How Might Access for Vehicles Have Prevented the Economic Failure of the Thames Tunnel 1843-1865?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Brunel : the Man Who Built the World Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BRUNEL : THE MAN WHO BUILT THE WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Steven Brindle | 208 pages | 20 Apr 2021 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780753821251 | English | London, United Kingdom Brunel : The Man Who Built the World PDF Book The West End Museum. The Importance of Being Earnest. Bibliografische Informationen. Branch Home. After a hard day spent in preparing and delivering evidence, and a hasty dinner, he would attend consultations till a late hour; and then, secure against interruption, sit down to his papers, and draw specifications, write letters or reports, or make calculations all through the night. The patented system came from shipbuilders and engineers Joseph and Jacob Samuda who, along with gas engineer Samuel Clegg, were able to produce encouraging tests in London. At just over 5ft 1. The title, at first, seems impossibly hyperbolic, because it is: Isambard Kingdom Brunel did not, in fact, build the world. When he returned to England his father was working on an ambitious project to build a tunnel under the River Thames and Brunel joined him as his apprentice. Brunel took up the call and constructed a wooden and canvas pre-fabricated hospital that so greatly improved sanitary conditions that deaths were said to have fallen by ten times the usual amount. Hawking's warnings: What he predicted for the future. Although the son was never knighted, the father became Sir Marc in He desperately sought affirmation through his work, craving public approval rather than fame. In his talk, Robert Hulse will examine Brunel as not only as visionary engineer, but also as showman. Having read the book I have concluded that Brunel was a genius and I do not use that word lightly. -

Isambard Kingdom Brunel Engineering Modern Britain

MARTIN RANDALL TRAVEL ART • ARCHITECTURE • GASTRONOMY • ARCHAEOLOGY • HISTORY • MUSIC • LITERATURE Isambard Kingdom Brunel Engineering Modern Britain 5–10 September 2021 (mh 879) 6 days • £2,360 Lecturer: Anthony Lambert Examines the life and work of one of the greatest engineers and inventors of all time. Visits most of Brunel’s major surviving structures in London and the Southwest. Special arrangements include lunch on SS Great Britain. Stays in two former Great Western Railway hotels. Isambard Kingdom Brunel is the most famous and arguably the greatest engineer of Victorian Britain, an era when the achievements of the profession were often hailed, quite justifiably, as ‘heroic’. None of his contemporaries was as versatile, and none was entrusted with projects Clifton Suspension Bridge, near Bristol, wood engraving c. 1880. on such a scale at so young an age – he was just 27 when he was made engineer of the Great steamship Great Britain, displayed at the dock Day 3: Maidenhead, Didcot, Box. The journey Western Railway (GWR). in which she was built in 1843, and the fine to Bristol is by coach, enabling us to stop at Trained under his French father, Marc, archive of Brunel material in the adjacent key Brunel creations along the route. See Brunel designed dockyards, a prefabricated multi-award-winning Being Brunel museum. Maidenhead Bridge, the replica broad-gauge hospital for Florence Nightingale, tunnels, One of the former broad-gauge railways in locomotives and carriage and re-erected bridges, viaducts and railway stations. One Devon is now a steam-worked heritage railway, transshipment shed at the Didcot Railway of his ocean-going steamships was the first and the tour concludes with Brunel’s last great Centre, and the portal to Box Tunnel, once the to be propeller-driven (his design being only work, the Royal Albert Bridge over the Tamar world’s longest. -

Site Liaison Brunel Museum Thames Tunnel

Joint Guild/APTG Site Checklist Template 2019 ! ! Site Name BRUNEL MUSEUM - THAMES TUNNEL Address/Website Brunel Museum Railway Avenue Rotherhithe London, SE16 4LF https://www.brunel-museum.org.uk/ Site Liaison Rep Name and Contact Jackie Clare Details [email protected] Opening Hours and Admission Details Open: 7 days/week (except 31/12 + 1/1) 10 am - 5 pm + Check website for special events with evening opening Admission to Museum (exhibition in former En- gine House + Grand Entrance Hall): Full price: £6/person Concessions (> 60 yrs + students with ID) £4/person Under 16 years - free entry Blue Badge Guides (with clients or to recce) + Blue Badge Guides in training - free entry Admission of more than 3 visitors to Grand En- trance Hall only - maximum 10 minute slot: £20 donation per group * Admission of up to 3 visitors to Grand Entrance Hall only - maximum 10 minute slot: free entry (please encourage a donation - the museum is run entirely by volunteers). (* See details under Site Specific Guiding Rules) Joint Guild/APTG Site Checklist Template 2019 ! ! Site Name BRUNEL MUSEUM - THAMES TUNNEL Site Specific Guiding Rules The possibility to visit the Grand Entrance Hall only for a 5 - 10 minute presentation by the guide is a privilege granted to Blue Badge Guides and is aimed at guides on a walk through the area rather than specifically visiting the Brunel Museum. The time limits should be strictly observed and guides should operate around and give way to any other activities going on in the Grand Entrance Hall at the time of their visit. Please send an email to the museum info@brunel- museum.org.uk before your visit with your estimated arrival time and numbers. -

Media Briefing Note – Crossrail's

MEDIA BRIEFING NOTE – CROSSRAIL’S FIRST TBM UNVEILED About Crossrail: Crossrail is Europe’s largest construction project with a total funding envelope of £14.8bn - it will deliver a 118 kilometre rail line that will link Maidenhead and Heathrow in the west with Shenfield and Abbey Wood in the east via 21km of twin-bored tunnels under London. When completed Crossrail will bring an extra 1.5 million people to within 45 minutes of London. Crossrail will increase the capacity of London’s rail based public transport network by 10%. It will link London’s key employment, leisure and business districts – Heathrow, West End, the City and Docklands – enabling further economic development to take place. Passengers will be able to travel from Heathrow to Tottenham Court Road in under 30 minutes and Paddington to Canary Wharf in 16 minutes. More than 3,000 people are now employed on Europe’s largest infrastructure project. - 1 - Thousands more will be employed in building Crossrail at the height of construction in 2013-15. Further jobs will be supported through the supply chain in London and in regionally-based manufacturers and suppliers. At least 400 apprenticeships will be created through Crossrail’s contractors. The new Tunnelling and Underground Construction Academy in east London welcomed its first students in September and will train up to 3,500 people with the skills required to work below ground. The Academy will be fully open by early 2012. Whist the UK has tunnelling expertise and knowledge this is the first purpose- built training facility in the UK to act as a focal point for the industry. -

THE Ss GREAT BRITAIN

THE LIFE, DEATH AND RESURRECTION OF THE ss GREAT BRITAIN By Ken McNaughton This is the story of two men and a ship. Isambard Kingdom Brunel was chief engineer for the great Western Railway from London to Bristol, and designer of the Clifton Suspension Bridge and the ss Great Britain (Fig. 1). The ship had a long and productive career, was scuttled in the Falkland Islands in 1937, towed back to Bristol in 1970 and has since won a string of awards as an outstanding museum. I visited the ship in June 2008. John Ross McNaughton was a working-class Scot who left for Australia with his wife and one-year old daughter in 1838, started a dynasty in Melbourne, and returned to the United Kingdom with his wife and 14-year old son on board the ss Great Britain in 1874. He was my great great grandfather. Figure 1. The ss Great Britain, with six masts and one funnel, on 26 June 2008 in the dry dock where she was launched by Prince Albert on 19 July 1843. ISAMBARD KINGDOM BRUNEL Isambard Kingdom Brunel (Fig. 2) was born 9 April 1806 to Sophia Kingdom and Sir Marc Isambard Brunel [1]. At age 20 he was appointed chief assistant engineer of the Thames Tunnel—his father’s greatest achievement—which still runs beneath the river from Rotherhithe to Wapping. In 1830, when he was only 23, Brunel’s design was adopted for the Clifton Bridge, to span the deep gorge of the Avon River and unite Bristol in the east with the country to the west (Fig. -

Tunnel Books

Tu n n e l B o o k s Peepshow depicting the River Thames and tunnel, about 1843, Britain. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Photograph: Dennis Crompton Tunnel books, (sometimes also known as peep show books) were first used by the victorians to mark the opening of grand historical events and significant engineering events . Usually pocket sized, these books show paper cut out scenes and expand to give an illusion of depth. The other book illustrated here, depicts the opening of the Great Exhibition in 1851. The opening of the Thames Tunnel The Thames Tunnel, was the first tunnel in the world to be built under a river. Work first started in 1824 on the tunnel to pass under the River Thames and connected Rotherhithe to Wapping. It was meant to transport goods under an already congested river but the project proved to be extremely difficult and hazardous. On its completion, Marc Brunel was knighted in recognition of his achievement however, due to lack of funds and issues with flooding, the tunnel could not at that time be used for the horse drawn transport it was intended. Instead, it was decided to open the tunnel to foot passengers and indeed the tunnel proved to be very popular. On opening day 50,000 people walked through it, and about half the population of London in 1843, visited during the first 10 weeks, all paying a penny each. Shops were set up in the cross arches and the Thames Tunnel book was created to mark the occasion. Train tracks were laid much later and the first steam train ran through it on 7th December 1869. -

Welcome to This Discussion Concerning the Rag Morris

Gavin Skinner, The Brunel play, Mummers Unconvention, Bath, 2011. The Brunel play Some of you may have been lucky enough to see the play at the unplugged concert on the opening night of the 2011 Bath Mummers Unconvention or at our previous performances in Bristol in 2009, or at this year’s Bristol Folk Festival where it was performed on stage at the Colston Hall. There was another chance to see it on the Saturday of the Unconvention, when we took it out on to the streets of Bath. Figure One: The Brunel Play unplugged. Photo: www.folkfestivalphotos.co.uk I’m going to be looking into some of the questions I’ve been asking myself about the play since the inception of the project about 3 years ago; and how the answers to those questions informed the development of the play, looking at aspects of the performance, production and the philosophy. 49 Gavin Skinner, The Brunel play, Mummers Unconvention, Bath, 2011. Bristol’s Rag Morris used to have more of a tradition of performing self-penned plays, though the last major production had been 1993, a year before I started dancing regularly with Rag. This play about the legendary Bristolian giants, Vincent and Goram, had been penned by Marc Vyvan-Jones with help from Roland & Linda Clare. These two giants had a test of strength to win the hand of the fair Princess Sabrina, and to prove his worth; Vincent carved out the Avon Gorge with a pickaxe. The script for this play included the character of Brunel-zebub, as the devil with the frying pan who was raising funds to build a bridge to span St Vincent’s Rocks. -

TWJ 138 AA SCHOOLS ISAMBARD.Indd

Junior SCHOOLS All about Isambard Kingdom Brunel All about Isambard Kingdom Brunel Record-breaking ships Brunel: engineer, entrepreneur and designer Brunel’s SS It is 175 years since Brunel’s SS Great Great Eastern. You can visit Britain was launched in Bristol. the SS Great EARLY n 19 July 1843, the SS Great Britain was Britain in STARTER Bristol. Olaunched in Bristol. At 98 metres long, it was the Isambard Kingdom Brunel largest ship in the world at the time. This magnifi cent would o en get up at 3am creation was the work of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, to take a horse-drawn a 19th-century engineer who designed ships, stagecoach to work. Before the SS Great Britain, Brunel had already bridges, tunnels and railway lines. designed the SS Great Western, which The SS Great Britain is said to have set the launched in 1837. It was the fi rst steam- standards for the design of modern ships, shaping the powered ship to regularly cross the Atlantic future of passenger travel on a large scale –it could Ocean, travelling on its fi rst voyage from carry hundreds of people over great distances. In Bristol to New York in 15 days – half the time it 1874 it took travellers to Australia, on a journey that took sailing ships to make the same crossing. took about 60 days. It remained in service until 1933. In 1858, 15 years after SS Great Britain was The ship eventually returned to Bristol on 19 July launched, Brunel’s SS Great Eastern took to the 1970, 127 years to the day after it was launched. -

VI APPENDIX 2 WILLIAM GRAVATT and the GWR BRIDGES Just One

APPENDIX 21 WILLIAM GRAVATT AND THE GWR BRIDGES Just one month before the first GWR Bill was thrown out of the Lords on 25 July 1834, Gravatt stated that Brunel had been employing him 'for some time … in making Calculations for the Great Western Railway,' without actually specifying what those 'calculations' related to. 2 Later, in a printed letter to the B&ER shareholders he made the following explicit claim: I drew up the contracts, and designed all the bridges and culverts, and 'things of that kind,' on the Bristol and Exeter Railway, as I had before done on the greater part of the Great Western .3 This Appendix investigates evidence relating to the extent of Gravatt's involvement in the design of the GWR, and the design of GWR bridges in particular, during two phases: firstly, up to the rejection of the first GWR Bill and, secondly, from that time up to July 1836 when Gravatt was appointed Resident Engineer on the B&ER. Brunel kept two office diaries in 1834, one of which is a sporadic series of brief, disjointed entries – in effect, memoranda of appointments and topics.4 The other diary is a daily record of his engagements and the projects in which he was occupied, with expences and payments apportioned to each project, no doubt as an aid to invoicing clients.5 The parliamentary survey for the GWR was deposited on 30 November 1833 and the GWR's London Committee authorised Brunel to 'commence the requisite borings and other examinations required to verify the estimates in Parliament' on 16 January 1834; consequently, his engagement diary entries after mid-January 1834 relate predominantly to GWR matters. -

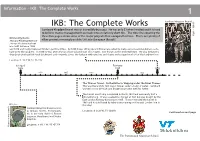

IKB: the Complete Works 1

Information - IKB: The Complete Works 1 Isambard Kingdom Brunel ( 1 8 0 IKB: The Complete Works 6 - Isambard Kingdom Brunel was an incredibly busy guy. He was only 53 when he died and it is hard 1 8 5 to believe that he managed to fit so much into a relatively short life. The time line covering the 9 these two pages shows some of the major projects that occupied his time. There are plenty of ) Bristol City Docks. Jessops Floating Harbour other projects we simply couldn’t fit into the space though! Jessops Floating Harbour was built between 1804 and 1810 and vastly improved Bristol’s port facilities. By 1830 it was silting up and Brunel was asked to make some recommendations as to how to fix the problem. In 1833 he was given the go ahead to build four sluice gates, now known as the Underfall Dam. He also designed a drag-boat which pulled itself backwards and forwards across the harbour with winches and chains and scraped mud off of the harbour floor. Location: 2°36.2’W; 51°26.9’N 9th April February 1806 1825 1833 1810 1815 1820 1830 The Thames Tunnel. Rotherhithe to Wapping under the River Thames This was the world’s first major tunnel under a body of water. Isambard worked on this difficult and dangerous project with his father. The tunnel was finally completed in March 1843 and was nearly half a kilometre long. It was a pedestrian tunnel at first but was bought by the East London Railway Company in 1865. -

The Arup Journal Ground Engineering 18 Nick O'riordan Marks a Special Moment When Our Creative Capability, Design Flare, and Ability to Deliver Have Become Tangible

.THEARUP JOURNAL ARUP CLIENT: ................._ ___ .. Jtn..._ Union Railways (wholly-owned subsidiary of l/11/llll London & Continental Railways Ltd) I/Ill/Ill un on RfEl/1/1/l lll DESIGNER AND PROJECT MANAGER: RAILWAYS LCR RAILUNK Rail Link Engineering (Arup, Bechtel, Halcrow, Systra) Published by Arup, 13 Fitzroy Street, London WH 4BQ, UK. Tel: +44 (0)20 7636 1531 Fax: +44 (0)20 7580 3924 e-mail: [email protected] www.arup.com Foreword Contents Foreword Terry Hill 2 Terry Hill Chairman, Arup The CTRL and Arup: Section 1 of the 109km Channel Tunnel Rail Link was opened by the UK 3 Introduction to the history Prime Minister Tony Blair on 28 September 2003 . With this opening came Mike Glover the first and long-awaited benefits of high-speed rail travel in Britain. Involving Safety - an industry-high safety record for construction - has been achieved 6 the communities and now travel will become safer and more convenient. Since the opening, Lisa Doughty the number of passengers using Eurostar, the London to Paris/Brussels Media relations high-speed rail seNice, has increased by 20%, and reliability has soared. 9 Lisa Doughty Paul Ravenscroft This is due to the commitment of a tremendous team of people in Arup and our partners in Rail Link Engineering, and the client's team in Union Rail safety Railways, who have brought a new catch phrase to railway construction - 10 Lorna Small 'on time, on budget'. CTRL and the environment It is also due in no small way to the creativity and innovation of Arup, for it 12 Paul Johnson was our firm that perceived the need for this project, conceived the solution, and has been delivering the result.