Apple, Reaktion Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

In-Room Dining

IN-ROOM DINING Phone Number: 518-628-5150 In-Room Dial: 204 BREAKFAST 8:00am - 10:30am | Thursday - Monday To Order: Call during hours of service and your food will be delivered to your door. The server will knock on your door to let you know that your meal has arrived. Limited outdoor dining is available, first come first serve. LUNCH 12:00pm - 3:00pm | Thursday - Monday To Order: Call during hours of service and your food will be delivered to your door. The server will knock on your door to let you know that your meal has arrived. Limited outdoor dining is available, first come first serve. SNACKS 3:00pm - 5:00pm | Thursday - Sunday To Order: Call during hours of service and your food will be delivered to your door. The server will knock on your door to let you know that your meal has arrived. Limited outdoor dining is available, first come first serve. DINNER 6:00pm - 9:00pm | Wednesday - Sunday To Order: Call during hours of service and your food will be delivered to your door. The server will knock on your door to let you know that your meal has arrived. Limited outdoor table reservations are available, check with the front desk. Dining on the Prospect deck is weather dependent. All In-Room Dining orders will be charged to your room + tax + 18% service fee. We kindly ask for all in-room dining orders to meet a minimum of $20. Please alert your server of any dietary restrictions or allergies. Eating raw or undercooked fish, shellfish, eggs or meat increases the risk of foodborne illness. -

APPLE (Fruit Varieties)

E TG/14/9 ORIGINAL: English DATE: 2005-04-06 INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NEW VARIETIES OF PLANTS GENEVA * APPLE (Fruit Varieties) UPOV Code: MALUS_DOM (Malus domestica Borkh.) GUIDELINES FOR THE CONDUCT OF TESTS FOR DISTINCTNESS, UNIFORMITY AND STABILITY Alternative Names:* Botanical name English French German Spanish Malus domestica Apple Pommier Apfel Manzano Borkh. The purpose of these guidelines (“Test Guidelines”) is to elaborate the principles contained in the General Introduction (document TG/1/3), and its associated TGP documents, into detailed practical guidance for the harmonized examination of distinctness, uniformity and stability (DUS) and, in particular, to identify appropriate characteristics for the examination of DUS and production of harmonized variety descriptions. ASSOCIATED DOCUMENTS These Test Guidelines should be read in conjunction with the General Introduction and its associated TGP documents. Other associated UPOV documents: TG/163/3 Apple Rootstocks TG/192/1 Ornamental Apple * These names were correct at the time of the introduction of these Test Guidelines but may be revised or updated. [Readers are advised to consult the UPOV Code, which can be found on the UPOV Website (www.upov.int), for the latest information.] i:\orgupov\shared\tg\applefru\tg 14 9 e.doc TG/14/9 Apple, 2005-04-06 - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. SUBJECT OF THESE TEST GUIDELINES..................................................................................................3 2. MATERIAL REQUIRED ...............................................................................................................................3 -

2019 Newsletter

Front page: Allen’s greeting, something new 2019 NEWSLETTER A Message From Our President & Owner, EVENT CALENDAR Cooler mornings and valley fog below the orchard remind us all that it’s about apple time! Nature has blessed us with August 19th a beautiful crop of apples with exceptionally good fruit size. Opening Day Compared to recent years, some varieties may be picked a little later this year so be sure to give us a call or check our website to September 27th - 29th make sure your favorite apple is available. I enjoy every apple Gays Mills Apple Festival variety we grow, but Evercrisp has me as excited as Honeycrisp. October 5th - 6th Harvested in late October and stored in a refrigerator, Evercrisp Sunrise Samples Weekend is a fantastic eating experience in the winter months. Our family has been growing apples since 1934 and we have never tasted October 12th - 13th another winter apple like Evercrisp! Family Fun Weekend I hope you all enjoyed our newly expanded sales area and October 19th - 20th bathrooms added in 2018. This year we have made additional Harvest Celebration exciting improvements with a new gift area, live apple packing & Helicopter Rides TV, and a working model train for young and old to enjoy. Our famous cider donuts will be back- made fresh every day. Please (weather permitting ) enjoy our free apple and cider samples along with many of the October 21st - December 16th other products we sell. Gift Box Shipping Begins Don’t forget our online store. We feature many of the October 26th - 27th items available here and have made it far easier to order gift pack Trick or Treat Weekend apples this year from home. -

Apple Varieties in Maine Frederick Charles Bradford

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 6-1911 Apple Varieties in Maine Frederick Charles Bradford Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Agriculture Commons Recommended Citation Bradford, Frederick Charles, "Apple Varieties in Maine" (1911). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2384. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2384 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Maine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN AGRICULTURE by FREDERICK CHARLES BRADFORD, B. S . Orono, Maine. June, 1911. 8 2 8 5 INTRODUCTION The following pages represent an effort to trace the causes of the changing procession of varieties of apples grown in Maine. To this end the history of fruit growing in Maine has been carefully studied, largely through the Agricultural Reports from 1850 to 1909 and the columns of the Maine Farmer fran 1838 to 1875. The inquiry has been confined as rigidly as possible to this state, out side sources being referred to only for sake of compari son. Rather incidentally, soil influences, modifications due to climate, etc., have been considered. Naturally* since the inquiry was limited to printed record, nothing new has been discovered in this study. Perhaps a somewhat new point of view has been achieved. And, since early Maine pomological literature has been rather neglected by our leading writers, some few forgot ten facts have been exhumed. -

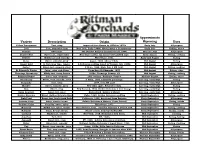

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

The 9Th Annual Great Lakes International Cider & Perry

The 9th Annual Great Lakes International Cider & Perry Competition March 23, 2014 St. Johns, Michigan Results Analysis Eric West Competition Registrar GLINTCAP 2014 Medalists A-Z Noncommercial Division Alan Pearlstein - Michigan Apple Anti-Freeze New England Cider Silver Commerce Township Table Cider Common Cider Silver Andrew Rademacher - Michigan Tin Man Hard Cider Specialty Cider & Perry Bronze Andrew Schaefer - Michigan Rome Crab Common Cider Silver Spy Turley Common Cider Silver Crab Common Cider Bronze Bill Grogan - Wisconsin Northern Dragon Wood Aged Cider & Perry Bronze C. Thomas - Pennsylvania Gilbert + Hale Common Cider Bronze Charlie Nichols - Michigan Black Moon Raspberry Mead Other Fruit Melomel Bronze Char Squared Raspberry Hard Apple Cider Fruit Cider Bronze Staghorn Moon Spiced Hard Apple Cider Specialty Cider & Perry Bronze Charlie Nichols & Joanne Charron - Michigan Staghorn Moon Raspberry Hard Apple Cider Fruit Cider Bronze Chris McGowan - Massachusetts Applewine Applewine Bronze Cherry Cider Specialty Cider & Perry Bronze Rum Barrel Cider New England Cider Bronze Christopher Gottschalk - Michigan Leo Hard Cider Specialty Cider & Perry Bronze Claude Jolicoeur - Quebec Cidre de Glace Intensified (Ice Cider) Silver Colin Post - Minnesota Deer Lake - SM Common Cider Silver Deer Lake - Lalvin Common Cider Bronze Deer Lake - WL/Wy Mix Common Cider Bronze Great Lakes Cider & Perry Association Page 2 www.greatlakescider.com GLINTCAP 2014 Medalists A-Z Noncommercial Division David Catherman & Jeff Biegert - Colorado Red Hawk -

Kale Apple Cake

RECIPE Hero Vegetable: Kale Kale Apple Cake Ingredients: 2 cups fresh kale, stems removed and roughly chopped 2 cups flour 3 apples, cored, and sliced into wedges 1 ¼ cup sugar ½ cup unsalted butter, melted ½ cup milk 3 eggs 1 Tbs lemon juice 2 tsp baking powder 1 tsp vanilla extract ½ tsp salt ¼ cup sliced almonds (optional) powdered sugar for sprinkling(optional) Directions: Preheat your oven to 350F. Grease then fit a round sheet of parchment paper inside the bottom of a 10-inch springform pan, set aside. Steam or lightly boil the kale for about 2 minutes. The kale should be tender. Puree the kale leaves in a blender with a spoonful of water until smooth. Don’t add more water as the kale will release its own juices. (Now if your blender isn’t breaking up the kale easily, you can use the milk at this step instead of later to blend the kale if it makes it easier to puree) In a mixing bowl whisk together the flour, sugar, baking powder, and salt. Beat in the eggs, kale puree, vanilla, lemon juice, and milk, mixing until the batter just combined. Pour in the cooled melted butter and beat until well incorporated. Pour the batter into the prepared baking pan. (If the batter is thick, this is ok. The apples will release juices as the cake bakes.) Arrange the apple slices into the batter, pushing them into the batter slightly. Sprinkle the almonds evenly over the cake batter. Bake the cake for 35-45 minutes, until a toothpick inserted in the center of the cake (not into an apple) comes out clean. -

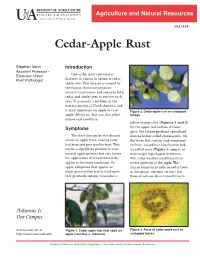

Cedar-Apple Rust

DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE RESEARCH & EXTENSION Agriculture and Natural Resources University of Arkansas System FSA7538 Cedar-Apple Rust Stephen Vann Introduction Assistant Professor One of the most spectacular Extension Urban Plant Pathologist diseases to appear in spring is cedar- apple rust. This disease is caused by the fungus Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae and requires both cedar and apple trees to survive each year. It is mainly a problem in the eastern portion of North America and is most important on apple or crab Figure 2. Cedar-apple rust on crabapple apple (Malus sp), but can also affect foliage. quince and hawthorn. yellow-orange color (Figures 1 and 2). Symptoms On the upper leaf surface of these spots, the fungus produces specialized The chief damage by this disease fruiting bodies called spermagonia. On occurs on apple trees, causing early the lower leaf surface (and sometimes leaf drop and poor quality fruit. This on fruit), raised hair-like fruiting bod can be a significant problem to com ies called aecia (Figure 3) appear as mercial apple growers but also harms microscopic cup-shaped structures. the appearance of ornamental crab Wet, rainy weather conditions favor apples in the home landscape. On severe infection of the apple. The apple, symptoms first appear as fungus forms large galls on cedar trees small green-yellow leaf or fruit spots in the spring (see next section), but that gradually enlarge to become a these structures do not greatly harm Arkansas Is Our Campus Visit our web site at: Figure 1. Cedar-apple rust (leaf spot) on Figure 3. Aecia of cedar-apple rust on https://www.uaex.uada.edu apple (courtesy J. -

STUDENTS to GIVE PLAY. Were Decorated with Green and Gold, %Aee Kwav,, •:;' Albert.L«Hwam, • • Aeven Dead Members

VOLUME XXXVIII. NOa 46 RED BANK, N? J.V WEDNESDAY, MAY 10,1916. •«*•• PAGES 1 TO 10 session-is going to ,be n less interest* ing pnstimo than tending garden and s "putting up" fruit. Each child will 7 get the product of her or his labor, RED BANK FIRM GETS UNUSUAL and the best specimens of vegetables and canned goods will be exhibited at CONTRACT ATJSANDY HOOK. the county agricultural fair. The Building 115 Feet High and Contain- ground for the gardens was plowed ing Ten StoWei Being Moved for a Fridayrnnd-an-eager-knot-of ques- Distance of Half a Mile on Soaped MEW JEHSEY. tioning youngsters followed the Timbers by Thompson & Matthews. ploughman up and down the furrows. 1 One of the biggest moving jobs The members of the two clubs arc ever undertaken, hereabouts is being Those Clubs are under ihe Direction of IVJiss Stolla Mullin, Mildred. Sanborn, Lil- performed at Sandy Hook by Thomp- lian Holmes, Florence Layton, Mary Bpn &' Matthews of jKed Bank f pr the Mouscr, Mary and Frank Kelly, Helen Western Union telegraph company. Florence Brand—Similar Clubs Formed at Lincroft Vaughn,. Maud Norman, Rudella The Red Bank firm is moving an ob- Holmesj Milton and Russell Tomlin- servation tower forfa distance of half —A Garden Club Organized by the Junior Holy son, John Ryon, Tennont Fenton, Jo- a milo. The toweii is 115 feet high seph Mullin, Harold White, Carl Win- and has ten stories, It is moved by flame Society of St. James's Parish. ters, Clarence McQueen and Chester being slid on top af.timbers. -

Cider and Fruit Wine

Dosage Product Description Application (g or mL per 100 kg/L) Dry selected pure yeast for clean Oenoferm® Cider, German Apfelwein 20 – 30 Cider fermentation Oenoferm® Bio Organic pure yeast Cider, mead, red fruit wines 20 – 40 Oenoferm® Yeast Fast-fermenting Bayanus yeast Cider/Perry 20 – 30 Freddo and fruit Oenoferm® Fast-fermenting hybrid yeast Cider, mead, fruit wine 20 – 30 X-treme ® See product VitaDrive F3 Yeast activator Rehydration data sheet Vitamon® Liquid Liquid yeast nutrition Continuous dosage during fermentation Up to 200 wine Vitamon® Plus Nutrition complex Cider fermentation 20 – 100 VitaFerm® Ultra F3 Multi-nutrition complex Difficult to ferment media 30 – 40 Yeast nutrition VitaFerm® Bio Deactivated organic yeast Yeast nutrition for organic fruit wine 30 – 40 Kadifit Potassium metabisulphite, powder Oxidation prevention and microbiological stabilisation 5 – 25 Solution Sulfureuse P15 Liquid SO2, 15% SO2 Oxidation prevention and microbiological stabilisation 5.5 – 55 Blancobent UF Special bentonite, no particles Fining, in-line stabilisation in crossflow filter systems 5 – 200 FloraClair®/LittoFresh® Vegetable fining protein Tannin adsorption, fining 10 – 40 Tannivin® Galléol Fully hydrolysable tannin from oak galls Beverage fining and flavour enhancement 3 – 20 Tannivin® Structure Oenological tannin from quebracho Improved structure and oxidation prevention 3 – 20 Granucol® GE Granulated activated plant charcoal Adsorption of bitter notes 30 – 150 Ercarbon SH Powdered plant charcoal Odour and flavour harmonisation 30 -

Apples Dwarf 6 86080-Fuji $35.99 6 23958-Gravenstein Red-$35.99 6 59580-Honeycrisp-$35.99 7 86082-Jonagold-$35.99 7

Apples Dwarf 6 86080-Fuji $35.99 6 23958-Gravenstein Red-$35.99 6 59580-Honeycrisp-$35.99 7 86082-Jonagold-$35.99 7 Apples Semi-Dwarf 7 13475-Akane-$34.99 7 80926-Amere de Berthcourt $28.99 7 86532-Calypso Redlove $28.99 8 86532-Odysso Redlove $28.99 8 13510-Cox Orange Pippin $34.99 8 13515-Empire-$34.99 9 13530-Fuji $34.99 9 13520-Fuji, Red $34.99 9 98808-Gala-$34.99 9 13555-Golden Delicious -$34.99 10 10010-Granny Smith-$34.99 10 13575-Gravenstein Red-$34.99 10 41238-Jonagold-$34.99 10 10006-Jonathon-$34.99 11 NEW 2020 86148-King David-$34.99 11 13600-King, Thompkins-$34.99 11 13605-Liberty -$34.99 12 27726-Pink Pearl-$34.99 12 98814-Waltana-$34.99 12 98817-Yellow Newton Pippin - $34.99 12 Apples Standard 13 13535-Fuji $31.99 13 Crabapple 13 80864-Dolgo $28.99 13 NEW 2020 86228-Firecracker $28.99 13 Multi Graft & Espalier Apples & Rootstock 14 13465-6N1 Multi-Graft Espalier $69.99 14 61672-Fuji Espalier. $64.99 14 98847- Gala Espalier. $64.99 14 61672-Golden Delicious Espalier. $64.99 14 1 86182-4-N-1 Combos - $64.99 14 17466-Apple Rootstock - $2.59 14 Apricots & Apriums Semi-Dwarf 15 13655-Harglow - $34.99 15 47548-Puget Gold - $32.99 15 83061-Tomcot - $39.99 15 Cherries Sweet Dwarf 15 86154-Bing $41.99 15 86156-Craigs Crimson $41.99 16 35936-Lapins $41.99 16 62618-Stella $42.99 16 Cherries Sweet Semi-Dwarf 16 NEW 2020 86230-Amarena de pescara $28.99 17 86154-Bing $39.99 17 80952-Governor Wood $28.99 17 82362-Lapins $39.99 17 67468-Rainier $39.99 18 NEW 2020 86162-Royal Crimson $42.99 18 80866-Royal Rainier $41.99 18 Cherry’s Sour