Reflections of Medallion Ushak Carpets to European Painting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interiors and Interiority in Vermeer: Empiricism, Subjectivity, Modernism

ARTICLE Received 20 Feb 2017 | Accepted 11 May 2017 | Published 12 Jul 2017 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 OPEN Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism Benjamin Binstock1 ABSTRACT Johannes Vermeer may well be the foremost painter of interiors and interiority in the history of art, yet we have not necessarily understood his achievement in either domain, or their relation within his complex development. This essay explains how Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and used his family members as models, combining empiricism and subjectivity. Vermeer was exceptionally self-conscious and sophisticated about his artistic task, which we are still laboring to understand and articulate. He eschewed anecdotal narratives and presented his models as models in “studio” settings, in paintings about paintings, or art about art, a form of modernism. In contrast to the prevailing con- ception in scholarship of Dutch Golden Age paintings as providing didactic or moralizing messages for their pre-modern audiences, we glimpse in Vermeer’s paintings an anticipation of our own modern understanding of art. This article is published as part of a collection on interiorities. 1 School of History and Social Sciences, Cooper Union, New York, NY, USA Correspondence: (e-mail: [email protected]) PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:17068 | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 | www.palgrave-journals.com/palcomms 1 ARTICLE PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 ‘All the beautifully furnished rooms, carefully designed within his complex development. This essay explains how interiors, everything so controlled; There wasn’t any room Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and his for any real feelings between any of us’. -

Dutch Art, 17Th Century

Dutch Art, 17th century The Dutch Golden Age was a period in the history of the Netherlands, roughly spanning the 17th century, in which Dutch trade, science, military, and art were among the most acclaimed in the world. The first section is characterized by the Thirty Years' War, which ended in 1648. The Golden Age continued in peacetime during the Dutch Republic until the end of the century. The transition by the Netherlands to the foremost maritime and economic power in the world has been called the "Dutch Miracle" by historian K. W. Swart. Adriaen van Ostade (1610 – 1685) was a Dutch Golden Age painter of genre works. He and his brother were pupils of Frans Hals and like him, spent most of their lives in Haarlem. A01 The Painter in his Workshop 1633 A02 Resting Travelers 1671 David Teniers the Younger (1610 – 1690) was a Flemish painter, printmaker, draughtsman, miniaturist painter, staffage painter, copyist and art curator. He was an extremely versatile artist known for his prolific output. He was an innovator in a wide range of genres such as history, genre, landscape, portrait and still life. He is now best remembered as the leading Flemish genre painter of his day. Teniers is particularly known for developing the peasant genre, the tavern scene, pictures of collections and scenes with alchemists and physicians. A03 Peasant Wedding 1650 A04 Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in his gallery in Brussels Gerrit Dou (1613 – 1675), also known as Gerard and Douw or Dow, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, whose small, highly polished paintings are typical of the Leiden fijnschilders. -

Vermeer As Aporia: Indeterminacy, Divergent Narratives, and Ways of Seeing

Munn Scholars Awards Undergraduate Research 2020 Vermeer as Aporia: Indeterminacy, Divergent Narratives, and Ways of Seeing Iain MacKay Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/munn Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Vermeer as Aporia: Indeterminacy, Divergent Narratives, and Ways of Seeing Iain MacKay Senior Thesis Written in partial fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts in Art History April 23, 2020 Copyright 2020, Iain MacKay ABSTRACT Vermeer as Aporia: Indeterminacy, Divergent Narratives, and Ways of Seeing Iain MacKay Although Johannes Vermeer’s paintings have long been labelled “ambiguous” in the canon of Western Art History, this research aims to challenge the notion of ambiguity. By shifting the conception of Vermeer’s works from ambiguity to indeterminacy, divergent narratives emerge which inform a more complex understanding of Vermeer’s oeuvre. These divergent narratives understand Vermeer’s paintings as turning points in stories that extend beyond the canvas; moments where the possibilities of a situation diverge in different directions. Thus, a myriad of narratives might be contained in a single painting, all of which simultaneously have the possibility of existing, but not the actuality. This interpretation of Vermeer takes evidence from seventeenth-century ways of seeing and the iconographic messages suggested by the paintings within paintings that occur across Vermeer’s oeuvre. Here for the first time, an aporetic approach is utilized to explore how contradictions and paradoxes within a system serve to contribute to holistic meaning. By analyzing four of Vermeer’s paintings – The Concert, Woman Holding a Balance, The Music Lesson, and Lady Seated at a Virginal – through an aporetic lens, an alternative to ambiguity can be constructed using indeterminacy and divergent narratives that help explain compositional and iconographical choices. -

Antique Oriental Rugs Essential Reference Books

www.artpane.com Antique Oriental Rugs Essential Reference Books שטיחים עתיקים שגילם 08 שנים ומעלה הופכים להיות נדירים יותר ויותר. מרבית השטיחים המיוחדים והעתיקים שיוצרו בעבודת יד ובטכניקות אריגה וצביעה יחודיות בסוף המאה ה91- ובתחילת המאה ה08- באיזורי פרס, טורקמניסטאן ומרכז אסיה נעלמו מן השווקים. גם הידע וההבנה בשטיחים מהתקופה הזאת נעלמו מן השווקים. סוחרי השטיחים בני זמנינו עוסקים בעיקר ביבוא של שטיחים חדשים, לעיתים באיכות נמוכה, המיוצרים במזרח ומנסים לחקות את הדוגמאות והדגמים של העבר. מעטים מן העוסקים בשטיחים כיום מבינים במקורות השטיחים העתיקים, טכניקות האריגה והצביעה והדוגמאות המיוחדות המאפיינות את יצירות האמנות הללו. די נפוץ לשמוע דעות שונות, לעיתים סותרות, בקשר למקורו ולגילו של שטיח, הכל בהתאם לנקודת המבט והכדאיות של המומחה. שלושת הספרים המוצגים כאן הם נכס הכרחי בארגז הכלים של אספן שטיחים עתיקים מהמזרח שמנסה לאפיין את מקורו, גילו והרקע התרבותי של שטיח אספנות הנקרה בדרכו. *** Antique Oriental carpets and rugs has long been valued as works of art and fine examples are to be seen in museums and private collections throughout the world. These designs have been handled down from generation to generation of craftsmen, but antique carpets made by the traditional methods are getting rare. For the past hundred years, and possible longer, one of the treasures of collectors' art world has been the authentic handmade oriental carpet, imported from Turkey, Persia, central Asia or even occasionally from China. Further down in, you will find some rugs and carpets reference books, most of which are out of print, collectible items in a very good condition; you are invited to contact me and I will send you further information including full description of the book's condition, price and estimated shipping cost. -

2Bbb2c8a13987b0491d70b96f7

An Atlas of Rare & Familiar Colour THE HARVARD ART MUSEUMS’ FORBES PIGMENT COLLECTION Yoko Ono “If people want to make war they should make a colour war, and paint each others’ cities up in the night in pinks and greens.” Foreword p.6 Introduction p.12 Red p.28 Orange p.54 Yellow p.70 Green p.86 Blue p.108 Purple p.132 Brown p.150 Black p.162 White p.178 Metallic p.190 Appendix p.204 8 AN ATLAS OF RARE & FAMILIAR COLOUR FOREWORD 9 You can see Harvard University’s Forbes Pigment Collection from far below. It shimmers like an art display in its own right, facing in towards Foreword the glass central courtyard in Renzo Piano’s wonderful 2014 extension to the Harvard Art Museums. The collection seems, somehow, suspended within the sky. From the public galleries it is tantalising, almost intoxicating, to see the glass-fronted cases full of their bright bottles up there in the administra- tive area of the museum. The shelves are arranged mostly by hue; the blues are graded in ombre effect from deepest midnight to the fading in- digo of favourite jeans, with startling, pleasing juxtapositions of turquoise (flasks of lightest green malachite; summer sky-coloured copper carbon- ate and swimming pool verdigris) next to navy, next to something that was once blue and is now simply, chalk. A few feet along, the bright alizarin crimsons slake to brownish brazil wood upon one side, and blush to madder pink the other. This curious chromatic ordering makes the whole collection look like an installation exploring the very nature of painting. -

EDWARD DOLNICK for Lynn It Is in the Ability to Deceive Oneself That the Greatest Talent Is Shown

THE FORGER’S SPELL A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieths Century EDWARD DOLNICK For Lynn It is in the ability to deceive oneself that the greatest talent is shown. —Anatole France We have here a—I am inclined to say the—masterpiece of Johannes Vermeer. —Abraham Bredius CONTENTS Epigraph iii Preface ix Part One OCCUPIED HOLLAND 1 A Knock on the Door 3 2 Looted Art 6 3 The Outbreak of War 9 4 Quasimodo 14 5 The End of Forgery? 18 6 Forgery 101 22 7 Occupied Holland 26 8 The War Against the Jews 30 9 The Forger’s Challenge 33 10 Bargaining with Vultures 40 11 Van Meegeren’s Tears 44 Part Two HERMANN GOERING AND JOHANNES VERMEER 12 Hermann Goering 51 13 Adolf Hitler 55 vi con t e n t s 14 Chasing Vermeer 57 15 Goering’s Art Collection 62 16 Insights from a Forger 66 17 The Amiable Psychopath 77 18 Goering’s Prize 82 19 Vermeer 85 20 Johannes Vermeer, Superstar 88 21 A Ghost’s Fingerprints 93 Part Three THE SELLING OF CHRIST AT EMM AUS 22 Two Forged Vermeers 105 23 The Expert’s Eye 109 24 A Forger’s Lessons 115 25 Bredius 121 26 “Without Any Doubt!” 127 27 The Uncanny Valley 132 28 Betting the Farm 137 29 Lady and Gentleman at the Harpsichord 139 30 Dirk Hannema 145 31 The Choice 150 32 The Caravaggio Connection 163 33 In the Forger’s Studio 167 34 Christ at Emmaus 170 35 Underground Tremors 173 con t e n t s vii Photographic Insert 36 The Summer of 1937 179 37 The Lamb at the Bank 186 38 “Every Inch a Vermeer” 192 39 Two Weeks and Counting 198 40 Too Late! 201 41 The Last Hurdle 203 42 The Unveiling 207 -

Recording the Transformation of Urban Landscapes in Turkey: the Diaries Of

This article was downloaded by: [171.67.216.23] On: 24 February 2013, At: 15:45 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Studies in Travel Writing Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rstw20 Recording the transformation of urban landscapes in Turkey: the diaries of Kurt Erdmann and Ernst Diez Patricia Blessing Version of record first published: 27 Sep 2012. To cite this article: Patricia Blessing (2012): Recording the transformation of urban landscapes in Turkey: the diaries of Kurt Erdmann and Ernst Diez, Studies in Travel Writing, 16:4, 415-425 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13645145.2012.723862 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Art and New Media: Vermeer's Work Under Different Semiotic Systems

Vieira Art and New Media: Vermeer’s Work under Different Semiotic Systems Vieira 2 Miriam de Paiva Vieira Art and New Media: Vermeer’s Work under Different Semiotic Systems Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of "Mestre em Letras: Estudos Literários". Area: Literatures in English Line of Research: Literature and other semiotic systems Thesis Advisor: Prof. Dra. Thaïs Flores Nogueira Diniz Belo Horizonte Faculdade de Letras Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais 2007 Vieira, Miriam de Paiva. V658a Art and new media [manuscrito] : Vermeer’s work under different semiotic systems / Miriam de Paiva Vieira. – 2007. 116 f., enc. : il. color., p&b, tab. Orientadora : Thaïs Flores Nogueira Diniz. Área de concentração: Literaturas de Expressão Inglesa. Linha de Pesquisa: Literatura e outros Sistemas Semióticos. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Letras. Bibliografia : f. 110-116. 1. Vermeer, Johannes, 1632-1675 – Crítica e interpretação – Teses. 2. Arte e literatura – Teses. 3. Adaptações para o cinema – Teses. 4. Semiótica e artes – Teses. 5. Semiótica e literatura – Teses. 6. Intermedialidade – Teses. 7. Transtextualidade – Teses. I. Diniz, Thaïs Flores Nogueira. II. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Faculdade de Letras. III. Título. CDD : 809.93357 Vieira 3 I dedicate this work to the new reason of my life: Débora. Vieira 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my dear nephew Guilherme and all the late snacks brainstorming over the kitchen’s table. To my good friend James and his thoughtful revisions. To my sister Maria Teresa for making me laugh at the most difficult times. To my colleague, and now good friend, Patrícia Lane for all the sharing. -

«The Carpet Paradigm» L’Impatto Del Tappeto Orientale Nell’Arte Contemporanea

Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Storia delle Arti e Conservazione dei Beni Artistici Tesi di Laurea «The Carpet Paradigm» L’impatto del tappeto orientale nell’arte contemporanea Relatore Prof. Giuseppe Barbieri Correlatrice Prof.ssa Sara Mondini Laureanda Ludovica Matarozzo Matricola 871929 Anno accademico 2018/2019 Indice Introduzione ......................................................................................................................... 2 1 Il tappeto, trama di segni ........................................................................................... 11 1.1 Il tappeto come rivoluzione decorativa ................................................................. 12 1.2 “Proprietà vettoriali” del tappeto nell’arte occidentale ......................................... 14 1.3 Una nuova opera d’arte ......................................................................................... 18 1.4 Produrre, calpestare, consumare il tappeto ........................................................... 26 2 Il tappeto orientale entra nell’arte contemporanea ................................................ 32 2.1 Artista VS Tessitrici: riscrivere confini identitari .................................................. 38 2.2 Cancellare la materia, aggiungere strati di significato .......................................... 52 2.3 (De)strutturare l’ “Oriente” ................................................................................... 63 2.3.1 Il tappeto volante può ancora volare? ........................................................... -

Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World

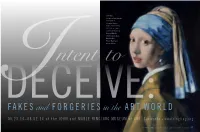

John Myatt, Girl with a Pearl Earring, in the style of Johannes Vermeer (Dutch, 1632-1675), 2012, oil on canvas. Courtesy of Graham & Margaret Wright, Stratford Upon Avon, Warwickshire. Photo: Washington Green Fine Art ntent to IDECEIVE: FAKES and FORGERIES in the ART WORLD 05.23.14–08.02.14 at the JOHN and MABLE RINGLING MUSEUM of ART, Sarasota • www.ringling.org O N V IEW M AGAZINE . C om • A PRIL /J UNE 2 0 1 4 81 Intent to Deceive PROVOCATIVE NEW EXHIBIT about art forgery will have its Florida debut at The John and Mable Ringling Muse- um of Art in Sarasota. Intent to Deceive: Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World spotlights some of the world’s most notorious con artists, illuminating their dubi- ous legacies, and examining how their talents, charm, and audacity beguiled and assaulted the art world for much of the 20th century through the present day. The exhibition, which is organized by International Arts & Artists of Washington, DC, and curated by Colette Loll, will be on view from May 23 through August 8, 2014. Several ingenious forgers are landing one in jail. profiled in this ground-breaking The exhibit is divided into exhibition representing some sections that examine each of the most infamous scandals forger’s career. Included in of the last century. Han van each profile are original works, AMeegeren, Elmyr de Hory and personal effects and ephem- Eric Hebborn all shook the art era, photographs, film clips, world with their exploits, gar- and representations of the John Myatt, Odalisque, nering each of them worldwide material and techniques used limited edition print; notoriety but an untimely death. -

TƏSVİRİ VƏ DEKORATİV – TƏTBİQİ SƏNƏT MƏSƏLƏLƏRİ Xüsusi Buraxılış

AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASI MƏDƏNİYYƏT NAZİRLİYİ AZƏRBAYCAN XALÇA MUZEYİ TƏSVİRİ VƏ DEKORATİV – TƏTBİQİ SƏNƏT MƏSƏLƏLƏRİ Xüsusi buraxılış AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASI MƏDƏNİYYƏT VƏ TURİZM NAZİRLİYİ AZƏRBAYCAN XALÇA MUZEYİ Azərbaycan Respublikası Mədəniyyət və Turizm Nazirliyi, Yunus Əmrə İnstitutunun Bakı Türk Mədəniyyət Mərkəzi, Azərbaycan Xalça Muzeyinin birgə təşkilatçılığı ilə “Ortaq qaynaqdan çeşidli yollar” mövzusunda II Beynəlxalq “Türk dünyasının ortaq dili – naxışlar” simpoziumunun materialları 22-24 may 2017-ci il Bakı - 2018 Elmi heyət: Simpoziumun kuratoru Şirin Məlikova, Azərbaycan Xalça Muzeyinin direktoru, sənətşünaslıq üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru, dosent, ICOM-Azərbaycan Milli Komitəsinin sədri Bekir Deniz, sənətşünaslıq üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor (Ardahan Universiteti) Elmira Gül, sənətşünaslıq üzrə elmlər doktoru (Özbəkistan Elmlər Akademiyasının İncəsənət İnstitutu) Yaşar Çoruhlu, sənətşünaslıq üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor (Memar Sinan Gözəl Sənətlər Universiteti) Nalan Türkmen, sənətşünaslıq üzrə elmlər doktoru, dosent (Marmara Universiteti) Hatice Feriha Akpınarlı, sənətşünaslıq üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor (Qazi Universiteti) Nizami Cəfərov, filalogiya üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor, AMEA-nın müxbir üzvü (Atatürk Mərkəzinin müdiri) Kubra Əliyeva, sənətşünaslıq üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor (AMEA Memarlıq və İncəsənət İnstitutu) Sevil Sadıxova, sənətşünaslıq üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor (Azərbaycan Dövlət Rəssamlıq Akademiyası) Toğrul Əfəndiyev, sənətşünaslıq üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru (Azərbaycan Milli İncəsənət Muzeyi) Xədicə -

Id Title Publisher Year Subtitle Dep Isbn1 Isbn2

ID TITLE PUBLISHER YEAR SUBTITLE DEP ISBN1 ISBN2 BOOK NR AUTHOR 1 The women's warpath ucla fowler museum of 1996 Iban ritual fabrics from borneo 15 0-930741-50-1 0-930741-51-x SEA0001 Traude Gavin cultural history 2 Textile traditions of Los Angeles county 1977 15 0-87587-083-x SEA0002 Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Indonesia museum of art 3 Indonesische Textilien Deutsches Textilmuseum 1984 Wege zu Göttern und Ahnen 15 3-923158-05-X SEA0003 Brigitte Khan Majlis Krefeld 4 Walk in splendor ucla fowler museum of 1999 ceremonial dress and the 15 0-930741-72-2 0-930741-73-0 SEA0004 T.Abdullah cultural history Minangkabau 5 Geometrie d'Oriente sillabe, Livorno 1999 Stefano Bardini e il tappeto 5 88 -8347- 010-9 GEN0029 Alberto Boralevi Oriental Geometries antico Stefano Bardini and the Antique Carpet 6 Her-ontdekking van Lamandart 1994 17 90-5276-009-8 90-5276-008-X SNA0001 Brommer,De Precolumbiaans Textiel Bolle,Hughes,Pollet,Sorbe r,Verhecken 7 Eeuwen van weven Nederlands 1992 Bij de Hopi- en Navajo- indianen 17 90-7096217-9 SNA0002 Helena Gelijns, Fred van Textielmuseum Tilburg Oss 8 Bolivian Indian Textiles dover publications, inc. 1981 Traditional Designs and 17 0-486-24118-1 SNA0003 Tamara E.Wasserman, Costumes Jonathan S.Hill 9 3000 jaar weven in de Andes Gemeentemuseum 1988 textiel uit Peru en Bolivia 17 90 68322 14 1 SNA0004 Brommer, Lugtigheid, Helmond Roelofs, Mook-Andreae 10 Coptic Textiles The friends of the Benaki 1971 22 Mag0019 Benaki Museum Museum,Athens 11 Coptic Fabrics Adam Biro 1990 14 2-87660-084-6 CPC0002 Marie Helene Rutschowscaya