Avoiding Coping with Surprise in Great Power Conflicts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

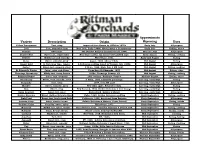

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

Bramble Volume 21, Issue 3

VOLUME 21, ISSUE 3 THE BRAMBLE AUTUMN, 2005 THE NEWSLETTER OF THE NORTH AMERICAN BRAMBLE GROWERS ASSOCIATION, INC. Request for Proposals ***** NABGA Annual Meeting & Conference ***** The North American Bramble Growers January 5-6, 2006 – Savannah, Georgia Research Foundation (NABGRF) is Our 2006 Annual Meeting will be held in association with the Georgia Fruit and seeking proposals for bramble research Vegetable Growers Association’s Southeast Fruit and Vegetable Conference (SFVC) in for the year 2006. Since 1999, NABGRF Savannah, Georgia. We hope to see you there! Watch your mailbox and e-mail for has funded a total of 26 proposals, registration details and accommodations information. totaling $50,146. To register for NABGA’s meeting, you will simply register for the SFVC. This All bramble proposals will be conference has a very large trade show and extensive sessions on blueberries, peaches, considered, however preference will be and vegetable crops January 6-8. Fees are very reasonable and both one-day and three- given to proposals related to: day registrations are available. The North American Strawberry Growers Association • cultivar development and testing (NASGA) will be meeting here (as the “North American Berry Conference”), on • pest management strategies January 4-6, with educational sessions on the 4th, a tour on January 5, and general • cultural management strategies to im- sessions the morning of the 6th. A forum on the National Berry Crops Initiative prove yield, quality and profitability Strategic Plan for the Berry Industry (see pages 8-9) is planned for Saturday, January • identification of beneficial com- 7. This concentration and combination of oppportunities is well worth the trip. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

KIIS DENMARK, Summer 2018

KIIS DENMARK, Summer 2018 HIST 490 Viking Age to Modern State Instructor: Dr. Carolyn Dupont Contact information: [email protected] Course Description, Objectives, and Content: This course will explore the broad sweep of Danish history. We will explore daily life in Viking society, Viking religion and culture, and, of course, the Viking exploits abroad. We will examine in detail the transformation of Denmark from a pagan, Viking society to a modern Christian state. Training our lens on more recent times, we examine Danish society and Denmark’s role in global affairs at the height of its power in the 16th century. In the final sessions, we will look at the occupation of Denmark by the Germans during World War II, as well as Denmark’s astounding rescue of its Jewish population. Students should be very aware that the course will not proceed chronologically. We will move back and forth among the various historical eras, because we want to take advantage of historical sites that cannot necessarily be visited in chronological order. Student Learning Outcomes: Upon completion of this course, students will be able to: 1) Describe and explain the major facets of Viking society 2) Describe and explain the reason for the Vikings’ ultimate embrace of Christianity 3) Identify and describe key turning points and trends in Danish history 4) Identify and describe how the major events and trends in modern European history have unfolded in Denmark 5) Demonstrate an understanding of how perspective and vantage point shape the telling of history 6) Critically evaluate the role played by perspective and vantage point at sites where Denmark’s history is told Readings (all readings will be provided by the instructor and placed in a Dropbox folder) Excerpts from Knud J.V. -

Survey of Apple Clones in the United States

Historic, archived document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. 5 ARS 34-37-1 May 1963 A Survey of Apple Clones in the United States u. S. DFPT. OF AGRffini r U>2 4 L964 Agricultural Research Service U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE PREFACE This publication reports on surveys of the deciduous fruit and nut clones being maintained at the Federal and State experiment stations in the United States. It will b- published in three c parts: I. Apples, II. Stone Fruit. , UI, Pears, Nuts, and Other Fruits. This survey was conducted at the request of the National Coor- dinating Committee on New Crops. Its purpose is to obtain an indication of the volume of material that would be involved in establishing clonal germ plasm repositories for the use of fruit breeders throughout the country. ACKNOWLEDGMENT Gratitude is expressed for the assistance of H. F. Winters of the New Crops Research Branch, Crops Research Division, Agricultural Research Service, under whose direction the questionnaire was designed and initial distribution made. The author also acknowledges the work of D. D. Dolan, W. R. Langford, W. H. Skrdla, and L. A. Mullen, coordinators of the New Crops Regional Cooperative Program, through whom the data used in this survey were obtained from the State experiment stations. Finally, it is recognized that much extracurricular work was expended by the various experiment stations in completing the questionnaires. : CONTENTS Introduction 1 Germany 298 Key to reporting stations. „ . 4 Soviet Union . 302 Abbreviations used in descriptions .... 6 Sweden . 303 Sports United States selections 304 Baldwin. -

1 the Evolution of Blogs the Political Blogosphere Has Changed a Lot

The Evolution of Blogs The political blogosphere has changed a lot since I first starting blogging. Six years ago I set up a little blog to chronicle my life in New York City. The intended audience for the blog was my husband, who read it in the office while chomping on a bologna sandwich at lunch. I had no grand designs of becoming a media celebrity or single handedly taking down the newspaper industry or changing the course of American politics – which is a good thing, because that never happened. I wanted to write stuff about my kids, my job, and political events that were tied to my academic pursuits. My first posts were about a roof party in the city and the trials of doing laundry in a fourth floor walk-up. After a few months, I began to write more substantive posts and linked to other bloggers. They linked back to me, and I gained a modest audience. I networked with bigger name bloggers and gained a deeper understanding of blogging practices. I learned how to write a post that would get noticed by others, how to keep my cool when a crackpot attacked me, and how to avoid writing snarky posts about friends and family. Blogging became a big part of my life. I spent nearly five hours of every weekday writing blog posts, reading other people’s blogs, monitoring traffic sources, looking for blog fodder, and responding to e-mails from readers. I blogged while my kids napped and after teaching classes at Hunter College. I blogged instead of watching television. -

An Old Rose: the Apple

This is a republication of an article which first appeared in the March/April 2002 issue of Garden Compass Magazine New apple varieties never quite Rosaceae, the rose family, is vast, complex and downright confusing at times. completely overshadow the old ones because, as with roses, a variety is new only until the next This complexity has no better exemplar than the prince of the rose family, Malus, better known as the variety comes along and takes its apple. The apple is older in cultivation than the rose. It presents all the extremes in color, size, fragrance place. and plant character of its rose cousin plus an important added benefit—flavor! One can find apples to suit nearly every taste and cultural demand. Without any special care, apples grow where no roses dare. Hardy varieties like the Pippins, Pearmains, Snow, Lady and Northern Spy have been grown successfully in many different climates across the U.S. With 8,000-plus varieties worldwide and with new ones introduced annually, apple collectors in most climates are like kids in a candy store. New, Favorite and Powerhouse Apples New introductions such as Honeycrisp, Cameo and Pink Lady are adapted to a wide range of climates and are beginning to be planted in large quantities. The rich flavors of old favorites like Spitzenburg and Golden Russet Each one is a unique eating experience that are always a pleasant surprise for satisfies a modern taste—crunchy firmness, plenty inexperienced tasters. of sweetness and tantalizing flavor. Old and antique apples distinguish These new varieties show promise in the themselves with unusual skin competition for the #1 spot in the world’s colors and lingering aftertastes produce sections and farmers’ markets. -

Cold Damage Cultivar Akero 0 Albion 0 Alexander 0 Alkmene 0 Almata 0

Cold Damage Table 16 1. less than 5% Bud 118 0 2. 5-15% Bud 9 on Ranetka 0 3. More than 15%. Cultivar 4. severe (50% ) Carroll 0 Akero 0 Centennial 0 Albion 0 Chehalis 0 Alexander 0 Chestnut Crab 0 Alkmene 0 Collet 0 Almata 0 Collins 0 American Beauty 0 Crab 24 false yarlington 0 Anaros 0 Cranberry 0 Anoka 0 Croncels 0 Antonovka 81 0 Dan Silver 0 Antonovka 102 0 Davey 0 Antonovka 109 0 Dawn 0 antonovka 52 0 Deane 0 Antonovka 114 0 Dolgo (grafted) 0 Antonovka 1.5 0 Douce Charleviox 0 Antonovka 172670-B 0 Duchess 0 Antonovka 37 0 Dudley 0 Antonovka 48 0 Dudley Winter 0 Antonovka 49 0 Dunning 0 Antonovka 54 0 Early Harvest 0 Antonovka Debnicka 0 Elstar 0 Antonovka Kamenichka 0 Equinox 0 Antonovka Monasir 0 Erwin Bauer 0 Antonovka Shafrain 0 Fameuse 0 Aroma 0 Fantazja 0 Ashmead's Kernal 0 Fox Hill 0 Audrey 0 Frostbite TM 0 Autumn Arctic 0 Garland 0 Baccata 0 Geneva 0 Banane Amere 0 Gideon 0 Beacon 0 Gilpin 0 Beautiful Arcade 0 Gingergold 0 Bedford 0 Golden Russet 0 Bessemianka Michurina 0 Granny Smith Seedling 0 Bilodeau 0 Green Peak 0 Black Oxford 0 Greenkpeak 0 Blue Pearmain 0 Greensleeves 0 Borovitsky 0 Haralred 0 Breaky 0 Haralson 0 Cold Damage Table 16 1. less than 5% McIntosh 0 2. 5-15% Melba 0 3. More than 15%. Cultivar 4. severe (50% ) Miami 0 Harcourt 0 Minnehaha 0 Hawaii 0 MN 85-22-99 0 Herring's Pippin 0 MN 85-23-21 0 Hewe's Crab 0 MN 85-27-43 0 Hiburnal 0 Morden 0 Honeygold 0 Morden 359 0 Hyslop Crab 0 Niedzwetzkyana 0 Island Winter 0 No Blow 0 Jersey Mac 0 Noran 0 Jonamac 0 Noret 0 Jonathan 0 Norhey 0 Kazakh 1 0 Norland 0 Kazakh -

Download The

RANKING THE BEST THE FUTURE LOOKS MARCIA MOFFAT YOUR EMPLOYEES BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS BRIGHT FOR OLD-SCHOOL ON BLACKROCK’S BIG LOVE MESSAGING APPS— BRANDS IN CANADA NEWSLETTERS CLIMATE PUSH WHY DON’T YOU? DEATH-DEFYING FEATS OF FINANCIALFINANCIAL ACRO∂BATICS! MIND-BOGGLING LOGISTICAL∑ LEAPS! CLOWNS, PPOLOLAR BEARS AND AN UNLIKELY NEW RINGMASTER INSIDE THE YEAR THAT NEARLY KILLED CIRQUE DU SOLEIL AND ITS PLAN FOR A POST-PANDEMIC COMEBACK JUNE 2021 VISIONARIES Fancygoggles aside, the reality before our eyesisthat Calgary is an opportunity-rich city.Weare home to innovators, dreamers and problem solvers whose signatureentrepreneurial spirit allowthem to see opportunity whereothers might not. These visionaries are turning heads across all of our sectors each and every day. They embody the vision forour city and arehelping put Calgary and our innovation ecosystem on the global map as aplace wherepeople come to solvesome of the world’sgreatest challenges. With the breadth of our talented people and thestrength of our community,the opportunities in Calgary arelimitless. Take acloser look at Calgary’svisionaries at livetechlovelife.com/stories Calgary: Canada’smostadventurous tech city.TM Contents 2 EDITOR’S NOTE THE SHOW WILL GO ON When the world shut down, so did Cirque du Soleil. We followed it 4 SEVEN THINGS 16 through the logistical nightmare the followed, its filing for creditor Want to save the planet? protection, the dramatic battle for ownership and how it’s preparing Get a mascot. Plus, why to return to the stage. /By Jason Kirby banking jobs still rule and professional wrestling rocks STRIKE UP THE BRANDS Our first annual ranking of 25 companies that define what business- 7 NEED TO KNOW 30 Researchers are working on to-business excellence looks like right now. -

Lies, Incorporated

Ari Rabin-Havt and Media Matters for America Lies, Incorporated Ari Rabin-Havt is host of The Agenda, a national radio show airing Monday through Friday on SiriusXM. His writing has been featured in USA Today, The New Republic, The Nation, The New York Observer, Salon, and The American Prospect, and he has appeared on MSNBC, CNBC, Al Jazeera, and HuffPost Live. Along with David Brock, he coauthored The Fox Effect: How Roger Ailes Turned a Network into a Propaganda Machine and The Benghazi Hoax. He previously served as executive vice president of Media Matters for America and as an adviser to Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid and former vice president Al Gore. Media Matters for America is a Web-based, not-for-profit, progressive research and information center dedicated to comprehensively monitoring, analyzing, and correcting conservative misinformation in the U.S. media. ALSO AVAILABLE FROM ANCHOR BOOKS Free Ride: John McCain and the Media by David Brock and Paul Waldman The Fox Effect: How Roger Ailes Turned a Network into a Propaganda Machine by David Brock, Ari Rabin-Havt, and Media Matters for America AN ANCHOR BOOKS ORIGINAL, APRIL 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Ari Rabin-Havt and Media Matters for America All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Reinhart-Rogoff chart on this page created by Jared Bernstein for jaredbernsteinblog.com. -

Cuaderno De Documentacion

SECRETARIA DE ESTADO DE ECONOMÍA, MINISTERIO SECRETARÍA GENERAL DE POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA DE ECONOMÍA Y ECONOMÍA INTERNACIONAL Y HACIENDA SUBDIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE ECONOMÍA INTERNACIONAL CUADERNO DE DOCUMENTACION Número 91º ANEXO XI Alvaro Espina Vocal Asesor 6 de Septiembre de 2010 BACKGROUND0BU PAPERS: 1. A1B Keynesian success story, Spiegel On Line…7 2. The2B Economist as policitcal philosopher, Economicprincipals.com by David Warsh…13 3. What3B Germany knows about debt, The New York Times by Tyler Cowen…15 4. Germany’s4B super competitiveness: a helping hand from eastern Europe, Vox by Dalia Marin…17 5. Krugman5B on Cowen and Germany, Marginal Revolution, by Paul Krugman…19 6. What’s6B Germany’s secret?, The Economist, by Tyler Cowen…21 7. A7B generation of overoptimistic equity analysts, McKinsey Quarterly…23 8. Equity8B analysts: Still too bullish, Mckinsey&Company by Marc Goedhart, Rishi Raj and Abhishek Saxena…24 9. Bundesbank9B says Ireland will destroy eurozone, Eurointelligence…28 10. Senate10B set to end stalemate and extend jobless aid, The New York Times by Carl Hulse…31 11. Euro1B back at $1.30, Eurointelligence…34 12. Part12B 5A. What happens if things go really badly? $15 trillion of sovereign debt in default, Calculated Risk …37 13. The13B pundit delusion, The New York Times by Paul Krugman…40 14. Why14B I worry, The Conscience of a Liberal by Goldman Sachs…41 15. Whay15B the battle is joined over tightening, Ft.com by Martin Wolf…51 16. The16B great austerity debate, Ft.com …53 17. It17B is far too soon to end expansion by Brad Delong…55 18. Today’s18B Keynesians have learnt nothing, Ft.com by Niall Ferguson…57 19.