The Roman Maritime Concrete Study (ROMACONS)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter (1) Introduction

Chapter (1) Introduction 1.1 General: Considering the need for low-cost construction materials especially in the rural areas in Sudan, the production, and the use of the durable low cost building materials such as lime and Pozzolana which are available in big quantities in many parts of the Sudan, become of very great importance. Pozzolana and lime can be produced with much less sophisticated technology than Portland cement. This means that Pozzolana and lime can be produced at relatively low cost and requires much less Pozzolana exchange than cement. Like many other developing countries Sudan suffers from housing shortage against the ever increasing demand not only due to the continuous displacement from rural to urban areas because of war, drought and natural disasters, but also dwellings are needed for returnees after peace. Conventional materials, such as concrete, timber, bricks and steel, used in walls and roofs, which contribute up to over 90% of the cost of low cost dwelling, are beyond the reach of most of the poor population. On the other hand traditional materials, mainly earth products and thatch, are subject to weathering, insect attack and fire hazard. The solution to this problem is thought to be by using substitute materials produced or developed from traditional construction materials to reduce the cost to a minimum. Soil, being one of the traditional materials, offers many advantages when used as construction material. These include availability, ease of use, cheapness, suitability to most parts of the building, and that it is environment friendly. The disadvantages of soil are being less durable, poor in tension, lacking of acceptability among social groups and institutions. -

In This Study, Marcello Mogetta Examines the Origins and Early Dissemina- Tion of Concrete Technology in Roman Republican Architecture

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-84568-7 — The Origins of Concrete Construction in Roman Architecture Marcello Mogetta Frontmatter More Information THE ORIGINS OF CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION IN ROMAN ARCHITECTURE In this study, Marcello Mogetta examines the origins and early dissemina- tion of concrete technology in Roman Republican architecture. Framing the genesis of innovative building processes and techniques within the context of Rome’s early expansion, he traces technological change in monumental construction in long-established urban centers and new Roman colonial cites founded in the 2nd century BCE in central Italy. Mogetta weaves together excavation data from both public monu- ments and private domestic architecture that previously have been studied in isolation. Highlighting the organization of the building industry, he also explores the political motivations and cultural aspirations of patrons of monumental architecture, reconstructing how they negotiated economic and logistical constraints by drawing from both local traditions and long- distance networks. By incorporating the available scientific evidence into the development of concrete technology, Mogetta also demonstrates the contributions of anonymous builders and contractors, shining a light on their ability to exploit locally available resources. marcello mogetta is a Mediterranean archaeologist whose research focuses on early Roman urbanism in Italy. He conducts primary fieldwork at the sites of Gabii (Gabii Project) and Pompeii (Venus Pompeiana Project), for which he has received multiple grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Loeb Classical Library Foundation, the AIA, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. He coordinates the CaLC-Rome Project, an international collaboration that applies 3D mod- eling and surface analysis to the life cycle of ceramic vessels from the Esquiline necropolis in Rome. -

On the Structure of the Roman Pantheon 25

College Art Association http://www.jstor.org/stable/3050861 . Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Art Bulletin. http://www.jstor.org On the Structureof the Roman Pantheon Robert Mark and Paul Hutchinson Since the time of its construction, the bold, brilliantly simple schema of Hadrian's Pantheon has inspired much emulation, commendation, and even fear. Modern commentators tend to view the building as a high point in an "architectural rev- olution" brought about mainly through the Roman development of a superior poz- zolana concrete that lent itself to the forming of unitary, three-dimensional struc- tures. -

Guide to Concrete Repair Second Edition

ON r in the West August 2015 Guide to Concrete Repair Second Edition Prepared by: Kurt F. von Fay, Civil Engineer Concrete, Geotechnical, and Structural Laboratory U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Technical Service Center August 2015 Mission Statements The U.S. Department of the Interior protects America’s natural resources and heritage, honors our cultures and tribal communities, and supplies the energy to power our future. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Acknowledgments Acknowledgment is due the original author of this guide, W. Glenn Smoak, for all his efforts to prepare the first edition. For this edition, many people were involved in conducting research and field work, which provided valuable information for this update, and their contributions and hard work are greatly appreciated. They include Kurt D. Mitchell, Richard Pepin, Gregg Day, Jim Bowen, Dr. Alexander Vaysburd, Dr. Benoit Bissonnette, Maxim Morency, Brandon Poos, Westin Joy, David (Warren) Starbuck, Dr. Matthew Klein, and John (Bret) Robertson. Dr. William F. Kepler obtained much of the funding to prepare this updated guide. Nancy Arthur worked extensively on reviewing and editing the guide specifications sections and was a great help making sure they said what I meant to say. Teri Manross deserves recognition for the numerous hours she put into reviewing, editing and formatting this Guide. The assistance of these and numerous others is gratefully acknowledged. Contents PART I: RECLAMATION'S METHODOLOGY FOR CONCRETE MAINTENANCE AND REPAIR Page A. -

Guide to Safety Procedures for Vertical Concrete Formwork

F401 Guide to Safety Procedures for Vertical Concrete Formwork SCAFFOLDING, SHORING AND FORMING INSTITUTE, INC. 1300 SUMNER AVENUE, CLEVELAND, OHIO 44115 (216) 241-7333 F401 F O R E W O R D The “Guide to Safety Procedures for Vertical Concrete Formwork” has been prepared by the Forming Section Engineering Committee of the Scaffolding, Shoring & Forming Institute, Inc., 1300 Sumner Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio 44115. It is suggested that the reader also refer to other related publications available from the Scaffolding, Shoring & Forming Institute. The SSFI welcomes any comments or suggestions regarding this publication. Contact the Institute at the following address: Scaffolding, Shoring and Forming Institute, 1300 Sumner Ave., Cleveland, OH 44115. i F401 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ........................................................................................ 1 Section 1 - General................................................................................ 2 Section 2 - Erection of Formwork......................................................... 2 Section 3 - Bracing................................................................................ 3 Section 4 - Walkways/Scaffold Brackets.............................................. 3 Section 5 - Special Applications........................................................... 4 Section 6 - Inspection............................................................................ 4 Section 7 - Concrete Placing................................................................. 5 Section -

Effect of Formwork Removal Time Reduction on Construction

applied sciences Article Effect of Formwork Removal Time Reduction on Construction Productivity Improvement by Mix Design of Early Strength Concrete 1, 2, 3 3, 3 Taegyu Lee y , Jaehyun Lee y, Jinsung Kim , Hyeonggil Choi * and Dong-Eun Lee 1 Department of Fire and Disaster Prevention, Semyung University, 65 Semyung-ro, Jecheon-si, Chungbuk 27136, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Safety Engineering, Seoul National University of Science and Technology, 232 Gongneung-ro, Nowon-gu, Seoul 01811, Korea; [email protected] 3 School of Architecture, Civil, Environment, and Energy Engineering, Kyungpook National University, 80 Daehakro, Bukgu, Daegu 41566, Korea; [email protected] (J.K.); [email protected] (D.-E.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-53-950-5596 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 4 September 2020; Accepted: 6 October 2020; Published: 11 October 2020 Abstract: In this study, we examined the effects of cement fineness, SO3 content, an accelerating agent, and chemical admixtures mixed with unit weights of cement on concrete early strength using concrete mixtures. C24 (characteristic value of concrete, 24 MPa) was used in the experiment conducted. Ordinary Portland cement (OPC), high fineness and SO3 OPC (HFS_OPC), and Early Portland cement (EPC) were selected as the study materials. The unit weights of cement were set to OPC 330, 350, and 380. Further, a concrete mixture was prepared with a triethanolamine (TEA)-based chemical admixture to HFS. A raw material analysis was conducted, and the compressive strength, temperature history, and maturity (D h) were examined. Then, the vertical formwork removal time was evaluated · according to the criterion of each country. -

Components of Concrete Desirable Properties of Concrete

Components of Concrete Concrete is made up of two components, aggregates and paste. Aggregates are generally classified into two groups, fine and coarse, and occupy about 60 to 80 percent of the volume of concrete. The paste is composed of cement, water, and entrained air and ordinarily constitutes 20 to 40 percent of the total volume. In properly made concrete, the aggregate should consist of particles having adequate strength and weather resistance and should not contain materials having injurious effects. A well graded aggregate with low void content is desired for efficient use of paste. Each aggregate particle is completely coated with paste, and the space between the aggregate particles is completely filled with paste. The quality of the concrete is greatly dependent upon the quality of paste, which in turn, is dependent upon the ratio of water to cement content used, and the extent of curing. The cement and water combine chemically in a reaction, called hydration, which takes place very rapidly at first and then more and more slowly for a long period of time in favorable moisture conditions. More water is used in mixing concrete than is required for complete hydration of the cement. This is required to make the concrete plastic and more workable; however, as the paste is thinned with water, its quality is lowered, it has less strength, and it is less resistant to weather. For quality concrete, a proper proportion of water to cement is essential. Desirable Properties of Concrete Durability: Ability of hardened concrete to resist -

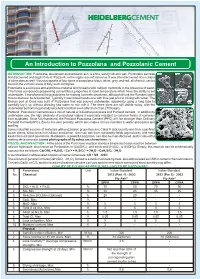

An Introduction to Pozzolana and Pozzolanic Cement

An Introduction to Pozzolana and Pozzolanic Cement INTRODUCTION: Pozzolana, also known as pozzolanic ash, is a fine, sandy volcanic ash. Pozzolanic ash was first discovered and dug in Italy at Pozzuoli , in the region around Vesuvius. It was later discovered at a number of other sites as well. Vitruvius speaks of four types of pozzolana: black, white, grey, and red, all of which can be found in the volcanic areas of Italy, such as Naples. Pozzolana is a siliceous and aluminous material which reacts with calcium hydroxide in the presence of water. This forms compounds possessing cementitious properties at room temperature which have the ability to set underwater. It transformed the possibilities for making concrete structures, although it took the Romans some time to discover its full potential. Typically it was mixed two-to-one with lime just prior to mixing with water. The Roman port at Cosa was built of Pozzolana that was poured underwater, apparently using a long tube to carefully lay it up without allowing sea water to mix with it. The three piers are still visible today, with the underwater portions in generally excellent condition even after more than 2100 years. Portland Pozzolanic Cements are a mix of natural or industrial pozzolans and Portland cement. In addition to underwater use, the high alkalinity of pozzolana makes it especially resistant to common forms of corrosion from sulphates. Once fully hardened, the Portland Pozzolana Cement (PPC) will be stronger than Ordinary Portland Cement(OPC), due to its lower porosity, which also makes it more resistant to water absorption and spalling. -

Vysoké Učení Technické V Brně Brno University of Technology

VYSOKÉ UČENÍ TECHNICKÉ V BRNĚ BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY FAKULTA STAVEBNÍ FACULTY OF CIVIL ENGINEERING ÚSTAV TECHNOLOGIE STAVEBNÍCH HMOT A DÍLCŮ INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OF BUILDING MATERIALS AND COMPONENTS VLIV VLASTNOSTÍ VSTUPNÍCH MATERIÁLŮ NA KVALITU ARCHITEKTONICKÝCH BETONŮ INFLUENCE OF INPUT MATERIALS FOR QUALITY ARCHITECTURAL CONCRETE DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCE DIPLOMA THESIS AUTOR PRÁCE Bc. Veronika Ondryášová AUTHOR VEDOUCÍ PRÁCE prof. Ing. RUDOLF HELA, CSc. SUPERVISOR BRNO 2018 1 2 3 Abstrakt Diplomová práce se zaměřuje na problematiku vlivu vlastností vstupních surovin pro výrobu kvalitních povrchů architektonických betonů. V úvodní části je popsána definice architektonického betonu a také výhody a nevýhody jeho realizace. V dalších kapitolách jsou uvedeny charakteristiky, dávkování či chemické složení vstupních materiálů. Kromě návrhu receptury je důležitým parametrem pro vytvoření kvalitního povrchu betonu zhutňování, precizní uložení do bednění a následné ošetřování povrchu. Popsány jsou také jednotlivé druhy architektonických betonů, jejich způsob vyrábění s uvedenými příklady na konkrétních realizovaných stavbách. V praktické části byly navrženy 4 receptury, kde se měnil druh nebo dávkování vstupních surovin. Při tvorbě receptur byl důraz kladen především na minimální segregaci čerstvého betonu a omezení vzniku pórů na povrchu ztvrdlého betonu. Klíčová slova Architektonický beton, vstupní suroviny, bednění, separační prostředky, cement, přísady, pigment. Abstract This diploma thesis focuses on the influence of properties of feedstocks for the production of quality surfaces of architectural concrete. The introductory part describes the definition of architectural concrete with the advantages and disadvantages of its implementation. In the following chapters, the characteristics, the dosage or the chemical composition of the input materials are given. Besides the design of the mixture, important parameters for the creation of a quality surface of concrete are compaction, precise placement in formwork and subsequent treatment of the surface. -

Early-Age Cracking in Concrete: Causes, Consequences, Remedial Measures, and Recommendations

applied sciences Review Early-Age Cracking in Concrete: Causes, Consequences, Remedial Measures, and Recommendations Md. Safiuddin 1,*, A. B. M. Amrul Kaish 2 , Chin-Ong Woon 3 and Sudharshan N. Raman 3,4,* 1 Angelo DelZotto School of Construction Management, George Brown College, 146 Kendal Avenue, Toronto, ON M5T 2T9, Canada 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Infrastructure University Kuala Lumpur, 43000 Kajang, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] 3 Centre for Innovative Architecture and Built Environment (SErAMBI), Faculty of Engineering and Built Environment, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 UKM Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] 4 Smart and Sustainable Township Research Centre (SUTRA), Faculty of Engineering and Built Environment, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 UKM Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia * Correspondence: msafi[email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (S.N.R.) Received: 15 July 2018; Accepted: 28 August 2018; Published: 25 September 2018 Abstract: Cracking is a common problem in concrete structures in real-life service conditions. In fact, crack-free concrete structures are very rare to find in real world. Concrete can undergo early-age cracking depending on the mix composition, exposure environment, hydration rate, and curing conditions. Understanding the causes and consequences of cracking thoroughly is essential for selecting proper measures to resolve the early-age cracking problem in concrete. This paper will help to identify the major causes and consequences of the early-age cracking in concrete. Also, this paper will be useful to adopt effective remedial measures for reducing or eliminating the early-age cracking problem in concrete. Different types of early-age crack, the factors affecting the initiation and growth of early-age cracks, the causes of early-age cracking, and the modeling of early-age cracking are discussed in this paper. -

How to Make Concrete More Sustainable Harald Justnes1

Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology Vol. 13, 147-154, March 2015 / Copyright © 2015 Japan Concrete Institute 147 Scientific paper How to Make Concrete More Sustainable Harald Justnes1 A selected paper of ICCS13, Tokyo 2013. Received 12 November 2013, accepted 16 February 2015 doi:10.3151/jact.13.147 Abstract Production of cement is ranking 3rd in causes of man-made carbon dioxide emissions world-wide. Thus, in order to make concrete more sustainable one may work along one or more of the following routes; 1) Replacing cement in con- crete with larger amounts of supplementary cementing materials (SCMs) than usual, 2) Replacing cement in concrete with combinations of SCMs leading to synergic reactions enhancing strength, 3) Producing leaner concrete with less cement per cubic meter utilizing plasticizers and 4) Making concrete with local aggregate susceptible to alkali silica reaction (ASR) by using cement replacements, thus avoiding long transport of non-reactive aggregate. 1 Introduction SCMs, also uncommon ones like calcined marl 2. Replacing cement in concrete with combinations of The cement industry world-wide is calculated to bring SCMs leading to synergic reactions enhancing about 5-8% of the total global anthropogenic carbon strength dioxide (CO2) emissions. The general estimate is about 3. Producing leaner concrete with less cement per cubic 1 tonne of CO2 emission per tonne clinker produced, if meter utilizing plasticizers. fossil fuel is used and no measures are taken to reduce it. 4. Making concrete with local aggregate susceptible to The 3rd rank is not because cement is such a bad mate- alkali silica reaction (ASR) by using cement re- rial with respect to CO2 emissions, but owing to the fact placements, thus avoiding long transport of non- that it is so widely used to construct the infrastructure reactive aggregate and buildings of modern society as we know it. -

Radiocarbon Dating of Mortars with a Pozzolana Aggregate Using the Cryo2sonic Protocol to Isolate the Binder

Radiocarbon Dating of Mortars with a Pozzolana Aggregate Using the Cryo2Sonic Protocol to Isolate the Binder Sara Nonni, Fabio Marzaioli, Silvano Mignardi, Isabella Passariello, Manuela Capano, Filippo Terrasi To cite this version: Sara Nonni, Fabio Marzaioli, Silvano Mignardi, Isabella Passariello, Manuela Capano, et al.. Ra- diocarbon Dating of Mortars with a Pozzolana Aggregate Using the Cryo2Sonic Protocol to Isolate the Binder. Radiocarbon, University of Arizona, 2017, 60 (2), pp.1 - 21. 10.1017/RDC.2017.116. hal-01683068 HAL Id: hal-01683068 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01683068 Submitted on 29 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Radiocarbon, 2017, p. 1–21. DOI:10.1017/RDC.2017.116 © 2017 by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona RADIOCARBON DATING OF MORTARS WITH A POZZOLANA AGGREGATE USING THE CRYO2SONIC PROTOCOL TO ISOLATE THE BINDER Sara Nonni1,2* • Fabio Marzaioli2,3 • Silvano Mignardi1 • Isabella Passariello2,3 • Manuela Capano4 • Filippo Terrasi2,3 1Department of Earth Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome, 00185 Rome, Italy. 2CIRCE (Centre for Isotopic Research on Cultural and Environmental Heritage) – INNOVA, 81020 San Nicola La Strada, Caserta, Italy.