NIOSH Skin Notation Profiles Formaldehyde/Formalin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formaldehyde Test Kit Utility

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Cutan Ocul Manuscript Author Toxicol. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019 June 01. Published in final edited form as: Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2019 June ; 38(2): 112–117. doi:10.1080/15569527.2018.1471485. Undeclared Formaldehyde Levels in Patient Consumer Products: Formaldehyde Test Kit Utility Jason E. Ham1, Paul Siegel1,*, and Howard Maibach2 1Health Effects Laboratory Division, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Morgantown, WV, USA 2Department of Dermatology, School of Medicine, University of California-San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA Abstract Formaldehyde allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) may be due to products with free formaldehyde or formaldehyde-releasing agents, however, assessment of formaldehyde levels in such products is infrequently conducted. The present study quantifies total releasable formaldehyde from “in-use” products associated with formaldehyde ACD and tests the utility of commercially available formaldehyde spot test kits. Personal care products from 2 patients with ACD to formaldehyde were initially screened at the clinic for formaldehyde using a formaldehyde spot test kit. Formaldehyde positive products were sent to the laboratory for confirmation by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. In addition, 4 formaldehyde spot test kits were evaluated for potential utility in a clinical setting. Nine of the 10 formaldehyde spot test kit positive products obtained from formaldehyde allergic patients had formaldehyde with total releasable formaldehyde levels ranging from 5.4 to 269.4 μg/g. Of these, only 2 shampoos tested listed a formaldehyde-releasing agent in the ingredients or product literature. Subsequently, commercially available formaldehyde spot test kits were evaluated in the laboratory for ability to identify formaldehyde in personal care products. -

Formaldehyde May Be Found in Cosmetic Products Even When Unlabelled

Open Med. 2015; 10: 323-328 Research Article Open Access Laura Malinauskiene*, Audra Blaziene, Anzelika Chomiciene, Marléne Isaksson Formaldehyde may be found in cosmetic products even when unlabelled Abstract: Concomitant contact allergy to formaldehyde reliable method for detecting formaldehyde presence in and formaldehyde-releasers remains common among cosmetic products. patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Concentration of free formaldehyde in cosmetic products within allowed Keywords: chromotropic acid; formaldehyde; formalde- limits have been shown to induce dermatitis from short- hyde-releaser; high-performance liquid chromatography term use on normal skin. DOI 10.1515/med-2015-0047 The aim of this study was to investigate the formalde- Received: February 2, 2015; accepted: May 28, 2015 hyde content of cosmetic products made in Lithuania. 42 samples were analysed with the chromotropic acid (CA) method for semi-quantitative formaldehyde deter- mination. These included 24 leave-on (e.g., creams, 1 Introduction lotions) and 18 rinse-off (e.g., shampoos, soaps) products. Formaldehyde is a well-documented contact allergen. Formaldehyde releasers were declared on the labels of 10 Over recent decades, the prevalence of contact allergy to products. No formaldehyde releaser was declared on the formaldehyde has been found to be 8-9% in the USA and label of the only face cream investigated, but levels of free 2-3% in European countries [1]. formaldehyde with the CA method was >40 mg/ml and Formaldehyde as such is very seldomly used in cosmetic when analysed with a high-performance liquid chromato- products anymore, but preservatives releasing formalde- graphic method – 532 ppm. According to the EU Cosmetic hyde in the presence of water are widely used in many directive, if the concentration of formaldehyde is above cosmetic products (e.g., shampoos, creams, etc.), topical 0.05% a cosmetic product must be labelled “contains medications and household products (e.g., dishwashing formaldehyde“. -

Allergic Contact Dermatitis from Formaldehyde Exposure

DOI: 10.5272/jimab.2012184.255 Journal of IMAB - Annual Proceeding (Scientific Papers) 2012, vol. 18, book 4 ALLERGIC CONTACT DERMATITIS FROM FORMALDEHYDE EXPOSURE Maya Lyapina1, Angelina Kisselova-Yaneva 2, Assya Krasteva2, Mariana Tzekova -Yaneva2, Maria Dencheva-Garova2 1) Department of Hygiene, Medical Ecology and Nutrition, Medical Faculty, 2) Department of Oral and Image Diagnostic, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Medical University, Sofia,Bulgaria ABSTRACT atmospheric air, tobacco smoke, use of cosmetic products Formaldehyde is a ubiquitous chemical agent, a part and detergents, and in less extend – water and food of our outdoor and indoor working and residential consumption (11, 81). It is released into the atmosphere environment. Healthcare workers in difficult occupations are through fumes from automobile exhausts without catalytic among the most affected by formaldehyde exposure. convertors and by manufacturing facilities that burn fossil Formaldehyde is an ingredient of some dental materials. fuels in usual concentration about 1-10 ppb. Uncontrolled Formaldehyde is well-known mucous membrane irritant and forest fires and the open burning of waste also give off a primary skin sensitizing agent associated with both contact formaldehyde. It is believed that the daily exposure from dermatitis (Type IV allergy), and immediate, anaphylactic atmospheric air is up to 0.1 mg (35, 43, 44). reactions (Type I allergy). Inhalation exposure to According to the WHO industrial emissions could formaldehyde was identified as a potential cause of asthma. appear at each step of production, use, transportation, or Quite a few investigations are available concerning health deposition of formaldehyde-containing products. issues for dental students following formaldehyde exposure. Formaldehyde emissions are detected from various Such studies would be beneficial for early diagnosis of industries – energy industry, wood and paper product hypersensitivity, adequate prophylactic, risk assessment and industries, textile production and finishing, chemical management of their work. -

Nomination Background: N-(3-Chloroallyl)Hexaminium Chloride

• NATIONAL TOXICOLOGY PROGRAM EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF SAFETY AND TOXICITY INFORMATION N-(3-CHLOROALLYL)HEXAMINIUM CHLORIDE CAS Number 4080-31-3 July 16, 1991 Submitted to: NATIONAL TOXICOLOGY PROGRAM Submitted by: Arthur D. Little, Inc. Chemical Evaluation Committee Draft Report • • TABLE OF CONTENTS Page L NOMINATION HISTORY AND REVIEW .................... 1 II. CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL DATA ....................... 3 III. PRODUCTION/USE ................................... 5 IV. EXPOSURE/REGULATORY STATUS...................... .10 V. TOXICOLOGICAL EFFECTS ........................... .11 VI. STRUCTURE ACTIVITY RELATIONSHIPS ..................48 VII. REFERENCES ..................................... : . ......... 49 APPENDIX I, ON-LINE DATA BASES SEARCHED ............ .53 APPENDIX II, SAFETY INFORMATION.................... .54 1 ,, .• • • OVERVJEWl Nomination History: N-(3-Chloroallyl)hexaminium chloride was originally nominated for carcinogenicity testing by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in 1980 with moderate priority. In March 1980, the Chemical Evaluation Committee (CEC) recommended carcinogenicity testing. Due to budgetary cutbacks in 1982, this compound was reevaluated and recommended for in vitro cytogenetics and chemical disposition testing by the CEC, and was selected for chemical disposition testing by the Executive Committee. The renomination of this chemical in 1984 by the NCI was based on potentialfor significant human exposure and concern that it may be carcinogenic due to structural considerations. This recent nomination was -

Safety Assessment of Imidazolidinyl Urea As Used in Cosmetics

Safety Assessment of Imidazolidinyl Urea as Used in Cosmetics Status: Re-Review for Panel Review Release Date: May 10, 2019 Panel Meeting Date: June 6-7, 2019 The 2019 Cosmetic Ingredient Review Expert Panel members are: Chair, Wilma F. Bergfeld, M.D., F.A.C.P.; Donald V. Belsito, M.D.; Ronald A. Hill, Ph.D.; Curtis D. Klaassen, Ph.D.; Daniel C. Liebler, Ph.D.; James G. Marks, Jr., M.D., Ronald C. Shank, Ph.D.; Thomas J. Slaga, Ph.D.; and Paul W. Snyder, D.V.M., Ph.D. The CIR Executive Director is Bart Heldreth, Ph.D. This safety assessment was prepared by Christina L. Burnett, Senior Scientific Analyst/Writer. © Cosmetic Ingredient Review 1620 L Street, NW, Suite 1200 ♢ Washington, DC 20036-4702 ♢ ph 202.331.0651 ♢ fax 202.331.0088 ♢ [email protected] Distributed for Comment Only -- Do Not Cite or Quote Commitment & Credibility since 1976 Memorandum To: CIR Expert Panel Members and Liaisons From: Christina Burnett, Senior Scientific Writer/Analyst Date: May 10, 2019 Subject: Re-Review of the Safety Assessment of Imidazolidinyl Urea Imidazolidinyl Urea was one of the first ingredients reviewed by the CIR Expert Panel, and the final safety assessment was published in 1980 with the conclusion “safe when incorporated in cosmetic products in amounts similar to those presently marketed” (imurea062019origrep). In 2001, after considering new studies and updated use data, the Panel determined to not re-open the safety assessment (imurea062019RR1sum). The minutes from the Panel deliberations of that re-review are included (imurea062019min_RR1). Minutes from the deliberations of the original review are unavailable. -

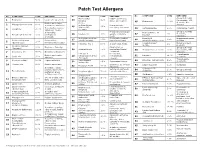

Patch Test Allergens

Patch Test Allergens No. COMPOUND CONC EXPOSURE No. COMPOUND CONC EXPOSURE No. COMPOUND CONC EXPOSURE Mixed dialkyl Rubber accelerator, Group B steroids: 1 Benzocaine 5.0% Local ester anesthetic 24 1.0% fluocinonide, TAC, thiourea assoc. w/ neoprene. 45 Budesonide 0.01% desonide. Also Rubber accelerator, Cl+Me- 2 Mercaptobenzothiazole 1.0% isothiazolinone Preservative in Group D. cutting oils, antifreeze 25 .01% In cosmetics, waxes, (Kathon CG, cosmetics, shampoos. Compositae mix 5.0% Compositae flowers. 3 Colophony 20.0% 46 adhesives. “Rosin.” 100ppm) Group D steroids: In hair dyes, Preservative in topical Hydrocortisone-17- 47 1% Temovate, 4 Paraphenylenediamine 1.0% photographic 26 Paraben mix 12% agents, cosmetics, butyrate Diprosone. chemicals foods. Methyldibromoglutar Preservative against Dimethylol In permanent press 27 0.5% 48 4.5% Imidazolidinyl urea Preservative, onitrile (MDBGN) bacteria and fungi dihydroxyethylene urea clothing. 5 2.0% (Germall 115) formaldehyde releaser Cocamidopropyl In hair and bath 28 Fragrance mix 1 8.0% In cosmetics, foods. 1% 49 ibetaine products. Cinnamic aldehyde 6 1.0% Fragrance. flavoring Disinfectant on (Cinnamyl) Group B steroids: 29 Glutaraldehyde 0.5% medical and dental 50 Triamcinolone acetonide 1.0% fluocinonide, TAC, 7 Amerchol L 101 50.0% Emulsifiers, Emollients equipment desonide. 2-Bromo-2- Preservative, Topical amide Rubber accelerator, 51 Lidocaine 15.0% 8 Carba mix 3.0% 30 nitropropane-l,3-diol 0.5% formaldehyde anesthetic. Adhesive (Bronopol) releaser. Topical amide Neomycin sulfate 20.0% Topical antibiotic. Sesquiterpene 52 Dibucaine hydrochloride 2.5% 9 0.1% Compositae flowers. anesthetic. 31 lactone Mix 10 Thiuram mix 1.0% Rubber accelerator Cosmetics, scents and Lauryl glucoside 3.0% surfactant Fragrance Mix II 14.0% 53 32 flavorings In leather, rubber, Clobetasol-17- plastics, disinfectants, Vehicle for cosmetics, 54 1.0% Group B steroids Formaldehyde 1.0% propionate 11 permanent press 33 Propylene glycol 30.0% topical medications. -

Relationship Between Formaldehyde and Quaternium15 Contact

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Relationship between formaldehyde and quaternium-15 contact allergy. Influence of strength of patch test reactions de Groot, Anton C.; Blok, Janine; Coenraads, Pieter-Jan Published in: CONTACT DERMATITIS IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2010 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): de Groot, A. C., Blok, J., & Coenraads, P-J. (2010). Relationship between formaldehyde and quaternium-15 contact allergy. Influence of strength of patch test reactions. CONTACT DERMATITIS, 63(4), 187-191. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 Contact Dermatitis 2010: 63: 187–191 © 2010 John Wiley & Sons A/S Printed in Singapore. -

Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety on Quaternium-15

SCCS/1344/10 Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety SCCS OPINION ON Quaternium-15 (cis-isomer) COLIPA n° P63 The SCCS adopted this opinion at its 13th plenary meeting of 13-14 December 2011 SCCS/1344/10 Opinion on quaternium-15 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ About the Scientific Committees Three independent non-food Scientific Committees provide the Commission with the scientific advice it needs when preparing policy and proposals relating to consumer safety, public health and the environment. The Committees also draw the Commission's attention to the new or emerging problems which may pose an actual or potential threat. They are: the Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS), the Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks (SCHER) and the Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR) and are made up of external experts. In addition, the Commission relies upon the work of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the European Centre for Disease prevention and Control (ECDC) and the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). SCCS The Committee shall provide opinions on questions concerning all types of health and safety risks (notably chemical, biological, mechanical and other physical risks) of non-food consumer products (for example: cosmetic products and their ingredients, toys, textiles, clothing, personal care and household products such as detergents, etc.) and services (for example: tattooing, artificial sun tanning, etc.). Scientific Committee members Jürgen Angerer, Ulrike Bernauer, Claire Chambers, Qasim Chaudhry, Gisela Degen, Elsa Nielsen, Thomas Platzek, Suresh Chandra Rastogi, Vera Rogiers, Christophe Rousselle, Tore Sanner, Jan van Benthem, Jacqueline van Engelen, Maria Pilar Vinardell, Rosemary Waring, Ian R. -

Formaldehyde and Formaldehyde Releasers

INVESTIGATION REPORT FORMALDEHYDE AND FORMALDEHYDE RELEASERS SUBSTANCE NAME: Formaldehyde IUPAC NAME: Methanal EC NUMBER: 200-001-8 CAS NUMBER: 50-00-0 SUBSTANCE NAME(S): - IUPAC NAME(S): - EC NUMBER(S): - CAS NUMBER(S):- CONTACT DETAILS OF THE DOSSIER SUBMITTER: EUROPEAN CHEMICALS AGENCY Annankatu 18, P.O. Box 400, 00121 Helsinki, Finland tel: +358-9-686180 www.echa.europa DATE: 15 March 2017 CONTENTS INVESTIGATION REPORT – FORMALDEHYDE AND FORMALDEHYDE RELEASERS ................ 1 1. Summary.............................................................................................................. 1 2. Report .................................................................................................................. 2 2.1. Background ........................................................................................................ 2 3. Approach .............................................................................................................. 4 3.1. Task 1: Co-operation with FR and NL ..................................................................... 4 3.2. Task 2: Formaldehyde releasers ........................................................................... 4 4. Results of investigation ........................................................................................... 6 4.1. Formaldehyde..................................................................................................... 6 4.2. Information on formaldehyde releasing substances and their uses ............................ 6 4.2.1. -

Imidazolidinyl Urea

Imidazolidinyl urea 39236-46-9 OVERVIEW This material was prepared for the National Cancer Institute (NCI) for consideration by the Chemical Selection Working Group (CSWG) by Technical Resources International, Inc. under contract no. N02-07007. Imidazolidinyl urea came to the attention of the NCI Division of Cancer Biology (DCB) as the result of a class study on formaldehyde releasers. Used in combination with parabens, imidazolidinyl urea is one of the most widely used preservative systems in the world and is commonly found in cosmetics. Based on a lack of information in the available literature on the carcinogenicity and genetic toxicology, DCB forwarded imidazolidinyl urea to the NCI Short-Term Toxicity Program (STTP) for mutagenicity testing. Based on the results from the STTP, further toxicity testing of imidazolidinyl urea may be warranted. INPUT FROM GOVERNMENT AGENCIES/INDUSTRY Dr. John Walker, Executive Director of the TSCA Interagency Testing Committee (ITC), provided information on the production volumes for this chemical. Dr. Harold Seifried of the NCI provided mutagenicity data from the STTP. NOMINATION OF IMIDAZOLIDINYL UREA TO THE NTP Based on a review of available relevant literature and the recommendations of the Chemical Selection Working Group (CSWG) held on December 17, 2003, NCI nominates this chemical for testing by the National Toxicology Program (NTP) and forwards the following information: • The attached Summary of Data for Chemical Selection • Copies of references cited in the Summary of Data for Chemical Selection • CSWG recommendations to: (1) Evaluate the chemical for genetic toxicology in greater depth than the existing data, (2) Evaluate the disposition of the chemical in rodents, specifically for dermal absorption, (3) Expand the review of the information to include an evaluation of possible break- down products, especially diazolidinyl urea and formaldehyde. -

Survey and Health Assessment of Preservatives in Toys

Survey and health assessment of preservatives in toys Corrected version Survey of chemical substances in consum- er products No. 124 October 2016 Publisher: The Danish Environmental Protection Agency Editor: Pia Brunn Poulsen, FORCE Technology Rasmus Nielsen, FORCE Technology ISBN: 978-87-93529-22-9 Corrections of “Survey of chemical substances in consumer products no. 124”, 2014 are to be found on page 45. See footnote no. 10. Corrections of “Survey of chemical substances in consumer products no. 124”, 2016 are made on page 47, where this text is deleted: BIT is a so-called formaldehyde releaser, which means that the substance can release formaldehyde. Formaldehyde is classified as carcinogenic in category 2 and is allergenic. When the occasion arises, the Danish Environmental Protection Agency will publish reports and papers concerning research and development projects within the environmental sector, financed by study grants provided by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency. It should be noted that such publications do not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the Danish Environmental Protection Agency. However, publication does indicate that, in the opinion of the Danish Environmental Protection Agency, the content represents an important contribution to the debate surrounding Danish environmental policy. Sources must be acknowledged. Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................. 6 Conclusion and Summary ......................................................................................... -

Preservatives

Preservatives David C. Steinberg, FRAPS Steinberg & Associates, Inc. September 19, 2017 Who Cares About Preservatives? • They are all toxic • They are all dangerous pesticides • They are associated with every disease known to mankind • They are chemicals • They are unnatural • They add costs with no benefit • Hey, I can sell more of my product calling it “preservative free”. Because of This Mentality We Are Losing All of Our Preservatives • Marketing and NGO’s will never be satisfied. • All the preservatives used in cosmetics have long history of safe use. • Complaints about cosmetic injuries and more specifically, preservatives are very few. – Although the real facts are unknown • We are now seeing a significant increase in recalls due to microbial contamination Definition Preservation is the prevention or retardation of product deterioration from the time of manufacture until the product is used up by the consumer. This deterioration is due to microorganisms. Diseases can be spread by contaminated cosmetics Microbial contamination is adulteration as defined by the FDA What is a Preservative? • Chemical agents added to products to prevent the growth and to destroy microorganisms. • We add these to “clean” products to prevent deterioration by consumers under normal and foreseeable use conditions. • We establish the adequacy of preservation by running an appropriate preservative efficacy or challenge test (PET). Challenge Testing (PET) • A short term in vitro test to see if our product is adequately preserved. • Works well for “typical” products but not for “atypical” cosmetics. – Typical cosmetics have water as the continuous phase or are aqueous solutions. – Atypical cosmetics have low water content or are anhydrous or do not have water as the external phase of an emulsion.