Apples: Organic Production Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPLE (Fruit Varieties)

E TG/14/9 ORIGINAL: English DATE: 2005-04-06 INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NEW VARIETIES OF PLANTS GENEVA * APPLE (Fruit Varieties) UPOV Code: MALUS_DOM (Malus domestica Borkh.) GUIDELINES FOR THE CONDUCT OF TESTS FOR DISTINCTNESS, UNIFORMITY AND STABILITY Alternative Names:* Botanical name English French German Spanish Malus domestica Apple Pommier Apfel Manzano Borkh. The purpose of these guidelines (“Test Guidelines”) is to elaborate the principles contained in the General Introduction (document TG/1/3), and its associated TGP documents, into detailed practical guidance for the harmonized examination of distinctness, uniformity and stability (DUS) and, in particular, to identify appropriate characteristics for the examination of DUS and production of harmonized variety descriptions. ASSOCIATED DOCUMENTS These Test Guidelines should be read in conjunction with the General Introduction and its associated TGP documents. Other associated UPOV documents: TG/163/3 Apple Rootstocks TG/192/1 Ornamental Apple * These names were correct at the time of the introduction of these Test Guidelines but may be revised or updated. [Readers are advised to consult the UPOV Code, which can be found on the UPOV Website (www.upov.int), for the latest information.] i:\orgupov\shared\tg\applefru\tg 14 9 e.doc TG/14/9 Apple, 2005-04-06 - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. SUBJECT OF THESE TEST GUIDELINES..................................................................................................3 2. MATERIAL REQUIRED ...............................................................................................................................3 -

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

Germplasm Sets and Standardized Phenotyping Protocols for Fruit Quality Traits in Rosbreed

Germplasm Sets and Standardized Phenotyping Protocols for Fruit Quality Traits in RosBREED Jim Luby, Breeding Team Leader Outline of Presentation RosBREED Demonstration Breeding Programs Standardized Phenotyping Protocols Reference Germplasm Sets SNP Detection Panels Crop Reference Set Breeding Pedigree Set RosBREED Demonstration Breeding Programs Clemson U WSU Texas A&M UC Davis U Minn U Arkansas Rosaceae Cornell U WSU MSU MSU Phenotyping Affiliates USDA-ARS Driscolls Corvallis Univ of Florida UNH Standardized Phenotyping Protocols Traits and Standardized Phenotyping Protocols • Identify critical fruit quality traits and other important traits • Develop standardized phenotyping protocols to enable data pooling across locations/institutions • Protocols available at www.RosBREED.org Apple Standardized Phenotyping Firmness, Crispness – Instrumental, Sensory Sweetness, Acidity – Intstrumental, Sensory Color, Appearance, Juiciness, Aroma – Sensory At harvest Cracking, Russet, Sunburn Storage 10w+7d Storage 20w+7d Maturity Fruit size 5 fruit (reps) per evaluation Postharvest disorders Harvest date, Crop, Dropping RosBREED Apple Phenotyping Locations Wenatchee, WA St Paul, MN Geneva, NY • One location for all evaluations would reduce variation among instruments and evaluators • Local evaluations more sustainable and relevant for future efforts at each institution • Conduct standardized phenotyping of Germplasm Sets at respective sites over multiple (2-3) seasons • Collate data in PBA format, conduct quality control, archive Reference -

Cedar-Apple Rust

DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE RESEARCH & EXTENSION Agriculture and Natural Resources University of Arkansas System FSA7538 Cedar-Apple Rust Stephen Vann Introduction Assistant Professor One of the most spectacular Extension Urban Plant Pathologist diseases to appear in spring is cedar- apple rust. This disease is caused by the fungus Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae and requires both cedar and apple trees to survive each year. It is mainly a problem in the eastern portion of North America and is most important on apple or crab Figure 2. Cedar-apple rust on crabapple apple (Malus sp), but can also affect foliage. quince and hawthorn. yellow-orange color (Figures 1 and 2). Symptoms On the upper leaf surface of these spots, the fungus produces specialized The chief damage by this disease fruiting bodies called spermagonia. On occurs on apple trees, causing early the lower leaf surface (and sometimes leaf drop and poor quality fruit. This on fruit), raised hair-like fruiting bod can be a significant problem to com ies called aecia (Figure 3) appear as mercial apple growers but also harms microscopic cup-shaped structures. the appearance of ornamental crab Wet, rainy weather conditions favor apples in the home landscape. On severe infection of the apple. The apple, symptoms first appear as fungus forms large galls on cedar trees small green-yellow leaf or fruit spots in the spring (see next section), but that gradually enlarge to become a these structures do not greatly harm Arkansas Is Our Campus Visit our web site at: Figure 1. Cedar-apple rust (leaf spot) on Figure 3. Aecia of cedar-apple rust on https://www.uaex.uada.edu apple (courtesy J. -

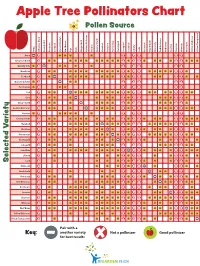

Apple Tree Pollinators Chart

Apple Tree Pollinators Chart Pollen Source Anna Arkansas Black Hills Beverly Braeburn Cortland Dorsett Golden Ein Shemer Fuji Gala Ginger Gold Golden Delicious Gordon Smith Granny Haralred Haralson Honeycrisp Honeygold Jonagold Jonathan Liberty Lodi McIntosh GoldOzark Lady Pink Red Delicious Red Rome Spartan Stayman Winesap River Wolf Delicious Yellow Transparent Yellow Anna Arkansas Black Beverly Hills Braeburn Cortland Dorsett Golden Ein Shemer Fuji Gala Ginger Gold Golden Delicious Gordon Granny Smith Haralred Haralson Honeycrisp Honeygold Jonagold Jonathan Liberty Lodi Selected Variety McIntosh Ozark Gold Pink Lady Red Delicious Red Rome Spartan Stayman Winesap Wolf River Yellow Delicious Yellow Transparent Pair with a Key: another variety Not a pollinizer Good pollinizer for best results Blueberry Shrub Pollinators Chart Pollen Source 3 in 1 Blueberry Biloxi Bluecrop Bluegold Blue Profusion Brightwell Duke Elliott Gupton Hardiblue Jersey Jubilee Misty Northcountry Northland Northsky O'Neal Lemonade Pink Polaris Blue Powder Reka Sharpblue Sunshine Blue Superior Tifblue Tophat 3 in 1 Blueberry (northern) Biloxi (southern) Bluecrop (northern) Bluegold (northern) Blue Profusion (northern) Brightwell (rabbiteye) Duke (northern) Elliott (northern) Gupton (southern) Hardiblue (northern) Jersey (northern) Jubilee (southern) Misty (southern) Northcountry (half-high) Northland (half-high) Northsky (half-high) Selected Variety O'Neal (southern) Pink Lemonade (rabbiteye) Polaris (half-high) Powder Blue (rabbiteye) Reka (northern) Sharpblue (southern) -

![Full Text [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9437/full-text-pdf-339437.webp)

Full Text [PDF]

® Fruit, Vegetable and Cereal Science and Biotechnology ©2011 Global Science Books Apple Breeding – From the Origin to Genetic Engineering Andreas Peil1* • Markus Kellerhals2 • Monika Höfer1 • Henryk Flachowsky1 1 Julius Kühn-Institut - Federal Research Centre for Cultivated Plants (JKI), Institute for Breeding Research on Horticultural and Fruit Crops, Pillnitzer Platz 3a, D-01326 Dresden, Germany 2 Swiss Federal Research Station Agroscope Changins-Wädenswil, CH-8820 Wädenswil, Switzerland Corresponding author : * [email protected] ABSTRACT Apple is the most important temperate fruit crop and ranks fourth in world production of fruits after citrus, grapes and bananas. Although more than 10,000 cultivars are documented, only a few dozen are grown on a commercial scale worldwide. Despite the abundant number of cultivars there is a demand for new cultivars better adapted to climatic conditions/changes and sustainable production. Yet, the challenge for apple breeding is the establishment of improved, multiple disease resistant cultivars with high and regularly yield suited for modern production systems. Due to the fast development of molecular techniques an increasing knowledge on the genome of apple is available, e.g. the whole genome sequence of ‘Golden Delicious’ (Velasco et al. 2010). Molecular markers for a lot of major traits, mostly resistance genes, and QTLs facilitate marker assisted selection, especially the pyramiding of resistance genes to achieve more durable resistance. Mainly the breakdown of the Rvi6 (Vf) scab resistance enhanced the breeding for pyramided resistance genes. But nevertheless, until now there is a gap between the existing molecular knowledge and its application in apple breeding. This paper will focus on the origin and domestication of apple, breeding objectives and classical as well as molecular approaches to achieve breeding aims. -

The Pathogenicity and Seasonal Development of Gymnosporangium

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1931 The ap thogenicity and seasonal development of Gymnosporangium in Iowa Donald E. Bliss Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, Botany Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Bliss, Donald E., "The ap thogenicity and seasonal development of Gymnosporangium in Iowa " (1931). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14209. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14209 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. -

Tasting Room Bottle Menu V8 Front

Bottles Available: 375ml - $12 750ml - $18 Semi-dry Medium Semi-Sweet PRESSED, FERMENTED, AND BOTTLED IN AURORA, CO www.HaykinFamilyCider.Com Masonville Orchards Seasonal Series Dry Summer [6.6% ABV] - Masonville Orchards,CO - On the Front Range, summer apples ripen in July and August. Their flavors tend toward a lively and sprightly acidity. This cider is evocative of summer with bright fruity notes of vanilla and fresh apple. This blend includes dozens of summer varieties, Including William’s Pride, Akane, Pristine, Sansa, Redfree and others. 2018 SILVER medal winner at GLINTCAP Semi-Dry Early Fall [7.7% ABV] - Masonville Orchards, CO - This cider is made from apples that ripen in early fall at Masonville Orchards. There are dozens of varieties of apples in this blend including Wolf River, Lamb Abbey Pearmain, Kinderkrisp, Cortland and others. The cider is rich and creamy with soft and round fruity qualities. Medium Late Fall [6.3% ABV] - Masonville Orchards, CO - This cider is made from apples that ripen in late fall at Masonville Orchards. There are dozens of varieties of apples in this blend including Jonathan, Ruby Jon, Ozark Gold, Honeycrisp, Empire, Jonagold, Bella. This cider is rich yet delicate with lemon and raspberry tartness. 2018 SILVER medal winner at GLINTCAP Semi-Sweet Winter [6.4% ABV] - Masonville Orchards, CO - This cider is made from the last apples to ripen at Masonville Orchards. There are dozens of varieties of apples in this blend including Goldrush, Arkansas Black, Rome Beauty, Charlie's Gold and others. The cider has a big complex vanilla and fruit-filled aroma. -

Fruit, Nut & Grape Varieties for the Contra Costa Home Orchard

ccmg.ucanr.edu February 2020 Fruit, Nut & Grape Varieties for the Contra Costa Home Orchard by Janet Caprile, Contra Costa County Farm Advisor Emeritus NOTES: The County has been divided into 4 climate zones based on those outlined in the Sunset Western Garden Book. The zones include: Zone 17: Coastal strips Kensington San Pablo Rodeo (bayside) El Cerrito Pinole (bayside) Crockett Richmond Hercules (bayside) Zone 16: Northern California coast thermal belts Orinda (far west) Zone 15: Chilly winters areas along the Coast Range Orinda (central) Martinez (central & west) Walnut Creek (most) El Sobrante Pacheco Alamo (east of Hwy 680) Pinole (inland) Pleasant Hill Danville ( most) Hercules (inland) Concord (most) Rodeo (inland) Clayton Zone 14: Northern California’s inland area with some ocean influence Pittsburg Orinda (east) Alamo (west of Hwy 680) Antioch Moraga Danville (part) Oakley Lafayette Blackhawk Brentwood Walnut Creek (west of Hwy 680) San Ramon Discovery Bay Concord (part) Byron Martinez ( east) Refer to this Sunset website to find your “zone”: https://www.sunset.com/garden/climate-zones/sunset-climate-zone- bay-area LEGEND: COMMONLY GROWN AND COMMONLY AVAILABLE VARIETIES SHOWN IN BOLDFACE TYPE. Parentheses indicate zones that may support the listed fruit variety but are not ideal. v-2020-02-27 1 of 18 The University of California prohibits discrimination or harassment of any person in any of its programs or activities. See the complete Nondiscrimination Statement at ucanr.edu. ccmg.ucanr.edu Fruit, Nut & Grape Varieties for the Contra Costa Home Orchard February 2020 ALMOND Almonds have a low chill requirement (200-300 hours) but need summer heat to mature a crop. -

Treeid Variety Run 2 DNA Milb005 American Summer Pearmain

TreeID Variety Run 2 DNA Run 1 DNA DNA Sa… Sourc… Field Notes milb005 American Summer Pearmain/ "Sara's Polka American Summer Pearmain we2g016 AmericanDot" Summer Pearmain/ "Sara's Polka American Summer Pearmain we2f017 AmericanDot" Summer Pearmain/ "Sara's Polka American Summer Pearmain we2f018 AmericanDot" Summer Pearmain/ "Sara's Polka American Summer Pearmain eckh001 BaldwinDot" Baldwin-SSE6 eckh008 Baldwin Baldwin-SSE6 2lwt007 Baldwin Baldwin-SSE6 2lwt011 Baldwin Baldwin-SSE6 schd019 Ben Davis Ben Davis mild006 Ben Davis Ben Davis wayb004 Ben Davis Ben Davis andt019 Ben Davis Ben Davis ostt014 Ben Davis Ben Davis watt008 Ben Davis Ben Davis wida036 Ben Davis Ben Davis eckg002 Ben Davis Ben Davis frea009 Ben Davis Ben Davis frei009 Ben Davis Ben Davis frem009 Ben Davis Ben Davis fres009 Ben Davis Ben Davis wedg004 Ben Davis Ben Davis frai006 Ben Davis Ben Davis frag004 Ben Davis Ben Davis frai004 Ben Davis Ben Davis fram006 Ben Davis Ben Davis spor004 Ben Davis Ben Davis coue002 Ben Davis Ben Davis couf001 Ben Davis Ben Davis coug008 Ben Davis Ben Davis, error on DNA sample list, listed as we2a023 Ben Davis Bencoug006 Davis cria001 Ben Davis Ben Davis cria008 Ben Davis Ben Davis we2v002 Ben Davis Ben Davis we2z007 Ben Davis Ben Davis rilcolo Ben Davis Ben Davis koct004 Ben Davis Ben Davis koct005 Ben Davis Ben Davis mush002 Ben Davis Ben Davis sc3b005-gan Ben Davis Ben Davis sche019 Ben Davis, poss Black Ben Ben Davis sche020 Ben Davis, poss Gano Ben Davis schi020 Ben Davis, poss Gano Ben Davis ca2e001 Bietigheimer Bietigheimer/Sweet -

Handling of Apple Transport Techniques and Efficiency Vibration, Damage and Bruising Texture, Firmness and Quality

Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences PUBLISHED BY: B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ACTIVITIES OF WP9 IN THE CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE AGROPHYSICS CONTRACT NO: QLAM-2001-00428 CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR APPLIED PHYSICS IN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE WITH THE th ACRONYM AGROPHYSICS IS FOUNDED UNDER 5 EU FRAMEWORK FOR RESEARCH, TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT AND DEMONSTRATION ACTIVITIES GENERAL SUPERVISOR OF THE CENTRE: PROF. DR. RYSZARD T. WALCZAK, MEMBER OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES PROJECT COORDINATOR: DR. ENG. ANDRZEJ STĘPNIEWSKI WP9: PHYSICAL METHODS OF EVALUATION OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLE QUALITY LEADER OF WP9: PROF. DR. ENG. BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI, JR. REVIEWED BY PROF. DR. ENG. JÓZEF KOWALCZUK TRANSLATED (EXCEPT CHAPTERS: 1, 2, 6-9) BY M.SC. TOMASZ BYLICA THE RESULTS OF STUDY PRESENTED IN THE MONOGRAPH ARE SUPPORTED BY: THE STATE COMMITTEE FOR SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNDER GRANT NO. 5 P06F 012 19 AND ORDERED PROJECT NO. PBZ-51-02 RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF POMOLOGY AND FLORICULTURE B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ©Copyright by BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES LUBLIN 2006 ISBN 83-89969-55-6 ST 1 EDITION - ISBN 83-89969-55-6 (IN ENGLISH) 180 COPIES, PRINTED SHEETS (16.8) PRINTED ON ACID-FREE PAPER IN POLAND BY: ALF-GRAF, UL. -

Brazoria County Master Gardener Association 2013 Citrus and Fruit Guide

BRAZORIA COUNTY MASTER GARDENER ASSOCIATION 2013 CITRUS AND FRUIT GUIDE A Guide to Proper Selection and Planting Tips for Brazoria County Gardeners B.E.E.S—Brazoria Environmental Education Station B- Be aware of the environment E- Endeavor to protect our natural resources E- Educate our community S- Serve as stewards of the Earth FOREWORD The Brazoria County Master Gardener (BCMG) program is part of the state organization affiliated with the Texas A & M Extension System. We are a 501C3 organization under IRS statutes. Monies collected from this sale supports the B.E.E.S. educational and demonstration gardens located at the end of CR 171. One of this years’ major projects is to build walkways which meet handicap standards and for our senior citizens. The gardens are open on Tuesdays and Fri- days to the public. Special topic programs are offered on Saturdays for public attendance and are advertised in local newspapers and radio. The gardens include eating fruits (berries, fruit, etc.), herb garden, tropicals, veggies, rose garden, two greenhouses other demo/experimental plants. The contents of this brochure utilized multiple resources from leading agricultural universities, Texas and other state and national organizations. Fruit plants are selected on basis of Master Gardener feedback in our county as well as neighbor counties. Past demand & interviews of folks after each years’ February sale help us select new varieties and determine plant volume each year at the sale. BCMG makes genuine efforts to provide the public with information on plants offered. Other than assuring the public that we use only licensed nurseries, BCMG cannot assure success.