24. Principles of Wool Fabric Finishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Textile Printing

TECHNICAL BULLETIN 6399 Weston Parkway, Cary, North Carolina, 27513 • Telephone (919) 678-2220 ISP 1004 TEXTILE PRINTING This report is sponsored by the Importer Support Program and written to address the technical needs of product sourcers. © 2003 Cotton Incorporated. All rights reserved; America’s Cotton Producers and Importers. INTRODUCTION The desire of adding color and design to textile materials is almost as old as mankind. Early civilizations used color and design to distinguish themselves and to set themselves apart from others. Textile printing is the most important and versatile of the techniques used to add design, color, and specialty to textile fabrics. It can be thought of as the coloring technique that combines art, engineering, and dyeing technology to produce textile product images that had previously only existed in the imagination of the textile designer. Textile printing can realistically be considered localized dyeing. In ancient times, man sought these designs and images mainly for clothing or apparel, but in today’s marketplace, textile printing is important for upholstery, domestics (sheets, towels, draperies), floor coverings, and numerous other uses. The exact origin of textile printing is difficult to determine. However, a number of early civilizations developed various techniques for imparting color and design to textile garments. Batik is a modern art form for developing unique dyed patterns on textile fabrics very similar to textile printing. Batik is characterized by unique patterns and color combinations as well as the appearance of fracture lines due to the cracking of the wax during the dyeing process. Batik is derived from the Japanese term, “Ambatik,” which means “dabbing,” “writing,” or “drawing.” In Egypt, records from 23-79 AD describe a hot wax technique similar to batik. -

Fulled Wool Scarves Multiple Projects on the Same Threading

Fulled Wool Scarves multiple projects on the same threading MADELYN VAN DER HOOGT Choose from a fabulous array of colors and make lots of scarves for quick and easy holiday gifts. Change weft colors for different looks on the same warp—or change the colors of the warp, too! Simply tie a new warp onto the one you’ve just finished. The setts of both the warp and the weft in this project are very open to allow maximum fulling to take place during wet finishing. The result is a wonderfully soft, thick, cuddly, warm winter scarf. hese two scarves were woven on dif- secure them in front of the reed. ferent warps, both of Harrisville Then, taking the first end of the old T Shetland, one in Garnet, the other warp and the first end of the new warp on in Peacock. Both yarns are somewhat one side (right side if you are right hand- “heathered” (flecks of other colors are spun ed, left side if you are left-handed), tie into the yarn), a quality that makes them them together in an overhand knot. Re- work well with a variety of weft colors. peat with the next end from each warp and You can choose to weave many scarves on continue until all ends are tied. The knots one very long warp or even tie on new do not have to be exactly at the same point warps to change scarf colors completely. for every tie. Especially with wool, small Whatever you choose, you’ll find the tension differences between the threads weaving easy and fun. -

Barred Blanket Initialled CY and Dated 1726

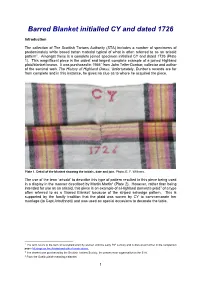

Barred Blanket initialled CY and dated 1726 Introduction The collection of The Scottish Tartans Authority (STA) includes a number of specimens of predominately white based tartan material typical of what is often referred to as an arisaid pattern1. Amongst these is a complete joined specimen initialled CY and dated 1726 (Plate 1). This magnificent piece is the oldest and largest complete example of a joined Highland plaid/blanket known. It was purchased in 19662 from John Telfer Dunbar, collector and author of the seminal work The History of Highland Dressi. Unfortunately, Dunbar’s records are far from complete and in this instance, he gives no clue as to where he acquired the piece. Plate 1. Detail of the blanket showing the initials, date and join. Photo: E. F. Williams. The use of the term ‘arisaid’ to describe this type of pattern resulted in this piece being used in a display in the manner described by Martin Martinii (Plate 2). However, rather than being intended for use as an arisaid, this piece is an example of a Highland domestic plaid3 of a type often referred to as a ‘Barred Blanket’ because of the striped selvedge pattern. This is supported by the family tradition that the plaid was woven by CY to commemorate her marriage (to Capt Arbuthnott) and was used on special occasions to decorate the table. 1 The term refers to the form of over-plaid worn by women until the early 18th century and is discussed further in the companion paper Musings on the Arisaid and other female dress. -

Fabricating Carbon Fiber Airframes, Part 2: Finishing

In This Issue Fabricating Carbon Fiber Airframes, Part 2: Finishing Cover Photo: Lift-off shot by Erin Card at NARAM56 in Pueblo, CO Apogee Components, Inc. — Your Source For Rocket Supplies That Will Take You To The “Peak-of-Flight” 3355 Fillmore Ridge Heights Colorado Springs, Colorado 80907-9024 USA www.ApogeeRockets.com e-mail: [email protected] Phone: 719-535-9335 Fax: 719-534-9050 ISSUE 371 AUGUST 12, 2014 Fabricating Carbon Fiber Airframes Part 2: Finishing By Alex Laraway Congratulations! You’ve moved onto what is frankly the most Start by releasing the lip of the mylar from around one side tedious part of fabricating tubing: getting it to look pretty. of the tube. Once you are finished, use a long dowel to be- One of the reasons carbon fiber is so highly valued is its aes- gin breaking the bond between the mylar and the epoxy on thetic characteristics. For this reason, bare carbon fiber is an the inside of the tube. Ram the dowel to the opposite end of attractive option for the finish on high-end sports cars, bikes, the tube and slowly work it around so that the entire mylar motorcycles and, of course, rockets. Getting a smooth gloss layer is broken out from the epoxy. After this step, the mylar “naked” carbon fiber is tiresome at best, especially starting should slide out with ease! with a peel ply texture. The basic idea is to give it a series of epoxy coats and sand each coat down with a different series of sandpaper grits with each epoxy pass. -

With Love & Blessings

SEPTEMBER 2013 ALL BUSINESS LIST DBA Name Address Line 1 Line 2 City State Zip Code "WITH LOVE & BLESSINGS" GIFTS-NOVELTIES 519 S PIN HIGH COURT PUEBLO WEST CO 81007 #1 A LIFESAFER OF COLORADO, INC 810 S PORTLAND AVE PUEBLO CO 81001 1 800 WATER DAMAGE 3100 GRANADA BLVD PUEBLO CO 81005 1 STORY LLC 16359 260TH ST GRUNDY CENTER IA 50638 10 TIGERS KUNG FU 121 BROADWAY AVE PUEBLO CO 81004 13TH STREET BARBER SHOP 1205 N ELIZABETH PUEBLO CO 81003 1-800 CONTACTS INC 66 E WARDSWORTH PARK DR DRAPER UT 84020 1A SMART START INC 4850 PLAZA DR IRVING TX 75063 1-DERFUL ROOFING & RESTORATION 9858 W GIRTON DR LAKEWOOD CO 80227 1ST ALERT SECURITY 301 N MAIN ST STE 304A PUEBLO CO 81003 1ST CONGREGATIONAL UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST 228 W EVANS PUEBLO CO 81004 1ST PRIORITY ROOFING 714 VENTURA ST SUITE B AURORA CO 80011 1ST RATE APPLIANCE 928 S SANTA FE AVE PUEBLO CO 81006 1ST RATE SERVICE PLUMBING 225 S SIESTA DR PUEBLO WEST CO 81007 21ST CENTURY BUILDERS 2401 W 11TH ST PUEBLO CO 81003 29TH ST. DETAIL 1803 W 29TH ST PUEBLO CO 81008 2ND STREET GARAGE EAST 1640 E 2ND ST PUEBLO CO 81001 3 MARGARITAS 3620 N FREEWAY PUEBLO CO 81008 3 T SYSTEMS 5990 GREENWOOD PLAZA BLVD, SU GREENWOOD VILLAGECO 80111 3308 INC 2275 DOWNEND ST COLORADO SPRINGS CO 80910 3BELOW 224 S UNION AVE PUEBLO CO 81003 3D SYSTEMS INC 333 THREE D SYSTEMS CIRCLE ROCKHILL SC 29730 3FORM INC 2300 SOUTH 2300 WEST STE B SALT LAKE CITY UT 84119 3M COMPANY 3M CENTER ST PAUL MN 55144 3SI SECURITY SYSTEMS INC 486 THOMAS JONES WAY STE 290 EXTON PA 19341 4 RIVERS EQUIPMENT LLC 685 E ENTERPRISE DR PUEBLO WEST -

EFFECTS of BIO-FINISHING on COTTON and COTTON/WOOL BLENDED FABRICS by SHRIDHAR CHIKODI, B.Tech. a THESIS in CLOTHING, TEXTILES

EFFECTS OF BIO-FINISHING ON COTTON AND COTTON/WOOL BLENDED FABRICS by SHRIDHAR CHIKODI, B.Tech. A THESIS IN CLOTHING, TEXTILES, AND MERCHANDISING Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved Accepted May, 1994 fjC fl£1-1 ;q;:; u goS TJ Jh ~t/'li I qq.lf /V/). I U>p·~ © 1994 Shridhar Chikodi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In accomplishing this work, there are many people who have inspired my determination. To begin with, I would like to thank my thesis committee chairman, Dr. Samina Khan, for her invaluable guidance and encouragement throughout this project. I am thankful to Dr. Shelley Harp for the consistent support and attention to detail which was invaluable. I extend my sincere thanks to Dr. R.D. Mehta whose research expertise has been crucial to the success of this project. I am also grateful to Dr. Jerry Mason, for his support throughout my stay at Tech. I am indebted to the personnel at International Center for Textile Research and Development and to Mark Grimson at Scanning Electron Microscopy lab, for their contribution to this research. I would like to express my heartfelt thanks to my parents, for their undying love, faith and immeasurable sacrifices they have made on my behalf. I truly owe them everything. A final acknowledgement I extend to my close friend Janie, for her never-ending encouragement, support, and assistance in the past two years. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS .. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . ll LIST OF TABLES . vi LIST OF FIGURES . viii CHAPTERS I . -

Education Teacher’S Kit

Industrial Heritage - The Textile Industry Education Teacher’s Kit Background There is archaeological evidence of textile production in Britain from the late-prehistoric period onwards. For many thousands of years wool was the staple textile product of Britain. The dominance of wool in the British textile industry changed rapidly during the eighteenth century with the development of mechanised silk production and then mechanised cotton production. By the mid-nineteenth century all four major branches of the textile industry (cotton, wool, flax, hemp and jute and silk) had been mechanised and the British landscape was dominated by over 10,000 mill buildings with their distinctive chimneys. Overseas competition led to a decline in the textile industry in the mid-twentieth century. Today woollen production is once again the dominant part of the sector together with artificial and man-made fibres, although output is much reduced from historic levels. Innovation Thomas Lombe’s silk mill, built in 1721, is regarded as the first factory-based textile mill in Britain. However, it was not until the handloom was developed following the introduction of John Kay’s flying shuttle in 1733 that other branches of the textile industry (notably cotton and wool) became increasingly mechanised. In the second half of the eighteenth century, a succession of major innovations including James Hargreaves’s spinning jenny (1764), Richard Arkwright’s water frame (1769), his carding engine (1775), and Samuel Crompton’s mule (1779), revolutionised the preparation and spinning of cotton and wool and led to the establishment of textile factories where several machines were housed under one roof. -

Recent Trends in Textile and Apparel Finishes

International Journal of Engineering Science Invention (IJESI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 6734, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 6726 www.ijesi.org ||Volume 8 Issue 08 Series. I || Aug 2019 || PP 59-63 Recent Trends in Textile and Apparel Finishes Ms.N.Gayathri 1 & Mrs.V.A.Rinsey Antony2 1. Assistant Professor, Dept. Of Costume Design and Fashion Sri Krishna Arts and Science College, Coimbatore (India) 2. Assistant Professor, Dept. Of Costume Design and Fashion Sri Krishna Arts and Science College, Coimbatore (India) Corresponding Author: Ms.N.Gayathri Abstract: The Indian textile industry is as diverse as the country is and as complex an entity. There is an organised, decentralised sector and down the line, there are weavers, artisans as well as the farmers. Emerging technologies will always be the best available technologies keeping energy saving in mind as policy makers and regulators are addressing environmental issues in industries with the application of abatement strategy. This will improve the environmental performance of the industries and also limits pollutant discharges and helps the environment. Textile producers can sustain their competitiveness in a liberalised and competition-driven market only when they are able to develop new markets and enhance productivity by raising their real end product and investing in emerging technology. Added value can be obtained only by shifting away from labour-intensive mass products and concentrating on new, high-quality specialised products. Key words: environment Finishing, innovation, technology, textile. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 05-08-2019 Date of acceptance: 20-08-2019 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- I. INTRODUCTION: A textile is any kind of woven, knitted, knotted (as in macramé) or tufted cloth, or a non- woven fabric (a cloth made of fibers that have been bonded into a fabric, e.g. -

Sewing with Fleece.Pub

WELCOME Welcome to the Sewing With Fleece Project! Please read through this guide carefully, as it contains information and suggestions that are important for your project. 4-H Leaders can obtain a Leader Project Guide and further resources from the PEI 4-H Office. Hopefully you, as a member, will “Learn To Do By Doing” through hands-on activities that will encourage learning and enjoyment. If you have any questions, contact your District 4-H Officer or your 4-H project leader. 4-H YEAR COMPLETION You must complete You complete a project by: all of the listed • completing the project Achievement Day requirements aspects in order to • completing a communication project show at Fairs and • completing a community project Exhibitions. • completing an agriculture awareness project • taking part in Achievement Day ACHIEVEMENT DAY REQUIREMENTS - LEVEL 1 Three (3) Samples 15 Small Pillow 10 One Pair of Mittens* 45 A Hat* 30 100 Marks • Patterns for the mittens and hat are included in the Leaders’ Project Manual • Members are encouraged to make a flower pin - this item is optional EXHIBITION REQUIREMENT - LEVEL I Pair of Mittens and Hat ACHIEVEMENT DAY REQUIREMENTS - LEVEL II Three (3) Samples 20 Stuffed Animal Pillow 80 (minimum of 50 cm (20”) in length) 100 Marks EXHIBITION REQUIREMENT - LEVEL II Stuffed Animal Pillow SEWING WITH FLEECE Ages for 4-H members as of January 1st of the 4-H year: Junior: 9-11 years Check out the PEI 4-H Web Site Intermediate: 12-14 years May 2013 Senior: 15-21 years www.pei4h.pe.ca HELPFUL RESOURCES! BE A GOOD SPORT! www.sewing.about.com In the spirit of learn to do by doing, all www.simplicity.com those involved in 4-H are encouraged to www.craftsitedirectory.com/sewing practice good sportsmanship, use www.sewing.lifetips.com common sense at all 4-H activities, and www.kwiksew.com the work in any 4-H project should be www.sewnews.com the member’s own work. -

October, 2012 All Business List DBA Name Address Line 1 Line 2 City

October, 2012 All Business List DBA Name Address Line 1 Line 2 City State Zip Code "THE RIGHT HAND" HANDYMAN SERVICES 945 29TH LANE PUEBLO CO 81006 1 800 WATER DAMAGE 3100 GRANADA BLVD PUEBLO CO 81005 1 STORY LLC 16359 260TH ST GRUNDY CENTER IA 50638 1-800 CONTACTS INC 66 E WARDSWORTH PARK DR DRAPER UT 84020 10TH STREET CAFE 215 W 10TH ST PUEBLO CO 81003 13TH STREET BARBER SHOP 1205 N ELIZABETH PUEBLO CO 81003 1A SMART START INC 4850 PLAZA DR IRVING TX 75063 1ST ALERT SECURITY 301 N MAIN ST STE 304A PUEBLO CO 81003 1ST CHOICE PROPERTY MAINTENANCE 1725 HARLOW AVE PUEBLO CO 81006 1ST PLACE FOR MEMORIES LLC 1643 NORTH GILL DR PUEBLO WEST CO 81007 1ST PRIORITY ROOFING 714 VENTURA ST SUITE B AURORA CO 80011 1ST RATE APPLIANCE 928 S SANTA FE AVE PUEBLO CO 81006 1ST RATE SERVICE PLUMBING 225 S SIESTA DR PUEBLO WEST CO 81007 1ST STOP - 3103 623 GRAND PUEBLO CO 81003 1ST STOP - 3104 725 W NORTHERN PUEBLO CO 81004 1ST STOP - 3106 2801 N ELIZABETH PUEBLO CO 81008 1ST STOP - 3107 1350 E 4TH PUEBLO CO 81001 1ST STOP - 3109 2102 NORWOOD PUEBLO CO 81003 1ST STOP - 3113 723 PUEBLO BLVD PUEBLO CO 81005 21ST CENTURY BUILDERS 2401 W 11TH ST PUEBLO CO 81003 29TH ST AUTO DETAIL 1803 W 29TH ST PUEBLO CO 81008 2ND STREET GARAGE EAST 1640 E 2ND ST PUEBLO CO 81001 3 MARGARITAS 3620 N FREEWAY PUEBLO CO 81008 3 T SYSTEMS 5990 GREENWOOD PLAZA BLVD, SUITE 350 GREENWOOD VILLAGE CO 80111 3BELOW 224 S UNION AVE PUEBLO CO 81003 3D SYSTEMS INC 333 THREE D SYSTEMS CIRCLE ROCKHILL SC 29730 3FORM INC 2300 SOUTH 2300 WEST STE B SALT LAKE CITY UT 84119 3M COMPANY 3M CENTER -

Digital Textile Printing Opportunities for Sign Companies

Digital Textile Printing Opportunities for Sign Companies This survey remains the property of the International Sign Association. None of the information contained within can be republished without permission from ISA. PREPARED BY: InfoTrends ISA Whitepaper Digital Textile Printing Opportunities for Sign Companies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................................................................2 Key Highlights ..................................................................................................................................2 Recommendations ...........................................................................................................................2 Soft Signage Applications ...............................................................................................................3 The 2014 Textile Industry ................................................................................................................4 Market Growth in Wide Format Digital Printing ...............................................................................5 Technological Shifts ....................................................................................................................5 Application Trends .......................................................................................................................7 Vendors of Graphic Textile and Decorative Solutions .....................................................................7 -

Notes on Fulling and Fulling Mills

Notes on Fulling and Fulling Mills When cloth comes from the loom, it is an open weave, and also greasy since the yarn needs to be lubricated for easy weaving. Fulling both removes the grease so that the cloth will later take dye, and felts it, with the fibres tangling together to form a full cloth that is continuous in two dimensions and no longer shows the pattern of the weaving. The process requires the cloth to be beaten while immersed in a mixture of water with fuller’s earth (a kind of clay), urine, and certain soapy plant extracts. Small articles like hosiery or caps could be beaten by hand or with a club, but lengths of cloth were normally ‘walked’, trodden underfoot in shallow troughs. (The French term fouler still has the secondary meaning of ‘to trample underfoot’). This was a very long, labour intensive, business, which may have had to be repeated several times. Mechanisation therefore came early. Isolated mentions in France date to the later eleventh century, but the earliest known examples in England are a hundred years later. By about 1200, documents have to distinguish fulling from corn mills, indicating that both sorts were in existence. Many fulling mills were in ecclesiastical estates. By the early thirteenth century, the bishops of Winchester possessed two such mills at Witney, among other places, and the nunnery at Godstow was partly supported by tithes from fulling mills. By the middle of the century, manual fulling seems to have been obsolete except for cloths of the very highest quality - which also would have used yarn spun with a spindle whorl, not on the wheel.