, the range of expression in these sonatas is anything but narrow. (That this would be the case with more-or-less any three of the 32 sonatas explains why the project of recording the lot of them is so irresistible.) It is, in fact, infinite, moving in turn from subtle to sly, to, finally, cosmic. The first two sonatas heard here were written primarily in 1801, a year that brought dramatic shifts in Beethoven’s conception of the sonata. It was in that year that Beethoven announced to Czerny that he would be taking a “new path”. -

San Diego Chamber Orchestra Concert to Include Music by Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms

San Diego Chamber Orchestra concert to include music by Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms March 30, 1973 A free program of music by Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms will be presented by the San Diego Chamber Orchestra at the University of California, San Diego at 4:30 p.m., Sunday, April 8. The concert, conducted by Glenn Block, will be held in the Recital Hall, Bldg. 409 on the Matthews Campus. The program will include Mozart's "Overture to the Opera, 'Don Giovanni,"' and Brahms' "Serenade No. 1 in D Major, Op. ll." Beethoven's "Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 37" will feature Mary Alderdice as pianist. A California born composer, Ms. Alderdice attended the Interlochen Arts Academy and the Eastman School of Music. She studied the work of Bach with Rosalyn Tureck and has also been a student of Leon Fleisher. She has been awarded an International Bach Society Fellowship and performed recently at the Marlboro Music Festival. The San Diego Chamber Orchestra is an ensemble dedicated to creating a new system of orchestral performance which acts as an alternative to the more traditional system of performance of most professional and amateur orchestras. To achieve this new system of performance requires the ensemble to be totally free of any divisive elements that would destroy the interpersonal structure and relationships among members and the various sections of the orchestra. Members feel that traditional orchestra has developed such a highly competitive system that these relationships are destroyed. Members of the Chamber Orchestra also perform as principal players and members of the Civic Youth Orchestra, the San Diego Symphony, and the California State University Orchestra. -

2O21-22 Season

CELEBRATING 2O21-22 SEASON EST. 1996 2021-22 contents 5 Welcome 6 Season Calendar 8 Subscribe 10 Series 22 Performances 86 Performances for Young People 88 How to Order 89 Discounts 91 Helpful Information 92 Beyond the Footlights 94 Support On the cover: Hodgson Concert Hall 2Camerata RCO Painting: J.N. Smith 3 Welcome Back What a time it has been! Our world has experienced unprecedented disruption since we last gathered in the spring of 2020 in our beautiful venues to witness exquisite music, dance, and theatre together. Throughout these many long and painful months of separation and isolation, I have been yearning for the time when we can be together once again. It appears that time is finally now upon us! I am absolutely thrilled to share our plans for celebrating the University of Georgia Performing Arts Center’s historic 25th anniversary season throughout the fall of 2021 and spring of 2022. Our silver anniversary season will feature a variety of acclaimed guest artists—some new to us and some returning favorites—with an equally wide variety of personal life experiences. They will come to us from across the United States and several different countries. Their experiences inform their work, and we will, for a brief moment in time, commune together as the universal languages of music, spoken word, and movement unite us in hope and healing. Not only has the world changed significantly since we first opened our doors 25 years ago, it has changed dramatically in the last year as we have endured the devastating impact of a global pandemic, social injustice, political uncertainty, and any number of other things. -

The Time Is Now Thethe Timetime Isis Nownow Music Has the Power to Inspire, to Change Lives, to Illuminate Perspective, 20/21 SEASON and to Shift Our Vantage Point

20/21 SEASON The Time Is Now TheThe TimeTime IsIs NowNow Music has the power to inspire, to change lives, to illuminate perspective, 20/21 SEASON and to shift our vantage point. featuring FESTIVAL Your seats are waiting. Voices of Hope: Artists in Times of Oppression An exploration of humankind’s capacity for hope, courage, and resistance in the face of the unimaginable PERSPECTIVES Rhiannon Giddens “… an electrifying artist …” —Smithsonian PERSPECTIVES Yannick Nézet-Séguin “… the greatest generator of energy on the international podium …” —Financial Times PERSPECTIVES Jordi Savall “… a performer of genius but also a conductor, a scholar, a teacher, a concert impresario …” —The New Yorker DEBS COMPOSER’S CHAIR Andrew Norman “… the leading American composer of his generation ...” —Los Angeles Times Left: Youssou NDOUR On the cover: Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla carnegiehall.org/subscribe | 212-247-7800 Photos: NDOUR by Jack Vartoogian, Gražinytė-Tyla by Benjamin Ealovega. Box Office at 57th and Seventh Rafael Pulido Some of the most truly inspiring music CONTENTS you’ll hear this season—or any other season—at Carnegie Hall was written in response to oppressive forces that have 3 ORCHESTRAS ORCHESTRAS darkened the human experience throughout history. Perspectives: Voices of Hope: Artists in Times of Oppression takes audiences Yannick Nézet-Séguin on a journey unique among our festivals for the breadth of music 12 these courageous artists employed—from symphonies to jazz to Debs Composer’s popular songs and more. This music raises the question of why, 13 Chair: Andrew Norman no matter how horrific the circumstances, artists are nonetheless compelled to create art; and how, despite those circumstances, 28 Zankel Hall Center Stage the art they create can be so elevating.