Advances in the Study of Mega-Tsunamis in the Geological Record Raphael Paris, Kazuhisa Goto, James Goff, Hideaki Yanagisawa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

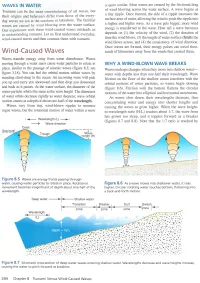

Wind-Caused Waves Misleads Us Energy Is Transferred to the Wave

WAVES IN WATER is quite similar. Most waves are created by the frictional drag of wind blowing across the water surface. A wave begins as Tsunami can be the most overwhelming of all waves, but a tiny ripple. Once formed, the side of a ripple increases the their origins and behaviors differ from those of the every day waves we see at the seashore or lakeshore. The familiar surface area of water, allowing the wind to push the ripple into waves are caused by wind blowing over the water surface. a higher and higher wave. As a wave gets bigger, more wind Our experience with these wind-caused waves misleads us energy is transferred to the wave. How tall a wave becomes in understanding tsunami. Let us first understand everyday, depends on (1) the velocity of the wind, (2) the duration of wind-caused waves and then contrast them with tsunami. time the wind blows, (3) the length of water surface (fetch) the wind blows across, and (4) the consistency of wind direction. Once waves are formed, their energy pulses can travel thou Wind-Caused Waves sands of kilometers away from the winds that created them. Waves transfer energy away from some disturbance. Waves moving through a water mass cause water particles to rotate in WHY A WIND-BLOWN WAVE BREAKS place, similar to the passage of seismic waves (figure 8.5; see Waves undergo changes when they move into shallow water figure 3.18). You can feel the orbital motion within waves by water with depths less than one-half their wavelength. -

Coastal Water Levels

Guidance for Flood Risk Analysis and Mapping Coastal Water Levels May 2016 Requirements for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Risk Mapping, Assessment, and Planning (Risk MAP) Program are specified separately by statute, regulation, or FEMA policy (primarily the Standards for Flood Risk Analysis and Mapping). This document provides guidance to support the requirements and recommends approaches for effective and efficient implementation. Alternate approaches that comply with all requirements are acceptable. For more information, please visit the FEMA Guidelines and Standards for Flood Risk Analysis and Mapping webpage (www.fema.gov/guidelines-and-standards-flood-risk-analysis-and- mapping). Copies of the Standards for Flood Risk Analysis and Mapping policy, related guidance, technical references, and other information about the guidelines and standards development process are all available here. You can also search directly by document title at www.fema.gov/library. Water Levels May 2016 Guidance Document 67 Page i Document History Affected Section or Date Description Subsection Initial version of new transformed guidance. The content was derived from the Guidelines and Specifications for Flood Hazard Mapping Partners, Procedure Memoranda, First Publication May 2016 and/or Operating Guidance documents. It has been reorganized and is being published separately from the standards. Water Levels May 2016 Guidance Document 67 Page ii Table of Contents 1.0 Topic Overview ................................................................................................................. -

Tsunami, Seiches, and Tides Key Ideas Seiches

Tsunami, Seiches, And Tides Key Ideas l The wavelengths of tsunami, seiches and tides are so great that they always behave as shallow-water waves. l Because wave speed is proportional to wavelength, these waves move rapidly through the water. l A seiche is a pendulum-like rocking of water in a basin. l Tsunami are caused by displacement of water by forces that cause earthquakes, by landslides, by eruptions or by asteroid impacts. l Tides are caused by the gravitational attraction of the sun and the moon, by inertia, and by basin resonance. 1 Seiches What are the characteristics of a seiche? Water rocking back and forth at a specific resonant frequency in a confined area is a seiche. Seiches are also called standing waves. The node is the position in a standing wave where water moves sideways, but does not rise or fall. 2 1 Seiches A seiche in Lake Geneva. The blue line represents the hypothetical whole wave of which the seiche is a part. 3 Tsunami and Seismic Sea Waves Tsunami are long-wavelength, shallow-water, progressive waves caused by the rapid displacement of ocean water. Tsunami generated by the vertical movement of earth along faults are seismic sea waves. What else can generate tsunami? llandslides licebergs falling from glaciers lvolcanic eruptions lother direct displacements of the water surface 4 2 Tsunami and Seismic Sea Waves A tsunami, which occurred in 1946, was generated by a rupture along a submerged fault. The tsunami traveled at speeds of 212 meters per second. 5 Tsunami Speed How can the speed of a tsunami be calculated? Remember, because tsunami have extremely long wavelengths, they always behave as shallow water waves. -

Tsunamis in Alaska

Tsunami What is a Tsunami? A tsunami is a series of traveling waves in water that are generated by violent vertical displacement of the water surface. Tsunamis travel up to 500 mph across deep water away from their generation zone. Over the deep ocean, there may be very little displacement of the water surface; but since the wave encompasses the depth of the water column, wave amplitude will increase dramatically as it encounters shallow coastal waters. In many cases, a El Niño tsunami wave appears like an endlessly onrushing tide which forces its way around through any obstacle. The image on the left illustrates how the amplitude of a tsunami wave increases as it moves from the deep ocean water to the shallow coast. Over deep water, the wave length is long, and the wave velocity is very fast. By the time the wave reaches the coast, wave length decreases quickly and wave speed slows dramatically. As this takes place, wave height builds up as it prepares to inundate the shore. Why do Tsunamis occur in Alaska? Subduction-zone mega-thrust earthquakes, the most powerful earthquakes in the world, can produce tsunamis through fault boundary rupture, deformation of an overlying plate, and landslides induced by the earthquake (IRIS, 2016). Megathrust earthquakes occur along subduction zones, such as those found along the ring of fire (see image to the right). The ring of fire extends northward along the coast of western North America, then arcs westward along the southern side of the Aleutians, before curving southwest along the coast of Asia. -

2018 NOAA Science Report National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S

2018 NOAA Science Report National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Technical Memorandum NOAA Research Council-001 2018 NOAA Science Report Harry Cikanek, Ned Cyr, Ming Ji, Gary Matlock, Steve Thur NOAA Silver Spring, Maryland February 2019 NATIONAL OCEANIC AND NOAA Research Council noaa ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION 2018 NOAA Science Report Harry Cikanek, Ned Cyr, Ming Ji, Gary Matlock, Steve Thur NOAA Silver Spring, Maryland February 2019 UNITED STATES NATIONAL OCEANIC National Oceanic and DEPARTMENT OF AND ATMOSPHERIC Atmospheric Administration COMMERCE ADMINISTRATION Research Council Wilbur Ross RDML Tim Gallaudet, Ph.D., Craig N. McLean Secretary USN Ret., Acting NOAA NOAA Research Council Chair Administrator Francisco Werner, Ph.D. NOAA Research Council Vice Chair NOTICE This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency or Contractor thereof. Neither the United States Government, nor Contractor, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Mention of a commercial company or product does not constitute an endorsement by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. -

The Kingdom of Tonga Devastated by a Megatsunami in the Mid-15Th Century

EGU21-5317, updated on 25 Sep 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-5317 EGU General Assembly 2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. The kingdom of Tonga devastated by a megatsunami in the mid-15th century Franck Lavigne1,2,3, Julie Morin4, Wassmer Patrick2, Weller Olivier5, Kula Taaniela6, Ana V. Maea6, Karim Kelfoun7, Fatima Mokadem2, Raphael Paris7, Mukhamad N. Malawani1,2,8, Faral Audrey1,2, Mhammed Benbakkar7, Ségolène Saulnier-Copard2, Céline M. Vidal4, Tu’I’ahai Tu’I’afitu6, Gomez Christopher9, and Fuka Kitekei’aho10 1Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne University, ([email protected]) 2Laboratory of Physical Geography, UMR 8591 CNRS, Meudon, France 3Institut Universitaire de France, Paris, France 4Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 5Trajectoires, UMR 8215 CNRS, Paris, France 6Ministry of Land and Natural Resources, Natural Resources Division, Nuku'alofa, Kingdom of Tonga 7Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans, Université Clermont Auvergne, CNRS, IRD, OPGC, France 8Faculty of Geography, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 9Laboratory of Sediment Hazards and Disaster Risk, Kobe University, Japan 10Geocare & Petroleum Consult Ltd, Nuku'alofa, Kingdom of Tonga The pre-colonial history of Tonga and West Polynesia still suffers from major gaps because its reconstruction is essentially based on legends left by oral tradition, and by archaeological evidence somehow difficult to interpret. By the fourteenth century, the powerful Tu'i Tonga kingdom united the islands of the Tongan archipelago under a centralised authority and, according to tradition, extended its influence to neighbouring island groups in the Central Pacific. However, some periods of deep crisis were identified, e.g. -

Numerical Calculation of Seiche Motions in Harbours of Arbitrary Shape

NUMERICAL CALCULATION OF SEICHE MOTIONS IN HARBOURS OF ARBITRARY SHAPE P. Gaillard Sogreah, Grenoble, France ABSTRACT A new method of calculation of wave diffraction around islands, off- shore structures, and of long wave oscillations within offshore or shore-connected harbours is presented. The method is a combination of the finite element technique with an analytical representation of the wave pattern in the far field. Examples of application are given, and results are compared with other theoretical and experimental investig- ations. INTRODUCTION The prediction of possible resonant response of harbours to long wave excitation may be an important factor at the design stage. Hydraulic scale models have the disadvantage of introducing some bias in the results due to wave reflection on the wave paddle and on the tank boundaries. Numerical methods on the other hand can avoid such spurious effects by an appropriate representation of the unbounded water medium outside the harbour. Various numerical methods exist for calculating the seiche motions in harbours of arbitrary shape and water depth configuration. Among these, the hybrid-element methods, as described by Berkhoff [l] , Bettess and Zienkiewicz [2] , Chen and Mei [3j , Sakai and Tsukioka [8] use a com- bination of the finite element technique with other methods for repre- senting the velocity potential within the harbour and in the offshore zone. This paper presents a new method based on the same general approach, with an analytical representation of the wave pattern in the far field. It differs from the former methods in several aspects stressed hereafter. We consider here two kinds of applications: a) the first is the study of wave diffraction by islands or bottom seated obstacles in the open sea and the study of wave oscil- lations within and around an offshore harbour. -

Literature Review of Tsunami Sources Affecting Tsunami Hazard Along the US East Coast

Literature review of tsunami sources affecting tsunami hazard along the US East Coast Department of Ocean Engineering, University of Rhode Island Narragansett, USA Feb. 21, 2011 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND ...................................................................................................................... 3 2. LITERATURE REVIEW OF RELEVANT TSUNAMI SOURCES .................................... 5 2.1 Submarine Mass Failures ........................................................................................................ 5 2.2 Co-seismic tsunamis .................................................................................................................. 8 2.2.1 Review of literature on Caribbean subduction zone ............................................................. 8 2.2.2 NOAA Forecast Source Database for Caribbean subduction zone ............................... 16 2.2.3 Azores-Gibraltar convergence zone .......................................................................................... 17 2.3 Cumbre Vieja Volcano flanK collapse ............................................................................... 21 3. INITIAL SOURCE DEFINITIONS AND TSUNAMI SIMULATIONS .......................... 24 3.1 Modeling methodology .......................................................................................................... 24 3.1.1 Initial conditions for model .......................................................................................................... 24 3.1.2 Co-seismic sources -

Atlantic Hurricane Activity During the Last Millennium

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Atlantic hurricane activity during the last millennium Michael J. Burn1 & Suzanne E. Palmer2 Received: 13 February 2015 Hurricanes are a persistent socio-economic hazard for countries situated in and around the Accepted: 10 July 2015 Main Development Region (MDR) of Atlantic tropical cyclones. Climate-model simulations have Published: 05 August 2015 attributed their interdecadal variability to changes in solar and volcanic activity, Saharan dust flux, anthropogenic greenhouse gas and aerosol emissions and heat transport within the global ocean conveyor belt. However, the attribution of hurricane activity to specific forcing factors is hampered by the short observational record of Atlantic storms. Here, we present the Extended Hurricane Activity (EHA) index, the first empirical reconstruction of Atlantic tropical cyclone activity for the last millennium, derived from a high-resolution lake sediment geochemical record from Jamaica. The EHA correlates significantly with decadal changes in tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures (SSTs; r = 0.68; 1854–2008), the Accumulated Cyclone Energy index (ACE; r = 0.90; 1851–2010), and two annually-resolved coral-based SST reconstructions (1773–2008) from within the MDR. Our results corroborate evidence for the increasing trend of hurricane activity during the Industrial Era; however, we show that contemporary activity has not exceeded the range of natural climate variability exhibited during the last millennium. The extent to which the climate dynamics of the Main Development Region (MDR) of Atlantic tropical cyclone activity are controlled by natural or anthropogenic climatic forcing factors remains unclear1,2. This uncertainty has arisen because of the reliance on historical meteorological records, which are too short to capture the natural long-term variability of climatic phenomena as well as a lack of understand- ing of the physical link between tropical Atlantic SSTs and tropical cyclone variability3,4. -

Bildnachweis

Bildnachweis Im Bildnachweis verwendete Abkürzungen: With permission from the Geological Society of Ame- rica l – links; m – Mitte; o – oben; r – rechts; u – unten 4.65; 6.52; 6.183; 8.7 Bilder ohne Nachweisangaben stammen vom Autor. Die Autoren der Bildquellen werden in den Bildunterschriften With permission from the Society for Sedimentary genannt; die bibliographischen Angaben sind in der Literaturlis- Geology (SEPM) te aufgeführt. Viele Autoren/Autorinnen und Verlage/Institutio- 6.2ul; 6.14; 6.16 nen haben ihre Einwilligung zur Reproduktion von Abbildungen gegeben. Dafür sei hier herzlich gedankt. Für die nachfolgend With permission from the American Association for aufgeführten Abbildungen haben ihre Zustimmung gegeben: the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Box Eisbohrkerne Dr; 2.8l; 2.8r; 2.13u; 2.29; 2.38l; Box Die With permission from Elsevier Hockey-Stick-Diskussion B; 4.65l; 4.53; 4.88mr; Box Tuning 2.64; 3.5; 4.6; 4.9; 4.16l; 4.22ol; 4.23; 4.40o; 4.40u; 4.50; E; 5.21l; 5.49; 5.57; 5.58u; 5.61; 5.64l; 5.64r; 5.68; 5.86; 4.70ul; 4.70ur; 4.86; 4.88ul; Box Tuning A; 4.95; 4.96; 4.97; 5.99; 5.100l; 5.100r; 5.118; 5.119; 5.123; 5.125; 5.141; 5.158r; 4.98; 5.12; 5.14r; 5.23ol; 5.24l; 5.24r; 5.25; 5.54r; 5.55; 5.56; 5.167l; 5.167r; 5.177m; 5.177u; 5.180; 6.43r; 6.86; 6.99l; 6.99r; 5.65; 5.67; 5.70; 5.71o; 5.71ul; 5.71um; 5.72; 5.73; 5.77l; 5.79o; 6.144; 6.145; 6.148; 6.149; 6.160; 6.162; 7.18; 7.19u; 7.38; 5.80; 5.82; 5.88; 5.94; 5.94ul; 5.95; 5.108l; 5.111l; 5.116; 5.117; 7.40ur; 8.19; 9.9; 9.16; 9.17; 10.8 5.126; 5.128u; 5.147o; 5.147u; -

Continuous Seiche in Bays and Harbors

Manuscript prepared for Ocean Sci. with version 2014/07/29 7.12 Copernicus papers of the LATEX class copernicus.cls. Date: 14 February 2016 Continuous seiche in bays and harbors J. Park1, J. MacMahan2, W. V. Sweet3, and K. Kotun1 1National Park Service, 950 N. Krome Ave, Homestead, FL, USA 2Naval Postgraduate School, 833 Dyer Rd., Monterey, CA 93943, USA 3NOAA, 1305 East West Hwy, Silver Spring, MD, USA Correspondence to: J. Park ([email protected]) Abstract. Seiches are often considered a transitory phenomenon wherein large amplitude water level oscillations are excited by a geophysical event, eventually dissipating some time after the event. However, continuous small–amplitude seiches have been recognized presenting a question as to the origin of continuous forcing. We examine 6 bays around the Pacific where continuous seiches 5 are evident, and based on spectral, modal and kinematic analysis suggest that tidally–forced shelf– resonances are a primary driver of continuous seiches. 1 Introduction It is long recognized that coastal water levels resonate. Resonances span the ocean as tides (Darwin, 1899) and bays as seiches (Airy, 1877; Chrystal, 1906). Bays and harbors offer refuge from the open 10 ocean by effectively decoupling wind waves and swell from an anchorage, although offshore waves are effective in driving resonant modes in the infragravity regime at periods of 30 s to 5 minutes (Okihiro and Guza, 1996; Thotagamuwage and Pattiaratchi, 2014), and at periods between 5 minutes and 2 hours bays and harbors can act as efficient amplifiers (Miles and Munk, 1961). Tides expressed on coasts are significantly altered by coastline and bathymetry, for example, 15 continental shelves modulate tidal amplitudes and dissipate tidal energy (Taylor, 1919) such that tidally–driven standing waves are a persistent feature on continental shelves (Webb, 1976; Clarke and Battisti, 1981). -

TSUNAMI and SEICHE

TSUNAMI and SEICHE DEFINITIONS: Seiche – The action of a series of standing waves (sloshing action) of an enclosed body or partially enclosed body of water caused by earthquake shaking. Seiche action can affect harbors, bays, lakes, rivers, and canals. Tsunami – A sea wave of local or distant origin that results from large-scale displacements of the seafloor associated with large earthquakes, major submarine slides, or exploding volcanic islands. BACKGROUND INFORMATION: Tsunami The Pacific Coast of Washington is at risk from tsunamis. These destructive waves can be caused by coastal or submarine landslides or volcanism, but they are most commonly caused by large submarine earthquakes. Tsunamis are generated when these geologic events cause large, rapid movements in the sea floor that displace the water column above. That swift change creates a series of high-energy waves that radiate outward like pond ripples. Offshore tsunamis would strike the adjacent shorelines within minutes and also cross the ocean at speeds as great as 600 miles per hour to strike distant shores. In 1946, a tsunami was initiated by an earthquake in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska; in less than 5 hours, it reached Hawaii with waves as high as 55 feet and killed 173 people. Tsunami waves can continue for hours. The first wave can be followed by others a few minutes or a few hours later, and the later waves are commonly larger. The first wave to strike Crescent City, California, caused by the Alaska earthquake in Prince William Sound in 1964, was 9 feet above the tide level; the second, 29 minutes later, was 6 feet above tide, the third was about 11 feet above the tide level, and the fourth, most damaging wave was more than 16 feet above the tide level.