The Fatherland of Apples the Origins of a Favorite Fruit and the Race to Save Its Native Habitat by Gary Paul Nabhan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

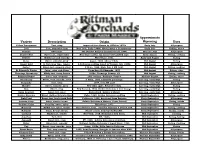

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

Bramble Volume 21, Issue 3

VOLUME 21, ISSUE 3 THE BRAMBLE AUTUMN, 2005 THE NEWSLETTER OF THE NORTH AMERICAN BRAMBLE GROWERS ASSOCIATION, INC. Request for Proposals ***** NABGA Annual Meeting & Conference ***** The North American Bramble Growers January 5-6, 2006 – Savannah, Georgia Research Foundation (NABGRF) is Our 2006 Annual Meeting will be held in association with the Georgia Fruit and seeking proposals for bramble research Vegetable Growers Association’s Southeast Fruit and Vegetable Conference (SFVC) in for the year 2006. Since 1999, NABGRF Savannah, Georgia. We hope to see you there! Watch your mailbox and e-mail for has funded a total of 26 proposals, registration details and accommodations information. totaling $50,146. To register for NABGA’s meeting, you will simply register for the SFVC. This All bramble proposals will be conference has a very large trade show and extensive sessions on blueberries, peaches, considered, however preference will be and vegetable crops January 6-8. Fees are very reasonable and both one-day and three- given to proposals related to: day registrations are available. The North American Strawberry Growers Association • cultivar development and testing (NASGA) will be meeting here (as the “North American Berry Conference”), on • pest management strategies January 4-6, with educational sessions on the 4th, a tour on January 5, and general • cultural management strategies to im- sessions the morning of the 6th. A forum on the National Berry Crops Initiative prove yield, quality and profitability Strategic Plan for the Berry Industry (see pages 8-9) is planned for Saturday, January • identification of beneficial com- 7. This concentration and combination of oppportunities is well worth the trip. -

Survey of Apple Clones in the United States

Historic, archived document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. 5 ARS 34-37-1 May 1963 A Survey of Apple Clones in the United States u. S. DFPT. OF AGRffini r U>2 4 L964 Agricultural Research Service U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE PREFACE This publication reports on surveys of the deciduous fruit and nut clones being maintained at the Federal and State experiment stations in the United States. It will b- published in three c parts: I. Apples, II. Stone Fruit. , UI, Pears, Nuts, and Other Fruits. This survey was conducted at the request of the National Coor- dinating Committee on New Crops. Its purpose is to obtain an indication of the volume of material that would be involved in establishing clonal germ plasm repositories for the use of fruit breeders throughout the country. ACKNOWLEDGMENT Gratitude is expressed for the assistance of H. F. Winters of the New Crops Research Branch, Crops Research Division, Agricultural Research Service, under whose direction the questionnaire was designed and initial distribution made. The author also acknowledges the work of D. D. Dolan, W. R. Langford, W. H. Skrdla, and L. A. Mullen, coordinators of the New Crops Regional Cooperative Program, through whom the data used in this survey were obtained from the State experiment stations. Finally, it is recognized that much extracurricular work was expended by the various experiment stations in completing the questionnaires. : CONTENTS Introduction 1 Germany 298 Key to reporting stations. „ . 4 Soviet Union . 302 Abbreviations used in descriptions .... 6 Sweden . 303 Sports United States selections 304 Baldwin. -

An Old Rose: the Apple

This is a republication of an article which first appeared in the March/April 2002 issue of Garden Compass Magazine New apple varieties never quite Rosaceae, the rose family, is vast, complex and downright confusing at times. completely overshadow the old ones because, as with roses, a variety is new only until the next This complexity has no better exemplar than the prince of the rose family, Malus, better known as the variety comes along and takes its apple. The apple is older in cultivation than the rose. It presents all the extremes in color, size, fragrance place. and plant character of its rose cousin plus an important added benefit—flavor! One can find apples to suit nearly every taste and cultural demand. Without any special care, apples grow where no roses dare. Hardy varieties like the Pippins, Pearmains, Snow, Lady and Northern Spy have been grown successfully in many different climates across the U.S. With 8,000-plus varieties worldwide and with new ones introduced annually, apple collectors in most climates are like kids in a candy store. New, Favorite and Powerhouse Apples New introductions such as Honeycrisp, Cameo and Pink Lady are adapted to a wide range of climates and are beginning to be planted in large quantities. The rich flavors of old favorites like Spitzenburg and Golden Russet Each one is a unique eating experience that are always a pleasant surprise for satisfies a modern taste—crunchy firmness, plenty inexperienced tasters. of sweetness and tantalizing flavor. Old and antique apples distinguish These new varieties show promise in the themselves with unusual skin competition for the #1 spot in the world’s colors and lingering aftertastes produce sections and farmers’ markets. -

Cold Damage Cultivar Akero 0 Albion 0 Alexander 0 Alkmene 0 Almata 0

Cold Damage Table 16 1. less than 5% Bud 118 0 2. 5-15% Bud 9 on Ranetka 0 3. More than 15%. Cultivar 4. severe (50% ) Carroll 0 Akero 0 Centennial 0 Albion 0 Chehalis 0 Alexander 0 Chestnut Crab 0 Alkmene 0 Collet 0 Almata 0 Collins 0 American Beauty 0 Crab 24 false yarlington 0 Anaros 0 Cranberry 0 Anoka 0 Croncels 0 Antonovka 81 0 Dan Silver 0 Antonovka 102 0 Davey 0 Antonovka 109 0 Dawn 0 antonovka 52 0 Deane 0 Antonovka 114 0 Dolgo (grafted) 0 Antonovka 1.5 0 Douce Charleviox 0 Antonovka 172670-B 0 Duchess 0 Antonovka 37 0 Dudley 0 Antonovka 48 0 Dudley Winter 0 Antonovka 49 0 Dunning 0 Antonovka 54 0 Early Harvest 0 Antonovka Debnicka 0 Elstar 0 Antonovka Kamenichka 0 Equinox 0 Antonovka Monasir 0 Erwin Bauer 0 Antonovka Shafrain 0 Fameuse 0 Aroma 0 Fantazja 0 Ashmead's Kernal 0 Fox Hill 0 Audrey 0 Frostbite TM 0 Autumn Arctic 0 Garland 0 Baccata 0 Geneva 0 Banane Amere 0 Gideon 0 Beacon 0 Gilpin 0 Beautiful Arcade 0 Gingergold 0 Bedford 0 Golden Russet 0 Bessemianka Michurina 0 Granny Smith Seedling 0 Bilodeau 0 Green Peak 0 Black Oxford 0 Greenkpeak 0 Blue Pearmain 0 Greensleeves 0 Borovitsky 0 Haralred 0 Breaky 0 Haralson 0 Cold Damage Table 16 1. less than 5% McIntosh 0 2. 5-15% Melba 0 3. More than 15%. Cultivar 4. severe (50% ) Miami 0 Harcourt 0 Minnehaha 0 Hawaii 0 MN 85-22-99 0 Herring's Pippin 0 MN 85-23-21 0 Hewe's Crab 0 MN 85-27-43 0 Hiburnal 0 Morden 0 Honeygold 0 Morden 359 0 Hyslop Crab 0 Niedzwetzkyana 0 Island Winter 0 No Blow 0 Jersey Mac 0 Noran 0 Jonamac 0 Noret 0 Jonathan 0 Norhey 0 Kazakh 1 0 Norland 0 Kazakh -

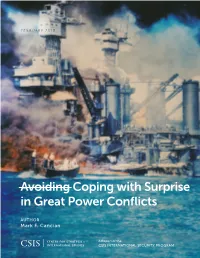

Avoiding Coping with Surprise in Great Power Conflicts

COVER PHOTO UNITED STATES NAVAL INSTITUTE FEBRUARY 2018 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 202 887 0200 | www.csis.org Avoiding Coping with Surprise in Great Power Conflicts AUTHOR Mark F. Cancian A Report of the CSIS INTERNATIONAL SECURITY PROGRAM Blank FEBRUARY 2018 Avoiding Coping with Surprise in Great Power Conflicts AUTHOR Mark F. Cancian A Report of the CSIS INTERNATIONAL SECURITY PROGRAM About CSIS For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked to develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. Today, CSIS scholars are providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 fulltime staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. Thomas J. Pritzker was named chairman of the CSIS Board of Trustees in November 2015. Former U.S. deputy secretary of defense John J. Hamre has served as the Center’s president and chief executive officer since 2000. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. -

Potrzeby I Aktualne Możliwości Ochrony Jabłoni Przed Chorobami W

Hanna BRYK, Witold DANELSKI, Teresa BADOWSKA-CZUBIK Research Institute of Horticulture, Division of Pomology ul. Pomologiczna 18, 96-100 Skierniewice, Poland e-mail: [email protected] INJURIES TO ‘TOPAZ’ AND ‘PINOVA’ APPLES BY PESTS IN AN ORGANIC ORCHARD AND THEIR EFFECT ON FRUIT STORABILITY Summary During two storage seasons, in the years 2011/2012 and 2012/2013, a study was conducted in the Experimental Ecological Orchard of the Research Institute of Horticulture in Skierniewice on the extent of pest damage to apples of the cultivars ‘Topaz’ and ‘Pinova’ and on the storability of the damaged fruit. The trees of both cultivars were protected with the pesti- cides permitted in organic production. It was found that, regardless of the cultivar, the injuries to apples were mostly caused by leafrollers and the rosy apple aphid. On the damaged apples, stored for 5 months in a normal cold store, two dis- eases had occurred – bull`s eye rot (Pezicula spp.) and brown rot (Monilinia fructigena), but very few skin injuries were the spot of disease development. Only on 6.7% of the ‘Topaz’ apples and on 3.7% of the ‘Pinova’ apples did the diseases devel- op in the point of a skin injury. The typical wound disease – the blue mould of apples (Penicillium expansum) was not found on the damaged apples. Key words: organic orchard, apples, cultivars, pest damage, leafrollers, rosy apple aphid, experimentation USZKODZENIA JABŁEK `TOPAZ` I `PINOVA` PRZEZ SZKODNIKI W SADZIE EKOLOGICZNYM I ICH WPŁYW NA PRZECHOWYWANIE OWOCÓW Streszczenie W ciągu dwóch sezonów przechowalniczych 2011/2012 i 2012/2013 prowadzono w Ekologicznym Sadzie Doświadczalnym Instytutu Ogrodnictwa w Skierniewicach badania nad stopniem uszkodzenia jabłek odmian `Topaz` i `Pinova` przez szkod- niki oraz zdolnością przechowalniczą uszkodzonych owoców. -

Fruits, Old and New and Northern Plant Novelties N

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange South Dakota State University Agricultural Bulletins Experiment Station 3-1-1937 Fruits, Old and New and Northern Plant Novelties N. E. Hansen Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_bulletins Recommended Citation Hansen, N. E., "Fruits, Old and New and Northern Plant Novelties" (1937). Bulletins. Paper 309. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_bulletins/309 This Bulletin is brought to you for free and open access by the South Dakota State University Agricultural Experiment Station at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bulletin No. 309 ·March; 1937 Fruits, Old and New and Northern Plant Novelties By N. E. Hansen Department of Horticulture Agricultural Experiment Station South Dakota State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts Brookings, S. D. 2 BULLETIN 309 SOUTH DAKOTA EXPERIMENT STATION 1937 Hardy Fruit List for South Dakota By N. E. Hansen, Horticultur,ist This list of fruits recommended for. planting will vary because of local conditions. Planters in the extreme southern and southeastern edge of the state will be interested in the fruit lists of northern Nebraska and northern Iowa. For the eastern and northeastern counties, across the state, the North Dakota list should be studied. The Black Hills region is more sheltered and can grow many varieties not hardy on the open prairies further east. -

Apple, Reaktion Books

apple Reaktion’s Botanical series is the first of its kind, integrating horticultural and botanical writing with a broader account of the cultural and social impact of trees, plants and flowers. Already published Apple Marcia Reiss Bamboo Susanne Lucas Cannabis Chris Duvall Geranium Kasia Boddy Grasses Stephen A. Harris Lily Marcia Reiss Oak Peter Young Pine Laura Mason Willow Alison Syme |ew Fred Hageneder APPLE Y Marcia Reiss reaktion books Published by reaktion books ltd 33 Great Sutton Street London ec1v 0dx, uk www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2015 Copyright © Marcia Reiss 2015 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978 1 78023 340 6 Contents Y Introduction: Backyard Apples 7 one Out of the Wild: An Ode and a Lament 15 two A Rose is a Rose is a Rose . is an Apple 19 three The Search for Sweetness 43 four Cider Chronicles 59 five The American Apple 77 six Apple Adulation 101 seven Good Apples 123 eight Bad Apples 137 nine Misplaced Apples 157 ten The Politics of Pomology 169 eleven Apples Today and Tomorrow 185 Apple Varieties 203 Timeline 230 References 234 Select Bibliography 245 Associations and Websites 246 Acknowledgements 248 Photo Acknowledgements 250 Index 252 Introduction: Backyard Apples Y hree old apple trees, the survivors of an unknown orchard, still grow around my mid-nineteenth-century home in ∏ upstate New York. -

Genetic Diversity of Red-Fleshed Apples (Malus)

Euphytica DOI 10.1007/s10681-011-0579-7 Genetic diversity of red-fleshed apples (Malus) Steven van Nocker • Garrett Berry • James Najdowski • Roberto Michelutti • Margie Luffman • Philip Forsline • Nihad Alsmairat • Randy Beaudry • Muraleedharan G. Nair • Matthew Ordidge Received: 31 May 2011 / Accepted: 3 November 2011 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 Abstract Anthocyanins are flavonoid pigments including the core and cortex (flesh). Red-fleshed imparting red, blue, or purple pigmentation to fruits, apple genotypes are an attractive starting point for flowers and foliage. These compounds are powerful development of novel varieties for consumption and antioxidants in vitro, and are widely believed to nutraceutical use through traditional breeding and contribute to human health. The fruit of the domestic biotechnology. However, cultivar development is apple (Malus x domestica) is a popular and important limited by lack of characterization of the diversity source of nutrients, and is considered one of the top of genetic backgrounds showing this trait. We iden- ‘functional foods’—those foods that have inherent tified and cataloged red-fleshed apple genotypes from health-promoting benefits beyond basic nutritional four Malus diversity collections representing over value. The pigmentation of typical red apple fruits 3,000 accessions including domestic cultivars, wild results from accumulation of anthocyanin in the skin. species, and named hybrids. We found a striking However, numerous genotypes of Malus are known range of flesh color intensity -

Eden Winter 2021

Winter 2021 Journal of the California Garden & Landscape History Society Volume 24, Number 1 JOURNAL OF THE CALIFORNIA GARDEN & LANDSCAPE HISTORY SOCIETY EDEN EDITORIAL BOARD Editor: Steven Keylon Editorial Board: Keith Park (Chair), Kate Nowell, Ann Scheid, Susan Schenk, Libby Simon, Noel Vernon Regional Correspondents: Sacramento: Carol Roland-Nawi, San Diego: Vonn Marie May, San Francisco Bay Area: Janet Gracyk Consulting Editors: Marlea Graham, Barbara Marinacci Graphic Design: designSimple.com Submissions: Send scholarly papers, articles, and book reviews to the editor: [email protected] Memberships/Subscriptions: Join the CGLHS and receive a subscription to Eden. Individual $50 • Family $75 Sustaining $150 and above Student $20 Nonprofit/Library $50 Visit www.cglhs.org to join or renew your membership. Or mail check to California Garden & Landscape History Society, PO Box 220237, Newhall, CA 91322-0237. Questions or Address Changes: [email protected] CGLHS BOARD OF DIRECTORS President: Keith Park Vice Presidents: Eleanor Cox and Kate Nowell Recording Secretary: Nancy Carol Carter Contents Membership Officer: Janet Gracyk Treasurer: Patrick O’Hara Directors at large: Antonia Adezio, Kelly Comras, Judy Horton, Kathleen Albert Etter: Humboldt County's Horticultural Genius Kennedy, Ann Scheid, Libby Simon, Alexis Davis Millar Tom Hart ..................................................................................................................................................4 Past President: Christy O’Hara PUBLISHER’S CIRCLE The California