Chapter 3. GEOLOGIC EFFECTS and RECORDS of TSUNAMIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind-Caused Waves Misleads Us Energy Is Transferred to the Wave

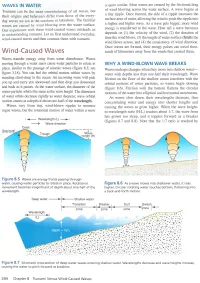

WAVES IN WATER is quite similar. Most waves are created by the frictional drag of wind blowing across the water surface. A wave begins as Tsunami can be the most overwhelming of all waves, but a tiny ripple. Once formed, the side of a ripple increases the their origins and behaviors differ from those of the every day waves we see at the seashore or lakeshore. The familiar surface area of water, allowing the wind to push the ripple into waves are caused by wind blowing over the water surface. a higher and higher wave. As a wave gets bigger, more wind Our experience with these wind-caused waves misleads us energy is transferred to the wave. How tall a wave becomes in understanding tsunami. Let us first understand everyday, depends on (1) the velocity of the wind, (2) the duration of wind-caused waves and then contrast them with tsunami. time the wind blows, (3) the length of water surface (fetch) the wind blows across, and (4) the consistency of wind direction. Once waves are formed, their energy pulses can travel thou Wind-Caused Waves sands of kilometers away from the winds that created them. Waves transfer energy away from some disturbance. Waves moving through a water mass cause water particles to rotate in WHY A WIND-BLOWN WAVE BREAKS place, similar to the passage of seismic waves (figure 8.5; see Waves undergo changes when they move into shallow water figure 3.18). You can feel the orbital motion within waves by water with depths less than one-half their wavelength. -

Tsunami, Seiches, and Tides Key Ideas Seiches

Tsunami, Seiches, And Tides Key Ideas l The wavelengths of tsunami, seiches and tides are so great that they always behave as shallow-water waves. l Because wave speed is proportional to wavelength, these waves move rapidly through the water. l A seiche is a pendulum-like rocking of water in a basin. l Tsunami are caused by displacement of water by forces that cause earthquakes, by landslides, by eruptions or by asteroid impacts. l Tides are caused by the gravitational attraction of the sun and the moon, by inertia, and by basin resonance. 1 Seiches What are the characteristics of a seiche? Water rocking back and forth at a specific resonant frequency in a confined area is a seiche. Seiches are also called standing waves. The node is the position in a standing wave where water moves sideways, but does not rise or fall. 2 1 Seiches A seiche in Lake Geneva. The blue line represents the hypothetical whole wave of which the seiche is a part. 3 Tsunami and Seismic Sea Waves Tsunami are long-wavelength, shallow-water, progressive waves caused by the rapid displacement of ocean water. Tsunami generated by the vertical movement of earth along faults are seismic sea waves. What else can generate tsunami? llandslides licebergs falling from glaciers lvolcanic eruptions lother direct displacements of the water surface 4 2 Tsunami and Seismic Sea Waves A tsunami, which occurred in 1946, was generated by a rupture along a submerged fault. The tsunami traveled at speeds of 212 meters per second. 5 Tsunami Speed How can the speed of a tsunami be calculated? Remember, because tsunami have extremely long wavelengths, they always behave as shallow water waves. -

Tsunamis in Alaska

Tsunami What is a Tsunami? A tsunami is a series of traveling waves in water that are generated by violent vertical displacement of the water surface. Tsunamis travel up to 500 mph across deep water away from their generation zone. Over the deep ocean, there may be very little displacement of the water surface; but since the wave encompasses the depth of the water column, wave amplitude will increase dramatically as it encounters shallow coastal waters. In many cases, a El Niño tsunami wave appears like an endlessly onrushing tide which forces its way around through any obstacle. The image on the left illustrates how the amplitude of a tsunami wave increases as it moves from the deep ocean water to the shallow coast. Over deep water, the wave length is long, and the wave velocity is very fast. By the time the wave reaches the coast, wave length decreases quickly and wave speed slows dramatically. As this takes place, wave height builds up as it prepares to inundate the shore. Why do Tsunamis occur in Alaska? Subduction-zone mega-thrust earthquakes, the most powerful earthquakes in the world, can produce tsunamis through fault boundary rupture, deformation of an overlying plate, and landslides induced by the earthquake (IRIS, 2016). Megathrust earthquakes occur along subduction zones, such as those found along the ring of fire (see image to the right). The ring of fire extends northward along the coast of western North America, then arcs westward along the southern side of the Aleutians, before curving southwest along the coast of Asia. -

2018 NOAA Science Report National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S

2018 NOAA Science Report National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Technical Memorandum NOAA Research Council-001 2018 NOAA Science Report Harry Cikanek, Ned Cyr, Ming Ji, Gary Matlock, Steve Thur NOAA Silver Spring, Maryland February 2019 NATIONAL OCEANIC AND NOAA Research Council noaa ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION 2018 NOAA Science Report Harry Cikanek, Ned Cyr, Ming Ji, Gary Matlock, Steve Thur NOAA Silver Spring, Maryland February 2019 UNITED STATES NATIONAL OCEANIC National Oceanic and DEPARTMENT OF AND ATMOSPHERIC Atmospheric Administration COMMERCE ADMINISTRATION Research Council Wilbur Ross RDML Tim Gallaudet, Ph.D., Craig N. McLean Secretary USN Ret., Acting NOAA NOAA Research Council Chair Administrator Francisco Werner, Ph.D. NOAA Research Council Vice Chair NOTICE This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency or Contractor thereof. Neither the United States Government, nor Contractor, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Mention of a commercial company or product does not constitute an endorsement by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. -

The Kingdom of Tonga Devastated by a Megatsunami in the Mid-15Th Century

EGU21-5317, updated on 25 Sep 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-5317 EGU General Assembly 2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. The kingdom of Tonga devastated by a megatsunami in the mid-15th century Franck Lavigne1,2,3, Julie Morin4, Wassmer Patrick2, Weller Olivier5, Kula Taaniela6, Ana V. Maea6, Karim Kelfoun7, Fatima Mokadem2, Raphael Paris7, Mukhamad N. Malawani1,2,8, Faral Audrey1,2, Mhammed Benbakkar7, Ségolène Saulnier-Copard2, Céline M. Vidal4, Tu’I’ahai Tu’I’afitu6, Gomez Christopher9, and Fuka Kitekei’aho10 1Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne University, ([email protected]) 2Laboratory of Physical Geography, UMR 8591 CNRS, Meudon, France 3Institut Universitaire de France, Paris, France 4Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 5Trajectoires, UMR 8215 CNRS, Paris, France 6Ministry of Land and Natural Resources, Natural Resources Division, Nuku'alofa, Kingdom of Tonga 7Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans, Université Clermont Auvergne, CNRS, IRD, OPGC, France 8Faculty of Geography, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 9Laboratory of Sediment Hazards and Disaster Risk, Kobe University, Japan 10Geocare & Petroleum Consult Ltd, Nuku'alofa, Kingdom of Tonga The pre-colonial history of Tonga and West Polynesia still suffers from major gaps because its reconstruction is essentially based on legends left by oral tradition, and by archaeological evidence somehow difficult to interpret. By the fourteenth century, the powerful Tu'i Tonga kingdom united the islands of the Tongan archipelago under a centralised authority and, according to tradition, extended its influence to neighbouring island groups in the Central Pacific. However, some periods of deep crisis were identified, e.g. -

Literature Review of Tsunami Sources Affecting Tsunami Hazard Along the US East Coast

Literature review of tsunami sources affecting tsunami hazard along the US East Coast Department of Ocean Engineering, University of Rhode Island Narragansett, USA Feb. 21, 2011 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND ...................................................................................................................... 3 2. LITERATURE REVIEW OF RELEVANT TSUNAMI SOURCES .................................... 5 2.1 Submarine Mass Failures ........................................................................................................ 5 2.2 Co-seismic tsunamis .................................................................................................................. 8 2.2.1 Review of literature on Caribbean subduction zone ............................................................. 8 2.2.2 NOAA Forecast Source Database for Caribbean subduction zone ............................... 16 2.2.3 Azores-Gibraltar convergence zone .......................................................................................... 17 2.3 Cumbre Vieja Volcano flanK collapse ............................................................................... 21 3. INITIAL SOURCE DEFINITIONS AND TSUNAMI SIMULATIONS .......................... 24 3.1 Modeling methodology .......................................................................................................... 24 3.1.1 Initial conditions for model .......................................................................................................... 24 3.1.2 Co-seismic sources -

Atlantic Hurricane Activity During the Last Millennium

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Atlantic hurricane activity during the last millennium Michael J. Burn1 & Suzanne E. Palmer2 Received: 13 February 2015 Hurricanes are a persistent socio-economic hazard for countries situated in and around the Accepted: 10 July 2015 Main Development Region (MDR) of Atlantic tropical cyclones. Climate-model simulations have Published: 05 August 2015 attributed their interdecadal variability to changes in solar and volcanic activity, Saharan dust flux, anthropogenic greenhouse gas and aerosol emissions and heat transport within the global ocean conveyor belt. However, the attribution of hurricane activity to specific forcing factors is hampered by the short observational record of Atlantic storms. Here, we present the Extended Hurricane Activity (EHA) index, the first empirical reconstruction of Atlantic tropical cyclone activity for the last millennium, derived from a high-resolution lake sediment geochemical record from Jamaica. The EHA correlates significantly with decadal changes in tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures (SSTs; r = 0.68; 1854–2008), the Accumulated Cyclone Energy index (ACE; r = 0.90; 1851–2010), and two annually-resolved coral-based SST reconstructions (1773–2008) from within the MDR. Our results corroborate evidence for the increasing trend of hurricane activity during the Industrial Era; however, we show that contemporary activity has not exceeded the range of natural climate variability exhibited during the last millennium. The extent to which the climate dynamics of the Main Development Region (MDR) of Atlantic tropical cyclone activity are controlled by natural or anthropogenic climatic forcing factors remains unclear1,2. This uncertainty has arisen because of the reliance on historical meteorological records, which are too short to capture the natural long-term variability of climatic phenomena as well as a lack of understand- ing of the physical link between tropical Atlantic SSTs and tropical cyclone variability3,4. -

EARTH SCIENCE ACTIVITY #1 Tsunami in a Bottle

EARTH SCIENCE ACTIVITY #1 Grades 3 and Up Tsunami in a Bottle This activity is one of several in a basic curriculum designed to increase student knowledge about earthquake science and preparedness. The activities can be done at any time in the weeks leading up to the ShakeOut drill. Each activity can be used in classrooms, museums, and other educational settings. They are not sequence-bound, but when used together they provide an overview of earthquake information for children and students of various ages. All activities can be found at www.shakeout.org/schools/resources/. Please review the content background (page 3) to gain a full understanding of the material conducted in this activity. OBJECTIVE: For students to learn that tsunamis can be caused by earthquakes and to understand the effects of tsunamis on the shoreline MATERIALS/RESOURCES NEEDED: 2-liter plastic soda bottles Small gravel (fish tank gravel) Water source Empty water bottle (16 oz) Overhead projector Transparency of Tsunami Facts “What Do I See?” handout PRIOR KNOWLEDGE: In order to conduct this activity, students need to know how fault slippage can generate earthquakes. ACTIVITY: Set-Up (Time varies) Collect as many 2-liter soda bottles as possible or ask students to bring in bottles for this activity (3 students can share one bottle). Obtain an empty water bottle (about 16 oz). Remove labels from all bottles. Purchase or gather enough small gravel to fit through the mouth of the soda bottles. Students will fill up their soda bottles with gravel to create at least a 2 inch layer on the bottom of the bottle. -

Bildnachweis

Bildnachweis Im Bildnachweis verwendete Abkürzungen: With permission from the Geological Society of Ame- rica l – links; m – Mitte; o – oben; r – rechts; u – unten 4.65; 6.52; 6.183; 8.7 Bilder ohne Nachweisangaben stammen vom Autor. Die Autoren der Bildquellen werden in den Bildunterschriften With permission from the Society for Sedimentary genannt; die bibliographischen Angaben sind in der Literaturlis- Geology (SEPM) te aufgeführt. Viele Autoren/Autorinnen und Verlage/Institutio- 6.2ul; 6.14; 6.16 nen haben ihre Einwilligung zur Reproduktion von Abbildungen gegeben. Dafür sei hier herzlich gedankt. Für die nachfolgend With permission from the American Association for aufgeführten Abbildungen haben ihre Zustimmung gegeben: the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Box Eisbohrkerne Dr; 2.8l; 2.8r; 2.13u; 2.29; 2.38l; Box Die With permission from Elsevier Hockey-Stick-Diskussion B; 4.65l; 4.53; 4.88mr; Box Tuning 2.64; 3.5; 4.6; 4.9; 4.16l; 4.22ol; 4.23; 4.40o; 4.40u; 4.50; E; 5.21l; 5.49; 5.57; 5.58u; 5.61; 5.64l; 5.64r; 5.68; 5.86; 4.70ul; 4.70ur; 4.86; 4.88ul; Box Tuning A; 4.95; 4.96; 4.97; 5.99; 5.100l; 5.100r; 5.118; 5.119; 5.123; 5.125; 5.141; 5.158r; 4.98; 5.12; 5.14r; 5.23ol; 5.24l; 5.24r; 5.25; 5.54r; 5.55; 5.56; 5.167l; 5.167r; 5.177m; 5.177u; 5.180; 6.43r; 6.86; 6.99l; 6.99r; 5.65; 5.67; 5.70; 5.71o; 5.71ul; 5.71um; 5.72; 5.73; 5.77l; 5.79o; 6.144; 6.145; 6.148; 6.149; 6.160; 6.162; 7.18; 7.19u; 7.38; 5.80; 5.82; 5.88; 5.94; 5.94ul; 5.95; 5.108l; 5.111l; 5.116; 5.117; 7.40ur; 8.19; 9.9; 9.16; 9.17; 10.8 5.126; 5.128u; 5.147o; 5.147u; -

Santa Rosa County Tsunami/Rogue Wave

SANTA ROSA COUNTY TSUNAMI/ROGUE WAVE EVACUATION PLAN Banda Aceh, Indonesia, December 2004, before/after tsunami photos 1 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Purpose…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Definitions………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Assumptions……………………………………………………………. ……………………….. 4 Participants……………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Tsunami Characteristics………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Tsunami Warning Procedure…………………………………………………………………….. 6 National Weather Service Tsunami Warning Procedures…………………………………….. 7 Basic Plan………………………………………………………………………………………….. 10 Concept of Operations……………………………………………………………………………. 12 Public Awareness Campaign……………………………………………………………………. 10 Resuming Normal Operations…………………………………………………………………….13 Tsunami Evacuation Warning Notice…………………………………………………………….14 2 INTRODUCTION: Santa Rosa County Emergency Management developed a Santa Rosa County-specific Tsunami/Rogue wave Evacuation Plan. In the event a Tsunami1 threatens Santa Rosa County, the activation of this plan will guide the actions of the responsible agencies in the coordination and evacuation of Navarre Beach residents and visitors from the beach and other threatened areas. The goal of this plan is to provide for the timely evacuation of the Navarre Beach area in the event of a Tsunami Warning. An alternative to evacuating Navarre Beach residents off of the barrier island involves vertical evacuation. Vertical evacuation consists of the evacuation of persons from an entire area, floor, or wing of a building -

Re-Mapping the 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami Inundation in the Banda Aceh Region with Attention to Probable Sea Level Rise

Re-mapping the 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami Inundation in the Banda Aceh Region with Attention to Probable Sea Level Rise Elizabeth E. Webb Senior Integrative Exercise April 21, 2009 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Bachelor of Arts degree from Carleton College, Northfield, Minnesota. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract Introduction …………………………………………………………………… 1 Tectonic Background …………………………………………………………. 2 Geologic Background ……………………………………………………...…. 4 Tsunami Models ……………………………………………………………… 5 Sea Level Rise ………………………………………………………………... 8 Astronomical Tides Subsidence Climate Change Mechanisms Data Collection Models Sea Level Rise in the 20th and 21st Centuries Globally Regionally Data …………………………………………………………………………. 14 Methods ……………………………………………………………………... 16 Results ………………..……………………………………………………… 19 Linear Model Exponential Model Discussion …………………………………………………………………… 21 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………….. 23 Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………. 23 References …………………………………………………………………... 24 Re-mapping the 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami Inundation in the Banda Aceh Region with Attention to Probable Sea Level Rise Elizabeth Webb Senior Integrative Exercise, March 2009 Carleton College Advisors: Mary Savina, Carleton College Susan Sakimoto, University of Notre Dame ABSTRACT The effects of the Great Sumatra-Andaman Earthquake and the resulting tsunami on December 26, 2004 were greatest in the Banda Aceh region of northern Sumatra, where wave heights reached between 9 and 12 meters. Studies of the Sumatra-Andaman fault indicate that -

Tide-Tsunami Interactions

TIDE-TSUNAMI INTERACTIONS Zygmunt Kowalik, Tatiana Proshutinsky, Institute of Marine Science, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK, USA Andrey Proshutinsky, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA ABSTRACT In this paper we investigate important dynamics defining tsunami enhancement in the coastal regions and related to interaction with tides. Observations and computations of the Indian Ocean Tsunami usually show amplifications of the tsunami in the near-shore regions due to water shoaling. Additionally, numerous observations depicted quite long ringing of tsunami oscillations in the coastal regions, suggesting either local resonance or the local trapping of the tsunami energy. In the real ocean, the short-period tsunami wave rides on the longer-period tides. The question is whether these two waves can be superposed linearly for the purpose of determining the resulting sea surface height (SSH) or rather in the shallow water they interact nonlinearly, enhancing/reducing the total sea level and currents. Since the near–shore bathymetry is important for the run-up computation, Weisz and Winter (2005) demonstrated that the changes of depth caused by tides should not be neglected in tsunami run-up considerations. On the other hand, we hypothesize that much more significant effect of the tsunami-tide interaction should be observed through the tidal and tsunami currents. In order to test this hypothesis we apply a simple set of 1-D equations of motion and continuity to demonstrate the dynamics of tsunami and tide interaction in the vicinity of the shelf break for two coastal domains: shallow waters of an elongated inlet and narrow shelf typical for deep waters of the Gulf of Alaska.