Argent a Cross Gules. the Origins and English Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ing Items Have Been Registered

ACCEPTANCES Page 1 of 37 June 2017 LoAR THE FOLLOWING ITEMS HAVE BEEN REGISTERED: ÆTHELMEARC Alrekr Bergsson. Device. Per saltire gules and sable, in pale two wolf’s heads erased and in fess two sheaves of arrows Or. Brahen Lapidario. Name and device. Argent, a lozenge gules between six French-cut gemstones in profile, two, two and two azure, a base gules. The ’French-cut’ is a variant form of the table cut, a precursor to the modern brilliant cut. It dates to the early 15th Century, according to "Diamond Cuts in Historic Jewelry" by Herbert Tillander. There is a step from period practice for gemstones depicted in profile. Hrólfr á Fjárfelli. Device. Argent estencely sable, an ash tree proper issuant from a mountain sable. Isabel Johnston. Device. Per saltire sable and purpure, a saltire argent and overall a winged spur leathered Or. Lisabetta Rossi. Name and device. Per fess vert and chevronelly vert and Or, on a fess Or three apples gules, in chief a bee Or. Nice early 15th century Florentine name! Símon á Fjárfelli. Device. Azure, a drakkar argent and a mountain Or, a chief argent. AN TIR Akornebir, Canton of. Badge for Populace. (Fieldless) A squirrel gules maintaining a stringless hunting horn argent garnished Or. An Tir, Kingdom of. Order name Order of Lions Mane. Submitted as Order of the Lion’s Mane, we found no evidence for a lion’s mane as an independent heraldic charge. We therefore changed the name to Order of _ Lions Mane to follow the pattern of Saint’s Name + Object of Veneration. -

Sign of the Son of Man.”

Numismatic Evidence of the Jewish Origins of the Cross T. B. Cartwright December 5, 2014 Introduction Anticipation for the Jewish Messiah’s first prophesied arrival was great and widespread. Both Jewish and Samaritan populations throughout the known world were watching because of the timeframe given in Daniel 9. These verses, simply stated, proclaim that the Messiah’s ministry would begin about 483 years from the decree to rebuild Jerusalem in 445BC. So, beginning about 150 BC, temple scribes began placing the Hebrew tav in the margins of scrolls to indicate those verses related to the “Messiah” or to the “Last Days.” The meaning of the letter tav is “sign,” “symbol,” “promise,” or “covenant.” Shortly after 150 BC, the tav (both + and X forms) began showing up on coins throughout the Diaspora -- ending with a flurry of the use of the symbol at the time of the Messiah’s birth. The Samaritans, in an effort to remain independent of the Jewish community, utilized a different symbol for the anticipation of their Messiah or Tahib. Their choice was the tau-rho monogram, , which pictorially showed a suffering Tahib on a cross. Since the Northern Kingdom was dispersed in 725 BC, there was no central government authority to direct the use of the symbol. So, they depended on the Diaspora and nations where they were located to place the symbol on coins. The use of this symbol began in Armenia in 76 BC and continued through Yeshua’s ministry and on into the early Christian scriptures as a nomina sacra. As a result, the symbols ( +, X and ) were the “original” signs of the Messiah prophesied throughout scriptures. -

Lesson 4 – Is Sir Gawain a Typical Knight? Can You Make Accurate

Lesson 4 – Is Sir Gawain a typical knight? Can you make accurate comments on the hidden meaning of language? Send work to your teacher via Google Classroom, Google Drive or email. Activity 1 Use the correct key word in the sentences below. Each word can only be used once. brutish savage formidable virtuous integrity paragon obligation a) The Miller lacked _______________ as he would steal corn and over-charge for it. b) I know the Green Knight is a _______________ character because when he arrives on his large, armoured war horse everyone is speechless. c) The Green Knight’s challenge suggested he was a ______________ person who did not follow the normal rules of society. d) The policeman praised the _____________ person who had returned the wallet of cash. e) A knight has an _______________ to protect his king and kingdom. f) When Sir Gawain volunteers, he is a ______________ of virtue and honour. g) The ______________ lion could not be stopped from attacking the young gazelles. Activity 2 Read the extract from page 56-63 about Gawain’s journey to the Green Chapel. Always above and ahead of him flew a flock of geese, pointing the way north, a guiding arrowhead in the sky. It was the route Gawain knew he must follow, that would lead him, sooner or later, to the place he most dreaded on this earth... the Chapel of the Green Knight. Despite the deep bitter winter, Gawain rode on through the wastelands alone, always keeping the flying geese ahead of him and the wild mountains of Wales to his left. -

Sideless Surcoats and Gates of Hell: an Overview of Historical Garments and Their Construction by Sabrina De La Bere

Sideless Surcoats and Gates of Hell: an Overview of Historical Garments and their Construction by Sabrina de la Bere Some were sleeve- less and some not. Menʼs came in vary- ing lengths and may be split for riding. In the 14th C womenʼs had a very long and wide skirt. Herjolfsnes 37 (right) is thought to be a mans surcoat from the 14th C. It has relatively small arm holes. Below is a page from the Luttrell Psalter showing Sir Geoffrey Luttrell being attend- ed by his wife Agnes de Sutton and daugh- ter in law Beatrice le Scrope. Both are wearing sideless sur- Source: Time Life pg. 79 coats that bear their Many myths have grown up around the sideless sur- Herjolfsnes 37 heraldic arms. There coat. This class will look at what is known and what is http://www.forest.gen.nz/Medieval/ is great debate in cos- articles/garments/H37/H37.html speculation. We will look at how the surcoat evolved t u m i n g in its 200 years of use by men and women. Lastly we circles, as will discuss how to construct one of each of the major to whether styles. This handout is designed to be used in the con- such he- text of the class. raldic sur- Cloaks and overtunics of various designs exist from coats ex- earliest history. Where the sleeveless surcoat originates isted and, is unknown, but it begins its known popularity in the if they did, 12th Century. were they In the picture above, a knight on Crusade has an over a limited tunic. -

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

British Royal Banners 1199–Present

British Royal Banners 1199 – Present Geoff Parsons & Michael Faul Abstract The presentation begins with the (accepted) date of 1199, the death of King Richard I, the first king known to have used the three gold lions on red. It continues to show how King Edward III added the French Royal Arms, consequent to his claim to the French throne. There is then the change from “France Ancient” to “France Modern” by King Henry IV in 1405, which set the pattern of the arms and the standard for the next 198 years. The story then proceeds to show how, over the ensuing 234 years, there were no fewer than six versions of the standard until the adoption of the present pattern in 1837. The presentation includes pictures of all the designs, noting that, in the early stages, the arms appeared more often as a surcoat than a flag. There is also some anecdotal information regarding the various patterns. Anne (1702–1714) Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 799 British Royal Banners 1199 – Present Figure 1 Introduction The presentation begins with the (accepted) date of 1199, the death of King Richard I, the first king known to have used the three gold lions on red. Although we often refer to these flags as Royal Standards, strictly speaking, they are not standard but heraldic banners which are based on the Coats of Arms of the British Monarchs. Figure 2 William I (1066–1087) The first use of the coats of arms would have been exactly that, worn as surcoats by medieval knights. -

Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard (2012)

FGDC-STD-018-2012 Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard Marine and Coastal Spatial Data Subcommittee Federal Geographic Data Committee June, 2012 Federal Geographic Data Committee FGDC-STD-018-2012 Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard, June 2012 ______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objectives ................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Need ......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Scope ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Application ............................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Relationship to Previous FGDC Standards .............................................................. 4 1.6 Development Procedures ......................................................................................... 5 1.7 Guiding Principles ................................................................................................... 7 1.7.1 Build a Scientifically Sound Ecological Classification .................................... 7 1.7.2 Meet the Needs of a Wide Range of Users ...................................................... -

Saint George PROPERTY SUMMARY Place, a 230,000 SF Premier Shopping and Dining Destination & HIGHLIGHTS Located in Saint George, Utah

SAINT GPlaceEORGE SAINT GPlaceEORGE JEFFFALL MITCHELL 2022 [email protected] West direct 702.374.0211Commercial Real Estate Jeffrey Mitchell - 702.374.0211 FALL 2022 View [email protected] Babcock Design SCOTT 801.531.1144BRADY // www.babcockdesign.com Mountain West R&O Construction [email protected] // www.randoco.com direct 801.456.8804Utah License # 292934-5501 View Profile Commercial Real Estate JOE COOLEY Jeffrey Mitchell - 702.374.0211 [email protected] [email protected] direct 801.456.8803 View Profile Babcock Design 801.531.1144 // www.babcockdesign.com RETAIL - INVESTMENT - INDUSTRIAL - LAND - OFFICE - URBAN - MULTIFAMILY - HOSPITALITY Best Commercial Real Estate 312 East South Temple | Salt Lake City, Utah 84111 | Office 801.456.8800 | www.mtnwest.com Of Southern Utah This statement with the information it contains is given with the understanding that all negotiations relating to the purchase, renting or leasing of the property described above shall be conducted through this office. The above information while not guaranteed has been secured from sources we believe to be reliable. R&O Construction 801.627.1403 // www.randoco.com Utah License # 292934-5501 We are excited to announce the redevelopment of Saint George PROPERTY SUMMARY Place, a 230,000 SF premier shopping and dining destination & HIGHLIGHTS located in Saint George, Utah. Saint George Place is located at the intersection of 700 South PROPERTY INFORMATION – PHASE I – and Bluff Street and is uniquely placed in the center of the REDEVELOPMENT OF CURRENT SHOPPING CENTER Southern Utah. The original property was constructed in the 717 – 899 S Bluff Street PROPERTY ADDRESS St. George, UT 84770 1990’s and has seen little change since - everything is being ACREAGE 19.99 acres redesigned from elevations, landscaping, parking lots, lighting REDEVELOPMENT SF 230,150 SF and restaurant spaces with drive-thru and patios. -

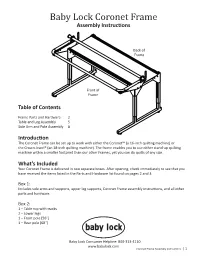

Coronet (BLCT16) Frame Assembly Instructions REVISED

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 REVISIONS ECO REV. DESCRIPTION DATE APPROVED A INITIAL RELEASE D D Baby Lock Coronet Frame Assembly Instructions Back of Frame C C Front of Frame Table of Contents Frame Parts and Hardware 2 BILL OF MATERIALS ENG-10007 Table and Leg Assembly 5 ITEM PART NUMBER DESCRIPTION QTY. Side Arm and Pole Assembly 8 1 QF05300-300 TABLE ASSY, TACONY FRAME 1 2 QF05300-402 CORNER HEIGHT BAR, A 2 B Introduction 3 QF05300-403 CORNER HEIGHT BAR, B 2 B The Coronet Frame can be set up to work with either the Coronet™ (a 16-inch quilting machine) or 4 QF05300-401 END LEG STAND 2 the Crown Jewel® (an 18-inch quilting machine). The frame enables you to use either stand-up quilting 5 QF09318-303 SCREW-M6x12 SWH 6 machine within a smaller footprint than our other Frames, yet you can do quilts of any size. 6 QF09318-07 Screw-M8x16 SBHCS 16 7 QF09318-108 LEVELING GLIDE 4 What’s Included 8 ENG-10005 ASSY-SIDE ARM RIGHT LF 1 Your Coronet Frame is delivered in two separate boxes. After opening, check immediately to see that you 9 ENG-10006 ASSY-SIDE ARM LEFT LF 1 have received the items listed in the Parts and Hardware list found on pages 2 and 3. 10 QF10005 POLE FRONT LF 1 11 QF10009 POLE REAR LF 1 Box 1: 12 QF10011 END CAP-REAR POLE LF 2 Includes side arms and supports, upper leg supports, Coronet Frame assembly instructions, and all other UNLESS OTHERWISE SPECIFIED: NAME DATE parts and hardware. -

Lochac Pursuivant Extraordinary Exam

Lochac Pursuivant Extraordinary Exam October 2010, A.S. 45 In the space provided please give your SCA name; also the blazon and emblazon of your current device, even if not yet registered. [This is not a marked question] THIS IS AN OPEN BOOK EXAM . The intent of this exam is to test your ability to locate answers and apply the rules of SCA heraldry, rather than your ability to memorise information. You are permitted to utilise any and all books, websites, and SCA publications at your disposal. You are NOT permitted to simply ask another herald, an email list or forum for the answer. Be wary when consulting modern heraldic texts. Send your completed exam to [email protected] , or by post to the current Crux Australis Herald at: Talith Jennison 4/25 Goble St. Niddrie Vic. 3042 Australia Please do not send mail requiring a signature without prior arrangement with Crux. Procedural 1) Briefly explain the difference between heraldic titles of rank and heraldic office titles: 2) Who comprises the Lochac College of Heralds? 3) Who comprises the College of Arms? October 2010 Lochac PE Exam Page 1 of 12 4) What is an Order of Precedence (OP); who maintains this in Lochac? 5) What is a Letter of Intent (LoI); who issues this in Lochac? 6) What is a Letter of Acceptance and Return (LoAR); who issues this? 7) What is OSCAR? Briefly explain who may access different sections of it? 8) How many duplicate forms are necessary for a name & armory submission? To whom are they sent? 9) What documentation and how many copies of it must accompany a submission? 10) What, if any, action should a branch herald take on a submission before forwarding it? What may they NOT do? 11) Give two examples of errors that would result in an administrative return of a submission: October 2010 Lochac PE Exam Page 2 of 12 Voice Heraldry 12) How might you announce a tournament round including the following pairs of people? Include the introductory litany for one pair. -

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

Saint George Greek Orthodox Church Services Every Sunday

Saint George Greek Orthodox Church 70 West Street, PO Box 392 Keene, NH 03431-0392 The Rev. Dr. Theodore Stylianopoulos, Pastor Church: 352.6424 Home: 617.522.5768 College: 617.850.1238 Weekend: 835.6389 Email: [email protected] Website: www.stgeorgekeene.nh.goarch.org August 2010 Services Every Sunday In This Issue Father Ted’s Corner 2 Matins 9:00-10:00 a.m. Prayers and Saints 4 Diving Liturgy 10:00-11:30 a.m. Our Community 6 Daily Bible Readings 11 Worship Services in August August 1 Prosforo Bakers 10th Sunday of Matthew August 1: Maria Ioannou Procession of the Precious Cross August 15: Janet Harrison The Holy Seven Maccabees, Eleazar the August 29: Tiffany Mannion Martyr September 5: Vicky Balkanikos Matins: John 21:1-14 Epistle: St. Paul's First Letter to the Corinthians 4:9-16 Gospel: Matthew 17:14-23 Notable Feast Days in August August 8 August 6 11th Sunday of Matthew Transfiguration of Emilian the Confessor & Bishop of Cyzikos our Lord and Savior Our Holy Father Myronus the Wonderworker, Bishop of Crete Jesus Christ Matins: John 21:14-25 Epistle: St. Paul's First Letter to the Corinthians 9:2-12 August 9 Gospel: Matthew 18:23-35 St. Matthias the Apostle August 15 The Dormition of our Most Holy Lady the Theotokos and Ever August 16 Virgin Mary Translation of the Matins: Luke 1:39-49, 56 Image of Our Lord Epistle: St. Paul's Letter to the Philippians 2:5-11 and God and Savior, Gospel: Luke 10:38-42, 11:27-28 Jesus Christ August 22 Diomedes the 13th Sunday of Matthew Physician & Martyr of Agathonikos the Martyr of Nicomedea & his Companion Martyrs Tarsus Holy Martyr Anthuse Matins: Mark 16:1-8 August 20 St.